|

|

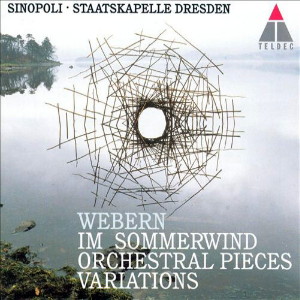

Teldec

- 1 CD - 3984-22902-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| Anton WEBERN

(1883-1945) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Im

Sommerwind (Idyll for

Large Orchestra after a poem by Bruno

Wille) |

|

12' 44" |

|

| -

Ruhig bewegt |

12' 44" |

|

|

Passacaglia,

Op. 1

|

|

10' 51" |

|

| -

Sehr mäßig, Tempo I |

10' 51" |

|

|

| Six

Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6 (arr. for

reduced orchestra 1928) |

|

13' 08" |

|

| -

1. Etwas bewegt |

0' 55" |

|

|

| -

2. Bewegt |

1' 22" |

|

|

| -

3. Zart bewegt |

1' 04" |

|

|

| -

4. Langsam marcia funebre |

4' 56" |

|

|

| -

5. Sehr langsam |

2' 53" |

|

|

| -

6. Zart bewegt |

1' 52" |

|

|

| Five Orchestral

Pieces, Op. 10 |

|

4'

50"

|

|

| -

1. Sehr ruhig und zart |

0' 57" |

|

|

| -

2. Lebhaft und zart bewegt |

0' 37" |

|

|

| -

3. Sehr langsam und äußerst ruhig |

1' 47" |

|

|

| -

4. Fließend, äußerst zart |

0' 38" |

|

|

| -

5. Sehr fließend |

0' 51" |

|

|

| Symphony, Op. 21 |

|

8' 55" |

|

| -

1. Ruhig schreitend |

6' 03" |

|

|

| -

2. Variationen - Thema: Sehr ruhig ·

Variations 1-7 |

2' 52" |

|

|

| Concerto, Op. 24 (for

flute, oboe, clarinet,

horn, trumpet, trombone,

violin, viola and piano) |

|

5' 54" |

|

| -

1. Etwas lebhaft |

2' 33" |

|

|

| -

2. Sehr langsam |

2' 06" |

|

|

| -

3. Sehr rasch |

1' 15" |

|

|

Variations, Op.

30

|

|

7' 01" |

|

| -

Lebhaft |

7' 01" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lukaskirche,

Dresden (Germania) -

settembre/ottobre 1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

producer |

|

Renate

Kupfer |

|

|

Recording

producers |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Christian

Feldgen |

|

|

Assistant

engineers |

|

Peter

Weinsheimer, Tobias Lehmann

|

|

|

Digital editing |

|

Andreas

Florcyak |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Teldec |

3984-22902-2 | LC 6019 | 1

CD - 64' 13" | (p) 1999 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anton

Webern and Viennese

Espressivo

Webern's music is a

continuation of the

19th-century musical tradition

inasmuch as it is imbued with

a radical desire to be

expressive, something which

the Viennese Classical period

and late Romantic composers

such as Richard Strauss,

Gustav Mahler, and Arnold

Schoenberg had sought in an

ideal of compositional style

and performance best summed up

by the term "Viennese

espressivo". A modern in-depth

analysis of the past no longer

perceives Webern to be a

central figure of the 20th

century. Rather, he is now

seen as the composer who took

the tradition of the "Viennese

Classical period" as far as it

could go. This is reflected

not only in his music’s

obvious striving for

expressivity but also in its

use of the “fragmentation

technique” principle, whereby

a thematic line is distributed

among several instruments.

Thus the most pressing problem

that has to be solved by

performers of Webern’s works

is the question of how to

render and indeed make audible

melodic lines which are

considerably extended and

often interrupted by rests. In

contrast to serial music, the

individual notes should not be

heard as pointillist dots.

Rather, they should use their

impulsive energy to reach

beyond themselves, to touch

the next note played by

another instrument, and then

to blend into it.

Anton

Webern left a precisely

defined total of exactly 31

works, the first and last of

which are linked by the

principle of developing

variation. He deliberately

assigned his first opus number

to the Passacaglia op.

l, which he wrote in 1908, for

this was the gateway which was

to lead to the rest of his

life’s work. It was a

demonstrative sign that he had

attained independence, for he

only began to number his works

after he had officially

completed his composition

studies with his teacher,

Arnold Schoenberg.

The

symphonic poem IM SOMMERWIND

of 1904, which was based on

the poem of the same name in

Bruno Wille's novel Offenbarungebn

des Wacholderbaums

(Revelations of the Juniper

Tree), has the subtitle,

“Idyll for Large Orchestra”.

It still bears traces of

Webern’s interest in the genre

of the symphonic poem, and the

poetic symphonic style which

he had encountered in the

music of Richard Strauss,

Arnold Schoenberg, and Gustav

Mahler. It is easy to

understand why the composer

did not subsequently include

this piece in his list of

works. Yet it already

possesses certain features

which were destined to become

characteristic of his later

pieces, for example, the

importance of tone colour as

an aspect of composition, as

something which does not

merely illustrate the musical

events, but is capable of

generating expressivity of its

own accord. For this reason

the piece is far more modern

than Strauss. It has links

with the orchestration of

Webern’s later works and the

vibrant textures of Claude

Debussy.

The PASSACAGLIA OP. 1 (1908)

contains as if in a nutshell

all the motivic shapes which

were to follow it. It is based

on the familiar kind of

thematic passacaglia bass

found in Beethoven’s Eroica

Variations op. 35 and

the finale of Brahms’s Fourth

Symphony. However, a kind of

invention peculiar to Webern

becomes apparent in the rests

inserted in the attenuated

passacaglia theme. The muted

pizzicato of the strings

produces sounds which are

meant to be connected, despite

the intervening rests. At the

same time, the rests,

construed in terms of what the

19th century called “eloquent

rests”, are as important and

meaningful as the notes

themselves. This foreshadows

one of Webern's central

preoccupations, which was to

base a composition on

attenuation, empty spaces, and

silence. The fact that

deliberate emptiness is more

powerful than loud activity is

seen again and again,

especially in the free

sections of the ensuing cycle

of 23 variations, which are

full of dramatic commotion and

massed chords.

However, op. 1 was still a

continuously linear structure,

which, despite its numerous

episodes, strove towards a

symphonic climax in a rather

dramatic manner. On the other

hand, at first sight the SIX

ORCHESTRAL PIECES OP. 6

[Revised version, 1928] seem

to be character pieces which

combine long chunks taken out

of larger contexts. And the

FIVE ORCHESTRAL PIECES OP. 10

(1911-13) seem to be

compressed even more, and are

tantamount to a greatly

abbreviated version of the op.

6 Orchestral Pieces. That is

the reason why, together with

the Bagatellen for

String Quartet op. 9, they

have been described as

aphorisms - rightly so,

perhaps, in view of the fact

that they are abbreviations of

formerly extended forms. There

are funeral marches and

imaginary nocturnes which are

reminiscent of Mahler’s Fifth

and Seventh Symphonies. But,

when

compared with the very brief

and extremely compressed

pieces, they are either so

long that, like the concluding

pieces of opp. 6 and 10, they

seem to be never-ending, or

they are so short that the

listener, if he is to follow

them at all, believes he has

to look at them with a

telescope in order to magnify

them sufficiently to make them

consciously comprehensible and

audible.

During his lengthy middle

period, between the op. 11

cello pieces (1914) and the

op. 20 String Trio (1926-27),

Webern wrote only vocal

pieces, working towards a new

style by grappling with the

metaphorical use of colour in

the poetry of Georg Trakl. ln

this connection, his path to

"composition with twelve notes

related solely to each other"

is not as important as the new

manner of writing as it were

weightless vocal and

instrumental parts which are

all finely balanced. In the

orchestral works after op. 21

this leads to a situation

where the voices are all

equal. Since each one is

equally close to the thematic

process of the basic motivic

shapes, none of them can be

understood in figurative or

ornamental terms.

Although the SYMPHONY OP. 21

(1927-28) with its two

movements is reminiscent of

more traditional two-movement

and cyclical works of the

symphonic and instrumental

repertoire (such as

Beethoven’s opp. 90 and 111

Piano Sonatas, and Schubert’s

“Unfinished” Symphony), Webern

is nonetheless pursuing a

different path, and initially

this is to “return” to the

kind of binary sonata form on

which the first movement of

the symphony is based.

Construing sonata form as

ternary began with theorists

who took their bearings from

Beethoven’s symphonies.

However, around 1780, the

“development section and

recapitulation” continued to

be thought of as a single

second section which followed

on the first, the

“exposition”, Webern

emphasized his historical

model by repeating both the

first and second sections,

thereby underlining the

reference to binary sonata

form.

The second movement is based

on another architectural and

formal principle which is

quite different to the linear

and dynamic formal processes

of Beethoven’s symphonies. The

twelve-note row is arranged

symmetrically around the

centre of a tritone, and makes

use of mirror techniques,

which can also be heard when

the basic shapes are linked

(for example, in the first

variation, bar 17 onwards, the

retrograde in violin 1).

Webern also transfers these

structural thematic

relationships to the formal

architecture. The theme with

seven variations and a coda

becomes denser and denser on

the basis of a symmetry which

proceeds from without to

within up to the “middle” of

the fourth variation. Thus the

framing variations I:VII -

II:VI - III:V correspond to

each other in a variety of

ways, whereas the fourth is

the ambivalent centre between

the theme of the variations

and the coda. Thus we are

dealing with a cross between

the classical and organic

formal schema of the late-18th

century and the architectural

and symmetrical schema of the

kind employed by ]. S. Bach in

the Goldberg Variations

and in the Actus tragicus

cantata.

Bach’s kind of formal

architecture is also of

importance in the CONCERTO FOR

NINE INSTRUMENTS OP. 24

(1931-34), Thus, on 19

September 1928, whilst engaged

in making the first draft,

Webern wrote to his publisher

Emil Hertzka: “In the meantime

I have already turned my

attention to a new work, a

Concerto for violin, clarinet,

horn, piano and string

orchestra. (In the style of

some of Bach’s Brandenburg

Concertos.)”

The influence of J. S. Bach,

over and above the reference

to him in the letter, was of

very great importance. In

fact, when Webern was notating

the final version of op. 24 in

1934, he was engaged in

orchestrating the six-part

Ricercar from Bach’s Musical

Offering.

Webern's penultimate work, the

VARIATIONS FOR ORCHESTRA OP.

30 (1940), completes the

circle leading back to op. 1.

The idea of developing a

formal process out of an

unbelievably complex and

multidimensional thematic

shape which on various levels

externalizes what was implicit

in the basic shape is of

fundamental importance for the

whole of Webern’s work. For

this reason, Webern’s themes,

especially in his sets of

variations, are not points of

departure, but goals and

conclusions from which the

composition is developed back

to its beginning. (It is no

accident, therefore, that many

of his forms are retrograde,

or present the basic shape of

the row in the second

movement, and not at the

beginning.) In a letter to the

Swiss critic and musicologist

Willi Reich written on 3 May

1941 Webern explained:

"Everything which occurs in

the piece (op. 30) is based on

the two ideas, which are

presented in the first and

second bars (double bass and

oboe)! But it is reduced even

further, for the second shape

(oboe) is already in itself

retrograde: the second two

notes are the retrograde of

the first two, though

rhythmically augmented. It is

again followed, in the

trombone, by the first shape

(double bass), but in

diminution! And in retrograde

with regard to motifs and

intervals. For that is how my

row is constructed, which is

made up of these thrice four

notes."

Martin

Zenck

(Translation:

Alfred Clayton)

|

|

|