|

|

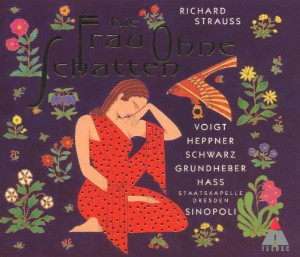

Teldec

- 3 CDs - 0630-13156-2 - (p) 1997

|

|

| Richard

STRAUSS (1864-1949) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Die Frau Ohne

Schatten |

|

184' 21" |

|

| Oper in drei

Akten (Libretto: Hugo von

Hofmannsthal) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

67'

55" |

|

| ERSTER

AUFZUG |

1.

"Licht überm See" - Amme,

Geisterbote |

5' 42" |

|

|

|

2.

"Amme! Wachst Du?" - Kaiser,

Amme |

5' 34"

|

|

|

|

3. "Ist mein

Liebster dagin" - Kaiserin,

Amme |

3' 52" |

|

|

|

4.

"Wie soll ich denn nicht weinen?" -

Stimme des Falken, Kaiserin, Amme |

2' 19"

|

|

|

|

5.

"Amme, um alles, wo find ich den

Schatten?" - Kaiserin, Amme |

5' 10" |

|

|

|

6.

Verwandlung: Erdenflug |

1' 40"

|

|

|

|

7.

"Dieb! Da nimm!" - Einäugiger,

Einarmiger, Buckliger, Frau, Barak |

2' 30" |

|

|

|

8.

"Sie aus dem Hause" - Frau,

Barak |

8' 14" |

|

|

|

9.

"Dritthalb Jahr bin ich dein Weib" -

Frau, Barak |

5' 35" |

|

|

|

10.

"Was vollt ihr hier?" - Frau,

Amme, Kaiserin |

6' 42" |

|

|

|

11.

"Ach Herrin, süße Herrin!" - Dienerinnen,

Kaiserin, Jüngling, Frau |

3' 37" |

|

|

|

12.

"Hat es dich blutige Tränen

gekostet" - Amme, Frau |

6' 04" |

|

|

|

13.

"Mutter, Mutter, laß uns nach

Hause!" - Kinderstimmen, Frau |

2' 33" |

|

|

|

14.

"Trag' ich die Ware selber zu Markt"

- Barak, Frau |

3' 01" |

|

|

|

15.

"Ihr Gatten in den Häisern dieser

Stadt" - Stimmen der Wächter,

Barak |

5' 22" |

|

|

|

16.

"Du bist verflucht" |

5' 08" |

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

57'

02" |

|

| ZWEITER

AUFZUG |

1.

"Komm bald wieder nach Haus, mein

Gebieter" - Amme, Frau,

Kaiserin, Frauenchor |

4' 16" |

|

|

|

2.

"Was ist nun deine Rede, du

Prinzessin" - Barak, Brüder,

Bettelkinder, Frau |

4' 08" |

|

|

|

3.

Verwandlung |

0' 52" |

|

|

|

4.

"Falke, Falke, du wiedergefundener"

- Kaiser |

13' 38" |

|

|

|

5.

"Es gibt derer, die haben immer

Zeit" - Frau, Barak, Amme |

3' 26" |

|

|

|

6.

"Schlange, was hab' ich mit dir zu

schaffen!" - Frau, Jüngling,

Amme, Barak |

3' 12" |

|

|

|

7.

"Ein Handwerk verstehst du sicher

nicht" - Frau, Barak |

5' 42" |

|

|

|

8.

"Ich, mein Gebieter" · Verwandlung -

Kaiserin |

5' 16" |

|

|

|

9.

"Zum Lebenswasser!" - Männerchor,

Stimme des Falken |

2' 08" |

|

|

|

10.

"Wehe, mein Mann!" - Kaiserin |

3' 49" |

|

|

|

11.

"Es dunkelt, daß ich nicht sehe zur

Arbeit" - Barak, Brüder, Amme,

Kaiserin, Frau |

1' 49" |

|

|

|

12.

"Es gibt derer, die bleiben immer

gelassen" - Frau, Barak |

3' 27" |

|

|

|

13.

"Sie wirft keinen Schatten" - Brüder,

Amme, Barak, Kaiserin |

1' 52" |

|

|

|

14.

"Barak! Ich hab' es nicht getan!" -

Frau, Brüder, Amme |

3' 27" |

|

|

|

Compact Disc 3 |

|

59'

24" |

|

| DRITTER

AUFZUG |

1.

"Schweigt doch, ihr Stimmen!" - Frau |

8' 05" |

|

|

|

2.

"Mir anvertraut" - Barak, Frau |

3' 43" |

|

|

|

3.

"Auf, geh nach oben, Mann" - Stimme

von oben, Frau, Dienende Geister,

Geisterbote |

5' 02" |

|

|

|

4.

"Fort von hier" - Amme, Kaiserin |

6' 20" |

|

|

|

5.

"Aus unsern Taten steigt ein

Gericht!" - Kaiserin |

3' 18" |

|

|

|

6.

"Wehe, mein Kind" - Amme,

Sopranstimmen, Geisterbote, Stimme

der Frau, Stimme Baraks |

2' 07" |

|

|

|

7.

Verwandlung - Kaiserin, dienende

Geister, Frai, Barak |

2' 23" |

|

|

|

8.

"Vater, bist du's?" - Kaiserin,

Hüter der Schwelle, Stimme der

Frau, Stimme Baraks |

8' 47" |

|

|

|

9.

"Mein Liebster starr!" - Kaiserin,

Unirdische Stimmen, Hüter der

Schwelle, Stimme der Frau, Stimme

Baraks |

3' 33" |

|

|

|

10.

"Wenn das Herz aus Kristall" - Kaiser,

Stimmen der Ungeborenen, Kaiserin |

5' 12" |

|

|

|

11.

Verwandlung |

1' 33" |

|

|

|

12.

"Trifft mich sein Lieben nicht" - Frau,

Barak, Stimmen der Ungeborenen |

2' 29" |

|

|

|

13.

"Nun will ich jubeln" - Barak,

Kaiser, Stimmen der Ungeborenen,

Kaiserin, Frau |

4' 39" |

|

|

|

14.

"Vater, dir drohet nichts" - Stimmen

der Ungeborenen |

2' 13" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Horst HIESTERMANN,

HERODES, Tetrarch von Judäa |

CHOR DER SÄCHSISCHEN

STAATSOPER DRESDEN |

|

| Leonie RYSANEK,

HERODIAS, Gemahlin des Tetrarchen |

Matthias Brauer, Chorus

master |

|

| Deborah VOIGT, Die

Kaiserin |

STAATSKAPELLE

DRESDEN |

|

| Ben HEPPNER, Der

Kaiser |

Roland Starumer, Solo

violin |

|

| Hanna SCHWARZ, Die

Amme |

Jan Vogler, Solo

violoncello |

|

| Hans-Joachim

KETELSEN, Der Geisterbote |

Sascha Reckert, Glass

harmonica |

|

| Ute SELBIG, Ein

Hüter der Schwelle des Tempels |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

| Werner GÜRA, Die

Erscheinung eines Jünglings |

Musical assistance:

David Miller |

|

| Sabine BROHM, Die

Stimme des Falken |

|

|

| Nadja MICHAEL, Eine

Stimme von oben |

|

|

| Franz GRUNDHEBER,

Barak, der Färber |

|

|

| Sabine HASS, Sein

Weib |

|

|

| Des Färbers Brüder |

|

|

| Andreas Scheibner,

Der Einäugige |

|

|

| André Eckert, Der

Einarmige |

|

|

| Roland Wagenfèhrer,

Der Bucklige |

|

|

| Die Stimmen der

Ungeborenen |

|

|

| Roxana Incontrera, Claudia

Kuny, Helga Termer,

Elisabeth Wilke, Nadja Michael |

|

| Die Stimmen der

Wächter der Stadt |

|

|

| Hans-Joachim Ketelsen,

Matthias Henneberg, Andreas

Scheibner |

|

| Die Dienerinnen |

|

|

| Christiane Hossfeld,

Barbara Hoene, Angela Liebold |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Semperoper,

Sächsische

Staatsoper,

Dresden (Germania)

- novembre/dicembre 1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

Based

on live performances

|

|

|

Executive

producer |

|

Renate

Kupfer |

|

|

Recording

producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Balance

engineer |

|

Michael

Brammann |

|

|

Assistant

engineers |

|

Tobias

Lehmann, Peter Weinsheimer, Jens

Schünemann/Niels Müller |

|

|

Digital editing |

|

Jens

Schünemann, Stefan Witzel |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Teldec |

0630-13156-2 | LC 6019 | 3 CDs -

67' 55", 57' 02" & 59' 24" |

(p) 1997 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Die Frau ohne

Schatten

Or, A Fairy-Tale by Two

Intellectuals

The

journey taken by Strauss and

Hofmannsthal from their first

joint reflections on the

subject in 1911 to the

completion of the whole opera

some six years later was long,

tortuous and not a little

fraught with difficulties. Die

Frau ohne Schatten -

this phantasmagorically

complex parable about the way

in which love is blessed with

the birth of children - was

itself the product of a

painful birth. The Great War

was still in progress when

Strauss completed the score in

1917 and so he decided to

delay the first performance

until the guns had fallen

silent and peace was restored

to the world. it proved a

lengthy wait, with the opera

finally being staged in Vienna

on 10 October 1919. The fact

that Strauss had considerable

difficulties with his literary

libretto and that

Hofmannsthal, too, had

problems with the often

obstinate and pernickety

composer, who appealed to

musical logic in support of

his arguments, was very much

in the nature of the material,

so dense is its literary

content. The voluminous

correspondence that passed

between the two collaborators

on the subject of the opera

(good-humouredly referred to

by Strauss by the shorthand

title of “Fr-o-Sch” [frog])

throws revealing light on the

special character of the

piece, on its obscure and

sometimes barely penetrable

passages, on its rampant

textual and musical symbolism

and on the effort involved in

ensuring that libretto and

musical imagery intermeshed as

closely as possible.

Also reflected here

are the difficulties that

mount up for any composer

faced by a text that is like a

finely woven fabric, the dense

textures of which are less

pervious to music than, say

the librettos of the great

italian operas with their

generally simple parole

scenicbe. Hofmannsthal

provided a libretto of immense

linguistic refinement, drawing

upon so many disparate epic

and dramatic sources that the

result is a text that teems

with manifold allusions to

other works, for all that the

librettist handles those

allusions in a highly discreet

and subtly veiled manner On

the one hand, therefore, we

have a libretto with ambitions

to fashionable and cultured

allusion, on the other a

composer whose task would have

been much simpler if the

libretto were to have

contained as many “open”

passages as possible, leaving

the composer to breathe life

into them with his music.

Understandable

Misunderstandings

Hofmannsthal had

something quite specific in

mind, he told Strauss in a

letter of 20 March 1911,

something

which

fascinates me very much and

which I shall certainly do,

either for music or as a

spectacle with accompanying

music [...]. It is a magic

fairy tale with two men

confronting two women [...].

The whole idea as I see it

suspended before my eyes

[...] would, incidentally

stand in the same relation

to Die Zauberflöte

as Rosenkavalier

does to Figaro.

Strauss’s reply was

as matter-of-fact as it was

pragmatic:

I

want to inquire how Frau

ohne Schatten is

doing: can’t I get a

finished draft or maybe even

a first act to look at some

time soon? (15 May 1911)

That Hofrnannsthal

had great difficulty imposing

any sense of coherent order on

such refractory material

became clear, not least, when

the intendants of the Court

Operas in Dresden and Berlin,

Count Nikolaus von Seebach and

Count Georg von Hülsen,

announced that they could make

neither head nor tail of the

scenario for the first two

acts, which had been sent to

them for their perusal. But

such difficulties still lay

ahead when Hofmannsthal wrote

to Strauss on 15 May:

The fact is that

with so fine a subject as Die

Frau ohne Schatten,

the rich gift of a happy

hour, with a subject so fit

to become the vehicle of

beautiful poetry and

beautiful music, with a

subject such as this all

haste and hurry and forcing

of oneself would be a crime.

[...] Had you made me choose

between producing this work

on the spot, or doing

without your music, I should

have chosen the latter.

Hofrnannsthals mood

veered cyclothymically between

euphoria and self-tormenting

brooding. On some occasions we

find him announcing that he

has finally been able to

organise all the scenes right

down to the very last detail,

but on other occasions he is

simply incapable of making a

start:

It is a terribly

delicate, immensely

difficult task and more than

once I have been in profound

despair. I have now

rewritten the first half of

Act I no less than three

times, from the first word

to the last, and even now I

have not got the final

version (5 June 1913).

Finally, on 28

December 1913, Hofrnannsthal

sent Strauss the opening act,

but his covering letter

continues to convey the

disquiet of a man still

groping to find his way:

Or

the five main characters in

the piece, the Emperor is

the least conspicuous [...].

What the music will have to

give him is not so much

pronounced characterization

as a more truly musical

element; he is to be the

sweet and well-tempered

voice throughout. Of the

threefold nature of the

Empress, part animal, part

human and part spirit, only

the animal and spirit

aspects are apparent in this

scene; these two together

make her the strange being

she is. [...] I have written

in the margin of the text

occasional notes about the

dual facets of the Nurse,

who vacillates between the

demoniac and the grotesque

(28 December 1913).

Strauss was pleased,

but found the length of the

acts problematical:

The

first act is simply

wonderful: so compact and

homogeneous that I cannot

yet think of even a comma

being deleted or altered (4

April 1914).

Hofmannsthal agreed,

while at the same time asking

Strauss not to forget that

the Empress is,

for the spiritual meaning of

the opera, the central

figure and her destiny the

pivot of the whole action.

The Dyer’s wife, the Dyer

are, admittedly the

strongest figures, but it is

not on them that the plot is

focused [...]. You should

never for a moment lose

sight of it, for otherwise

the third act will become

impossible, where it can and

ought to be the crowning

glory of the whole work (22

April 1914).

From now on the

points of contention grew ever

more detailed, each being

fought over with mounting

vehemence and tenacity.

Strauss demanded to know

whether Barak was to eat the

five little fishes or not:

they were, after all, equated

with the voices of the Unborn

Children. Hofmannsthal

responded by insisting on the

“wonderful smell of fish

frying in oil”, arguing that

this passage expressed a sense

of naïve delight. Strauss, who

approached the text from the

standpoint of rigorous logic,

clearly had difficulty making

sense of it:

What happens to

the shadow which the Dyer’s

Wife has lost in Act II and

which the Empress does not

want to accept? Surely the

Empress sings: “Ich will

nicht den Schatten", etc.

The shadow

therefore hangs in the air

[...] It would thus be most

important to have the

Empress once more, in Act

III expressly announce her

decision of renouncing the

bloodstained shadow (5 April

1915).

Hofmannsthal

delivered Act Three in April

1915, and although Strauss was

delighted with it, he

continued to harbour the same

reservations regarding the

logical construction of the

plot. The motives behind the

characters’ action, he went

on, should be more immediately

plausible and intelligible:

Your

third act is magnificent:

words, structure and

contents equally wonderful.

Only in its quest for

brevity it has become too

sketchy: for all the lyrical

moments: Duet between Barak

and Wife, the Nurse's exit

aria, duet between Emperor

and Empress, final quartet,

I definitely need more text.

No new ideas, just

repetitions of the same

ideas in different words and

at a higher pitch (15 April

1915).

Hofmannsthal

conceded the point:

Your musical

treatment of the Emperor is

for me the clearest possible

pointer how I am to deal

with this character in Act

III; after he is woken from

his petrification, he must

have his aria, his (totally

different) “Gralserzählung”

(14 May 1915).

Strauss remained a

hard taskmasten above all when

the point at issue was

operatic effectiveness and the

pace at which the music must

move:

Today I have a

request again: I am as

determined as ever to treat

the whole passage of the

Empress, after she has

caught sight of her

petrified husband until her

outcry “ich kann nicht”, as

a spoken passage.

Only I don’t want

to lose, as a tune, that

beautiful passage you wrote

for me additionally - and I

have now found a very good

place where I can fit it in

earlier. [...] Now the

former passage,

unfortunately, is very short

and is over so quickly that

it could do with

considerable expansion: just

before there is therefore a

wonderful opportunity for

inserting the great,

beautiful melody of “mit dir

sterben, auf, wach auf". You

would merely have to be good

enough to adjust it to the

slightly altered situation

by re-fashioning it again

(18July 1916).

Hofmannsthal sighed

and once again gave way. It

was not the last time that the

differences between him and

Strauss, who thought and

worked in a totally different

medium, were to surface:

It

is a great relief to me to

know that you intend to

reduce the last part of this

grave, sombre work to secco

recitative! Even so: are we

really to have yet another

spinning out of the original

passage? More and more! Must

that be? My dear Dr.

Strauss! [...] I enclose the

new text. But do remember:

once a melody seeks to

dominate the scene, and the

scene dominates the act,

instead of the other way

about, that is invariably

the beginning of the end (24

July 1916).

Primale parole,

dopo ... ?

These few excerpts

from the extensive

correspondence between

Hofmannsthal and Strauss show

how close the two

collaborators came on more

than one occasion to talking

at cross purposes.

Hofmannsthal was too much of a

poet, Strauss too much of a

musician for them to be able

to understand one another

fully. The sense of unease

caused by the impenetrability

of what Hofmannsthal termed

this “grave, soinbre work”

remained right up to the time

of the première. The poet

suggested preparing audiences

by means of an introduction to

the libretto. It was to have

been written by Max Mell, but

Mell failed to complete the

task in time, and so

Hofmannsthal himself took up

the gauntlet, producing an

outline of the opera’s

contents that turned out to be

far more than a mere synopsis

but is, rather a poetically

ambitious account of the

text’s many intertwined

motifs. And it is here, more

than anywhere, that we may

begin to fathom the reasons

why this opera is such a

tremendous challenge to

directors on the one hand and,

on the other, to listeners and

audiences attempting to follow

the piece and to empathise

with its characters.

The Empress is

caught up in a complex plot

that embroils her in guilt

although she has done no

wrong. She is not yet

indissolubly bound to

humankind. She has no shadow

in other words, she is

childless. (Just as our shadow

represents, as it were, an

extension of ourselves, so

children enable us to prolong

our lives beyond death.) The

symbol and what it symbolises

are interchangeable, sign and

concept coincide. In order to

prevent the Emperor from

turning to stone, the Empress

must acquire a shadow yet

here, too, there are problems

of understanding. Whg in fact,

is the Emperor threatened with

petrifaction? As a punishment

for forcibly turning a child

of the spirit world into a

human being? As a punishment

for his inhuman treatment of a

woman, whom he demeans by

reducing to an object of the

male instinct to pursue and

possess? It remains unclear

what the answer is, and it is

this psychoanalytical

ambiguity that makes the

libretto so puzzling.

The Nurse finds a

dissatisfied woman ready to

relinquish Iier shadow in

return for affluence and the

fulfilment of her physical

desires. The Empress thus

descends to the level of the

Dyer’s Wife and at the same

time gains an idea of human

dignity as a result of Barak’s

goodness. She finally becomes

human by voluntarily refusing

to have any truck with

adultery and infidelity and by

renouncing all thought of her

own happiness out of pity for

Barak and his wife.

What is so confusing

about this concept, in terms

of both the plot and the

characters themselves, is the

interchangeability of the

individual couples. On the one

hand, the Emperor and Empress

are the “high-born couple”

and, as such, represent the

opposite of the more

“lowlyborn” couple of Barak

and his wife. (To that extent,

it is entirely legitimate to

draw parallels with the two

couples in Die Zaubeflöte,

with the qualification, of

course, that in the trials

through which they have to

pass, Barak and his wife are

on exactly the same conceptual

and linguistic level as the

Emperor and Empress.) At the

same time, however, a chiastic

relationship exists between

the two couples, with the

rapaciously acquisitive and

possessive Emperor paired with

a Dyer's Wife willing to

renounce the proverbial joys

of giving in return for wealth

and the gratification of her

sexual instincts. Meanwhile,

the Empress - for much of the

opera apparently

altruistically concerned to

save her husband - is

obscurely related to Barak,

the altruistic philanthropist

who personifies pure love, a

love that is both

understanding and forgiving.

The Nurse has no such

counterpart: she is the

embodiment of evil pure and

simple and, to a certain

extent, an extension of

Keikobad. But the characters

all appear less clear-cut in

the libretto, since they are

so divided. The Dyer's Wife is

only half guilty: her sexual

obsessions are given free rein

only in her imagination.

However great her frustration

at what she regards as her

unfulfilled marriage, she

lacks the courage to take the

decisive step that would allow

her to break free. She lacks

the radicality of a Tosca or a

Lulu, a Marie or a Salome. In

the deeper layers of her

consciousness, she is a petit

bourgeois housewife. No less

striking are the

contradictions in the

psychological make-up of the

Empress, although in her case

they are the result of her

gradual development from

insecurity and ignorance to a

woman in full possession of

her intellectual and moral

powers. She develops from the

state of “having” to one of

“being” - to borrow terms from

Erich Fromm.

These few brief

remarks may suffice to

indicate why Strauss was bound

to have such problems with a

libretto of this kind. A

closer examination of the text

reveals a wealth of different

layers, each of which calls

into question the layers above

it. The composer simply came

up against a brick wall, a

solidly built divide, neatly

and thoughtfully erected, with

almost hermetically sealed

gaps between the bricks and

with nary a window or door in

sight.

The reasons for this are no

doubt to be sought in what

might be termed Hofmannsthal's

network of cultural

coordinates, with the poet

piling source upon source and,

on the basis of his wide

reading, compiling a libretto

thatis a compendium of

literary models. In the fifth

of the Thousand and One

Nights, Scheherazade

tells of the gazelle wounded

by a falcon. The hunchbacked

brother makes his appearance

on the thirty-first night, the

oneeyed brother on the

thirty-second. For fifty-four

nights, Scheherazade tells of

a jeweller who catches a

birdlike maiden and makes her

his wife. The magic fountain

of golden water gushes forth

on the 756th night, and on the

699th night the Emir Hasan

Sharr al-Tarik reproaches his

wife for her infertility.

The Grimm Brothers’

fairy-tales likewise served as

a source-book: in Rumpelstiltskin

we have the fatal deadline, in

Snow White the

desperate desire for a child,

and in Faithful Johannes

and The Two Brothers

we read of characters turned

to stone (the same motif of a

petrified prince occurs in the

eighth of Scheherazade's

tales). Comparisons with

Eduard Mörike`s Tale of

Fair Lau also come to

mind: here we are told how the

beautiful Lau is half human on

her mother's side. Nor should

we forget Adelbert von

Chamisso's Peter Schlemihl,

who gets into trouble when he

sells his shadow to the Devil.

According to popular belief,

the shadow is synonymous with

a man's soul and with his

inner life force. Even in the

New Testament, the Virgin Mary

is “overshadowed” - in other

words, impregnated - by the

Holy Ghost. In short, the

shadow can also mean the

promise of an m yet unborn

existence.

A further factor

here is Hofmannsthal's

lifelong obsession with the

problem of what he termed a

“fatal link” between the

generations. in Der Tor

und der Tod, it is the

hero's mother who first

upbraids her son for his

lifeless egocentricity; Die

Frau in Fenster

adumbrates Die Frau ohne

Schatten; and the motif

of the child is already found

in Der Kaiser und die Hexe.

Motherhood and magic, finally

are linked in Die Hochzeit

der Sobeide and Das

Bergwerk zu Falun.

These are by no means the only

sources on which Hofmannsthal

drew in fashioning his

libretto - he even quotes word

for word from the final scenes

of Parts One and Two of

Goethe's Faust, with

the Nurse, as a female

Mephistopheles, echoing the

latter’s peremptory “Hither to

me” - but they may serve to

indicate the range of literary

references with which the

libretto resonates. The

subject-matter bubbled up

beneath his hands and had to

be made more dense and

compressed. It is this - and

its motivic ambiguity - that

makes it so complex and so

unprecedentedly complicated.

Music as the Word’s

Disobedient Daughter

A glance at the

secondary literature on Die

Frau ohne Schatten

reveals the curious fact that

writers have given a wide and

embarrassed berth to analyses

of its music. The reasons for

this may be sought, perhaps,

in the music's relationship to

its disproportionately complex

text. Strauss's music may be

seen as an attempt to gain a

purchase on so impenetrable a

text and, where this is simply

not possible, to circumscribe

and draw a veil over its

complex literary forms. But

what does this music achieve -

in addition to its obvious

function of clothing the

characters, plot and scenes in

the most powerful, radiant and

glowing colours? In the first

instance, the music helps each

of the characters to express

him - or herself in his or her

own distinctive language,

ensuring that they emerge as

recognisable types. Strauss is

most successful at this in the

case of his two most extreme

characters, the Nurse and

Barak. A maliciously

mephistophelean figure, the

Nurse is typified by it

musical language located on

the very threshold of New

Music. She is denied an even

melodic line: instead, her

vocal writing is notable for

its wide intervallic leaps,

its rhythmic shifts and

extreme range. Equally

unstable is the harmonic

framework, which more than

once draws close to atonality.

Strident orchestral timbres,

eruptive dynamic contrasts and

sudden changes of tempo all

play their part here. The

Nurse's musical language

abounds in shimmering

chromaticisms, feverish

rhythmic restlessness, dynamic

instability and volatile

modulations, and it continues

to do so until she disappears

amid tempest, thunder and

lightning halfway through the

third and final act.

Musically, too, the Nurse is

intractable and immutable.

Diametrically

opposed to this is Barak's

musical world. His melodic

lines, in the main, are

diatonic, their rhythms based

on regular metres, their

harmonies solidly grounded on

clear-cut, tonal foundations.

Their melodic range is

relatively small: a man like

Barak does not get worked up.

He is even-tempered, losing

his composure only once, when

he is confronted by his wifes

apparent infidelity and he

steps outside his rhythmically

and metrically preordained

role. His vocal writing has a

woodcut-like simplicity to it,

occasionally approaching the

hymnlike tones of the three

Night-Watchmen’s chorale at

the end of the opening act,

not least when he broods on

women's capricious ways and

nevertheless retains his

composure (“Aber ich trage es

hart”).

There is a gulf,

too, between Barak and his

wife, a gulf that is fully

exposed in their opening

scene. As always, Barak is

gentle and resolute, his

progress through life

reflected in his four-square

musical values, notably in the

scene early in Act Two where

he feeds his brothers and the

beggar children. In contrast,

the musical gestures of his

wife are not unlike those of

the Nurse - irritable, highly

strung melodic prose, restless

rhythms and sudden and violent

changes of dynamics. Her

musical portrait is painted in

primary colours of passionate

hue, a passion that emerges

above all in her great duet

with Barak in Act Three

(“Barak, mein Mann”). Strauss

characterises her with

snatches of text punched out

with nervous haste and with

dramatic vocal lines,

tremulous tremolandos,

whipped-up tempos and

instrumental gestures that

suddenly flare up in the

orchestra, as the tempo grinds

to a halt, then abruptly

speeds up once again. In

contrast to this is Barak's

firm, resolute and

imperturbable melos, a

melodic ideal to whose

straightforwardness his wife,

too, slowly submits: it is

clear from the music that she

finally achieves the

longed-for transformation from

inner turmoil to the utter

certainty of her love for

Barak. The tone associated

with the Nurse is lost, as she

adapts her vocal line to suit

Barak's simple musical

characterisation.

The Empress, too,

undergoes a complete

transformation. She first

appears in the opening act as

a figure of light, an aspect

nowhere more apparent than in

her entrance aria, “Ist mein

Liebster dahin” The music

caresses her with its gentle

accompanying figures, its pure

harmonies and radiant

instrumental colours, but, as

the opera runs its course, it

undergoes an immense change

and comes to adopt a

completely different tone: her

great monologue in Act Three,

“Vater, bist du’s?”, initially

strikes a note of piety, then

of awakening life and

awakening passion. Musically

too, she becomes human, a

change that is finally

complete when she, too,

submits to Barak's simple

songlike tone. And it is the

Empress, finally, who retains

the right to utter the most

human of all sounds, the

tormented scream of a

suffering creature.

Musically speaking,

the Emperor remains the most

unremarkable figure, due to

his literary model. In his

opening scene, he strikes a

heroic note, but other

expressive devices take over

in the process of inner change

leading up to his great

monologue in Act Three, with

his vocal line assuming a more

organic quality; the writing

now becomes far less rigid and

more sinuous, the articulation

more lyrical and the tempi and

dynamics more sustained. The

Emperor, in short, acquires

gentler and more romantic

features.

With the exception

of the Nurse, all the

characters would appear to be

influenced by Barak's musical

language, a language that they

all progressively adopt in the

interests of a general musical

synthesis and that emerges, as

it were, as the opera's

underlying tone, embodying a

simplicity that ultimately

emanates from a single point

in the score, namely, the

visionary chorus of Unborn

Children whose vocal line,

innocence incarnate, is

permeated, on its first

appearance, with sighlike

falling semitones.

The music is not

only able to flesh out the

characters, it also paints

portraits of picturesque

power. For the confused Dyer's

Wife it evokes images of

“beauty beyond compare” with

its elegantly synaesthetic

themes, the Nurse's “alluring

offers" striking a highly

exotic note in the sparsely

furnished Dyer's hut. The

enchanted images of the five

little fishes conjured up by

the Nurse are likewise

pastel-shaded, much as the

apparition of the Young Man

spirited out of the air by the

Nurse is tenderly etched into

the imaginative world of a

woman's mind, suggesting both

radiance and fragrance. When

the scene changes to a

romantic landscape and the

Emperor calls out for his

falcon, Strauss uses velvety

brass textures to create a

series of tender sinuous

images of evocative immediacy.

And the listener can literally

hear the way in which it

gradually grows darker in

Barak's house in Act Two, in

much the same way that the

music descends into a

cacophonous hell of

cataclysmal force as Barak's

hovel collapses in ruins at

the end of the act. The

three-dimensionality of the

subterranean vault in Act

Three, the plunge into chaos,

the bubbling fountain of

golden water and the note of

transfiguring radiance on

which the opera ends - on each

occasion Strauss draws on

appropriate tone-painterly

devices to conjure up images

in the imagination of even

those listeners obliged to

forgo a production on stage.

Thirdly, the music provides

fluid transitions in the form

of transformation scenes. When

the Empress and Nurse descend

into the world of men in Act

One, the music depicts their

stormy flight in an orgy of

brutal discordancy - an

example of programme music on

the operatic stage that is

repeated in Act Two when the

scene changes from Barak's

hovel to the Emperor's hunting

reserves and, later, to the

falconer's house, whither

nightmare-like music bears the

Empress. In keeping with the

fairy-tale tone of

Hofmannthal's scenario, these

fluid transitions seem, as it

were, to cross-fade and, at

the same time, to fulfil an

anticipatory function: it is

already clear from the music

here that the Empress's sleep

will be disturbed. The sinking

of the vaulted rooms, the

parting of the clouds, the

rocky terrace and the dark

sound of rushing water - all

these stage-directions are

acted out in the music, with

Strauss's transformation music

describing the events that are

taking place with graphic

intensity and immediacy.

Fourthly, the music

helps listeners to find their

way round the score, which it

does by means of numerous

leitmotifs in the manner of

those found in Wagner's Ring.

Keikobad, the falcon, the

falcon's prophecy, the human

shadow, the Unborn Children -

such motifs invariably put in

an appearance where it makes

sense for them to do so and

where they can create a

network of interrelationships.

“Invocations were made to

mighty names,” sings the Nurse

and immediately we hear

Keikobad's motif, just as we

do when the Dyers' Wife

exclaims that a mule can walk

along the brink of an abyss,

untroubled by its depths and

by its mystery: the mystery

the music tells us, is the

evil mystery of Keikobad. At

each point in the score, the

music is better informed than

the characters on stage. Just

as Wagner intended, the music

is a kind of Greek chorus that

comments upon the action.

Space does not allow

us to do more than sketch out

these various functions of the

music, but even this brief

summary may help to throw

light on a score in which,

with the best will in the

world, it is hard to find any

conventionally “beautiful”

passages. Indeed, it may

not contain such pmsages since

the poetic complexity of the

text presupposes a similar

degree of musical complexity

in the form of a network of

motivic, gestural and

descriptive coordinates. The

music does not end merely in

order to start up again

afresh: rather each musical

phrase flows seamlessly into

the next. Vocal styles are

progressively transformed. The

orchestra assumes the role of

a commentator, demanding

cognitive understanding rather

than guaranteeing affective

enjoyment.

It is this that

makes the opera such a “grave,

sombre work” (to quote from

Hofmannsthal's letter of 24

July 1916) and one which, as

the librettist admitted in his

letter of 15 May 1911, he

would rather have staged

without any music at all. Seen

in the cold light of day, Die

Frau ohne Schatten is

the work of two ambitious

professionals, two highly

educated individuals who had

set themselves the goal of

creating a work of art, while

allowing no scope for simple

theatrical instinct. Although

it would be wrong to conclude

from this that the piece is

merely brain-spun, it would

also be misleading to claim it

as an example of a work

inspired by the naïvety of a

narrative art appropriate to

the stage. In painting a

musical portrait of Barak as a

quasi-bourgeois, God-fearing

and strong-minded type,

Strauss failed to reflect the

linguistic patterns of simple

folk in the way that

Humperdinck, for example, was

able to do in Hänsel und

Gretel, Barak's musical

language is the product of a

highly developed way of

thinking that makes every

attempt to express itself in

simple terms. The problem of

understanding Die Frau

ohne Schatten - and the

same problem bedevils all

efforts to stage the work - is

that it has to come alive

without the assistance of

theatrical naïvety. The

offspring of this marriage

between two intellectuals was

a musically recalcitrant

child, a vocal symphony of

gigantic proportions, whose

wealth of musical images,

dense network of leitmotifs

and kadeidoscopically

colourful world of sound

conjures up fairy-tale scenes

inside the listeners head,

scenes not so easily recreated

on the boards of real-life

opera houses. Die Frau

ohne Schatten stands at

a point in the development of

music theatre at which the

theatre's limited means of

representation are transcended

and where, as a result of the

workings of a highly

sophisticated artistic

imagination, a world of

boundless fantasy opens up.

Hans-Christian

Schmidt

(Translation: Stewart

Spencer)

|

|

|