|

|

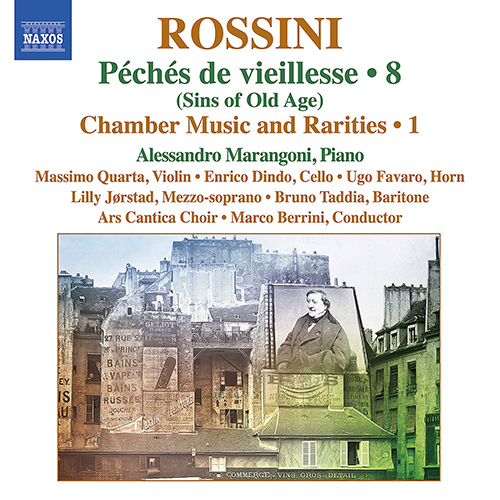

1 CD -

8.573822 - (p) & (c) 2018

|

|

| PÉCHÉS

DE VIEILLESSE - Volume 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gioachino ROSSINI

(1791-1868) |

Péchés

de vieillesse - Volume IX "Album pour

piano, violon, violoncello, harmonium

et cor"

|

|

|

|

|

-

No. 4 - Un mot à Paganini (Élégie), per

violino e pianoforte

|

|

9' 50" |

1 |

|

Allegretto, per

violino e pianoforte (1853)

|

|

0' 22" |

2 |

|

Tema,

per violino e pianoforte (1845) |

|

1' 51" |

3 |

|

Un

mot pour bass et piano, per

violoncello e pianoforte (1858)

|

|

1' 17" |

4 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume XIV "Altri

Péchés de vieillesse" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 12 - Allegro

agitato, ricostruzione per violoncello e

pianoforte (1867) |

|

4' 01" |

5 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume IX "Album pour piano, violon,

violoncello, harmonium et cor" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 10 - Une larme,

Thème et Variations, per violoncello e

pianoforte (1861)

|

|

9' 49" |

6 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume VIII "Album de chateau" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 9 - Tarantelle pur

sang (avec traversée de la

procession), per coro, harmonium,

clochette e pianoforte (1865)

|

|

11' 05" |

7 |

|

Thème et Variations,

in mi minore per pianoforte |

|

4' 25" |

8 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume IX "Album pour piano, violon,

violoncello, harmonium et cor" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 8 - Prélude, Thème

et Variations, per corno e pianoforte

(1857)

|

|

9' 35" |

9-11 |

|

Valz, per

pianoforte (1841) |

|

1' 27" |

12 |

|

Ritournelle pour

l'Adagio du Trio d'Attila, per

pianoforte (1865) |

|

0' 20" |

13 |

|

Marlbrough s'en

va-t-en guerre, per pianoforte

(1864) |

|

0' 49" |

14 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume XIV "Altri

Péchés de vieillesse" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 14 - L'ultimo

pensiero. Un rien, per baritono e

pianoforte (1865) |

|

1' 54" |

15 |

|

- No. 10 - Metastasio.

Pour album, per baritono e pianoforte |

|

0' 30" |

16 |

|

Petit souvenir,

per pianoforte (1843) |

|

4' 11" |

17 |

|

Péchés de vieillesse

- Volume XI "Miscellanée de musique

vocale" |

|

|

|

|

- No. 10 - Giovanna

d'Arco, per mezzo-soprano e pianoforte |

|

16' 57" |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

Alessandro

MARANGONI, pianoforte

(tracks 1-18) & Harmonium

(track 7)

Massimo QUARTA, violino

(tracks 1-3)

Enrico DINDO, violoncello

(tracks 4-6)

Ugo FAVARO, corno (tracks

9-11)

Lilly JØRSTAD,

mezzo-soprano (track 18)

Bruno TADDIA, baritono

(tracks 15-16)

ARS CANTICA CHOIR / Marco

BERRINI, direttore (track

7)

Marco BERRINI,

clochette (track 7)

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Baroque

Hall, Ivrea, Torino (Italia) - Studio

SMC Records: 2017

- 27 marzo (tracks 7,9-11)

- 28 marzo (tracks 8,12-14,17)

- 18 aprile (tracks 15-16)

- 8 luglio (tracks 1-3)

- 25 luglio (track 18)

- 25 settembre (tracks 4-6) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio

|

|

studio |

|

|

Producers |

|

Renato

Campajola & Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Renato Campajola

& Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Editors |

|

Renato

Campajola & Mario Bertodo |

|

|

Special

thanks |

|

Reto

Müller & Sergio Ragni |

|

|

Edizione

CD |

|

NAXOS |

8.573822 | (1 CD) | durata 79' 21" |

(p) & (c) 2018 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The

date generally accepted as

marking the beginning of

Rossini’s miraculous return to

regular composition is 14 April

1857, when he dedicated the Musique

anodine to his wife

Olympe. However, this should not

blind us to the fact that the

origins of this ‘new’

compositional phase, which he

himself described as his Péchés

de vieillesse (‘Sins of

Old Age’), lay much further

back, with some aspects dating

from the period when he was

still working as an opera

composer (1810–29). The Soirées

musicales (published in

1835) anticipate the vocal

compositions of the Péchés

de vieillesse, from which

they are stylistically almost

indistinguishable, and during

the period from 1835 to 1857

Rossini wrote a plethora of

short compositions, mostly album

leaves, which also foreshadow

the Péchés de vieillesse.

Moreover, the collection of Péchés

de vieillesse itself forms

less of an organic whole than it

initially appears to. Alongside

those sorted into the albums

held by the Fondazione Rossini

in Pesaro (for which there is a

handwritten outline, held by the

Fonds Michotte in Brussels),

there are many other ‘Sins of

Old Age’ which were not

included, either because they

were surplus to requirements, or

because they represented

preliminary sketches or

variants, or had been published

without the composer’s

permission. Rossini left his

autographs to his home town of

Pesaro, stipulating that his

wife should have unrestricted

rights of use over them for the

rest of her life. Rossini’s

decision not to publish his Péchés

de vieillesse during his

lifetime thus appears to have

been based on commercial

considerations, and Olympe did

in fact try to get the best

price she could for selling the

rights to the unpublished works.

The pieces recorded here give an

overview of the diversity in

their origins. (The form of the

titles preserves Rossini’s

orthography.)

[1] ‘Allow me to

recommend you write the sonata

based on the Romance from Otello

and entitled “Le Souvenir di

Rossini a Paganini”’, Niccolò

Paganini (1782–1840) urged

Rossini in the 1830s, when the

two old friends often met in

Paris. As far as we are aware,

no such piece was ever composed,

and Rossini, perhaps remembering

his old promise, probably penned

Un mot à Paganini (Élégie)

many years after ‘the Devil’s

violinist’ had died.

[2] The short Allegretto

is a really catchy tune—one of

those ‘ideas that go round and

round in your head’, as Rossini

once put it, and which he used

countless times, including on

small visiting cards which he

distributed in 1856 in Bad

Kissingen. The motif eventually

found its way into the Prélude

in Musique anodine.

Rossini dedicated the version

for violin with piano

accompaniment to the singer

Adelaide Borghi-Mamo (1826–1901)

on 15 December 1853. A beautiful

lithograph of her published in

Paris in the Album du Grand

monde, along with a

facsimile of the piece,

describes it as an impromptu. A

copy was also printed in The

Illustrated London News of

6 January 1855.

[3] Among the students at

the Liceo Musicale in Bologna,

where Rossini was honorary

director from 1839 to 1848, was

the gifted violinist Giovacchino

Giovacchini (1825–1906). Rossini

wrote a Tema for him,

dedicating it ‘To Giovacchini |

G. Rossini | Bologna, 12th April

1845’. The two-page autograph

manuscript is housed at the

conservatory in Florence, while

the Fonds Michotte in Brussels

holds a single-sided autograph

copy that lacks the title and

dedication, as well as

Giovacchini’s own introduction

to and variations on the theme

that had been dedicated to him.

[4] Rossini met the

Belgian cellist François Servais

(1807–1866) in Paris and was so

taken with his playing that, on

impulse, he made him a present

of Un mot pour basse et

piano. (Rossini had

studied cello when he was at the

Liceo Musicale.) The autograph,

which bears a dedication ‘to

Servais | Rossini | Paris, 20th

March 1858’ was recently

discovered in a private

collection in Belgium. Servais

copied the cello part onto a

separate sheet of paper,

indicating the point where he

lacked a contrasting theme that

would enable him to compose

variations on the piece. Rossini

added another eight bars to this

sheet. The piece is recorded

here in this latter, completed

form, first published in 2016 in

La Gazzetta, the journal

of the German Rossini Society.

[6] Rossini stayed in

contact with Servais and was

soon calling him the ‘Paganini

of the cello’. On 23 March 1861,

Servais performed Une larme,

Thème et Variations at

Rossini’s salon, having learned

it in just two days. Rossini had

originally written a 33-bar

piece in memory of the late

cellist Michael Wielhorski

(1788–1856). Now, for Servais

(or, initially, for the Italian

cellist Gaetano Braga), he

prefaced it with a 14-bar piano

introduction and added a set of

variations culminating in a

virtuosic ensemble for the two

instruments. The result was a

‘cello concerto’ in miniature

with sections marked Andantino

– Allegro moderato – Meno

mosso – Allegro moderato –

Andantino – Allegro brillante.

[5] The Meno mosso

section of Une larme

(bars 65–88) also crops up in

the central section of the Allegro

agitato, for which only

the cello part has been

preserved in Pesaro. The nature

of the piano part that doubtless

would have belonged to it can be

deduced from Une larme

and the mélodie Roméo

from the Album Français

of the Péchés de vieillesse.

This is probably the form in

which the piece was played at a

soirée in the spring of 1867,

when Gaetano Braga, for whom it

may possibly have been written,

was accompanied at the piano by

Rossini himself.

[7] Rossini placed the Tarantelle

pur sang (avec traversée de la

procession) in the Album

de Château, an album

devoted entirely to piano

pieces, where the processional

chorale (of 51 bars) is for

piano solo; all attempts to find

the ‘Chorus, harmonium, bell at

the end, ad libitum’

indicated in the manuscript have

so far been in vain. However, in

Brussels there is a complete,

clean transcript in which the

processional is written out for

chorus (SATB) with harmonium

accompaniment. The verses, which

invoke San Gennaro, the patron

saint of Naples, before the

Virgin, are somewhat clumsy and

may have been penned by Rossini

himself. The piece was performed

at least twice in this form at

soirées in Rossini’s home (on 31

March 1865 and 17 April 1866).

[8] Among the Péchés

de vieillesse in Pesaro

which were not assigned to an

album, Alessandro Marangoni

discovered the hitherto

uncatalogued Thème et

Variations. Writing in his

book I Péchés de vieillesse

di Gioachino Rossini

(Naples, 2015), he says: ‘It is

clear from the manuscript that

the author initially only noted

down the theme, in E minor,

possibly just jotting it down on

a sheet of paper. The words et variations

have been added to the title …

furthermore, the signature after

the final bar of the theme has

been erased so as to continue

with the variations.’ The piece,

which is both technically

demanding and harmonically and

dynamically sophisticated,

displays other amendments

reminiscent of those typically

found in Rossini’s final drafts.

It looks almost as though he

himself misfiled the

piece—otherwise his failure to

include this polished

composition in any of the albums

is difficult to explain.

[9]–[11] Like the elegy Un

mot à Paganini, Rossini

placed the autograph manuscript

of Prélude, Thème et

Variations for horn and

piano in the ninth album of his

Péchés de vieillesse. The

Prélude shares the other

piece’s elegiac tone, which is

particularly well suited to the

sonority of the horn. It is

simply dedicated ‘to Vivier, G.

Rossini’. The Fondazione Rossini

holds another autograph copy of

the same piece which has a

complete dedication: ‘To the

charming Vivier. A small token

of my friendship, from Gioachino

Rossini. Paris, 11th May 1857’.

It thus dates from the time,

just a few months after his

visit to the health resorts of

Wildbad und Bad Kissingen, when

Rossini started composing

regularly again. Eugène Vivier

(1817–1900) was considered the

most outstanding horn player of

his day. Rossini already knew

him from his brief stay in Paris

in 1843, when Adolphe Adam had

introduced him with the words:

‘This is a horn that can sing

and play the violin’. Rossini’s

variations certainly prove

Vivier’s virtuosity. The

composer’s biographer Radiciotti

describes the piece as a

‘Rondeau fantastique in two

parts’. Rossini’s love of the

horn, which is also given

frequent solo parts in his

operas, is certainly also

attributable to his father

having been a horn player and

Rossini thus having been

familiar with the instrument

from infancy.

[12] On 12 December 1841

a pretty Valz – Composto par

G. Rossini was published

in Keepsake des Pianistes,

which had been advertised to

subscribers of the Parisian Revue

et Gazette musicale some

weeks earlier. Rossini’s

publisher Troupenas took legal

action against his rival Maurice

Schlesinger because of this

unauthorised publication.

(Schlesinger was already mixed

up in the clash over the rights

to the Stabat Mater.) It

emerged from the appeal

proceedings of 6 January 1843

(which decided in favour of

Rossini) that ‘it was alleged

that Rossini had penned the

waltz in question for the album

of a foreign princess, who had

made it public’, and that the

piece had already been published

in Germany five years

previously. Rossini never

regarded a dedication as

implying any assignment of

copyright, as the fact that he

inscribed pieces that were

identical or similar for more

than one person also

demonstrates. He used similar

versions of the theme of this

waltz for piano for Eugenia

Puerati, for Madame Charles de

Rothschild (née Adelheid Herz)

and, in 1849, for Elena Bandiera

Ricci.

[13] It was mainly

Rossini’s Péchés de

vieillesse that were

played at his soirées, but they

also featured excerpts from his

operas and, more rarely, from

those by other composers. When

Giuseppe Verdi was the talk of

Paris in 1865, Rossini had the Adagio,

Te sol, quest’anima from

the final trio of Attila

performed. As this has less than

a bar’s lead-in, Rossini wrote

five bars of introduction. He

headed them Ritournelle pour

l’Adagio du Trio d’Attila,

noting underneath ‘Without

Verdi’s permission | Rossini

1865’. There is no evidence that

Verdi himself was present.

[14] The well-known

Viennese music critic Eduard

Hanslick reported that when he

visited Rossini on 18 July 1864,

the composer ‘was so kind as to

play me his harmonisation of the

old Marlborough song. It is

amazing that Rossini of all

people, having never been given

to modulatory subtleties, has

furnished this folk song with a

wealth of ingenious harmonies

and enharmonic surprises.’ The

early-18th-century satirical

song about the Duke of

Marlborough was so popular that

Beethoven, among others, also

arranged it. According to

Norbert Pritsch, the

harmonisation of Marlbrough

s’en va-t-en guerre shows

‘that Rossini turned a simple,

rather trivial melody into a

little musical gem’.

[15] Rossini wrote L’ultimo

pensiero. Un

Rien for ‘Baryton moderne’

and piano ‘for Mr L. Cerruti

(for his album)’. Cerruti

himself wrote the words to it.

In his capacity as consul to the

Italian Embassy in Paris, Luigi

Cerruti (1819– 1893) paid

Rossini a small annual pension

granted by the newly formed

Italian state. Cerruti, whose

own life had been politically

eventful, describes the feelings

of a dying exile. The autograph,

dated ‘Passy, near Paris, 4th

August 1865’, is still in the

possession of Cerruti’s

descendants in Dresden. Patricia

B. Brauner and Daniela Macchione

kindly produced a critical

edition for this recording.

[16] Rossini set four

lines from Pietro Metastasio’s Artaserse,

giving his piece the title

Metastasio. Pour album.

He left out the lover Megabise’s

predictable application of the

analogy to himself (‘Sopito

in dolce oblio | sogno

pur io così | colei

che tutto il dì | sospiro

e chiamo.’). Sergio Ragni

wrote that Rossini may have been

looking for another poem that

could be given a whole range of

settings, like Mi lagnerò

tacendo. However, the

piece remained a one-off and did

not even find a place in the

albums of the Péchés de

vieillesse; it is housed

in Pesaro with the other

unassigned ‘Sins’.

[17] The Petit

souvenir, which is

inscribed ‘presented to her

ladyship Baroness Charlotte

Nathaniel de Rothschild by her

very devoted G. Rossini, Paris,

10th September 1843’, is quite a

substantial composition for such

a dedication. It is neatly

notated on manuscript paper with

a printed, colour decoration

featuring scenes of people

making music and embellishments.

It shows the high regard in

which Rossini held his

dedicatee, the musically gifted

daughter of his banker friend

James de Rothschild. Having

watched her growing up between

1825 and 1836, he had

encountered her again during his

brief return to Paris, newly

married to Nathaniel de

Rothschild, a scion of the

London branch of the family.

[18] In a letter to

Balzac dated November 1834,

Olympe Pélissier mentions

singing in a concert, while

another letter mentions a new

work by Rossini. Did Olympe sing

the cantata Giovanna D’Arco

(which Rossini later dated 1832)

at this concert, which probably

took place on 12 November 1834?

The volume of Prose e versi

(London 1836) by Count Carlo

Pepoli (who wrote the libretto

for Bellini’s I puritani)

casts doubt on this assumption;

the strophes, lines and

structure of the poem Eleonore

d’Este, which Pepoli says

was set to music by Rossini,

show unmistakable similarities

to Giovanna d’Arco.

There is a letter dating from

the 1850s in which Rossini

writes to his friend Luigi

Crisostomo Ferrucci in Florence:

‘Would you care to adapt a few

strophes of Giovanna d’Arco for

me? Come, and we’ll do it

together.’ It would thus appear

that the music was initially

destined for Eleonora’s lovesick

longing for Torquato Tasso and

did not assume the form in which

it is better known today, that

of Giovanna d’Arco,

until much later. What is

certain is that Marietta Alboni

gave a performance of the

cantata at Rossini’s salon on 1

April 1859, with the composer at

the piano.

Reto Müller

Translation: Susan

Baxter

|

|