|

|

DG - 1

CD - 457 587-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

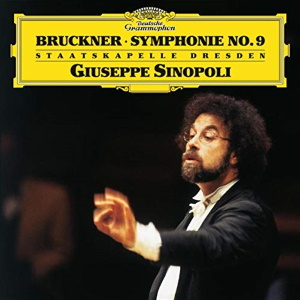

| Anton BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie Nr. 9

d-moll |

|

62' 13" |

|

| Edition:

Leopold Nowak |

|

|

|

| -

1. Feierlich, Misterioso |

25' 42" |

|

|

| -

2. Scherzo.

Bewegt, lebhaft - Trio. Schnell |

10' 15" |

|

|

| -

3. Adagio.

Langsam, feierlich |

26' 16" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Semperoper,

Dresden (Germania) - marzo 1997 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Werner

Mayer |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineers

|

|

Rainer

Hoepfber, Wolfgang Werner |

|

|

Editing |

|

Ingmar

Haas

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 457 587-2 | LC 0173 |1

CD - 62' 13" | (p) 1999 | 4D DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The son of an

Upper Austrian village

schoolmaster, Bruckner lived

simply as a teacher and

organist; only in his early

30s

did he seriously begin

composition. A humble,

modest and eccentric

personality, his life and,

as a consequence, his music,

was dedicated to the glory

of God. It

took until the 1880s before

his work began to receive

the recognition and success

it deserved. True he had his

disciples and admirers,

among them the composer Hugo

Wolf and the conductors

Ferdinand Löwe.

Franz Schalk and later Artur

Nikisch and Hans Flichter.

But in general his was a

life battered and bruised by

critical reception, mostly

at the expense of the

enormously influential

Viennese critic Eduard

Hanslick. Bruckner fervently

admired Wagner and dedicated

his Third Symphony to the

German composer, but by

allying himself to the Master

of Bayreuth he alienated

himself from much of the

Viennese public who

preferred Brahms, who lived

in their midst. Much

had been made of this

schism, but in reality

Brahms, Wagner and Bruckner

held each other in mutual

regard despite their widely

differing personalities. It

was mischief-making among

their supporters which did

the damage.

Bruckner was a

perfectionist and extremely

sensitive to comment and

criticism. Following the

success of the Seventh

Symphony under Nikisch at

Leipzig in December 1884 (a

triumph which began to

spread the composer`s name

far and wide) he began to

discover in himself a

self-confidence which had

been sadly lacking before.

He began to sketch out his

Ninth Symphony in 1887 just

a couple of days before

completing the final touches

to his massive Eighth, which

he sent off to the conductor

Hermann Levi. This proved

his undoing, for Levi

confessed himself totally

bewildered by the work and

declined to conduct it,

Bruckner was shattered and

immediately set to work

revising and rescoring not

only the Eighth but also

making further revisions to

his first three symphonies.

The result was that the

Ninth was consigned to the

back burner, and eventually

it took the nine remaining

years of Bruckner’s life to

complete the three extant

movements we have today.

Perhaps if Richter (who in

the end conducted the

premiere of the Eighth in

1892) had been the recipient

rather than Levi,

we would have a finale for

the Ninth. As death

approached, in the autumn of

1896, Bruckner’s friends

realized that it was not to

be forthcoming. Richter even

suggested to him that his Te

Deum might make a fitting

conclusion in the way that Beethoven’s

Ninth had a triumphant

choral ending, and,

according to the conductor,

Bruckner was not averse to

the idea. It was followed at

the first performance in

February 1903, under Löwe,

but the result was far

from satisfactory. It

took until 1932 before the

authentic version of the

symphony was heard. Mercifully

the 200 or so pages of

sketches for the fourth

movement that remain do not

provide the basis for

someone to complete what is

already in itself a fitting

conclusion to Bruckner’s

life. His

earlier symphonies often

resolve the anguish of his

complex personality in their

first three movements by a

triumphant finale in which

the Greater Glory of God

seems to have a hand. It is

fitting that the Ninth,

without any such resolution,

stands alone as a stark

statement of the mans

character.

Beethoven's influence is

evident from the outset,

building from a hushed

tremolo of strings (also

found in Bruckner’s First

and Fourth Symphonies) to a

massive unison outburst of

the full orchestra. It

develops into one of the

most original of movements,

with the borders of

conventional sonata form

(exposition, development and

recapitulation) far less

discernible than his

previous symphonies. The

essential and familiar

Brucknerian ingredients,

those terraced blocks of

sound, the organist’s feel

for registration and tonal

colour, are all there, so

too is the contrast between

noble themes and stark,

angular motifs. The scherzo

comes next (as it does in

only his String Quintet and

the Eighth Symphony), and

though it may appear to be a

danse macabre with an

even faster trio section, it

also provides a necessary

contrast to the tensions of

the first movement. With

the concluding Adagio,

described by many as

Bruckner’s farewell to life

and reportedly by himself as

"the

finest I have ever written,

it impresses me whenever I

play it", Bruckner uses two

alternating themes, the

first comprised of

wide-arching intervals, the

second an expansive melody

given to the violins. After

a climax of agonized

dissonance (no visionary

grand apotheosis here as in

the Adagios of the preceding

Seventh and Eighth

Symphonies) there descends

an uneasy peace, one which

might have been resolved in

that elusive missing finale.

Christopher

Fifield

|

|

|