|

|

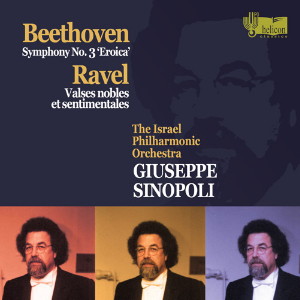

Helicon

- 1 CD - 02-9653 - (p) & (c)

2012

|

|

| Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827) |

Symphony No. 3 in

E flat major, Op. 55 "Eroica" |

|

50' 19" |

|

|

-

I. Allegro con brio |

15' 24" |

|

|

|

-

II. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai |

17' 09" |

|

|

|

-

III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace |

5' 38" |

|

|

|

-

IV. Finale: Allegro molto |

12' 08" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Maurice RAVEL

(1875-1937) |

Valses

nobles et sentimentales |

|

17' 17" |

|

|

-

I. Moderé |

1' 20" |

|

|

|

-

II. Assez lent |

2' 42" |

|

|

|

-

III. Moderé |

1' 43" |

|

|

|

-

IV. Assez animé |

1' 40" |

|

|

|

-

V. Presque lent |

1' 13" |

|

|

|

-

VI. Vif |

0' 55" |

|

|

|

-

VII. Moins vif |

3' 30" |

|

|

|

-

VIII. Epilogue: Lent |

4' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| THE ISRAEL

PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Mann

Auditorium, Tel-Aviv (Israele) -

28 ottobre 1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Producer |

|

Yaron

Karshai |

|

|

Recording

producer |

|

Yuval

Karin |

|

|

Recording

engineer |

|

Eitan

Shamai |

|

|

Mastering |

|

Rafi

Eshel |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Helicon

Classics | 02-9653 | 1 CD - 68' 05" | (p)

& (c) 2012 | DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ludwig van

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3

in E flat major, Op. 55

"Eroica"

Beethoven's view of himself

as an independent artist was

in keeping with the spirit

of his tumultuous times, the

era of the French Revolution

and the Napoleonic Wars. The

first major composer not to

seek court or church

appointments, Beethoven

preferred to work with the

sponsorship of aristocratic

patrons, and on musical

projects primarily of his

own choosing.

His imagination was ignited

by Napoleon, who, as First

Consul of the new French

Republic, seemed to embody

the ideals of the

Revolutionary Era. Beethoven

started work on his Third

Symphony with the intention

of entitling it "Bonaparte".

But soon Napoleon crowned

himself Emperor, becoming in

the composer's view "only

another tyrannical despot,"

and abandoning human values

which Beethoven delt could

not be compromised.

Though musical historians

caution that many anecdotes

about Beethoven's stormy

behavior cannot be

substantiated, there is no

boubt that his revulsion at

Napoleon's ascension to the

throne found violent

expression. On the

hand-written title page of

one copy of the score,

Beethoven erased the name

"Bonaparte" so vehemently

that he tore through the

paper. Beethoven ultimately

wrote on the title page, in

Italian, "Heroic Symphony"

(Sinfonia Eroica), "composed

in memory of a great man."

There has been

speculation that the

symphony expresses, in the

wordless yet profoundly

articulate language of

Beethoven's music, not only

the extra-musical concept of

heroism - the title admits

as much - but also an

overall narrative shape. In

this context, is the

composer's designation of

the second movement, Funeral

March, more than a merely

musical title? If so, do the

other movements also have

meanings, though

unspecified? The most

probable answer is that the

symphony, certainly inspired

by the idea of heroism, may

even be "about" it, but not

in the literal, descriptive

or programmatic sense of

Richard Strauss's Ein

Heldenleben (A Hero's Life),

for example. The narrative

quality of the Eroica is a

purely musical experience.

The eighteenth-century

tradition of the slow

introduction (which

Beethoven follows in hi

first two symphonies) is

decisively and brusquely

shattered by the two short,

loud chords which introduce

the Eroica. The first theme

is scarcely more than the

tonic triad, but presented

with a surprise twist (the

enharmonic flat seventh in

bar seven) which has melodic

and harmonic implications

Beethoven soon exploits.

This first movement was the

longest yet written in the

traditional sonata-allegro

form (exposition -

development - recapitulation

- coda). But it seems taut

and concise due to the

brevity and simplicity of

the themes, and because of

Beethoven's thoroughness in

working out the

possibilities of his

material. The development

section builds to a tutti

passage of sustained

dissonances which, though

they resolve harmonically,

must have been shocking at

the premiere in 1805, and

sound even today as though

they connote struggle or

battle. The abrupt retreat

from this high-point

(staccato quarter-notes in

the strings) is a transition

to a new melody - unexpected

in the middle of a

development section - played

in E minor by the oboe. The

recapitulation is

anticipated by a tentative

incantation of the

movement's first theme, the

second horn outlining the

tonic chord against the

violins' faint suggestion of

an incomplete dominant chord

(an unorthodoxy assumed by

early listeners to be a

wrong entrance by the second

horn player). The coda,

which is almost as long as

the recapitulation, returns

briefly to the new melody

from the development section

before concentrating on

further elaboration of the

main theme.

Neither the simple formal

outline of the Marcia

funčbre nor the movement's

direct emotional message

requires explanation. But it

does pay to remember that

most music, even the art of

great composers, was based,

as a point of departure, on

one or another of the common

types of music familiar to

the general public at the

time of composition. That

familiarity was a basis of

communication from composer

to listener. Taday's

listener, for example,

recognizes parody in Mahler

- sometimes intentionally

grotesque, macabre, or

ironic - of certain types of

music: waltzes and other

dances, military marches,

hymns and popular song. The

listener should also

recognize these and other

types of music, usually

without parody or irony, in

the works of almost all

eighteenth and

nineteenth-century

composers. It is not by

accident that the first

movement of this symphony

resembles a waltz (which

already existed in

Beethoven's time). In the

second movement, the rhythm

and cadence of a military

funeral march are still

familiar - and the impact is

still immediate. Beethoven's

use of the double basses to

conjure the effect of a

snare drum (writing a bass

part separate from the

'celli, unusual at that

time) lends a particularly

lugubrious tone to the

beginning. The short

interlude in C major, with

its brassy recollection of

triumph, leaves the eye no

drier than the sustained

grief of the long fugal

passage which flows from the

next recitation of the march

music. As the movement

reaches its end, the march

is played only in fragments,

like halting speech choked

by grief (an expressive

device used again by

Beethoven at the end of his

powerful Coriolan Overture).

Except in his

Eighth Symphony, Beethoven

replaces the courtly minuet

of the eighteenth-century

symphony with his own rapid,

bustling Scherzo, also in

3/4-time, but so quick that

there is only one beat to

the bar. This movement

dances with lightness and

power, an impression created

in part by the running

staccato quarter notes,

often with larger intervals,

of the bass line. The

unusual use of three horns

in the same key (rather than

the standard pair, or the

occasional two pairs in

different keys) is

highlighted in the Trio

section, which is French

hunting-horn music refined

to suit Beethoven's

expressive purpose. Toward

the end of the Scherzo's

reprise, four bars in duple

time - a simple but

startling effect - are one

example of the freedom and

inventiveness Beethoven had

already developed in this

new style.

The Finale is a set of

variations, some of them

with fugal passages, and the

last several of them

encompassing two changes of

tempo. The highseriousness,

learned craft and noble

inspiration of this music do

not eclipse Beethoven's

outrageous, titanic sense of

humor, which is impossible

to ignore at the beginning

of the movement. The

tremendous flourish of the

opening measures introduces

the most comically pithy of

tunes, played slowly and

pizzicato, on which the

first two variations are

based. But this tune turns

out to be only the bass line

of the actual theme,

eventually played in full by

the oboe. It comes from

Beethoven's earlier ballet

Prometheus and was also the

subject of his Variations

and Fugue on a Theme from

"Prometheus" for piano (now

usually knows as the

"Eroica" Variations). The

significance of this theme

may be more than purely

musical, but if Beethoven

had Prometheus in mind, it

was more likely in

connection with himself as a

creative artist - a creative

force - than with any

long-faded admiration for

Napoleon Bonaparte.

James

Madison Cox

Maurice

Ravel: Valses nobles

et sentimentales

This work by Ravel is a

homage to Franz

Schubert. Ravel himself

stated that its title,

in which two Waltz

cycles by Schubert are

mentioned (Valses Nobles

and Valses

Sentimentales), clearly

indicates his intention

to compose a sequence of

waltzes based on

Schubert. Like many of

Ravel's works, it was

first written for piano

and later orchestrated

by the composer. The

piano version was

composed in 1911 and

although Ravel was still

a controversial figure

at the time, his

reputation as one of

France's greatest

composers had already

been established. The

first public performance

of the Waltzes, by

pianist Louis Aubert, to

whom the work was

dedicated, was booed by

the audience. One year

later, Ravel

orchestrated the work as

ballet music entitled

Adélaide, or the

Language of Flowers. He

also wrote the ballet

plot and conducted the

premiere in April 1912.

This version was

received much more

favorably than the

original one.

The ballet takes place

in Paris around the year

1820, in the salon of

the courtesan Adélaide

has two suitors: the

Duke, who offers her

wealth, and Lorédan,

offering her true love.

The eight Waltzes depict

the eight scenes of the

ballet. The first Waltz

is vigourous and

festive, "spiced" with

Ravelian dissonances.

The scene takes place in

Adélaide's salon, where

couples are dancing and

courting each other

while Adélaide, the

hostess, comes and goes.

The second Waltz depicts

Lorédan's entrance in a

melancholy atmosphere.

He gives Adélaide a

buttercup, a symbol of

love. The music is

written in restrained

elegance with a touch of

sadness prominent in the

elegiac theme. In the

third Waltz, Adélaide

plucks the petals of the

flower one after the

other (like the game "He

loves me, he loves me

not") and discovers that

Lorédan truly loves her.

This Waltz is followed

without a break by the

fourth Waltz, in which

Adélaide and Lorédan

dance together and seem

very much in love. The

moment Adélaide sees the

Duke, she stops dancing.

This Waltz also leads

directly to the

following one. In the

fifth Waltz, the Duke

gives Adélaide

sunflowers and a diamond

necklace, which she

immediately puts on. In

the sixth Waltz

desperate Lorédan tries

his luck once again, but

is rejected by Adélaide.

The seventh Waltz opens

with the Duke begging

Adélaide to save the

last dance for him, but

she refuses and leaves

to look for Lorédan.

Many parts of the final

Waltz resemble fragments

of melodies from the

preceding Waltzes. The

guests leave and the

Duke, who hopes that

Adélaide will ask him to

stay, receives a bunch

of acacia flowers, a

symbol of Platonic love.

He leaves angrily and

Adélaide gives Lorédan a

poppy, a symbol of

forgetfulness. He

rejects the flower and

leaves in despair, only

to return with a gun in

his hand, which he aims

at his head. Adélaide

offers him a red rose

and falls into his arms.

Orly

Tal

|

|

|