|

|

DG - 1

CD - 469 527-2 - (p) 2001

|

|

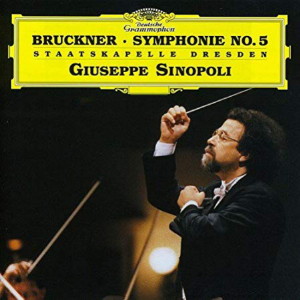

| Anton BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie No. 5

B-dur |

|

76' 37" |

|

| Edition:

Leopold Nowak |

|

|

|

| -

1. Introduction.

Adagio - Allegro |

20' 51" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio- Sehr langsam |

18' 48" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo. Molto vivace

(schnell) - Trio. Im gleichen

Tempo |

13' 30" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale. Adagio - Allegro moderato |

23' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Semperoper,

Dresden (Germania) - marzo 1999 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Arend

Prohmann |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Jürgen

Bulgrin, Wolf-Dieter Karwatky |

|

|

Post-Production |

|

Oliver

Rogalla |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 469 527-2 | LC 0173 |1

CD - 76' 37" | (p) 2001 | DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The February

of 1875, when he began

composing his Fifth

Symphony, found Bruckner

isolated and ill at ease in

Vienna. The city’s

sophisticated atmosphere and

manners little suited him,

he was poorly paid for his

teaching at the

Conservatory, and the Vienna

Philharmonic had dismissed

his Third Symphony as

“unplayable” after a trial

performance. If he

found difficulty in

protecting himself from his

enemies, in particular the

phalanx of critics led by

the powerful Eduard

Hanslick, he also needed

preservation from his

friends; for, in an effort

to win his music acceptance,

some of them set about

revising and rewriting the

symphonies so as to make

them more palatable to the

Viennese audience. Savage

cuts were inflicted, and the

music was reorchestrated,

often in a style closer to

that of Bruckner's

most influential admirer, Richard

Wagner.

Beset with self-doubt,

Bruckner accepted this

interference and was even

persuaded to make revisions

himself. In

well-meaning attempts to get

the music some sort of a

hearing, there were public

performances in two-piano

arrangements; and, indeed,

the only penformance of the

Fifth Symphony that the

composer ever heard was

given in this form, by Franz

Schalk and Franz Zottmann.

Schalk later conducted his

own cut and re-orchestrated

version of the work in Graz

on 9 April 1894, one which

would have appalled Bruckner

even more had he been well

enough to travel to hear it.

The whole history of

Bruckner revisions is a

notoriously complicated one;

suffice it to say that

nowadays the most widely

accepted version of this

symphony (as of others) is

Bruckner's own original, as

recorded here, which he

largely completed in 1876,

making some slight revisions

in 1877-78.

In defence of Bruckner’s

opponents, it may be said

that the symphonies’ originalities

would have seemed the more

confusing to Viennese

audiences that saw

themselves as partakers in a

tradition handed down from

Haydn and Mozart by way of

Beethoven and Schubert to

its current legatee,

Johannes Brahms. Even today,

when he has long been

accepted as a composer of

world stature, Bruckner's

music seems disconcertingly

different from that of his

symphonic forebears. Those

approaching the Fifth

Symphony, for instance, one

of the grandest and most

original of the entire

cycle, will not find a first

movement that gives them two

contrasting themes and then

takes them through

development and finally

recapitulation as, in their

different ways, Bruckner's

predecessors do. He is

concerned more with setting

out and exploiting

contrasted musical gestures.

The Fifth opens on strings

with a trudging bass figure

and soft, mysterious

counterpoint; after a brief

silence, there is a blaze of

sound on wind and brass;

then the tempo speeds up on

strings until a true Allegro

is reached with a new theme

under the high tremolo

strings that are a familiar

Bruckner fingerprint. The

relationships between these

very different musical

gestures only gradually

reveal themselves,

especially as Bruckner takes

his time with modifying them

and disclosing their

kinship.

There is also an

unfamiliarity in Bruckner‘s

use of keys. Few listeners,

as they follow the music,

will consciously concern

themselves with the fact

that Bruckner is making much

play with the engagement

between B flat (the opening

and closing key of the

symphony) and D, the key of

the two central movements.

Yet it is this contest,

waged with particular

subtlety within the first

movement, that gives the

music its particular

flavour; heard perhaps most

immediately as a series of

surprising shifts across

keys as the main thematic

components realign

themselves one with another.

It

remains astonishing music,

but for the listener in

sympathy with Bruckner, it

is his judgement and that of

no opponent or interferer

which is to be trusted.

The slow movement, which

Bruckner began first, is in

a more familiar melodic

vein, with a bleak oboe

theme over pacing triplets,

later a powerful violin

song; and the Scherzo

maintains the classical

balance between a fastmoving

melody, close in spirit to

the Ländler

of Bruckner’s country

origins, and a contrasting

Trio. But Bruckner has not

abandoned the subtle

thematic connections of the

first movement; and when he

comes to the finale, it is

to reaffirm these with a

breathtakingly bold gesture,

invoking Beethoven‘s Ninth

Symphony in his recall of

themes from the previous

movements. Yet whereas

Beethoven reflected upon

these in order to discard

them in favour of “a new

song”, Bruckner gathers his

material together in a

renewed symphonic effort. All his

craft is brought to bear

upon the music - and we

remember that it was a craft

learned inthe organ loft -

so that fugal writing plays

its part, as also, in a

superb climax, does a

chorale on brass, a

tremendous full orchestral

statement of which brings

the symphony home in B flat.

This was the

most powerful symphony

Bruckner had yet written,

and the most puzzling.

Brahms, though personally

courteous to the composer,

could not find it in

himself to be sympathetic

to the music.

Significantly, it was

contemporaries belonging

to a newer movement in

music who rallied to this

master of a form they

themselves had largely

discarded - Hugo

Wolf, fervent in his

writings on Bruckner’s

behalf, Liszt,

harmonically most forward-looking

of them all,

Wagner, whose

death, before he

could conduct a promised

cycle of the symphonies,

left Bruckner heartbroken.

John

Warrack

|

|

|