|

|

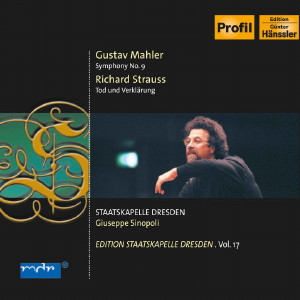

PROFIL

- 1 CD - PH07004 - (c) 2007

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

64'

12" |

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

Symphony

no. 9 in D major

|

|

93' 31" |

|

|

-

1. Andante comodo |

32' 57" |

|

|

|

-

2. Scherzo im Tempo des gemächlichen

Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr

derb |

17' 00" |

|

|

|

-

3. Attacca Rondo. Burleske: Allegro

assai. Sehr trotzig |

14' 15" |

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

56'

16" |

|

|

-

4. Finale. Adagio. Sehr langsam und

noch zurückhaltend |

29' 19" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Richard STRAUSS

(1864-1949) |

Tod und

Verklärung, Op. 24

|

|

26' 57" |

|

|

(Largo

- Allegro molto agitato - Meno

mosso, ma sempre alla breve - Etwas

breiter -

|

|

|

|

|

Molto

appassionato - Allegro molto agitato

- Moderato - Sehr breit - Poco a

poco più calando sin al fine) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Semperoper,

Dresden (Germania):

- 6 aprile 1997 (Mahler)

- 10/11 gennaio 2001 (Strauss) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

MDR Editor |

|

Hermann

Backes (Mahler), Eberhard Jenke

(Strauss) |

|

|

Artistic

recording:

|

|

Günter

Neubert (Mahler). Helga Taschke

(Strauss) |

|

|

Technical

recording: |

|

Eberhard

Bretschneider (Mahler &

Strauss)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

PROFIL - Edition

Günter Hänssler | PH07004 | LC

13287 | 2 CDs - 64' 12" &

56' 16" | (p) 1997 & 2001 by

MDR Kultur | (c) 2007 by Profil

Medien GmbH | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Edition

Staatskapelle Dresden - Vol. 17

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giuseppe

Sinopoli and the

Staatskapelle Dresden with

Mahler and Strauss

The sudden

death of Giuseppe Sinopoli

on April 20, 2001, during a

performance of Aida in

Berlin's Deutsche Oper, hit

us with the elemental force

of an incomprehensible

event. The increasing

distance in time from those

tragic events has done

nothing to diminish the

sense of loss for all those

of us - the musicians of the

Dresden Staatskapelle and

his staff - who were

particularly close to him.

We still retain a vivid

sense of his absolute

devotion to the music, his

precise and yet deeply

considered approach to the

scores and his passion in

interpreting them, the

intensity he brought to the

execution of his high

office, the excellence of

his continuing artistic

duties, the total inner and

outer identification with

"his" orchestra - in Dresden

and in the wider world. We

cannot forget the

intellectual energy that

could draw on the deep wells

of an all-round education,

or the impulses, concepts

and projects that he

initiated with a tireless

determination to succeed

with them while winning

support from others and

leading them further down

the path he had set.We

recall his sheer lust for

life,which communicated

itself to all around him,

and we recollect his acute

and intense observation of

the situation, into which he

was able to draw others too.

We remember his deep need

for mutual understanding and

trust and for human warmth

in his dealings with people

and - more broadly - in the

orchestral sound.That is why

we miss him; many of us

regarded him as a friend and

confidant without in the

slightest losing our respect

and reverence for him. The

recordings of the music we

made in concert keep alive

the sense of this

exceptional teamwork, which

- a rare occurrence in the

music profession - grew more

intense and more stable the

longer it lasted, more

highly charged with its own

aura and less vulnerable to

the passage of time.

The concert programme

manager to the

Staatskapelle, Eberhard

Steindorf, in conversation

with Sinopoli

When Giuseppe Sinopoli

assumed the position of

Principal Conductor of the

Dresden Staatskapelle in

1992, he was considered one

of the world's leading

conductors; already Music

Director of the Philharmonia

Orchestra London, he had

conducted almost all the

great orchestras of the

world and enjoyed

international success in

leading opera houses and

concert halls across Europe,

North America and Japan, as

well as for his many

commercial recordings. And

yet, as he confessed, he was

still searching: not for

ever more perfection but for

the human touch - in music

and in music-making. His

encounter with the

Staatskapelle in September

1987 had given him an

orientation which he

followed consistently from

then on. In a 1998

interview, he said to me: "I

see my first recording with

the Staatskapelle,

Bruckner's 4th Symphony, as

a musical and interpersonal

milestone in my life. The

artistic and human aspect of

our work together thus far

is the reason why I came to

Dresden. Here I encountered

a way of playing in which

music had been preserved as

a treasure island widely

thought to have been lost

without trace, in which

human players reflected upon

what existed, in which one

sensed that music is

actually humanity`s last

hope... This intense

relationship with the

existential is something I

never found until I came to

Dresden. And when I look

back now, I notice that my

awareness of it is stronger

than ever. We make music, we

love our work; that deep

association with the music

(elsewhere Sinopoli once

spoke of the "ethical style

of the orchestra", E. S.)

has remained, and it is

that, I believe, that

underpins our common cause.

It explains why after so

many years we are still

growing closer to one

another, as artists and as

human beings, and will

continue to grow together."

In 1998, the orchestra`s

450th anniversary year,

Sinopoli reminded his

musicians of a particular

aspect of their artistic

work, as if bequeathing them

a legacy: "The Staatskapelle

does not in the first place

have a tradition of dominant

power and dazzling

virtuosity (although it

certainly possesses such

qualities); instead, it has

a tradition of heartfelt

human expression. As long as

it succeeds in preserving

this tradition, it will

uphold its own character and

have a reason togo on making

music." We spoke to Sinopoli

after that first studio

production about his new

plans for recordings and for

concerts in Dresden. In the

autumn of 1989, in the last

days of the old GDR, there

were talks about a formal

association; after two

programmes in the spring of

1990 featuring Schubert and

Bruckner, Schumann and

Strauss, the orchestra

appointed the conductor as

its director, and announced

its appointment publicly

during the Bayreuth Festival

that year. Press questions

about how the engagement of

this top conductor from the

West could be financed in

the east of Germany elicited

the unexpected reply that we

were in agreement about

working together in the

future but had not even

talked about the fee. "With

an orchestra," said Sinopoli

with his customary precision

and sincerity, "that is

capable of expressing

feelings in a manner which

moved me personally and made

me aware of how it

approached music", money was

no object. When he took up

his post, a solution was

found that had a direct

relationship to the social

needs of his orchestra and

called upon guest conductors

and soloists to show the

same degree of solidarity

with musicians whose social

status was far lower than

that of their colleagues in

west German orchestras.

Sinopoli was

fully committed to his work

in Dresden. He conducted

some 140 symphony concerts

in his home concert hall,

gave more than 210 concerts

with the Staatskapelle in

Europe, North America and

the Far East, stood in the

orchestra pit of the

Semperoper for performances

of Parsifal, Elektra, Salome

and a new production of Die

Frau ohne Schatten and

conducted the Staatskapelle

in live and studio

recordings of seventy or

more works ranging from

overture to symphony, from

song cycle to opera and

oratorio. The high

expectations placed in him

following the expansion of

his activities in 2003 as

General Music Director of

the Sachsische Staatsoper of

Dresden were left

unfulfilled by his sudden

death.

Richard

Strauss and Gustav Mahler

occupied central positions

in Giuseppe Sinopoli`s

repertoire. Strauss had

given him his first

acquaintance with the

Staatskapelle, after he had

subjected himself to radical

household economies as a

student in Vienna in order

to acquire the Karl Böhm

recording of Elektra; he

soon came to the conclusion

"that Strauss was only to be

heard as they had done it".

From the start he included

Strauss in his programmes in

Dresden, where he could

build on a performing

tradition lasting over a

century. This is his

explanation of what he

valued in this and where he

linked to it: "In the works

of Richard Strauss, the

orchestra proves that its

strengths lie not in its

fortissimo but in the

lightness with which it

makes music, in the

transparency that produces

almost an art nouveau sound,

recalling the painting of

Gustav Klimt." It was easy

enough, he said, to play

Elektra loudly; any

orchestra could do that.

"But this scintillating

lightness of the

Clytemnestra monologue is

something - though I love

the Viennese dearly - which

I have only encountered in

Dresden, or the warm,

blossoming sound upon

recognition of Orestes -

that shows the true power,

the unique sound of this

orchestra." He also referred

to the songfulness of the

Dresden orchestra's playing,

shaped by centuries of close

association between

instrumental and vocal art

in the history of the "State

Chapel" ensemble: "I see in

this another reason why this

orchestra was Richard

Strauss's great love.

Strauss was the only

composer in the past 100

years who could offer true

songfulness, an exceptional

cantabilità. And in Dresden

he experienced a wonderful

union of this songfulness

with the lightness of

orchestral sound that I

spoke of earlier - this was

and is unique."

Gustav Mahler enjoys no

performing tradition with

the Staatskapelle comparable

to that of Strauss. His

scores have always had a

harder road to acceptance by

musicians - and not in

Dresden alone - than the

undoubtedly more accessible

works of his colleague, who

continued living and working

in their midst.

Nevertheless, the "RoyaI

Court Orchestra” was one of

the few ensembles at the

turn from the 19th to the

20th century that was

willing to take on the hotly

contested works of Mahler.

Ernst von Schuch, a friend

of the composer, programmed

the First, Second (twice),

Fourth, Fifth and Sixth

Symphonies in Dresden

between 1897 and 1907. (A

letter from Mahler, director

of the Vienna Hofoper, to

his Dresden colleague Schuch

reads in part: "Many thanks,

dear friend, for your

generous interest in my work

and for your active and so

very successful advocacy of

my humble self as for all

that is new.") The plans of

Fritz Busch constantly

encompassed Mahler, until

his works were outlawed in

the "thousand-year Reich".

After the Second World War,

Joseph Keilberth and

KurtSanderling enriched the

Mahler tradition; in the

1970s and 1980s he was

regularly, but by no means

systematically, performed.

Giuseppe Sinopoli first

tackled Mahler in his fourth

season as chief conductor -

deliberately so late,

because in this specific

case, one that was very dear

to his heart, he wished to

be quite sure of the

artistic resources and loyal

support of his orchestra.

From the qualities described

above which he considered so

typical of the Strauss

performing practice of his

orchestra, he foresaw

positive benefits for his

readings of Mahler. He began

in 1996 with Das Lied von

der Erde, following with

other songs for orchestra

and with the Third, Ninth,

Fourth, Fifth and (only a

few months before his death)

the Sixth Symphony; the

Second, which he had

programmed for May 2001, was

played in memory of him.

Both the works themselves -

Mahler's last symphony and

Strauss`s tone poem - and

the performances of them,

transferred to this CD from

live recordings, have direct

biographical links to

Giuseppe Sinopoli. His April

1997 reading of Gustav

Mahler's Ninth was without

doubt overshadowed by the

death of his father the

previous year. Sinopoli was

on an extended tour of North

America with the

Staatskapelle, well aware

that his father was so sick

that he might hear the worst

any day. His concert

programmes included works

like Ein Heldenleben, the

"Alpine" Symphony and

Bruckner's Fourth Symphony,

alongside works like the

Metamorphosen, the Prelude

and Liebestod from Tristan

und Isolde, the Adagio from

Mahler's Tenth Symphony and

Tchaikovsky's Sixth - a

situation that was as

musically challenging as it

was humanly demanding. On

the evening of the last

concert, in Mexico City,

came the news that his

father's condition was

highly critical. When

Sinopoli arrived home, his

father was no longer alive -

he had come a few hours too

late.We talked about death

many times, and his close

acquaintance with the end of

life arose above all from

his comprehensive knowledge

of the Egyptian rites of the

dead, with which he was

thoroughly familiar from his

archaeological studies. It

was palpable: for him and

for those around him, the

phenomenon had evidently

till now had no relevance;

he simply did not let it

touch him. All the more

elemental, then, was the

force with which it now

struck him, plunging him

into a deep inner crisis and

a long-drawnout personal

engagement with the "last

things". It was inevitable:

a performance of the Mahler

symphony concerning the

"departure from the world,

from life" at that time must

be strongly influenced by

these experiences. He had

noted in 1995: "Music is

always the expression of a

human condition. It says

something human, testifies

to the involvement of a

composer in the world around

him. And it is such messages

that I will deliver -

musical food for thought,

that triggers a process of

change in the listener. What

makes a good interpretation

for me is not everything

being right - intonation,

ensemble playing,

articulation - but when it

says something to me, when

it makes me think. And I

would give everything for

that, even if it costs me

physically..."

The performance of "Death

and Transfiguration" early

in January 2001 seemed to

inaugurate the final phase

of Giuseppe Sinopoli`s life;

there is reason to believe

that he entered it

consciously and with a

certain degree of

premonition. The recording

of this tone poem, which he

often played with the

Staatskapelle - both at home

and on tour - seems in its

very nature to offer a clear

and compelling sign of this.

In February 2001 he

conducted Verdi's Requiem in

the Semperoper on the day

commemorating the bombing of

Dresden, and on his

initiative the entire

proceeds from the resultant

CD were contributed by all

its participants to the

rebuilding of the

Frauenkirche. After the

performance we went to the

Frauenkirche building site

and, lighting a candle and

pointing to it, he very

quietly and sincerely

referred to this symbol of a

fulfilling life: while it

sheds light and warmth, he

said, it is consumed. In his

last concert with the

Staatskapelle on April 8 and

9, 2001, he played

Schumann's First Symphony.

While rehearsing the second

movement he told his

musicians he would like

them, if he should die and

they were still associated

with one another, to play

him this Larghetto. (They

did so.) Finally the last

two days in Berlin: on April

19, till two the next

morning, he listened to his

final Dresden studio

recording, Strauss`s Ariadne

auf Naxos. He had promised

opera director Götz

Friedrich the performance of

Aida in the Deutsche Oper on

April 20, 2001, as a gesture

of reconciliation after a

deep-seated conflict. He

honoured his promise even

after the death of Friedrich

in December 2000, conducting

the performance in his

memory. Referring to the

choice of opera, he wrote on

a slip inserted in the

programme: "Maybe it was

fate that directed us to

that wonderful passage that

closes the opera: 'O terra

addio, addio oh valle di

pianti, sogno di gaudio che

in dolor svani' (oh world

farewell, farewell, o vale

of tears, dream ofjoy that

expires in pain)." And his

last words on this sheet

were to be his own epitaph:

"When Götz accompanies me to

the rostrum today, it will

be as if he is repeating

with clear, persuasive voice

the words given by Sophocles

to Oedipus, who before he

leaves the stage tells the

folk of Colonus: '... You

and this city ... may fate

be kind to you, and in your

prosperity remember me

always with joy when I am

dead.'" - When I took my

leave of Giuseppe Sinopoli

at the end of the interval,

his last words were: "They

are playing wonderfully -

but I am already looking

forward to Aida with my

Dresden people..." A few

minutes later he was gone

from this life.

Eberhard

Steindorf

(Concert

programme manager

to the Staatskapelle for

many years

and personal assistant

to Giuseppe Sinopoli)

Mahler's Ninth Symphony

The first sketches for

Gustav Mahler's Ninth, his

last completed symphony,

date from 1908. The work,

which deals with death, may

have been inspired by the

death of his little daughter

Maria Anna in 1907. Mahler

orchestrated the score in

the summer of 1909 in

Toblach, in the South Tyrol,

starting in June. In

October, he took the new

symphony with him to New

York, where he conducted at

the Met and was artistic

director of the Philharmonic

Society, and the fair copy

he prepared while in America

was complete in April 1910.

The premiere was in 1912,

more than a year after

Mahler's death, and was

given by Bruno Walter in

Vienna.

Strauss`s Tod und

Verklärung

Richard Strauss composed the

tone poem "Death and

Transfiguration" in 1888/89,

between the fiery "Don Juan"

and the merry "Till

Eulenspiegel". The premiere

was given by the composer in

Eisenach in June 1890. The

Dresden Hofkapelle played

the piece for the first time

in 1897 under Ernst von

Schuch; since then it has

been in the permanent

repertoire of the orchestra.

Strauss himself provided a

detailed programme for the

work in 1894 in a letter to

Friedrich von Hausegger: "It

was six years ago that I

first had the idea of

describing the last hour of

a man who had sought the

highest goals, of an artist

in other words, in a tone

poem. The sick man lies

asleep in bed, his breathing

heavy and irregular;

friendly dreams conjure up a

smile on the face of the

wearz sufferer; his sleep

grows lighter, he awakens;

grievous pains begin to

torment him again, the fever

shakes his limbs - when the

attack is over and the pain

subsides, he thinks of his

past life: his childhood

passes before him, his youth

with its endeavours, its

passions and then, as his

pain returns, he sees the

fruit of his life's journey,

the idea, the ideal which he

has sought to realize, to

represent artistically, but

which he couid not complete,

because it was not to be

completed by a human being.

The hour of death

approaches, the soul leaves

the body, to find in eternal

space, completed in glorious

form, that which he could

not complete here below."

Years later he observed,

rejecting all speculation

about personal experience as

the source of his

composition: "‘Tod und

Verklärung' is a pure

fantasy - no experience lies

behind it (I was sick two

years later): a chance

thought like any other,

probably after all the

musical need to write a

piece, after ‘Macbeth’

(begins and ends in C

minor), ‘Don Juan’ (begins

in E major and ends in E

minor), which begins in C

minor and ends in C major!

Qui le sait?" At the same

time, this somewhat

dismissive account is placed

in perspective by the

knowledge that Strauss was

pursuing philosophical

studies at the time he wrote

"Death and Transfiguration"

about Kant`s treatise on the

Swedish natural scientist

and theosophist Swedenborg,

prompting the observation:

"Swedenborg claimed he could

look into heaven and had

seen it as a transfigured

earth, where we continue and

complete the work we have

done hre below. I believe

this."

On August 15, 1972, as part

of the Salzburg Festival,

Karl Böhm, opera and general

music director in Dresden

from 1934 to 1943, conducted

a Staatskapelle concert

comprising Mozart's Symphony

K201 and Mahler's

Kindertotenlieder together

with Tod und Verklärung. In

the middle of a rehearsal of

Strauss's tone poem, the

conductor suddenly broke off

and told the musicians (as

one of them noted at the

time): "Strauss suffered

from tuberculosis in his

youth. The Pschorrs - the

wealthy brewers - made it

possible for him to spend a

year in Egypt, and then he

came back and climbed a

mountain and said: 'If I can

climb this mountain, I am

healthy,` and so he was. And

it was under the impact of

his illness that he wrote

this piece. What his son

told me is extremely

interesting: that he -

maybe, if you are interested

in this, but you are linked

with Strauss after all - 24

hours before his death he

awoke from a period of agony

and said to Bubi (as he was

called, Strauss`s son):

‘Everything I wrote in

"Death and Transfiguration"

is true. The memories of

youth - I have been through

all that - the gate that

opens - the trumpets - and

then the ascent into

eternity.' Well, just

imagine that! Then he

actually added: ‘If I should

ever return to this world, I

have come to the conclusion

I would do nothing

different.' See, if you can

say that at 85, not long

before your death, that

really is the culmination of

your life. There is no more

to be said. That's all true,

what I have just told you -

not a made-up fairy tale.

Believe me..." And the

rehearsal continued.

Eberhard

Steindorf

(Translation:

Janet and

Michael

Berridge)

|

|

|