|

|

3 LPs

- 6.35472 FK - (p) 1980

|

|

| 8 LCDs -

9031-71719-2 - (c) 1990 |

|

KLAVIERSONATEN

- Volume 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van

BEETHOVEN (1750-1827) |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 3 C-dur, Op. 2 Nr. 3 - Joseph

Haydn gewidmet (Komponiert um

1795)

|

|

24' 08" |

|

|

-

Allegro con brio

|

9' 30" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Adagio |

6' 43" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegro |

3' 05" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Allegro assai

|

4' 50" |

|

A4 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 7 D-dur, Op. 10 Nr. 3 - Der

Gräfin Anna Margarete von Browne

gewidmet (Komponiert 1796/98)

|

|

22' 21" |

|

|

-

Presto

|

6' 56" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Largo e mesto

|

8' 27" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Menuetto: Allegro

|

2' 50" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegro

|

4' 08" |

|

B4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 14

cis-moll,

Op. 27 Nr. 2 Sonata

quasi una fantasia

"Mondscheinsonate" -

Dem Gräfin

Giulietta

Guicciardi (Komponiert

1801)

|

|

13' 16" |

|

|

-

Adagio sostenuto

|

4' 46" |

|

C1 |

|

-

Allegretto |

1' 32" |

|

C2 |

|

-

Presto agitato

|

6' 58" |

|

C3 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 25

(Sonatine)

G-dur,

Op. 79 (Komponiert

1809)

|

|

7' 44" |

|

|

-

Presto alla tedesca

|

3' 00" |

|

C4 |

|

-

Andante |

2' 48" |

|

C5 |

|

-

Vivace |

1' 56" |

|

C6 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 23 f-moll,

Op. 57

"Appassionata" - Dem

Grafen Frany von

Brunswik gewidmet

(Komponiert 1804/06)

|

|

21' 17" |

|

|

-

Allegro assai · Più allegro

|

8' 35" |

|

D1 |

|

-

Andante con moto

|

5' 08" |

|

D2 |

|

-

Allegro ma non troppo: Presto

|

7' 34" |

|

D3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 17 d-moll, Op. 31 Nr. 2 "Der Sturm"

(Komponiert

1801/02)

|

|

24' 27" |

|

|

-

Largo · Allegro

|

8' 27" |

|

E1 |

|

-

Adagio

|

7' 10" |

|

E2 |

|

-

Allegretto

|

8' 50" |

|

E3 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 18 Es-dur, Op. 31 Nr. 3

(Komponiert 1801/02)

|

|

21' 45" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

7' 33" |

|

F1 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegretto vivace

|

4' 27" |

|

F2 |

|

-

Menuetto: Moderato e grazioso |

5' 07" |

|

F3 |

|

-

Presto con fuoco

|

4' 38" |

|

F4 |

|

|

|

|

Rudolf BUCHBINDER,

Klavier (Steinway-Flügel)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Telefunken

| 6.35472 FK | 3 LPs | LC 0366 |

durata: 46' 29" · 43' 17" · 46'

12" | (p) 1981 | ANA | stereo

|

|

|

Edizione CD

|

|

Teldec |

9031-71719-2 | 8 CDs | LC 3706 |

(c)

1990 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonaten Nr. 1-32

Teldec | 8.43415 ZK | 1 CD

| LC 3706 | (c) 1986 | DDD/DMM

| stereo | Klaviersonaten Nr. 3

Teldec

| 8.43476 ZK | 1 CD | LC 3706 |

(c)

1987 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 7

Teldec |

8.42913 ZK | 1 CD | LC 3706

| (c)

1983 | DDD/DMM | stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 14, 23

Teldec

| 8.43478 ZK | 1 CD

| LC 3706 | (c)

1987 | DDD/DMM |

stereo |

Klaviersonate Nr. 25

Teldec

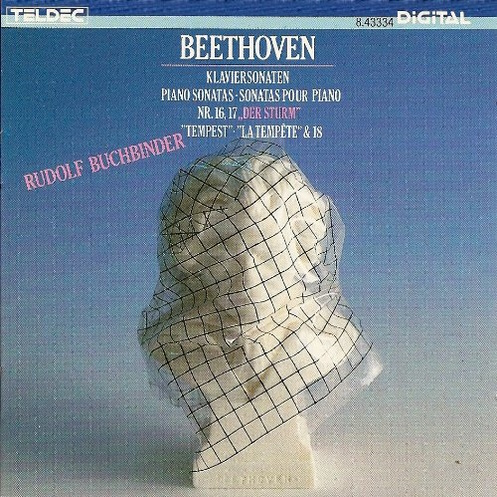

| 8.43334 ZK |

1 CD | LC 3706

| (c)

1986 | DDD/DMM

| stereo |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 17, 18

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

-

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

-

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Ludwig

van Beethoven, Gemälde von J. W.

Mähler, 1815

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHBINDER

BEETHOVEN

32 KLAVIERSONATEN

3 LPs - 6.35472 FK - (p) 1980

2

LPs - 6.35490 FK - (p) 1981

3 LPs -

6,35581 FK - (p) 1982

3 LPs -

6.35596 FK - (p) 1982 |

RE-RELEASE

ON

COMPACT DISC (DMM)

1 CD - 8.43415 ZK - (c) 1986

(Nr.3)

1 CD - 8.43476 ZK

- (c) 1987 (Nr.7)

1 CD - 8.43476 ZK

- (c) 1987 (Nr.7)

1 CD -

8.42913 ZK - (c) 1983

(Nr.14,23)

1 CD -

8.43478 ZK - (c) 1987

(Nr.25)

1 CD -

8.43334 ZK - (c) 1986

(Nr.17,18)

|

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 3 C-dur, Op. 2

Nr. 3

Even the

first compositions produced by

Beethoven in Vienna were fully

mature works: the three Piano

Trios of op. 1, written in

1793/4 and dedicated to his most

eminent patron, Prince Carl

Lichnowsky, of whom he was to

say in 1805: ”He is truly one of

my most faithful friends and the

promoter of my art - something

fairly unusual in that class,”

and the three Piano Sonatas of

op. 2, dedicated to Joseph

Haydn. When Beethoven moved to

Vienna from Bonn in the autumn

of 1792 - temporarily, as he

thought - he became Haydn’s

pupil for about a year. Not

merely does the dedication

express the customary gratitude

shown to a teacher, but the

three sonatas represent what the

young composer, whom Haydn had

as early as 1795 described, in a

diary entry, as a genius, had

learnt from his teacher’s style

rather than from his lessons. In

this context it is worth

recalling the prophetic words

with which Count Waldstein

concluded his entry in

Beethoven’s album on the eve of

his departure from Bonn: “By

unremitting diligence you will

receive the spirit of Mozart

from the hands of Haydn."

In 1795 Beethoven wrote the

three sonatas of op. 2,

incorporating in them some

previously composed material,

and they were published a year

later. The richness and

inventiveness which they display

is divorced from any kind of

formalism. No. 3 in C, one of

Beethoven's most frequently

played sonatas, is conceived on

the largest scale and contains

elements of orchestral

sonorities, as opposed to the

"chamber music” scale of

No. 1 and the pianistic

virtuosity cf No. 2. The first

movement of this sonata is

sometimes described as a piano

concerto in disguise, because of

the interesting changes in the

tone colour and figuration, and

particularly on account of the

strange free cadenza which is

interpolated between the end of

the recapitulation and the coda.

However, Beethoven’s music is

particularly characterised by

the fact that traditional types

of style, such as ”chamber

music,” “pianistic” etc. are

constantly reshaped, discarded,

indeed stripped of their

traditional, typical effect. As

far as the A flat major cadenza

in the first movement is

concerned, it is reminiscent

neither in its placing nor in

its internal form of a true

concerto cadenza; this passage

is free improvisatory

soliloquising, and a last

product of the surprise element

in this movement, which is

derived from constantly changing

confrontations with and

digressions from the terse

opening motif, which, taken by

itself, would have led one to

expect the movement to take an

entirely different course.

The second movement, an Adagio

in the third-related key

of E which moves through

manifold ranges of expression as

though in a dream, appears to be

just one vast elaboration of the

improvisation at the end of the

first movement. In 1842

Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny

stated in his notes on the

interpretation of the sonatas

that this adagio already

displayed a romantic tendency

that later enabled Beethoven to

create a type of composition

which raised instrumental music

to the level of painting and

poetry. Particularly strange is

the sudden eruption in the

second half, fortissimo, in the

contrasting key of C, an

isolated variant of the two bars

of the first subject - but it

turns out to be merely an

obvious harking back to the

beginning of the first movement;

material that has already been

encountered is treated as though

it were entirely new. Details

such as these indicate what

Beethoven put into his

compositions. In the Scherzo,

strangely enough, the violence

does not flare up until the Trio

is reached and the triplets

create the illusion of increased

speed. The motivic element of

the movement centres, in

essence, on the contrast between

the major and minor seconds in

the two versions of the first

motif. At the very end of the

coda, which flits from mighty

octave leaps to a pianissimo,

the interval is reversed and the

second rises from B to C. A

reworking of the material down

to its smallest components,

typical of Beethoven’s writing

from then on, is one of his

finest legacies from Haydn.

Piano

Sonata Nr. 7 D-dur, Op. 10

Nr. 3

The three sonates

of op. 10 were written shortly

afterwards, in the periodo

1796/98, as was the Sonata op.

7; they were published in 1798

along with the Trio for

Strings op. 9 Op. 10 No. 1 in

C minor is the most popular,

but the most important,

without a doubt, is No. 3. Its

core is the slow movement,

Largo e mesto, a mighty

lamentation, a tragic song of

mourning in pallid hues,

expressing in its nuances of

light and shade, as Beethovens

friend and amanuensis Anton

Schindler claims he was told,

the state of mind of someone

who has become a prey to

melancholy. This largo

introduces new sounds into

piano music which exceed the

melancholy of some of Mozart’s

pieces or the expressive

eccentricity of C. P. E. Bach;

some passages almost seem to

anticipate Liszt. Three

decades later Czerny wrote:

”This Adagio is one of

Beethoven’s most magnificent,

but also most melancholy.”

However, the irritation caused

to Beethoven’s contemporaries

by this piece, which they felt

to be obscurely dark, was

expressed in a review in 1798:

”The superfluity of ideas, of

which an aspiring genius

generally manages to rid

himself, still frequently

drives him veritably to pile

his wild thoughts on top of

one another and to arrange

them in a most peculiar

manner. Thus he often descends

to a sombre art or an

artificial sombreness which is

a drawback rather than an

advantage for the overall

effect...” Evidently it was

not only the late works of

Beethoven that appeared

incomprehensible. The bright

first movement is in marked

contrast; incessant rapid

motion, the progress of which

is almost entirely derived

from a single short motif.

Similarly, the Finale, with

its wittily cheerful interplay

of question and answer. The

only movement which seems to

have any emotional connection

with the Largo, by providing

some relaxation, is the

Minuet, which is in major

throughout; as in op. 2, No.

3, the allegro tempo does not

assert itself until the middle

section, with its demanding

triplets and pointed upbeats,

derived from the minuet

subject, is reached.

Piano

Sonata Nr. 14 cis-moll, Op.

27 Nr. 2 "Mondscheinsonate"

Beethoven called both works of

op. 27, written in 1800/01,

”Sonata quasi una Fantasia,”

in order to draw attention to

their deviation from the usual

form; the movements merge into

one another as in a Fantasia,

and in op. 27. No. 1 they are

even formally interwoven. The

first movement is ternary, with

two different tempi; towards

the end of the last movement

the Adagio is echoed - an

anticipation of techniques

employed by Beethoven in his

late works. The Sonata in C

sharp minor, although, and

perhaps because, it is

certainly not one of his

greatest works, has attained a

popularity that is not easily

explained. Thus, a Russian

Beethoven enthusiast

complained that in Paris at

the end of the 1820s only

three of Beethoven’s sonatas

were ever played: the one in A

flat op. 26; op. 27, No. 2 and

the ”Appassionata.” Beethoven

himself is supposed to have

told Czerny that people were

always talking about the

sonata in C sharp minor, for

all that he had certainly

written better pieces. No

doubt the work owes much of

its popularity to the first

movement. The Berlin critic

and poet Ludwig Rellstab, for

instance, imagined himself in

a boat on the moonlit Lake of

Lucerne (hence the name

"Moonlight Sonata”); others

heard in it a lament for the

dead, Czerny wrote: ”It is a

nocturnal scene with the

voices of a ghost mourning

from afar." There has been

speculation, too, about a link

beetwen the work and the

dedicatee, the young Countess

Giulietta Guicciardi, to whom

Beethoven was close; she may

possibly have been the

addressee of the much debated

letter to the “Immortal

Beloved.” From that point of

view the sonata is the

pessimistic expression of

hopeless love, which surely is

too romantic, too subjective,

too facile an interpretation.

Examined from the viewpoint of

a fantasia, the Adagio would

appear to be a large, dreamily

improvisatory introduction

followed first by a contrasting

short central movement in the

major in the manner of an

intermezzo, and then by the

principal movement proper, a

Presto in the same key as the

Adagio, C sharp minor, a

taxing piece that races along,

a true sonata movement in

form.

Piano

Sonata Nr. 25 (Sonatine), Op.

79

The Sonatina op. 79, written in

1809, is, like a piece of light

relief, over-shadowed by greater

works: the Choral Fantasia op.

80; the Emperor Concerto; the

String Quartet op. 74; the

incidental music for ”Egmont”

and the Sonata op. 81a "Les

Adieux." In a letter to his

publishers Beethoven expressly

described the work which,

incidentally, he wanted

published with its predecessor,

op. 78, as a ”Sonatine facile."

Until the relevant sketches were

discovered it was thought that

this was an early work which,

like the piano sonatas of op. 49

or the Capriccio “The rage over

the lost penny," he had simply

published much later. Many

details, however, militate

against this view, for example

the not immediately apparent

structural and thematic linking

of the three movements by the

interval of a third, which is

common to all of them. As

Joachim Kaiser puts it, ”anyone

who analyses the sonata

carefully should be able to

prove without difficulty

something that no sensible

person would dispute, namely

that this work, which is never

tediously regular or

pedantically dry, obviously

comes from the hand of the

mature Beethoven.” Incidentally,

Czerny omits it from the

catalogue of sonatas, as he does

both works of op. 49; he

therefore, unlike later

catalogues, acknowledges not 32

but only 29 "great sonatas,

which by themselves would suffice

to render his name immortal."

Piano

Sonata Nr. 23 f-moll. Op. 57

"Appassionata"

The ”Appassionata,” the name of

which, like so many others, is

not Beethoven’s own but was

added by a publisher in 1834,

was composed in 1804/05, in a

period which saw a number of

other great works, among them

the Waldstein Sonata, the Triple

Concerto and notably ”Fidelio.”

Sketches for the sonata, which

is dedicated to Beethoven's

friend and patron Count Franz

von Brunsvik, are contained in a

notebook which is mostly taken

up with work on the opera.

Beethoven’s pupil Ferdinand Ries

tclls the following story of the

composition of the sonata:

"Throughout the whole of a long

walk, during which we lost our

way to such an extent that we

did not return to Döbling until

eight o’clock, he had been

muttering and sometimes howling

to himself, always up and down,

without singing any specific

notes. When I asked him what he

was doing he replied: ’I have

just thought of a theme for the

final Allegro of the sonata.’

When we got indoors, he hurried

to the piano without even

removing his hat. I sat down in

a corner, and soon he had

forgotten my presence. Then he

thumped away for at least an

hour at the new, beautiful finale

of the sonata.” This finale,

linked directly to the tranquil

variations of the third movement

by strident dissonances, rages

like a ceaseless tempest;

virtuosity, never an end in

itself, is totally subservient

to expressiveness. The movement

hardly ever strays from the

minor, there is no gleam of

light, no solace. Indeed in the

presto coda, which at first

introduces a new, pounding

theme, the furious arpeggios and

broken chords which dominate the

whole movement develop into

thunderous sounds that erupt

into an apocalyptic uproar. In

abstract terms the first

movement, too, is largely

constructed of simple broken

triads; the exposition is not

repeated in the usual manner,

but is like a fantasia in the

grand concertante style with

continuous variation on two

themes, the second one being

merely a kind of free inversion

of the first. As in the Finale,

there is a stretta coda, but

after hugely massed chords it

subsides quite unexpectedly into

a wan pianissimo. The whole

movement is permeated by a

knocking motif which in the

recapitulation disturbingly

underlies the first subject for

some time and seems to

foreshadow the opening of the

fifth symphony.

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 17 d-moll, Op. 31

Nr. 2 "Der Sturm - Nr. 18

Es-dur, Op. 31 Nr. 3

Beethoven wrote the three

sonatas of op. 31 in 1801/02,

during a period of upheaval

marked by his personal crisis,

the first signs of his deafness

(”Heiligenstadt Testament,"

1802); but it was also a period

of artistic upheaval. “I am not

very pleased with the works that

I have written to date. As from

today, I shall embark on a new

course” is what, according to

Czerny, Beethoven said to the

violinist Wenzel Krumpholz

(presumably in 1802). This new

course manifested itself most

clearly in the ”Eroica,” written

in 1803, and representing an

entirely new symphonic style;

but it is also evident in his

piano works, such as the

Variations op. 35 (1802) and not

least in the Sonatas of op. 31,

particularly in Nos. 2 and 3,

which in many respects appear to

continue the experiments in form

contained in the two sonatas

”Quasi una Fantasia” of op. 27.

Czerny: "Shortly after this

event” (the remark quoted above)

"three sonatas appeared, in

which can be observed the

partial realisation of his

resolve.” Exceptionally, the

Sonata in D minor has only three

movements. The middle movement

is a broadly conceived Adagio

with vast sonorities, fanning

out in an almost orchestral

fashion, in which various

registers answer one another and

a sublime, slow melody is

embellished by remarkably

detailed figurations. The last

movement is an Allegretto,

clearly developed from the

broken chord; its form is a

mixture of rondo and sonata.

According to an anecdote related

by Czerny, Beethoven got his

inspiration for the kinetic

energy which infuses the

movement from watching a

horseman who rode past his

window one day. But when

Schindler questioned the

composer about the significance

of this sonata and of the

”Appassionata," he is said to

have replied, quite casually:

“Read Shakespeare’s ’Tempest’!"

The Sonata in E

flat has four movements ; the

second, however, is a Scherzo in

duple time, of a humorous

character which in the case of

Beethoven means grotesque, full

of surprises and constant

dynamic and rhythmic changes.

The third movement is a brief

Minuet, which appears from its grazioso

strain to be intended as a

substitute for the missing slow

movement. But even more than in

these deviations in form from

the accepted rule, the “new

course” can be discerned in what

may be described as the

developmental character of the

form: the manner in which the

thematic material not only

continues to change, but is

presented not as a structure

which is complete in itself but

as one still in the process of

evolution. Thus the first subject

of the opening movement of op.

31, No. 2 is only recognised as

such when at long last the key

and the basic tempo are

established in bar 21: after a

rudimentary introduction one

does not, as one might expect,

encounter the subject but rather

its continuation and

elaboration. The “subject” - it

barely accords with the accepted

definition of the term - has been

more or less concealed in the

seemingly improvisatory

interplay of the largo broken

chords and violinistic scales of

the opening. In the

recapitulation the “subject” is

even more completely obscured by

recitativic interpolations,

rather as though it were a

development section; there is no

corresponding D minor passage

(as in bar 21), but in its place

there appears a passage in the

contrasting key of F sharp

minor, the opening key of the

development, which gives an

impression of being entirely

new. No less improvisatory is

the beginning of the Sonata in E

flat, opening with a bird call in

the subdominant and thus

strictly dissonant, as though it

were an answering phrase

replying to a question that has

not actually been posed. The

same device is again employed in

the last movement of the same

sonata: the first figure is not

like a beginning, but is a turn

of phrase which is a typical

ending.

Jean

Meuchtelbach

|

|

|

|

|