|

|

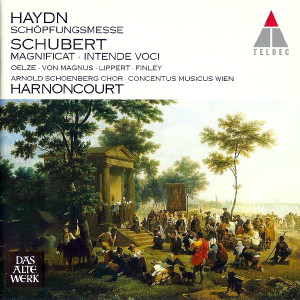

1 CD -

3984-26094-2 - (p) 2000

|

|

| Johann Nicolaus de la

Fontaine und d'Harnoncourt-Unverzagt

(1929-2016) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz

Schubert (1797-1828) |

Magnificat in

C major, D 486 - for soloists

(SATB), chorus and orchestra |

|

8' 59" |

|

|

-

Magnificat anima mea Dominum

|

2' 26" |

|

1

|

|

- Deposuit

potentes de sede |

2' 25" |

|

2

|

|

- Gloria

Patri |

4' 08" |

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz Joseph Haydn

(1732-1809) |

Schöpfungsmesse

in B flat major, Hob. XXII:13 - for soloists (SATB), chorus

and orchestra |

|

44' 01" |

|

|

Kyrie |

6' 01" |

|

|

|

- Adagio

|

1' 54" |

|

4

|

|

- Allegro

moderato

|

4' 07" |

|

5

|

|

Gloria |

10' 36" |

|

|

|

- Gloria |

7' 24" |

|

6

|

|

- Quoniam |

3' 12" |

|

7

|

|

Credo |

11' 59" |

|

|

|

- Credo |

2' 18" |

|

8

|

|

- Et

incarnatus

|

3' 00" |

|

9

|

|

- Et

resurrexit |

4' 41" |

|

10

|

|

Sanctus |

3' 07" |

|

11

|

|

Benedictus |

5' 54" |

|

12

|

|

Agnus

Dei |

6' 24" |

|

|

|

- Agnus Dei

|

3' 26" |

|

13

|

|

- Dona |

2' 58" |

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Franz Schubert |

Intende voci in B flat major,

D 963 - aria for tenor, chorus and

orchestra |

|

11' 59" |

15

|

|

|

|

|

| Christiane Oelze,

Soprano |

|

Elisabeth von

Magnus, Contralto

|

|

| Herbert Lippert,

Tenor |

|

| Gerald Finley,

Bass |

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorus

Master

|

|

|

|

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (with original

instruments)

|

|

| -

Erich Höbarth, Violin |

-

Herwig Tachezi, Violoncello |

|

| -

Alice Harnoncourt, Violin |

- Dorothea

Guschlbauer, Violoncello |

|

| -

Karl Höffinger, Violin |

-

Andrew Ackerman, Violone |

|

| -

Helmut Mitter, Violin |

-

Denton Roberts, Violone |

|

| -

Anita Mitterer, Violin |

-

Hans Peter Westermann, Oboe |

|

| -

Walter Pfeiffer, Violin |

-

Marie Wolf, Oboe |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter, Violin |

-

Gerald Pachinger, Clarinet |

|

| -

Thomas Fheodoroff, Violin |

-

Herbert Failtynek, Clarinet |

|

| -

Annelie Gahl, Violin |

-

Eleanor Froelich, Fagott |

|

| -

Silvia Walch-Iberer, Violin |

-

Christian Beuse, Fagott |

|

| -

Barbara Klebel, Violin |

-

Hector McDonald, Horn |

|

| -

Peter Schoberwalter junior, Violin |

-

Georg Sonnleitner, Horn |

|

| -

Christian Tachezi, Violin |

-

Andreas Lackner, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Irene Troi, Violin |

-

Herbert Walser, Naturtrompete |

|

| -

Mary Utiger, Violin |

-

Sebastian Krause, Posaune |

|

| -

Lynn Pascher, Viola |

-

Gerhard Proschinger, Posaune |

|

| -

Gerold Klaus, Viola |

-

Dieter Seiler, Pauken |

|

| -

Ursula Kortschak, Viola |

-

Herbert Tachezi, Orgel |

|

| -

Dorle Sommer, Viola |

|

|

|

|

| Nikolaus

Harnoncourt |

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione

|

| Pfarrkirche,

Stainz (Austria) - luglio 1999 |

|

Registrazione

live / studio

|

| live |

Producer

/ Engineer

|

Wolfgang

Mohr / Martina Gottschau / Tobias

Lehmann / Michael Brammann

|

Prima Edizione CD

|

| Teldec

Classics "Das Alte Werk" - 3984-26094-2

- (1 cd) - 63' 15" - (p) 2000 - DDD |

|

Prima

Edizione LP

|

-

|

|

|

Notes

|

"Opus

summum viri summi Joseph

Haydn" - “the greatest work of the

greatest man Joseph

Haydn”: thus Haydn’s contemporary, the

composer Johann Adam Hiller, wrote in

block letters on his copy of the Schöpfungsmesse.

Haydn’s penultimate setting of

the words of the

Mass owes its sobriquet -

"Creation Mass" - to a

self-quotation from his oratorio The

Creation, which had received its

first performance in 1798.

According to his early biographer

Georg August Griesinger:

In die Mass that Haydn wrote

in 1801, it

occurred to him while

working on the "Agnus Der, qui tollis

peccata mundi" that weak mortals

generally sin only against moderation

and chastity So he set the words "Qui

tollis peccata, peccata mundi" to the

trifling melody that accompanies the

words in The Creation, “Der thauende

Morgen, o wie

ermuntert er" in order that this

profane thought should not be

too conspicuous, however he

let the

full chorus enter immediately

aferwards with the

“Miserere”.

Griesinger is wrong, in fact, when he

refers to the Agnus Dei, as the

quotation from The Creation

occurs at the words “Qui tollis

peccata mundi" in

the Gloria. Although it appears there

only once, The Creation was so

well known in Vienna that the allusion

was immediately understood. Moreover,

the love duet for Adam and Eve from

which the quotation is taken had

already been published separately in

the Allgemeine

Musikalische Zeitung and

in this way had reached an even wider

audience. But Haydn was criticised for

taking over this "profane

thought" - and criticism came from the

highest quarters: when the imperial

court planned a performance of the

Mass, the Empress Maria Christina

expressed her disapproval of the

passage, and Haydn was obliged to

alter it: the surviving copies of the

score and parts in the Vienna Hofburgkapelle

contain no trace of the offending

quotation. In the longer term, however

Haydn’s original version was to gain

universal acceptance.

Only recently had performances of

large-scale orchestral settings of the

Mass again become possible in Vienna:

in 1782 the Emperor Joseph II,

responding to Enlightenment ideas, had

decreed a radical simplification of

church music, a decree that effectively

spelt the end of concert

performances of Latin church music for

the next decade and a half. Not until

1797 was his edict

formally lifted by Franz II.

Even so, Haydn had already begun to

write orchestral Masses

the previous year. He had returned to

Austria from his second and last

visit to England in 1795, when

his employer Prince Nikolaus II of

Esterházy had asked

him to resume direction of his court

orchestra. At the same time,

however, he released Haydn from his

duties as a composer, making only one

exception: Haydn was to write an

annual Mass for the name-day of his

wife, Princess Maria Hermenegild.

lt is to this arrangement that we owe

the six great Masses that Haydn wrote

between 1796 and 1802. Haydn himself

was in no doubt about their merits -

he once told Griesinger: "I'm

a tiny bit proud of my Masses." Prince

Esterházy initially

had these works performed at his

residence in Eisenstadt. Only later,

after Joseph II's

decree had been rescinded, were they

also heard in Vienna.

The Schöpfungsmesse

was first perfonned at Eisenstadt on 13

September 1801. By now Haydn

was at the very peak of his powers

and, more importantly, could draw on

the experiences gleaned during his two

visits to England and already

enshrined in his "London"

Symphonies. He now transferred the

principle of motivic and thematic

development to the field of vocal

music, dispensing with virtuoso arias

and frequently treating the four vocal

soloists as a self-contained ensemble

in opposition to the choir, as emerges

from the opening four-part

Kyrie with its slow

introduction and motivic

links between its different sections.

The high point of the Gloria is the

large-scale fugue on the words "ln

gloria Dei patris", while the Credo is

notable for Haydn's ability to marry

words and music in

pursuit of heightened expression:

note, in particular, his setting of

the words “descendit de coelis"

and the whole of the "Crucifixus". The

Sanctus is largely given over to the jubilant

strains of the "Hosanna". And

the work ends with a plea for peace in

the form of the Agnus Dei, a plea that

Haydn delivers with compelling

confidence.

Franz Schubert is now best known for

his lieder, piano works

and orchestral music. But he also

wrote a great deal of sacred music,

including Masses, liturgical works and

songs with religious words. Although

1815 is regularly described as his

“year of song” on account of the 150

or so lieder - including Erlkönig -

that he wrote during this twelve-month

period, it also witnessed the

composition, in September, of his only

setting of the Magnificat, a

hymn for the Virgin Mary that he

divided into three subsections: her

opening words, in which she praises

God and thanks Him for the favour that

He has bestowed on her, are a

resplendent Allegro rnaestoso for the

four vocal soloists, chorus and full

orchestra. The middle section is an

Andante that deals with God's actions

on behalf of the whole

of humankind and is more muted in

expression, with the orchestra reduced

to strings and oboes. And the

following Gloria takes up the paean

from the beginning, raising the pitch

of jubilation even

higher especially in the final

extended “Amen” section.

In October 1828,

only a month before his death and at a

time when he was already seriously

ill, Schubert wrote three shorter

sacred pieces: a Tantum

ergo D 962, a hymn to the Holy

Ghost D 964 and the present Intende

voci D 963. The

words of this last-named piece are

taken from the second verse of the

Fifth Psalm and are an urgent

entreaty asking for God's

assistance. Schubert set this brief

text as a tenor aria with four-part

chorus and orchestra, and it is the

soloist who, following an

instrumental introduction, dominates

the proceedings. The underlying mood

is one of calm and at times achieves

the radiant confidence of Haydn's

setting of the Mass, with only a few

somewhat agitated passages to

disrupt the basic atmosphere, as the

soloist calls on his "King and God" to

answer his prayer. Like so many

other works by Schubert, this

Offertory remained unknown for

decades after his death. Not until

1890 did it receive its first public

performance in

Eisenach.

Wolfgang

Marx

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt (1929-2016)

|

|

|

|