|

|

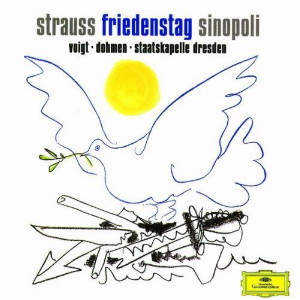

DG - 1

CD - 463 494-2 - (p) 2001

|

|

| Richard STRAUSS

(1864-1949) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Friedenstag |

|

75' 58" |

|

| Opera

in one act (Libretto: Joseph Gregor) |

|

|

|

| - 1.

"Hast was gesehn?" (Wachtmeister,

Schütze) |

3' 14" |

|

|

| - 2.

"La rosa, ch'è un bel fiore" (Piemonteser,

Konstabel, Schütze, Musketier, Hornist,

Soldaten) |

5' 23" |

|

|

| - 3.

"Hunger!" ... "Ich höre was" (Volksmenge,

Schütze, Konstabel, Wachtmeister,

Hornist, Musktier, Soldaten, Offizier) |

3' 17" |

|

|

| - 4.

"Hunger - Brot!" ... "Hier ist des Kaisers

Boden" (Volksmenge, Kommandant,

Bürgermeister, Deputation, Prälat,

Soldaten) |

5' 15" |

|

|

| - 5.

"Mein Kommandant!" ... "Rede!" (Frontoffizier,

Kommandant, Volksmenge, Deputation,

Frau) |

2' 48"

|

|

|

| - 6.

"Es sei! Doch hört" (Kommandant,

Deputation, Volksmenge, Soldaten) |

4' 35" |

|

|

| - 7.

"Zu Magdeburg in der Reiterschlacht" (Kommandant,

Wachtmeister, Konstabel, Schütze,

Musketier, Hornist, Soldaten) |

4' 57" |

|

|

| - 8.

"Geht, geht alle!" (Kommandant) |

2' 02" |

|

|

| - 9.

"Wie? Niemand hier?" (Maria) |

8' 36" |

|

|

| - 10.

"Nein - Ieere Hoffnung alles!" (Maria,

Kommandant) |

2' 38" |

|

|

| - 11.

"In einer Stunde verschwindet diese Stadt"

(Kommandant, Maria) |

3' 36" |

|

|

| - 12.

"Der Kaiser stand im Saal" (Kommandant,

Maria) |

5' 33" |

|

|

| - 13.

"Erwünschtes Zeichen!... Auf eure Posten!"

(Kommandant, Wachtmeister, Soldaten) |

1' 16" |

|

|

| - 14.

"Nein, nicht Todesnebel" (Maria,

Wachtmeister, Konstabel, Schütze) |

2' 47" |

|

|

| - 15.

"Der Feind, der Feind! Wo steht sein

Angriff?" (Kommandant, Wachtmeister,

Schütze, Maria, Offizier) |

1' 22" |

|

|

| - 16.

"Das Zeichen, das Zeichen, das Ihr uns

verhießet" (Bürgermeister, Prälat,

Deputation, Soldaten, Kommandant) |

4' 09" |

|

|

| - 17.

"Wo ist der Mann, des Krieges bester

Held?" (Holsteiner, Kommandant,

Volksmenge, Maria) |

3' 52" |

|

|

| - 18.

"Geliebter, nicht das Schwert!" (Maria,

Volksmenge, Deputation, Soldaten,

Bürgermeister, Prälat) |

5' 21" |

|

|

| - 19.

"Warum kämpften wir Jahre um Jahre?" (Kommandant,

Holsteiner, Maria, Volksmenge) |

2' 50" |

|

|

| - 20.

"Wagt es zu denken" (Alle) |

2' 29" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Albert DOHMEN, Kommandant

der belagerten Stadt |

STAATSOPERNCHOR

DRESDEN |

|

| Deborah VOIGT, Maria,

seine Frau |

Matthias Brauer, Chorus

master |

|

| Alfred REITER, Wachtmeister |

STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Tom MARTINSEN, Schütze |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

| Jochen KUPFER, Konstabel |

|

|

| André ECKERT, Musketier |

|

|

| Jürgen COMMICHAU,

Hornist |

|

|

| Jochen

SCHMECKENBECHER, Offizier |

|

|

| Matthias HENNEBERG,

Frontoffizier |

|

|

| Johan BOTHA, Ein

Piemonteser |

|

|

| Attila JUN, Der Hosteiner

/ Kommandant der Belagerungsarmee |

|

| Jon VILLARS, Bürgermeister |

|

|

| Sami LUTTINEN, Prälat |

|

|

| Sabine BROHM, Frau

aus der Deputation |

|

|

Die Deputation

|

|

|

Norbert Klesse, Ekkehard Pansa,

Rafael Harnisch

|

|

Soldaten, Volksmenge

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lukaskirche,

Dresden (Germania) - settembre

1999 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer

|

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording

Producers |

|

Arend

Prohmann, Klaus Hiemann |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Jürgen

Bulgrin, Wolf-Dieter Karwatky |

|

|

Editing |

|

Oliver

Curdt |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 463 494-2 | LC 0173

| 1 CD - 75' 58" | (p) 2001 |

DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FRIEDENSTAG -

a noble, humanitarian idea

Friedenstag

is at once the last real

product of Strauss’s

collaboration with Stefan

Zweig and his first opera

written to a libretto by

Joseph Gregor, Zweig’s

designated successor. One of

the composer’s least performed

works, it remains

controversial both for its

genesis and for its message.

Although that message - or at

least what can be termed Friedenstag's

ideological stance - was

largely of Zweig’s devising,

the composer never seriously

contested it, however much he

may have fretted over the

opera’s lack of theatrical

qualities. His greatest

challenge lay in expressing

the message clearly in the

Third Reich, where propaganda

could take a work intended to

express the highest

humanitarian and liberal

ideals and proclaim it "the

first Nazi opera". Its failure

to sustain such a preposterous

claim is confirmed by Friedenstag's

tenuous hold on the German

repertory after 1938. Whether

Strauss truly created an

effective vehicle for Zweig’s

lofty ideas, however, is also

debatable, and the question

has only partly to do with his

music.

Friedenstag

was conceived during the

crisis in Strauss’s

relationship with the Third

Reich engendered by his

collaboration with Zweig, who

was Jewish, in the comic opera

Die schweigsame Frau.

This episode led Zweig to

sever all ties with Germany,

even to the point of

abandoning further proposed

collaborations with Strauss.

He did, however, remain

sufficiently friendly towards

the composer to keep some of

their intended projects alive,

albeit now with his close

friend, the writer and theatre

historian Joseph Gregor, as

librettist. Although the

operas that Strauss created

with Gregor comprise a

distinct chapter in his

career, Zweig’s shadow falls

over Friedenstag to

such an extent that Kenneth

Birkin has called it “the only

one of these operas which took

its form and dramatic

substance exclusively from

him".

The work originated in a

seemingly chance remark by the

composer in a letter of 2

February 1934, as he attempted

to renew the collaboration

with Zweig in the interval

between the completion and

première of Die

schweigsame Frau.

Strauss’s suggestion of “a

fine single-act festival

piece" on Henry III and the

“Peace of Constance" of 1043

arose from his reading of

Leopold Ziegler’s Das

heilige Reich der Deutschen.

The peace, or “Day of

Indulgence”, at which the

Salian Emperor Henry III

promised to forgive his

enemies and urged them to

behave similarly was one of

several such episodes in the

history of medieval kingship

and diplomacy and offered the

opportunity for a display of

usually temporary

rapprochement.

The idea

of reconciliation between

deadly opponents appealed to

the humanitarian and pacifist

side of Zweig, but at the back

of his mind were other

inspirations, notably

Velasquez’s Surrender of

Breda and Calderón’s

play on the same subject, Et

sitio de Bredá. A famous

episode in the Eighty Years

War between Spanish and Dutch,

the surrender of Breda to the

former in 1625, had been

marked by unaccustomed

clemency on the part of the

victors. In his first draft of

Friedenstag in late

1934, Zweig moved the

situation and the sentiments

forward to 1648 and the end of

the Thirty Years War,

sharpening the idea of

reconciliation by its new

associations with the

bloodiest conflict in German

history before the 20th

century. The subject became

the renunciation of hate

between rival commanders and

armies, between rival

religions (symbolizing

ideologies), between besiegers

and besieged. As a result, the

work was sometimes described

in its earliest stages as [24.

Oktober] 1648, "...the

last day of the Thirty Years

War in the citadel...", and Der

erste Friedenstag,

before the familiar title was

adopted in October 1935.

Nonetheless a civil war is a

two-edged symbol, almost as

much so as Henry III’s gesture

of Gleichschaltung. Friedenstag

could also be viewed as a

symbol for the “Burgfriede”

that descended on Germany

after the partisan strife of

the Weimar Republic, a

metaphor for the new Reich

that was just about

sustainable once Zweig was

replaced as librettist by

Gregor. Yet Zweig continued to

haunt the project to its

conclusion.

As early

as his first draft, Zweig

began backing out of the

collaboration, which also

embraced several other

projects, including the germ

of the idea that later grew

into Capriccio and an

opera based on Calderon’s Semiramis.

The first thing that Gregor

showed the composer was a

sketch for Semiramis,

which was criticized so

trenchantly by Strauss and (to

a lesser extent) Zweig that

the collaboration nearly

collapsed. That Gregor was for

long regarded as a mere

intermediary is evident from

Strauss’s insistence that

Zweig should vet subsequent

material. While the disaster

of Die schweigsame Frau

was moving to its climax in

Dresden, Strauss and Zweig met

in Austria to shape the new

collaboration with Gregor, who

visited Garmisch in order to

have several projects

considered. Strauss eventually

agreed to three, two of which

were Friedenstag and

the pastoral tragedy Daphne.

Here was the origin of an

association between these two

works that was particularly

important to Gregor and led to

their later joint première in

Dresden on 15 October 1938.

That the collaboration was to

begin with the one-act Friedenstag

seemed particularly

appropriate to Zweig on

practical grounds, suggesting

that he shared some of

Strauss’s misgivings about

Gregor’s tendency in his

verses towards the antiquated

and high-flown.

What

Gregor could not be charged

with was laziness. Having met

Strauss on 7 July, within a

fortnight he had a new draft

ready that included at least

one happy invention, the

episode of the Piedmontese

messenger that gave the

composer the chance of writing

Italianate pastiche as an

antidote to the harsh

sound-world already planned

forthe opera. Strauss

continued to criticize

Gregor’s poetic style

relentlessly, and the libretto

went through several versions

before the poet turned in

despair to Zweig in November

1935 to create the scene of

reconciliation between the

commanders of the rival

armies, the heart of the

original vision. By this time,

however, Strauss had a firm

grasp on the shape of the

opera, which he had never

really seen as anything other

than that “fine single-act

festival piece” of his first

letter. Zweig’s verses of

reconciliation were discarded

in favour of a version that

focussed firmly on the final

chorus of rejoicing,

reinforcing the curious

facelessness of a drama in

which only one character is

named. When the score was

finished in draft in January

1936, the noble and

humanitarian idea had been

carried through to an ending

that seems oddly lacking in

true energy and passion.

Partly this lay in the cloak

of anonymity that lay over the

besieged town, commanders and

soldiers, a decision that

emphasized the universality of

Zweig’s message and which he

refused to water down by

introducing a love episode in

order to appease Strauss’s

instinct for the operatic

stage. Partly it was due to

the libretto, about which

Zweig expressed mild doubts to

Gregor, but Friedenstag's

failure to achieve true

success has at least something

to do with Strauss’s music.

The

subject took Strauss out of

his increasingly domestic

musical milieu into areas that

had proved taxing for him in

the past. Over the first part

of the opera hung a pall of

martial gloom that emanated

from the dour intransigence of

the Catholic commander.The

world of chivalry had not been

a notable success for him,

however, unless diluted with

comedy and irony as in Don

Quixote. From the grim

tritones of the opening, the

composer is working in a novel

martial and austere vein that

is lightened only slightly by

the Italianate pastiche of the

Piedmontese messenger. By no

means unsuccessful on its own

terms, the brass-bound music

of the commander presents

Strauss’s characteristic

chromatic language tied to a

more rigid rhythmical scheme

which is appropriate to the

subject but deprives Strauss’s

musical style of some of its

more familiar features.

The final

chorus of reconciliation took

Strauss into territory that he

had visited before in episodes

of his tone poems and in parts

of Die Frau ohne Schatten.

In that opera, the prolonged

glorification at the

conclusion worked by the skin

of its teeth, as Strauss’s

mastery of tension and climax

compensated for flagging

melodic inspiration. The

problem similarly affects the

insistently affirmative C

major close of Friedenstag,

in which Strauss comes

perilously close to the empty

heroics of his festival music

and occasional pieces. That

left the salvaging of the

opera firmly in the hands of

Maria, the Catholic

commander’s wife, whom Strauss

insisted on naming (unlike the

Woman in Die Frau ohne

Schatten, who was

humanized by contact with

Barak). In accordance with

Zweig’s ideas, her dialogue

with the commander eschewed

conventional eroticism and

became a clash of martial

honour and duty with the

self-sacrificing spirit ot

Beethoven’s Leonore. While

declaring her love for her

husband, Maria provides a

biting critique of war.

Somewhat surprisingly, in view

of the lyrical style Strauss

normally reserved for his

later heroines, he managed to

blend Maria’s tendency to

cantilena with the block

chords and fanfares of the

commander, anticipating the

manner in which he built

Apollo’s heroic music into the

lyrical pastoral of Daphne.

In keeping with the dramatic

nature of Strauss’s genius,

this worked best in evoking

ideological conflict, less

well in the moment of

reconciliation, where the role

of the bells does not sustain

the importance Zweig attached

to them as the first harbinger

ol peace; significantly it was

here that Gregor complained to

Zweig that the process of

creation had "ground to a

halt".

When the

opera was finished, Gregor

praised the ending’s

similarity to the close of

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (a

comparison that amused the

composer) and to Also

sprach Zarathustra:

“simple, monumental, truly

pure dome-like C major, not

even broken up by the B, as in

Zarathustra”. In spite

of the novelty of many

passages in Friedenstag,

and of the fine music for the

central dramatic clash, it is

legitimate to wish for some of

that B, which may also have

occurred to composer and

librettist when they planned

to make Friedenstag a

finale to Daphne. In

the end this double première

was anticipated by an earlier

performance of Friedenstag

on 24 July 1938 in Munich

featuring the dedicatees

Clemens Krauss and Viorica

Ursuleac as conductor and

Maria, and with Beethoven’s Prometheus

ballet music in the first

half. Thus the opera came to

be associated with no less

than three works by Beethoven:

Fidelio, the Ninth

Symphony and Prometheus.

By the cruellest of ironies,

Zweig’s great project of

reconciliation was plundered

then ignored by the Nazi

regime while Strauss played at

being Beethoven. The message

of Friedenstag was

already clouded by political

and musical myths as Gregor

steered its composer back to

Greek mythology and idealized

pastoral.

John

Williamson

|

|

|