|

|

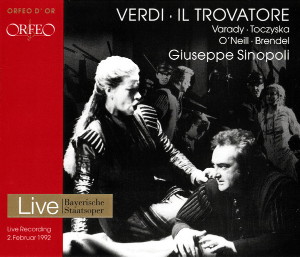

Orfeo

- 2 CDs - C 582- 032 I - (p) 2003

|

|

| Giuseppe

VERDI (1813-1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Il Trovatore |

|

139' 28" |

|

| Dramma lirico in

quattro parti (Libretto:

Salvatore Cammarano) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

70'

38" |

|

| PARTE PRIMA |

|

Il Duello |

|

|

|

|

No.

1 - Introduzione |

1.

"All'erta! all'erta!" (Ferrando,

Coro) |

3' 01" |

|

|

|

|

2.

"Di due figli vivea padre beato" (Ferrando,

Coro)

|

8' 00"

|

|

|

|

No.

2 - Scena e Cavatina |

3. "Che più

t'arresti?" (Ines, Leonora) |

2' 26" |

|

|

|

|

4.

"Tacea la notte placida" (Leonora) |

6' 10"

|

|

|

|

No.

3 - Scena, Romanza e Terzetto |

5.

"Tacea la notte!" (Conte) |

1' 57" |

|

|

|

|

6.

"Deserto sulla terra" (Manrico,

Conte, Leonora) |

6' 29"

|

|

|

| PARTE

SECONDA |

|

La

Gitana |

|

|

|

|

No.

4 - Coro di Zingari e Canzone |

7.

"Vedi! Le fosche notturne spoglie" (Coro) |

2' 46" |

|

|

|

|

8.

"Stride la vampa!" (Azucena,

Coro, Un vecchio zingaro) |

4' 59" |

|

|

|

No.

5 - Scena e Racconto |

9.

"Soli or siamo!" (Manrico,

Azucena) |

5' 57" |

|

|

|

No.

6 - Scena e Duetto |

10.

"Non son tuo figlio?" (Manrico,

Azucena) |

5' 45" |

|

|

|

|

11.

"L'usato messo Ruiz invia!" (Manrico,

Un messo, Azucena) |

4' 11" |

|

|

|

No.

7 - Scena e Aria |

12.

"Tutto è deseerto" (Conte,

Ferrando) |

1' 28" |

|

|

|

|

13.

"Il balen del suo sorriso" (Conte) |

3' 44" |

|

|

|

|

14.

"Qual suono!... oh ciel!" (Conte,

Ferrando, Coro) |

6' 00" |

|

|

|

No.

8 - Finale secondo |

15.

"Perché piangete?" (Leonora,

Ines, Conte, Coro) |

1' 49" |

|

|

|

|

16.

"E deggio e posso crederlo?" (Leonora,

Conte, Manrico, Ferrando, Ines,

Coro, Ruiz) |

5' 33" |

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

65'

50" |

|

| PARTE TERZA |

|

Il

figlio della Zingara |

|

|

|

|

No.

9 - Coro d'Introduzione |

1.

"Or co' dadi, ma fra poco" (Coro,

Ferrando) |

4' 33" |

|

|

|

No.

10 - Scena e Terzetto |

2.

"In braccio al mio rival!" (Conte,

Ferrando, Coro, Azucena) |

2' 19" |

|

|

|

|

3.

"Giorni poveri vivea" (Azucena,

Ferrando, Conte, Coro) |

6' 17" |

|

|

|

No.

11 - Scena ed Aria |

4.

"Quale d'armi fragor poc'anzi

intesi?" (Leonora, Manrico) |

2' 06" |

|

|

|

|

5.

"Ah sì, ben mio, coll'essere io tuo"

(Manrico) |

3' 17" |

|

|

|

|

6.

"L'onda de' suoni mistici" (Leonora,

Manrico, Ruiz) |

2' 04" |

|

|

|

|

7.

"Di quella pira" (Manrico,

Leonora, Ruiz, Coro) |

2' 34" |

|

|

| PARTE QUARTA |

|

Il

Supplizio

|

|

|

|

|

No.

12 - Scena, Aria e Miserere |

8.

"Siam giunti: ecco la torre" (Ruiz,

Leonora) |

2' 59" |

|

|

|

|

9.

"D'amor sull'ali rosee" (Leonora) |

4' 11" |

|

|

|

|

10.

"Miserere d'un'alma già vicina" (Coro,

Leonora, Manrico) |

8' 15" |

|

|

|

No.

13 - Scena e Duetto |

11.

"Udiste? Come albeggi" (Conte,

Leonora) |

5' 10" |

|

|

|

|

12.

"Colui vivrà. - Vivrà!... Contende

il giubilo" (Conte, Leonora) |

2' 44" |

|

|

|

No.

14 - Finale ultimo |

13.

"Madre, non dormi?" (Manrico,

Azucena) |

5' 17" |

|

|

|

|

14.

"Sì, la stanchezza m'opprime" (Azucena,

Manrico) |

3' 40" |

|

|

|

|

15.

"Che!... non m'inganna quel fioco

lume?" (Manrico, Leonora,

Azucena) |

4' 26" |

|

|

|

|

16.

"Ti scosta! - Non respingermi..." (Manrico,

Leonora, Conte, Azucena) |

5' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Julia VARADY, LEONORA |

CHOR DER BAYERISCHEN

STAATSOPER |

|

| Stefania TOCZYSKA,

AZUCENA |

Eduard Asimont, Chorus

master |

|

| Dennis O'NEILL,

MANRICO |

BAYERISCHES

STAATSORCHESTER |

|

| Wolfgang BRENDEL,

IL CONTE DI LUNA |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI

|

|

| Harry DWORCHAK,

FERRANDO |

|

|

| Georgina von BENZA,

INES |

|

|

| Jan VACIK, RUIZ |

|

|

| Friedrich LENZ,

UN MESSO |

|

|

| Hermann SAPELL,

UN VECCHIO ZINGARO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Staatsoper,

Munich (Germania) - 2 febbraio

1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Digital

Remastering |

|

Ton

Eichinger / Othmar Eichingen,

Gottfried Kraus

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Orfeo | C 582

032 I | LC 8175 | 2 CDs - 70'

38" & 65' 50" | (p) 2003 |

DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Eine

Aufnahme des Bayerischen

Staatsoper.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

About the

Present Live Document

The premiere of Trovatore

on 2 February 1992 was not

recorded by Bavarian Radio -

as is otherwise usual in the

Edition Bavarian State

Opera Live - but by

the Munich National Theatre,

in their own production.

This publication is based on

the archive tape thus

obtained from them.

Unfortunately, several

errors and distortions were

found on it that could be

restored with the help of

digital technology. Only in

the 7th Scene (CD2, track

10), the distortions could

not be eliminated completely

without damaging the tape.

The extraordinary artistic

auality moved ORFEO

International to publish

this document nonetheless.

Listeners will surely have

understanding for this

decision, considering the

density and vitality of this

unrepeatable operatic

performance.

Gripping

Vitality and Emotional

Density

The unsurpassed

level of vocal excellence

required - four-fold - by

Giuseppe Verdi’s Il

Trovatore has been

most precisely captured in

an ironically tinged

superlative attributed to

Enrico Caruso: "A

performance of Trovatore

is very simple - one just

needs the four best

singers in the world!"

Nonetheless, hardly an opera

house in the world has

hesitated to stage the

centrepiece of Verdi’s Trilogia

popolare - flanked as it is

by Rigoletto and La

Traviata. No wonder

that Il Trovatore

counts amongst the ten most

frequently performed operas

in the world. The Munich

Court and State Opera, too,

has repeatedly presented new

productions of the work

since its Munich premiere in

1859, most recently on 2

February 1992 - a production

by Luca Ronconi with scenery

by Margherita Palli (set

design) and Gabriella

Pescucci (costumes),

conducted by Giuseppe

Sinopoli. The

internationally assembled

team of singers is an

indication of two things:

firstly, that hardly a

first-rate Verdi singer has

hailed from Italy during the

past decade, and secondly

that this deficit could be

thoroughly compensated by

equally fine vocal talents

from other nations.

In the case of the

Leonora interpreter Julia

Varady of Rumanian-Hungarian

origin, one would even have

to look very far back in the

genealogy of great italian

role predecessors in order

to discover comparable

vocal-theatrical excellence.

Julia Varady's fascinating

achievement in this role on

that evening also gave the

press occasion for

uninhibited praise: Joachim

Kaiser enthuses over the "wonder

Varady" in the Süddeutsche

Zeitung, singing

praises to her "all

outshining freedom of

expression." The

critics unanimously fell

upon their knees before the

soprano: characteristics

such as "entrancing,"

and "uniquely beautiful"

were overtrumped by others

which called Varady's art a

"singular richness,"

attesting her to be "captivating

in the tones of tenderness

and devotion, ravishing in

the fire of passion."

These are superlatives, to

be sure, but they are

justified. For the soprano,

who has been instrumental in

establishing the high vocal

standard of the Bavarian

State Opera for nearly the

past two decades, was at the

summit of her vocal

possibilities at that time.

Especially in Verdi roles

such as Aida, Violetta (La

Traviata), Abigaille (Nabucco),

Leonora (La forza del

destino), Elisabetta (Don

Carlo) and Desdemona (Otello),

she made many Munich opera

performances into events of

exceptional vocal rank. The

fact that she is not

documented in the CD

catalogue in any of these

roles is a great pity - an

unpardonable omission on the

part of record companies. It

is a deficit which - with

the issue of this live

recording - can be remedied,

in at least one case. Like

her great model Maria

Callas, Julia Varady counts

amongst those singers who do

not merely wish to please

through velvety euphony,

flawless polish or sheer

purity of tone. Her unique

vocal-theatrical imagination

contains much more - an

infallible dramatic instinct

and the ability to master

the scene, both acoustically

and visually. Both of these

are qualities that meant

much more to Verdi than an

impersonal, beautiful voice

or the pleasingly perfect

reproduction of the notes.

Once, when a singer was

recommended to the composer,

he was completely

uninterested in her

brilliant vocal qualities,

posing only this question: "And

does she have dramatic

passion in her voice?"

The name and career of

the Welshborn Dennis

O’Neill, who simultaneously

gave both his first Munich

performance and his role

debut as Manrico, are

closely connected to the

operas of Giuseppe Verdi. In

over a dozen roles of this

composer he has attained

international acclaim as a

versatile tenore spinto,

as the singer of a vocal

range and type that is only

gradually formed in Verdi’s

oeuvre with the figures of

Ernani and Rodolfo (Luisa

Miller), attaining

full development with the

role of Manrico and

continuing with Riccardo (Un

ballo in maschera),

Alvaro (La forza del

destino), Don Carlo

and Radames (Aida).

The manner of utterance of

Verdi’s tenore spinto

is considerably different

from the lyrical-elegiac and

coloratura-saturated vocal

style of the tenore di

grazia in the bel

canto era of Rossini,

Bellini and Donizetti. This

difference is manifested in

straight-lined realism and

psychological credibility,

dramatic density and

emotional presence -

characteristics that have

coined the term accento

Verdiano. As far as

the particular affinity of

the Welsh, of all people,

for Italian music and opera

is concerned, not only

renowned singer-colleagues

such as Margaret Price,

Stuart Burrows and Bryn

Terfel are prominent

witnesses of Dennis O’Neill.

George Bernard Shaw, too,

recognised the southern

component of his Welsh

fellow-countrymen: "The

Welsh are Italians in the

rain," as he put it.

It may be that therein lies

the explanation for

O'Neill’s success as an

Italian tenor. The critics

also praised his portrayal

of Manrico as containing "tenor

power of radiance," "lyrical

mellowness," "security

in the high notes and the

verve of performance."

Amongst the protagonist

roles in Trovatore,

Azucena is from the very

outset the central

personality in the piece who

most ispired and interested

Verdi. Only later did the

composer decide to upgrade

Leonora from a comprimaria

to a female figure of equal

rank. With Azucena, the alto

voice gains an equal

function alongside soprano,

tenor and baritone in the

importance of voval ranges

for the first time in

Verdi's work. Thanks to her

dual function as perpetrator

and victim, Azucena is

a bizarrely iridescent

character, reflected not

only in her vacillation

between real perception and

hallucinatory memory but

also finding singing

expression in the richness

of contrast in her vocal

style. This is a role,

therefore which represents a

stimulating, if thoroughly

ticklish challenge for any

mezzosoprano or alto. The

Polish singer Stefania

Toczyska enjoyed great

success in Munich barely a

decade earlier as Carmen.

Not only do the relatively

few mezzo and alto roles

composed by Verdi occupy a

place in her very broad

repertoire - Ulrica (Un

ballo in maschera),

Eboli (Don Carlo),

Preziosilla (La forza del

destino), Amneris (Aida)

- but also numerous roles in

this vocal range in bel

canto operas as well

as in works of French and

Russian composers. In the

premiere of Trovatore,

after initial reserve,

Stefania Toczyska rose to a

vehemently superlative vocal

achievement. The critics

especially pointed out the "seductively

soft, dark tone of her

mezzo voice," her "ample

volume and dramatic

power," her "polished

vocal technique, her

balance in the high and

low ranges" and her "great

vocal presence."

If there is a vocal range

most closely bound with

Verdi's music-theatrical

intentions and production,

most congenialy

corresponding to his demand

for dramatic truth as a

vocal medium, then it is the

baritone. The reasons for

this lie in the "natural"

timbre of the baritone and

its proximity to the

"normal" male speaking

voice. While Verdi more

strictly reained the

fundamental characteristics

of other vocal ranges, he

developed the baritone voice

in a completely autonomous

direction; indeed, he can be

consiered the actual

"inventor" of this vocal

range in its current,

present-day manifestation.

Not only did he drive the

baritone to higher top-notes

than Bellini and Donizetti

had required before him, but

raised the entire general

tessitura, calling for

extended passages in a high

or very high range as in the

Aria of Conte di Luna Il

balen del suo sorriso

starting with L'amor,

l'amore ond'ardo. In

this manner he created a

voice located between bass

and tenor, closer to the

tenor range, in fact. Due to

their complexity of

character, expressive

variety and contrary

natures, as well as their

highly strung emotional

intensity, the figures upon

whom Verdi conferred his

baritone require a very

special interpretative

flexibility, an almost

tenorlike overtrumping

quality as well as soft,

tender lyricism. The common

denominator existing between

virtually all the role

configurations of the Verdi

baritone is its function as

the antagonist to the hero,

i.e. the tenor in general.

This is usually a

father-like personality

(Simon Boccanegra,

Rigoletto, Miller in Luisa

Miller, Germont in La

Traviata, Montfort in

Les Vêpres Siciliennes,

Amonasro in Aida) or

an amorous rival (Carlo in Ernani,

Gusmano in Alzira,

Francesco Moor in I

masnadieri, Seid in Il

corsaro, Rolando in La

battaglia di Legnano,

Renato in Un ballo in

maschera, Luna) -

roles which, to a large

extent, can be identified

with Wolfgang Brendel. It is

by no means purely by chance

that Verdi occupies a

central position in the

broad repertoire of the

Munichborn singer. And since

1971, Brendel has attained

an important reputation in

Munich, then in the entire

world - also with

Verdi roles. The Bavarian

State Opera could even

experience him in role

debuts as Germont, Simon

Boccanegra, Renato, Luna,

Don Carlo in La forza

del destino and Posa

in Don Carlo.

Brendel could already be

heards as Luna in the

earlier 1973 Trovatore

production of Ernst

Poettgen. He then took over

the role as Kostas

Paskalis's successor; this

time, he was himself the

first choice for the

premiere. Whoever may have

experienced Brendel in the

1970s as a young lyric

baritone reservedly and

almost respectfully

approaching this task, was

astonished to note what an

enormous developmental leap

to a dramatic Verdi

interpreter he has succeeded

in making seince then. The

critics, too, were unanimous

in emphasising his "mighty

overtrumping whilst

preserving the mellowness

of his velvety baritone,"

his "powerful, softly

masculine timbre" and

his "penetrating power,

effortlessly drowning out

the orchestra."

If Italian singers

were missing in this

premiere of Trovatore

- by no means to its

detriment - the genuinely

Italian component came into

play through the conductor,

Giuseppe Sinopoli

(1946-2001). As a conducting

composer, the Swarowsky

pupil began his career on

the podium under the heading

of "Verdi." Still giving

priority to his own musical

production during the 1970s,

he started his international

conducting career from 1980

onwards with highly

acclaimed productions of Macbeth

in Berlin and Attila

in Vienna (ORFEO C 601 032

I). The 1981 Munich premiere

of his first opera Lou

Salomé which he

himself conducted lies on

the temporal turning point

of this transition. If there

was no lack of critical

voices in the appraisal of

Sinopoli's work with the

orchestra - above all in

regard to the

"craftsmanship" in his

conducting ability - his

unrelenting struggle to

achieve source-critical

thoroughness and his

meticulous striving towatds

absolute authenticity are

beyond question. One cannot

dispute the seriousness of

the musical activity of a

conductor who shut himself

in the archives of Ricordi

publishers all day in order

to be certain of the

original versions of Verdi's

score manuscripts. He

especially wanted the early

Verdi to receive the just

recognition that is his due,

which is not the same thing

as dry fidelity to the

original. One could

summarise his musical

thinking and aspiration as a

combination of subtlety,

precision and ardent

passion, a combination of italianità

and intellectuality. His

special interest was in

those aspects which were

unjustly misunderstood and

neglected, such as the

recitative. He did not

regard it as merely a

necessary, dry transition

from aria to aria, but

rather as important,

plot-carrying action music.

Another aspect was the

"M-tata" ehythms - all too

often undervalued as being

too simple and nechanistic.

Due to these, Verdi was long

decried in Germany as being

a "barrel-organ composer."

Sinopoli knew how to gain a

vibrant, lively pulse-beat

out of these rhythms. The

fact that "animated

(the Bavarian State

Orchestra) with

fine-nerved accuracy,

dramatic impulse and

springing, rhythmic

buoyancy to achieve an

emphatic force of speech"

was as much emphasised in

the reviews as was his

ability to "form

glass-clear yet breathing,

living lines, to gain

illuminated tone colours

with the utmost care

whilst demonstrating a

breathtakingly delicate,

deeply heard agogic sense

along with this." To

summarize briefly: "Giusepe

Sinopoli perfectly unites

artistic refinement and a

folkloristic quality

reminiscent of the country

fair."

Sinopoli's

music-making energetically

contradicted those despisers

of this score who regarded Trovatore

as Verdi's reversion back to

the vulgarity of the early

works - a vulgarity he had

overcome with Rigoletto.

It is indeed true that Verdi

originally wanted to

continue the advanced

compositional manner found

in Rigoletto in the

direction of a loosening of

the traditional number

scheme and an upgrading of

the recitative. With the

less than original libretto

of Salvatore Cammarano,

however, he saw himself

pushed back onto the old

rails. Verdi himself finally

recognised that the crude

and fantastic dramaturgy of

the literary model, García

Gutiérrez's drama El

trovador, could best

be structured by means of

the conventional number

principle. The score of Trovatore

is made up almost

exclusively of closed single

pieces - arias, duets, terzetti

and choruses with only one

grand finale. The plot thus

develops as a kaleidoscopic

sequence of pictorial

snapshots. The individual

picture is the actual formal

unit and basis of the

dramaturgical construction,

underlying a libretto built

structly geometrically. The

four parts are in turn

divided into two independent

individual pictures, of

which the second is always

much more extensive than the

first. This impression of an

isolated picture sequence is

strengthened by the fact

that Verdi, for the most

part, dispenses with motivic

development and thematic

expansion. Themes turn up,

are at best repeated and

then replaced by others. Il

Trovatore is therefore

unsurpassed by any other

Verdi opera in melodic

variety. The figures are by

no means characteristic

personalities with

differentiated psychology,

subtle motivation and

consistently growing

maturation and developmental

processes; rather, they

resemble archetypes, which

are so dominated by basic

emotions such as love, hate

jealousy or vengeance that

they have forfeited their

individuality, becoming

purely carriers of passion.

The aesthetic

key-word varietà

applies not only to the

music but also to the style

and structure of the opera

as a whole. This includes

the colour of the subject,

richness in contrast of

personages and actions and

the alternation between

different scenes of action.

In spite of its

predominantly gloomy tone,

with Gypsy and military

camps,manstery, castle and

dungeon, the opera offers a

broad palette of scenes with

a strongly visual radiance.

This is fascinatingly

obvious in the first scene

of the fourth part, perhaps

the scene with the greatest

density of moods in the

entire opera. Here Verdi

develops a refined,

graduated aesthetic of space

and sound with a

unique effect. Following the

painful longing Adagio of

Leonora's aria D'amor

sull'ali rosee, the

scenic space opens up, as it

were, with a monks' choir

intoning a Miserere

without orchestral

accompaniment behind the

stage with only a

death-knell on E-flat

breaking through. Then

begins a funeral march of

Leonora, with a blacl

foundation provided by the

orchestral tutti in

piano-pianissimo. A

sonic spatial effect comes

into being here anew through

the urgent lamenting of the

prisoner Manrico from the

remote dungeon, accompanied

by a solo harp. Finally, in

the coda after the second

verse of the funeral march,

all the sound-layers are

combined and the spatial

distance is gradually

removed. The overwhelming

success of the premiere of Il

Trovatore on 19

January 1853 in the Roman

Teatro Apollo was in no

small measure due to the

scenic suggestive quality of

such tableaux; the

entire final scene had to be

repeated on that occasion.

Within a few years the work

had been performed on nearly

all the important European

stages. The triumphant

performance history of Trovatore

is irrefutable proof that

the often ridiculed muddle

of the plot, appearing to

lack any kind of concise

logic and psychological

probability, can in no way

detract from the gripping

vitality and emotional

density of Verdi's music.

Kurt Malisch

(Translation:

David Babcock)

|

|

|