|

|

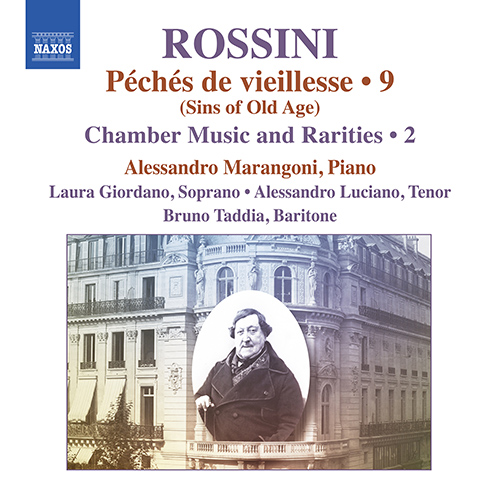

1 CD -

8.573864 - (p) & (c) 2018

|

|

| PÉCHÉS

DE VIEILLESSE - Volume 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gioachino ROSSINI

(1791-1868) |

Péchés

de vieillesse - Volume I "Album

italiano"

|

|

|

|

|

-

No. 3 - Tirana alla spagnola

(rossinizzata), per soprano e pianoforte

|

|

6' 36" |

1 |

|

- No. 5 - La

fioraja fiorentina, per soprano

e pianoforte

|

|

4' 24" |

2 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume XI "Miscellanée de musique

vocale" |

|

|

|

|

-

No. 7 - Arietta all'antica, dedotta dal

"O salutaris Hostia", per soprano e e

pianoforte (1857) |

|

2' 16" |

3 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume II "Album français" |

|

|

|

|

-

No. 3 - La grande coquette (Ariette

Pompadour), per soprano e pianoforte

(1862)

|

|

4' 56" |

4 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume III "Morceaux

réservés" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 8 - Au chevet d'un

mourant (Élégie), per soprano e

pianoforte |

|

6' 30" |

5 |

|

Mi lagnerò tacendo,

per soprano e pianoforte

|

|

9' 49" |

6 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume XI "Miscellanée de musique

vocale" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 3 - Amour sans

espoir (Tirana à l'espagnole

rossinizée), per soprano e pianoforte

|

|

6' 46" |

7 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume I "Album italiano" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 2 - La lontananza,

per tenore e pianoforte |

|

5' 07" |

8 |

|

- No. 11 - Il fanciullo

smarrito, per tenore e pianoforte

|

|

3' 34" |

9 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume III "Morceaux

réservés" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 2 . L'esule, per

tenore e pianoforte

|

|

4' 07" |

10 |

|

- No. 9 - Le Sylvain

(Romance), per tenore e pianoforte |

|

8' 26" |

11 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume II "Album français" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 2 - Roméo, per

tenore e pianoforte |

|

4' 41" |

12 |

|

Allegretto moderato,

per pianoforte (1862) |

|

0' 18" |

13 |

|

Allegretto "del

pantelegrafo", per pianoforte

(1860) |

|

0' 15" |

14 |

|

Allegretto - Un rien,

per pianoforte (1860) |

|

0' 18" |

15 |

|

Vivace, per

pianoforte (1846) |

|

0' 14" |

16 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume I "Album italiano" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 4 - L'ultimo

ricordo, per baritono e pianoforte |

|

3' 57" |

17 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume II "Album français" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 8 - Le Lazzarone.

Chansonette de cabaret, per baritono e

pianoforte |

|

3' 26" |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

Alessandro

MARANGONI, pianoforte

Laura GIORDANO, soprano

(tracks 1-7)

Alessandro LUCIANO,

tenore (tracks 8-12)

Bruno TADDIA, baritono

(tracks 13-18)

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Baroque

Hall, Ivrea, Torino (Italia) - Studio

SMC Records: 2017

- 18 aprile (tracks 1,7)

- 24 maggio (tracks 8-12)

Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino,

Firenze (Italia) - 2017

- 1 dicembre (tracks 13-18) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio

|

|

studio |

|

|

Producers |

|

Renato

Campajola & Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Renato Campajola

& Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Editors |

|

Renato

Campajola & Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Special

thanks |

|

Reto

Müller & Sergio Ragni |

|

|

Edizione

CD |

|

NAXOS |

8.573864 | (1 CD) | durata 67' 59" |

(p) & (c) 2018 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

When,

in 1867, Rossini began

organising the compositions he

had been accumulating over the

previous ten years or so, which

he termed Péchés de

vieillesse (‘Sins of Old

Age’; the form of the titles

given here preserves Rossini’s

orthography), into albums, he

was motivated not just by

tidiness, but also by a

clear-cut objective relating to

their publication. He intended

his wife, Olympe, to be able to

sell the pieces to publishers on

the most advantageous terms

possible after he had died. The

albums contain a varied

selection of pieces—the classic

dozen in most instances—in

groupings based on content,

musical criteria and the forces

required. This can be seen most

clearly in the first three vocal

albums, Album Italiano

(Volume I), Album français

(Volume II) and Morceaux

réservés (Volume III), all

of which feature a balanced

blend of solo and ensemble

pieces arranged in a broadly

symmetrical fashion. It is also

possible to make out patterns in

the keys or the ‘stories’ that

have been set to music.

After Volumes IV to X, which are

devoted to piano and other

instrumental music, comes a Miscelanée

de Musique Vocale (Volume

XI). Although the title betrays

a less coherent collection of

ten ‘surplus’ pieces, here too

it is possible to make out a

common thread in the domestic

and religious subject-matter. In

this anthology, Rossini’s

autographs are presented just as

Olympe handed them over to his

home-town of Pesaro, as dictated

by his last will and testament.

(Today, they are curated there

by the Fondazione Rossini.)

Rossini had copies made of all

the pieces, checking and, where

necessary, correcting and

completing them before signing

them. In particular, he also

added metronome markings, which

he never included in his own

autographs unless his publisher

requested them—a clear

indication that it was his

intention to create accurate,

printready master copies that

his wife would only need to sell

on, without having to part with

the autographs. This is what she

did, and a significant number of

such authenticated manuscripts

survived and were acquired in

1996 by Harvard University’s

Houghton Library.

While the albums in their

original form certainly have a raison

d’être and each can

deliver a varied concert

programme, Rossini’s salon

practice was to take his cue

from the artists available, each

of whom would present pieces

that were suitable for them at

his Saturday soirées. Modern

studio recordings have to be

organised rationally, taking

account of album playing times.

The present recording brings

together the solo numbers for

soprano, tenor and baritone from

the three albums discussed above

and adds a couple of miniature

gems.

In his youth, when he was

writing operas, Rossini had only

ever composed when he had a

definite end in mind and a

libretto. In his old age, he

also developed musical ideas

when he didn’t have a poem

available. When spontaneously

inscribing album leaves, he

always drew on the words of an

aria from Metastasio’s Siroe,

“Mi lagnerò tacendo / della mia

sorte amara …”—‘I shall mourn in

silence my unhappy fate…’. (This

disc includes the premiere

recording of an undated

example [6] .) He

often used the same lines,

stripped of any semantic

connotation, to provide a

syllabic underlay for more

demanding compositions—a tirana,

or Andalusian dancesong, for

example: Tirana alla

Spagnola (Rossinizzata)

(‘Tirana in the Spanish Manner,

given the Rossini treatment’, Péchés

de vieillesse, Volume I, No. 3

[1] ). Sometimes he would

ask one of his house poets to

write some suitable verse for

music that had been composed in

this manner. In this case, the

result was Amour sans espoir

(Tirana all’Espagnole

Rossinizée) to a text by

Émilien Pacini (‘Love Without

Hope [a tirana in the Spanish

manner given the Rossini

treatment]’, Volume XI No. 3

[7] ). With a few

alterations to the tune and

accompaniment, of course.

Pacini also wrote some fairly

free verses to fit the music for

La grande coquette (Ariette

Pompadour) (‘The Great

Coquette [Pompadour Arietta]’, Volume

II, No. 3 [4]

), which he dated ‘29th January

1862’. La Fioraja Fiorentina

(‘The Florentine Flower Girl’, Volume

I, No. 5 [2]

), one of the many ‘alms’ songs

in Péchés de vieillesse,

was also composed to

Metastasio’s text, and its main

tune can already be found in

album leaves dating from 1848

and 1852. In this instance it

was probably Giuseppe Torre who

wrote the new text.

Other pieces made the reverse

journey. The Arietta

all’antica, dedotta dal ‘O

Salutaris Ostia’ (‘Arietta

in the antique manner, derived

from “O salutaris hostia”’, Volume

XI, No. 7 [3]

) is a revised version of an a

cappella quartet that Rossini

had composed for the periodical

La Maîtrise in 1857.

Finally, there are numerous

pieces that represent direct

settings of new poems. Au

chevet d’un Mourant (Elégie)

(‘At the Bedside of a Dying Man

[Elegy]’, Volume III, No. 8

[5] ) sets lines by

Émilien Pacini without any

intermediate stages; Rossini

dedicated them to Pacini’s

sister, Madame de Lafitte. The

brother and sister were among

seven children whose father, the

publisher Antonio Pacini, died

on 10 March 1866. Antonio had

been one of the foremost

publishers of works by Rossini

as early as the 1820s and had

made a remarkable assessment of

Rossini’s late works as his

‘most illustrious period. What

he composes daily are a series

of masterpieces that seems as

though it will never end.’

Interestingly, none of the

pieces for tenor and baritone

seem to have been based on the

Metastasio text. All were

probably directly inspired by

the final poems. When Rossini

had been composing operas, male

voices had only been divided

into tenors and basses.

‘Baritone’ was a concept that

only gained currency around the

middle of the 19th century,

hence Rossini’s occasional

flippant labelling of this

voice-category as ‘baryton

moderne’. Le Lazzarone.

Chansonette de Cabaret

(The Idler. A Little Cabaret

Song’) was only assigned to the

baritone as a second step,

whilst L’ultimo Ricordo

(‘The Final Keepsake’) remained

earmarked simply for ‘Canto’

(voice). Rossini clearly did not

wish to describe himself as a

baritone, although, as a fine

exponent of his Figaro aria,

that was probably exactly his

vocal tessitura. In this piece (Volume

I, No. 4 [17]

), by replacing the name Elvira

with Olimpia, he applies an old

poem by Giovanni Redaelli about

a dying husband to himself. In Le

Lazzarone (Volume II,

No. 8 [18]

), to words by Émilien Pacini

(whose father was Neapolitan by

birth), on the other hand, he

was indulging his youthful

memories of Naples (about which

he had written in 1815:

‘Everything is beautiful,

everything astounds me’).

The tenor voice is given genre

songs and character pieces. In La

Lontananza (‘Distance’, Volume

I, No. 2 [8]

), Giuseppe Torre, a Genoese

librettist and poet, wrote a

loving greeting from a far-away

husband, and in L’Esule

(‘The Exile’, Volume III,

No. 2 [10] )

described the homesickness of an

émigré. Although Rossini

rejected seditious ideas and

kept out of politics, as early

as the 1830s he had had contact

in Paris with many of his

compatriots who had to leave

Italy after the failed

independence movements of 1831,

and as this song demonstrates,

he was well able to understand

their feelings. Rossini gave

Torre separate copies of both

the pieces on 20 August 1858.

The Roman archaeologist

Alessandro Castellani was

another exile. In 1861 he showed

Rossini Il Fanciullo

Smarrito (‘The Missing

Child’), a song for which he had

written both words and music,

about the search for a little

boy and a bell to summon

attention. Rossini’s reaction

was: ‘My dear boy, devote

yourself to archaeology and

leave composition to me.’ He

dedicated his own setting (Volume

I, No. 11 [9]

), which imitates the

characteristic tinkling of the

bell, to Castellani, who

published it in 1881, commending

it to ‘tenorini di grazie’.

Émilien Pacini was also the poet

behind Roméo (Volume II, No.

2 [12] ), a

despairing lament on the part of

Romeo over the presumed death of

his Juliet (which Rossini also

pressed into service as an Allegro

agitato for cello and

piano), and the quirky Le

Sylvain (‘The Wood-

Sprite’, Volume III, No. 9

[11] ), about a Silenus

or faun whom the beautiful

nymphs avoid because of his

savage ugliness.

Both before and during the

period of his ‘Sins of Old Age’,

Rossini also noted down numerous

pieces that were too short to be

included in his ‘publication

project’. Most are album leaves

which, because of their nature

as works dedicated to

individuals, neither remained in

his possession nor made their

way to Pesaro with the albums,

instead being scattered around

in archives and private

collections all over the world.

It is possible that more could

come to light at any time. Often

the lack of a specific

dedication means that the

recipient of the album leaf can

no longer be determined. The

ten-bar Vivace [16]

dated ‘Bologna, 19th March

1846’, had already formed part

of a longer composition which

Rossini had dedicated to one

Marietta Lombardi on 1 January

1846. An Allegretto moderato,

dated ‘G. Rossini, Paris,

1862’ [13]

is another of his favourite

pieces for album leaves and

visiting cards, as is the Allegretto—Un

rien (‘A Trifle’ [15]

) with its typical upwards glissando,

dated ‘Paris, 12th Dec. 1860, G.

Rossini’. Another Allegretto

[14] had a specific

purpose: it was to be sent by

telegraph from Paris to Amiens.

At the foot of the work are the

words ‘For G. Caselli | G.

Rossini | Paris, 22nd January

1860’, and underneath the

recipient added: ‘Autograph by

Gioacchino Rossini, cabled from

Paris to Amiens | G. Caselli’.

It was the first transmission of

a ‘fax’ using the

‘pantélégraphe’, a device

invented by Giovanni Caselli

that used telegraphy to transmit

documents, and was an effective

piece of publicity. Contrary to

what might be expected of him,

Rossini’s gesture demonstrates

that he was in no way averse to

technological innovation!

Reto Müller

Translation: Sue

Baxter

|

|