|

|

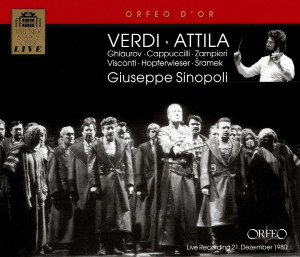

Orfeo

- 2 CDs - C 601- 032 I - (p) 2003

|

|

| Giuseppe

VERDI (1813-1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Attila |

|

109' 26" |

|

| Dramma lirico in

un prologo e tre atti /Libretto:

Temistocle Solera) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

67'

55" |

|

|

1.

Preludio |

3' 17" |

|

|

| PROLOGO |

2.

"Urli, rapine, gemiti, sangue,

stupri, rovine" (Coro)

|

2' 02"

|

|

|

|

3. "Eroi,

levatevi!" (Attila, Coro) |

2' 08" |

|

|

|

4.

"Di vergini straniere" (Attila,

Uldino, Odabella) |

1' 01"

|

|

|

|

5.

"Allor che i forti corrono" (Odabella,

Attila, Coro) |

5' 49" |

|

|

|

6.

"Uldino, a me dinanzi" (Attila,

Ezio) |

7' 58"

|

|

|

|

7.

"Qual notte!" (Coro, Foresto) |

7' 01" |

|

|

|

8.

"Ella in poter del barbaro!" (Foresto,

Coro) |

2' 50" |

|

|

|

9.

"Cessato alfine il turbine, più il

sole brillerà" (Coro, Foresto) |

4' 10" |

|

|

| ATTO PRIMO |

10.

"Liberamente or piangi" (Odabella) |

6' 26" |

|

|

|

11.

"Qual suon di passi!" (Odabella,

Foresto) |

8' 23" |

|

|

|

12.

"Uldino! Uldin!" (Attila,

Uldino) |

1' 49" |

|

|

|

13.

"Mentre gonfiarsi l'anima" (Attila) |

3' 19" |

|

|

|

14.

"Raccapriccio! Che far pensi?" (Uldino,

Attila) |

2' 15" |

|

|

|

15.

"Parla, impone" (Coro, Attila,

Leone) |

4' 08" |

|

|

|

16.

"No!... non è sogno" (Attila,

Uldino, Leone, Odabella, Foresto,

Coro) |

5' 19" |

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

41'

31" |

|

| ATTO

SECONDO |

1.

"Tregua è cogli Unni" (Ezio) |

1' 47" |

|

|

|

2.

"Dagli immortali vertici" (Ezio) |

2' 58" |

|

|

|

3.

"Salute ad Ezio" (Coro, Ezio,

Foresto) |

1' 34" |

|

|

|

4.

"È gettata la mia sorte" (bis) (Ezio) |

4' 40" |

|

|

|

5.

"Del ciel l'immensa volta" (Coro,

Attila, Ezio, Foresto, Odabella,

Uldino) |

8' 18" |

|

|

|

6.

"Si riaccendan le querce d'intorno"

(Attila, Foresto, Odabella, Coro) |

2' 00" |

|

|

|

7.

"Oh, miei prodi!" (Attila,

Odabella, Foresto, Ezio, Uldino,

Coro) |

3' 19" |

|

|

| ATTO TERZO |

8.

"Qui del convegno è il loco" (Foresto,

Uldino) |

2' 52" |

|

|

|

9.

"Che non avrebbe il misero" (Foresto) |

2' 57" |

|

|

|

10.

"Che più s'indugia" (Ezio,

Foresto, Coro, Odabella) |

2' 48" |

|

|

|

11.

"Te sol, te sol quest'anima" (Odabella,

Foresto, Ezio) |

3' 11" |

|

|

|

12.

"Non involarti, seguimi" (Attila,

Odabella, Foresto, Ezio, Coro) |

5' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nicolai GHIAUROV,

ATTILA, re degli Unni |

CHOR DER WIENER

STAATSOPER |

|

| Piero CAPPUCCILLI,

EZIO, generale romano |

Norbert Balatsch, Chorus

master |

|

| Mara ZAMPIERI, ODABELLA,

figlia del signore di Aquileia |

ORCHESTER DER WIENER

STAATSOPER |

|

| Piero VISCONTI,

FORESTO, cavalieri aquileiense |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI

|

|

| Josef HOPFERWIESER,

ULDINO, giovane bretone, schiavo d'Attila |

|

|

| Alfred ŠRAMEK, LEONE,

vecchio romano |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Staatsoper,

Wien (Austria) - 21 dicembre 1980 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Artistic

Supervision

|

|

Gottfried

Kraus |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Gerhard

Lang |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Alfred

Zavrel |

|

|

Digital

Remastering |

|

Ton

Eichinger / Othmar Eichingen,

Gottfried Kraus

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Orfeo | C 601

032 I | LC 8175 | 2 CDs - 67'

55" & 41' 31" | (p) 2003 |

ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Eine

Aufnahme des Österreichischen

Rundfunks ORF.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Attila

Conquers Vienna

Memories of the Attila-Premiere

at the Vienna State Opera on

the 21.12.1980

It was a

premiere that couldn’t have

been more glittering. at

least, that is, from a

musical point of view. As an

event it wrote history

because since then Verdi's

early operas have been seen

in an entirely new light.

If, before this premiere,

one tended to see pieces

like Attila as

nothing more than stations

along the route to the

mastery that Verdi achieved

in such works as Rigoletto,

Il Trovatore, and La

Traiviata, one also

recognised that even in his

early works Verdi was not

limited to a simple

reworking of the

conventional forms of the

Italian opera of the first

half of the nineteenth

century. Instead he used

these forms and forced them

open from the inside

creating a cleared field in

which he would later

construct his outstanding

masterpieces. One fact is

incontrovertible: Only in

his Rigoletto did

Verdi first find a specific

musical sound world for each

of his operas that

corresponded to the

respective subject. This is

not so apparent in the works

of his so-called galley

years, to which Attila

belongs. The work is his

ninth of a total of 28

operas; its successful world

premiere took place in

Venice in 1846 and

performances throughout the

rest of Europe followed soon

afterwards. A glimmer of the

fire that is proof of his

strong character and

superior will to create is

already evident in these

early works. It was Giuseppe

Sinopoli, the man at the

musical helm of the

legendary premiere on the

21st of December 1980 and

concurrently making his

debut at the House on the

Ring, who first brought this

quality to light. In

contrast to many other

conductors who at the best

allow the fire in Verdi's

early works to smoulder,

Sinopoli did his utmost to

set the glow of this music

ablaze in a manner that

perhaps only Thomas

Schippers, who died in 1977,

had done before him in his

recordings of Ernani

and Il Trovatore.

Before this debut

Sinopoli’s name was largely

unknown in Viennese operatic

circles. They had certainly

heard about a sensational Macbeth

premiere at the Deutsche

Oper Berlin a few months

previously. Beyond they knew

only that the venetian

conductor and composer, born

in 1946, had graduated in

the famous conducting class

of Hans Swarowsky. He was

seen to belong primarily to

the realm of the musical

avantgarde. On entering the

orchestra pit he was given a

friendly, but cautious

reception. However, it was

clear after a few bars of

the prelude that the events

of the evening would touch

on the extraordinary.

Sinopoli spurred the

orchestra to an intensity

that the Viennese had deemed

impossible for this sort of

music. When he reclaimed the

podium after the interval

the enthusiastic ovation

corresponded to his

achievenebt. At the end of

the performance his

appearance in front of the

curtain brought on further

ovations and storms of

excitement. There habe been

few such triumphant debuts

in this house. To answer the

question of how exactly

Sinopoli achieved this

rehabilitation of Verdi's

early works, one must first

turn to his treatmente of

rhythm. Sinopoli cracked

open the apparent uniformity

of the accompanying

instrumental figures, so

typical of the Italian opera

of that period, over which

Verdi spins his heavenly

melodies. He dynamically

sharpened and accentuated

these stereotypical

accompanying figures,

achieving a pressing urgency

and sometimes an almost

aggressive power. In this

way rhythm became tonecolour

and it was this that imbued

the evening with its

enormous tensio,

Verdi made his first forays

into musical nature painting

in Attila: the

second scene in the prologue

presents a thunderstorm that

soon transforms into a

sunrise. In the banquet

scene of the second act a

wild tempest rages, an

external symbol of the

apparently out of control

situation in which Foresto

offers Attila a poisoned

cup. Foresto's lover,

Odabella unexpectedly warns

Attila against the cup

although she too is

contemplating the death of

the Hun king. But Verdi also

begins to use more intimate

portraits of nature in his

music, for example

Odabella's Romanza Oh!

nel fuggente nuvolo.

The moonlit night in tghis

scene is expressed in a

filigreelike web of sound in

which an English horn keeps

the voice company,

surrounded by the gentle

accompaniment of the flute,

harp, cellos and basses. It

was one of Sinopoli's

strengths that he made this

sort of instrumental finesse

crystal clear to the public

and gave it as much

attention as the voices.

Two years after this

spectacular State Opera

debut I had the opportunity

to take a peep into Giuseppe

Sinopoli's workshop. As a

student of the

Musikhochschule in Vienna I

invited him to give a

lecture for which he

requested no payment, but

instead asked me to assist

him with the preparation of

the orchestral parts for

Verdi's Nabucco. I

was amazed by the many

additions that Sinopoli had

made to the printed score.

Directions for bowing,

rhythmic and or dynamic

accents were marked over

almost every note. All

specifications that, when

translated into sound, gave

rise to the fiery, vibrant

playing that made Sinopoli's

Verdi interpretations so

unique. Nothing was left to

chance, Sinopoli had not

only made an exhaustive

study of the sources (the

autographed manuscripts and

the first editions), but had

also won insight by careful

comparison with Verdi's

other early works. In places

where the composer's

specific intentions remained

unclear Sinopoli went in

search of a similar

dramaturgical or musical

moment in another opera that

might offer more specific

directions, to gain insight

into Verdi's intentions.

This method could also be

applied to Attila,

which was composed for years

later.

The premiere on the 21st of

December 1980 - Attila

was being performed for the

first time in the House on

the Ring, prior to this the

work had only four

performances at the

Kärntnertortheatre in 1851 -

was not only sensational

because of Sinopoli. The

cast kept up with the high

demands made on them and

presented the public with a

festival of singing, with

Nicolai Ghiaurov in the

title role. His fiery bass

gave him the high level of

refinement required to

portray the complete

character in this role. In

Ghiaurov's interpretation

the bold, martial conqueror

was as visible as the tender

loving man. Take for example

the final scene where he

greets Odabella with a

gentle gesture while she

holds a bared sword, ready

to avenge her father's

death. Odabella is probably

the most energetic of all

Verdi heroines, even her

first entrance requires her

to ascend to a high C in

wide leaps, only to descend

immediately to a low

B-natural in a coloratura

cascade. Not even Attila can

resist this woman's

passionately wild

determination though he and

his troops hold the world in

fear. The role provided a

showcase for Mara Zampieri,

who was particularly beloved

in Vienna. It would be

difficult to withstands the

fascination of her highly

expressive singing and

dauntless attitude to risks.

Mara zampieri was volcanic.

She had an attack that few

other singers could rival,

but she could also lose

herself in ethereal fields

where she enjoyed her few

contemplative passages to

the full and with a high

degree of vocal and

intellectual intensity.

On the occasion of the

Vienna premiere in 1851 the

critic Eduard Hanslick

termed Verdi's Attila

the culmination of the

cabaletta style. In

this opera the cabalettas do

indeed follow one another in

quick succession, the most

famous is that of Ezio. When

bidden by the weak Emperor

Valentinian to make a

dishonourable truce with

Attila, the Roman general

decides to act

independently. Piero

Cappuccilli, then at the

zenith of his art, sang Ezio

in the Vienna State Opera

production. He crowned the

stretta with a high B-flat

that is most unusual for a

baritone. The public

jubilation was so

overwhelming that

Cappuccilli was forced to

repeat the stretta, not only

at the premiere, but also at

almost every repeat

performance in which he sang

Ezio. This in its turn

incited some comment in the

press. One piece, signed

Roger that appeared in the Volksstimme

complained about the lengthy

interruption of the

performance. Clemens

Höslinger in his turn,

reported primeval noises

in the Neue Zeit and claimed

that the riotous scenes

played out at Attila present

themselves as a clear case

of idiocy. Such

remarks prove the imperfect

knowledge of the Viennese

opera going public, which

allows its self to be caried

along by both enthusiastic

approval and criticism. On

this opening night the choir

leader Norbert Balatsch met

with misplaced disapproval

because he was the first man

in a dark suit to take a bow

on stage. In fact the public

animosity was not directed

at him, but rather at the

designer Ulisse Santicchi

and the director, Giulio

Chazalettes, a Strehler

student. The critics also

shredded the creative output

of these two men. In the Presse

Franz Endler claimed that Mr.

Chazalettes arranged the

scene with a routine hand,

the choir moved like a

relic of a bygone era that

we no longer know. The

protagonist stand aound

like trees on the stage

unless they are

arbitrarily enganging in a

game of puss in the corner

that also fails to make

sense. To disguise this

Mr. Santiccho plunges his

scenes into a pleasant

darkness in which the

protagonist currently

singing is mildly

illuminated by spotlight.

In the Süddeutsche

Zeitung Otto F. Beer

wrote: Giulio

Chazalettes was

responsible for the

production, or rather the

lack thereof. Ulisse

Santicchi's setting

supplies an Italy in the

grip of a Mediterranean

low pressure cell,

complete with bad weather

and endless grey, The

chorus and soloists stand

around helplessly in

the middle of this Hun war

and when a light

occasionally blinks

through the darkness of

the night one is left

unsure of whether it is a

flash of lightning or the

result of a loose

connection.

The assessment of the

musical side of the evening

was very different.

Karlheinz Roschitz reported

on the triumph of the

star singers in the Kronen

Zeitung, Walter Beyer

of the Oberösterreichische

Nachrichten described

the opulent casting

adding that Nicolai

Ghiaurov in the title role

was streets ahead of his

colleagues. The best Piero

Cappuccilli that has ever

been brought the house

down with his stretta that

scaled the heights of the

high B-flat and he was

promptly forced to repeat

it. All the while, Mara

Zampieri was waiting with

her giant vocal resources

and almost vibrato free

high register. The

majority of the press

attributed Attila's

raging conquest of Vienna to

the conductor. Klaus Geitel

of Die Welt was of

the opinion that: As the

leader of the lively,

sparkling and enterprising

Vienna Philharmonic

orchestra he

(Sinopoli) brought a

Verdi to light that could

not have been more fiery,

nor differentiated. The

briskness, the joy in risk

taking that belong to

early Verdi (he was only

33 when he wrote Attila),

the explosions of

temperament, the

robustness and the rigour

all lend the traditional

formal arrangement an

overwhelming newness: a

virility that was not

suited to the delicate

opera music of his

predecessors. In the Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung

Hilde Spiel, the Grande Dame

of Austrian critics came to

the conclusion that the

true musical event of the

evening was the appearance

of Giuseppe Sinopoli,

until now primarily known

as an avant-garde

composer, on the

conductors podium. In

terms of tension and

precision, in terms of

voluptuous brio he is no

way inferior to the best

Italian conductors od

today, it seems he has

been preordained to follow

Abbado.

Hilde Spiel's prophecy

should have held true, with

this production of Attila

Giuseppe Sinopoli had played

himself into the highest

league of conductors. He led

further new productions at

the Vienna State Opera in

the following years. These

included Verdi's Macbeth,

Puccini's Manon Lescaut

and Strauss' Die Frau

ohne Schatten along

with a new version of

Wagner's Tannhäuser.

Further projects were

planned, but the sudden

death of the conductor - he

collapsed during a

performance of Verdi's Aida

in April 2001 at the

Deutsche Oper Berlin - put a

close to his work at

the Vienna State Opera all

too soon.

Peter Blaha

(Translation:

Kirsten Dawes)

|

|

|