|

|

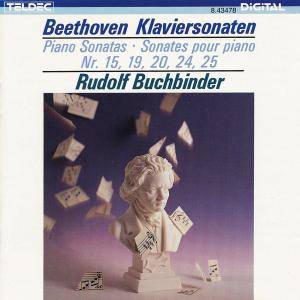

1 CD -

8.43477 ZK - (c) 1987

|

|

DIE

KLAVIERSONATEN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ludwig van

BEETHOVEN (1750-1827) |

Klaviersonate

Nr. 9 E-dur, Op. 14 Nr. 1 - Der

Baronin Josefa von Braun gewidmet

(Komponiert 1798/99)

|

|

11' 40" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

5' 45" |

|

1 |

|

-

Allegretto

|

2' 56" |

|

2 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegretto comodo

|

2' 59" |

|

3 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 10 G-dur,

Op. 14 Nr. 2 - Der Baronin

Josefa von Braun gewidmet

(Komponiert 1798/99) |

|

14' 24" |

|

|

-

Allegro

|

6' 33" |

|

4 |

|

-

Andante |

4' 39" |

|

5 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegro assai

|

3' 12" |

|

6 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 22 F-dur,

Op. 54 (Komponiert

1804)

|

|

11' 05" |

|

|

-

In Tempo d'un Menuetto

|

5' 09" |

|

7 |

|

-

Allegretto

|

5' 56" |

|

8 |

|

Klaviersonate

Nr. 12 As-dur,

Op. 26 - Dem Fürsten Carl

von Lichnowsky gewidmet

(Komponiert 1800/01) |

|

18' 55" |

|

|

-

Andante con Variazioni

|

7' 23" |

|

9 |

|

-

Scherzo: Allegro molto

|

2' 31" |

|

10 |

|

-

Marcia funebre sulla morte d'un Eroe

|

6' 37" |

|

11 |

|

-

Allegro |

2' 30" |

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

Rudolf BUCHBINDER,

Klavier (STEINWAY-Flügel)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Teldec

Studio, Berlin (Germania) -

novembre 1981 (Nr. 9, 10, 22)

Kongreßsaal, Villach (Austria) -

luglio 1980 (Nr. 12)

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Telefunken

| 6.35596 FK - Vol.4

| 3 LPs | LC 0366 |

durata: 55' 39" · 42' 47"

· 65' 59" | (p) 1982 | ANA

| stereo | (Nr. 9, 10, 22)

Telefunken

| 6.35490 FK - Vol.2 | 3

LPs | LC 0366 | durata:

53' 24" · 41' 14" · 49'

53" | (p) 1981 | ANA |

stereo | (Nr. 12)

|

|

|

Edizione CD

|

|

Teldec |

8.43477 ZK | 1 CD | LC

3706 | durata: 56' 00" |

(c) 1987

| DDD/DMM | stereo

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Mohr

|

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Siegbert

Ernst (Nr. 12); Eberhard Sengpiel

(Nr. 9, 10, 22)

|

|

|

Cover design

|

|

Holger

Matthies

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| THE 32

PIANO SONATAS (10 CDs DMM) |

Piano

Sonatas Nr. 9 and 10, Op. 14 Nr.

1 and 2

These two sonatas of op. 14,

composed at the same time as the

”Pathétique”, were also published

in 1799. They are in the

small-scale three movement form,

cheerful, uncomplicated and

technically undemanding; Czerny

described the first movement of the

sonata in G as an exceptionally

charming and lighthearted

composition. The fact that they

were contemporaneous with the

”Pathétique” proves yet again that

any attempt to interpret a work as

the reflection of the personal

circumstances of its composer at

the time when it was created is

fraught with dangers. If the

”Pathétique” is to be understood

as a tragic revolt against

Beethoven's incipient deafness,

how can this be reconciled with

the calm serenity of op. 14,

written at the same time? Style in

music simply cannot always be

related to the frame of mind of

its composer, for all that bad

exegetical literature still makes

this claim; like form and genus in

music, it has its own tradition.

Conceivably the reduced rechnical

problems (the two even easier

sonatinas of op. 49, written in

1796, were, after all, not

published until 1805) are to be

understood as a compliment to the

dedicatee, the Baroness Braun, who

is not known to have been a

particularly distinguished

pianist. Her husband was, however,

at that time deputy director of

Vienna's two imperial court

theatres, and this may throw some

light on the purpose of the

dedication. Soon afterwards

(1801-02) Beethoven arranged op.

14, No. 1 for string quartet,

writing full of pride to the

publisher “I know that nobody else

can follow in my footsteps as

easily as I can.”

Piano Sonata Nr. 22 F-dur, Op.

54

This short work, written in 1804,

contrasts strangely with the two

great, quasi-symphonic sonatas

opp. 53 and 57, between which it

is placed chronologically. In some

respects it follows on the

experiments of opp. 26 and 27,

since neither of its two movements

is in true sonata form. The first

movement consists of two sharply

contrasting elements: a short

exposition, strongly reminiscent

of the minuet style of a past age,

almost a stylistic quotation,

Czerny rightly referred to its

old-fashioned character, and this

is borne out by the anachronistic

marking ”in tempo d’un Menuetto”

in place of the more usual ”in

tempo di Menuetto”. The longish

middle section is most certainly

not a trio, but more like a

rumbustious orchestral scherzo

with its fierce sforzato accents

going against the grain. No less

strange is the second movement.

Although the pattern of its motion

- incessant semiquaver figuration

in 2/4 time - is the same as that

of the last movements of opp. 26

and 27, No. 1, its form cannot be

labelled, instead, as in a

kaleidoscope, new configurations

constantly come into existence,

wandering off into the most

distant keys imaginable, all

arising out of a minute seminal

phrase, the broken chords of the

first bar. This movement is a fine

example of Beethoven's masterly

economy of material. Once again,

contemporary critics did not know

what to make of such

”experimental” music, a reviewer

of the first edition, though he

could not fail to recognise its

original inspiration and

unmistakeably mature harmonic art,

went on to say that unfortunately

it was again full of a strange

waywardness. Even Beethoven's

admirer Wilhelm von Lenz,

convinced that this two-movement

sonata was incomplete, wrote, as

late as the 1850s: "We have yet to

meet anyone who has found the

torso of op. 54 at all to his

liking."

Piano Sonata Nr. 12 As-dur, Op.

26

This work and the two sonatas of

op. 27, both subtitled ”quasi una

Fantasia," were all written in the

period 1800/01 and have in common

departures from the traditional

sonata form. This applies

particularly to the first

movements: in the two sonatas of

op. 27 Beethoven used a free

ternary form, whereas op. 26

begins with a set of variations.

Superficially Mozart's great Sonata

in A, K. 331, the first movement of

which is also an Andante con

variazioni, provides the model;

but Beethoven's conception of the

principle of variation, cast for

the first time in a new mould in

op. 26, stretches far beyond the

innocent and cheerful

embellishments of the past. These

are "character variations” in that

each piece has its own,

unmistakeable features. In this

opening movement of op. 26

Beethoven explored, as though for

the first time, the possibilities

inherent in the variation form

which, shortly afterwards (in

1802), were presented in the two

sets of variations op. 34 and op.

35 (the ”Eroica” Variations) "in

an entirely new manner,” as he

proudly wrote to his publishers.

The second substantial departure

from the sonata model in op. 26 is

the replacement of the slow

movement by a ”marcia funebre,”

i.e. a funeral march, subtitled

”sulla morte d'un Eroe” ("on the

death of a hero”). While in the

”Eroica” (subtitled ”to celebrate

the memory of a great man”) actual

references to Napoleon, the

contemporary hero of world

history, and the tradition of

depicting battles in music were

interwoven in an overall poetic

impression, op. 26 cannot be

described as a “heroic” sonata. So

far no clues have been discovered

as to Beethoven's choice of a

funeral march, nor about its

subtitle. Nonetheless the movement

soon became famous, it was

published on its own in the same

year as the first edition of the

sonata proper - 1802 - and has

continued to appear in that form;

Beethoven himself orchestrated it

in 1815 as incidental music for a

play; and after his death in 1827

Ignaz Ritter von Seyfried

published an arrangement of the

piece with added vocal quartet,

entitled ”Beethoven’s funeral.”

In complete contrast, this severe,

solemn march is followed by a

deliberately lighthearted finale

rippling along in ceaseless

semiquavers. This sonata, like the

”Pathétique” op. 13 and the Trios

op. 1, is dedicated to Prince Carl

von Lichnowsky, Beethoven's most

important patron, of whom he said

in 1805: "He really is -

exceptionally for one in that

position - one of my most faithful

friends and supporters of my art.”

|

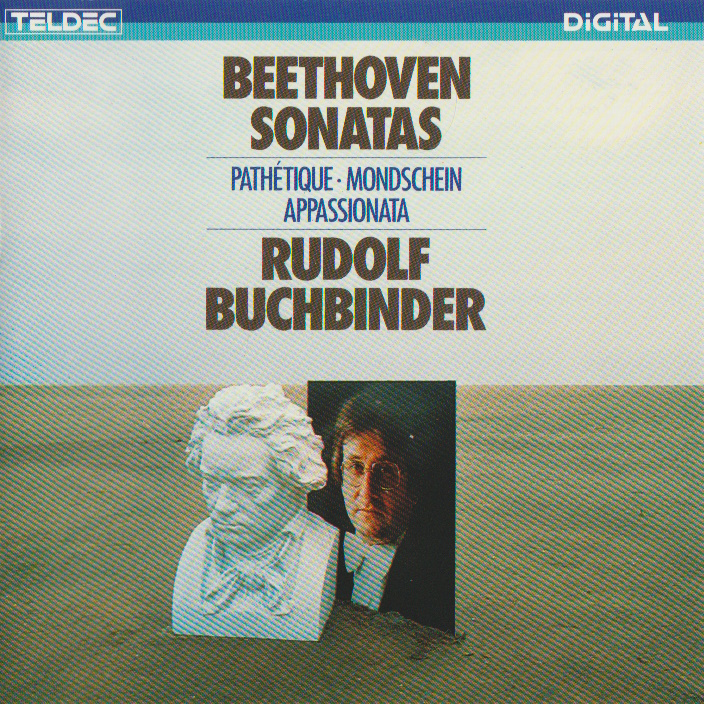

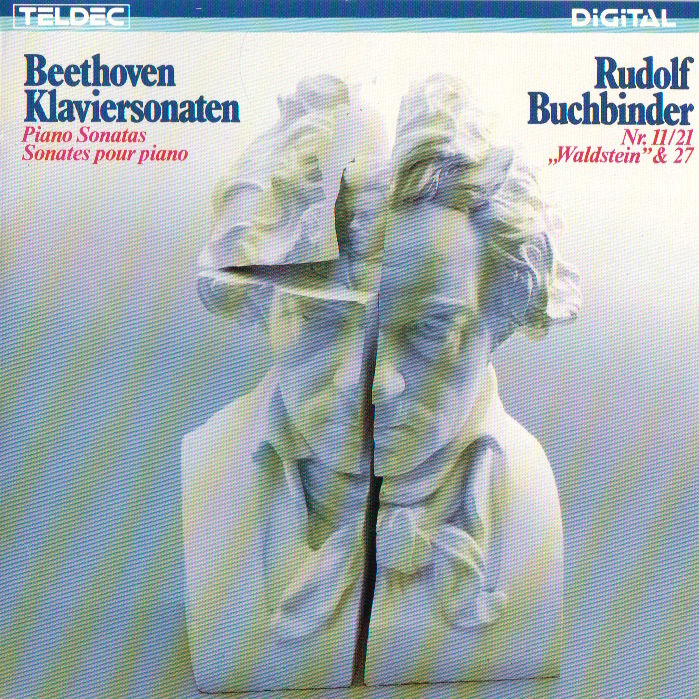

1 CD - 8.42761 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43027 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43027 ZK - (c) 1984

1 CD -

8.43206 ZK -

(p) 1985

1 CD - 8.43415

ZK - (p) 1986

1 CD - 8.43477

ZK - (p) 1987

|

1 CD - 8.42913 ZK - (c) 1983

1 CD - 8.43111 ZK - (p)

1985

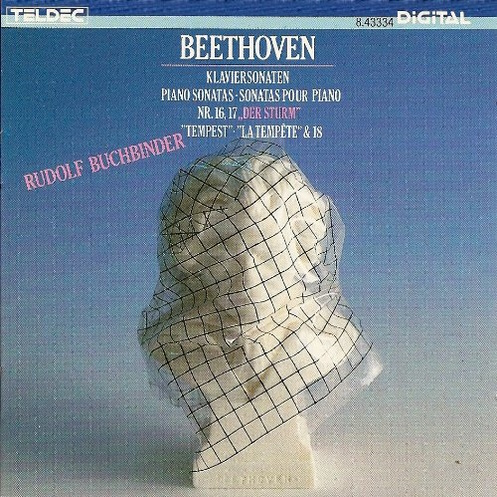

1 CD - 8.43334 ZK

- (p) 1986

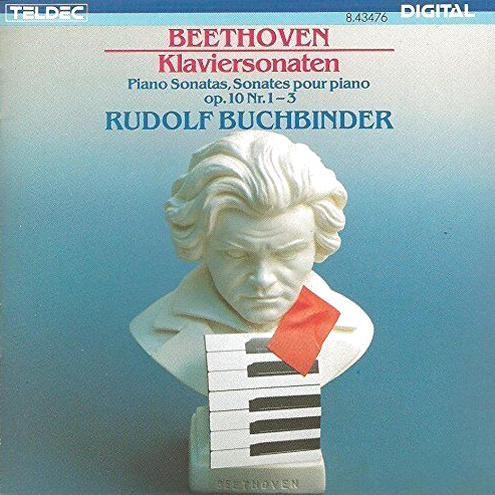

1 CD - 8.43476

ZK - (p) 1987

1 CD - 8.43478

ZK - (p) 1987

|

|

|

|

|