|

|

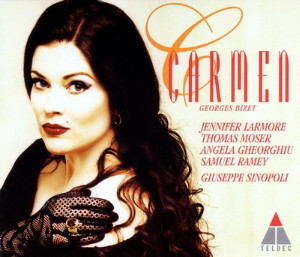

DG - 3

CDs - 0630-12672-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

.jpg) |

| DG - 1

CD - 3984-21771-2 - (c) 1998 |

|

| Georges

BIZET (1838-1875) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carmen |

|

158' 01" |

|

| Opéra Comique en

trois acte d'après la nouvelle

de Prosper Mérimée |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

53'

56" |

|

|

|

1.

Prélude |

3' 29" |

|

*

|

| PREMIER ACTE

|

N° 1:

Introduction: |

2.

"Sur la place chacun passe" (Les

soldats, Moralès)

|

2' 02"

|

|

|

|

|

3. "Regardez donc

cette petite" (Moralès, Les

soldats, Micaëla) |

4' 03" |

|

|

|

N° 2: Marche et

Choeur des gamins:

|

4.

"Avec la garde montante" [Mélodrame]

(Choeur des gamins) |

2' 21"

|

|

|

|

|

5.

"Halte! Repos!" (Zuniga,

Moralès, Don José) |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

|

6.

"Et la garde descendante" (Choeur des

gamins) |

1' 28"

|

|

|

|

|

7.

"Dites-moi, brigadier" (Zuniga,

Don José) |

0' 41" |

|

|

|

N° 3: Choeur et

Scène: |

8.

"Voici la cloche qui sonne" / "La

cloche a sonné" (Don José, Les

jeunes gens, Les soldats, Les

cigarières) |

2' 26" |

|

* |

|

|

9.

"Dans l'air, nuos suivons la fumée"

(Les cigarières, Les jeunes gens) |

2' 50" |

|

* |

|

|

10.

"Mais nous ne voyons pas la

carmencita" (Les Soldats, Les

jeunes gens) |

0' 41" |

|

|

|

|

11.

"Quand je vous aimerai?" (Carmen) |

0' 26" |

|

|

|

N° 4: Havanaise: |

12.

"L'amour est un oiseau rebelle" (Carmen,

Choeur) |

4' 21" |

|

* |

|

N° 5: Scène |

13.

"Carmen! sur tes pas nous nous

pressons tous" (Les jeunes gens,

Les cigarières) |

2' 05" |

|

|

|

|

14.

"Quelle effronterie!" (Don José,

Micaëla) |

0' 17" |

|

|

|

N° 6: Duo |

15.

"Parle-moi de ma mère!" (Don

José, Micaëla) |

1' 30" |

|

* |

|

|

16.

"Votre mère avec moi sortait de la

chapelle" (Micaëla, Don

José) |

2' 15" |

|

* |

|

|

17.

"Ma mère, je la vois!" (Don

José, Micaëla) |

1' 01" |

|

* |

|

|

18.

"Qui sait de quel démon j'allais

ȇtre la proie!" (Don José, Micaëla) |

4' 41" |

|

* |

|

|

19.

"Attends, je vais finir sa lettre" (Don

José, Micaëla) |

0' 33" |

|

|

|

N° 7: Choeur |

20.

"Au secours!" (Les cigarières,

Zuniga, Les soldats) |

4' 02" |

|

|

|

|

21.

"Maintenant que nous avons un peu de

silence" (Zuniga, Don José) |

0' 22" |

|

|

|

N° 8: Chanson et

Mélodrame |

22.

"Avez-vous quelque chose à répondre"

/ "Tra la la la..." (Zuniga,

Carmen) |

3' 33" |

|

|

|

|

23.

"Où me conduirez-vous?" (Carmen,

Don José) |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

N° 9: Chanson

[Séguedille] et Duo |

24.

"Près des remparts de Séville" (Carmen,

Don José) |

4' 35" |

|

* |

|

N° 10: Finale |

25.

"Voici l'ordre" (Zuniga, Carmen) |

2' 28" |

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

43'

19" |

|

|

|

1.

Entracte |

1' 44" |

|

|

| DEUXIÈME

ACTE |

N° 11: Chanson: |

2.

"Les tringles des sistres tintaient"

(Carmen, Frasquita, Mercédès) |

5' 08" |

|

* |

|

|

3.

"Vous avez qualque chose à nous

dire" (Zuniga, Pastia, Mercédès,

Frasquita, Carmen) |

1' 03" |

|

|

|

N° 12: Choeur et

Ensemble:

|

4.

"Vivat! vivat le toréro!" (Choeur,

Zuniga, Mercédès, Andrès,

Frasquita, Pastia) |

1' 33" |

|

|

|

N° 13: Couplets

[Air du Toréador]: |

5.

"Votre toast, je peux vous le

rendre" (Escamillo, tous) |

4' 40" |

|

* |

|

|

6.

"Messieurs les officiers, je vous en

prie!" (Pastia, Zuniga,

Escamillo, Carmen) |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

N° 13bis: Choeur:

|

7.

"Toréador, en garde!" (Choeur) |

1' 07" |

|

* |

|

|

8.

"Pourquoi étais-tu si pressé" (Frasquita,

Pastia, Le Dancaïre, Mercédès, Le

Remendado) |

0' 35" |

|

|

|

N° 14: Quintette: |

9.

"Nous avons en tête une affaire" (Le

Dancaïre, Frasquita,

Mercédès, Le Remendado,

Carmen) |

4' 56" |

|

|

|

|

10.

"En voilà assez!" (Le

Dancaïre, Le

Remendado,

Frasquita,

Carmen,

Mercédès) |

0' 36" |

|

|

|

N° 15: Chanson: |

11.

"Halte-là! Qui va là?" (Don

José) |

0' 37" |

|

|

|

|

12.

"C'est un dragon, ma foi" (Mercédès,

Frasquita, Le

Dancaïre,

Carmen) |

0' 21" |

|

|

|

|

13.

"Halte-là! Qui va là?" (Don

José) |

0' 44" |

|

|

|

|

14.

"Enfin... te voilà" (Carmen, Don

José) |

0' 45" |

|

|

|

N° 16: Duo: |

15.

"Je vais danser en votre honneur"

[Air de la Fleur] (Carmen, Don

José) |

5' 55" |

|

|

|

|

16.

"La fleur que tu m'avais jetée" (Don

José, Carmen) |

3' 44" |

|

* |

|

|

17.

"Non! tu ne m'aimes pas!" (Carmen,

Don José) |

3' 46" |

|

* |

|

N° 17: Finale: |

18.

"Holà! Carmen! Holà, holà!" (Zuniga,

Don José, Carmen, Le Remendado, Le

Dancaïre, Les

bohémiens) |

3' 32" |

|

|

|

|

19.

"Suis-nous à travers la campagne" (Frasquita,

Mercédès, Carmen, Le Remendado, Le

Dancaïre, Les bohémiennes, Don

José) |

1' 42" |

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 3 |

|

60'

46" |

|

|

|

1.

Entacte |

3' 18" |

|

|

|

|

Premier

Tableau

|

|

|

|

| TROISIÈME

ACTE

|

N° 18:

Introduction:

|

2.

"Ecoute, compagnon, écoute!" (Les

contrebandiers, Frasquita,

Mercédès, Carmen, Don José, Le

Dancaïre, Le

Remendado) |

4' 13" |

|

|

|

|

3.

"Reposons-nous une heure ici" (Le

Dancaïre, Don

José, Carmen) |

0' 51" |

|

|

|

N° 19: Trio:

|

4.

"Melons! Coupons!" (Frasquita,

Mercédès) |

3' 21" |

|

|

|

|

5.

"Carreau! Pique! ... La mort!" (Carmen) |

3' 03" |

|

* |

|

|

6.

"Parlez encore, parlez, mes belles"

(Frasquita, Mercédès, Carmen) |

0' 47" |

|

* |

|

|

7.

"Eh bien? ... nous avons aperçu" (Carmen,

Le

Dancaïre,

Mercédès, Le

Remendado,

Frasquita, Don

José) |

0' 29" |

|

|

|

N° 20: Morceau

d'Ensemble:

|

8.

"Quant au douanier, c'est notre affaire!"

(Frasquita, Mercédès, Carmen, Les

bohémiennes, Les bohémiens, Le

Dancaïre, Le Remendado) |

3' 07" |

|

* |

|

|

9.

"Ah, enfin, nous y sommes" (Le

guide, Micaëla) |

0' 19" |

|

|

|

N° 21: Air: |

10.

"Je dis que rien ne m'épouvante" (Micaëla) |

4' 59" |

|

* |

|

N° 22: Duo:

|

11.

"Qui êtes-vous? Répondez" - "Je suis

Escamillo, toréro de Grenade" (Don

José, Escamillo) |

5' 23" |

|

|

|

N° 23: Finale:

|

12.

"Holà! holà! José!" (Carmen,

Escamillo, Le Dancaïre, Don

José, Les contrebandières, Les

contrebandiers) |

2' 50" |

|

|

|

|

13.

"Halte! quelqu' un est là" (Le

Remendado, Carmen, Le Dancaïre, Don José, Micaëla,

Choeur) |

5' 52" |

|

|

|

|

14.

Entracte |

2' 14" |

|

* |

|

|

Deuxième

Tableau |

|

|

|

|

N° 24: Choeur:

|

15.

"A deux cuartos" (Les

marchandes, Les marchands, Zuniga,

Andrès, Un bohémien) |

2' 18" |

|

* |

|

|

16.

"Qu' avez-vous donc fait de la

Carmencita?" (Zuniga, Frasquita,

Andrès, Mercédès) |

0' 38" |

|

|

|

N° 25: Choeur et

Scène:

|

17.

"Les voici! Vinci la quadrille" (Les

enfants, choeur) |

3' 45" |

|

* |

|

|

18.

"Si tu m'aimes, Carmen" (Escamillo,

Carmen) |

1' 25" |

|

|

|

|

19.

"Place! place! au Seigneur Alcade!"

(Quatre Alguazils, Les enfants,

Choeur, Frasquita, Carmen,

Mercédès) |

2' 19" |

|

|

|

N° 26: Duo finale: |

20.

"C'est toi!" - "C'est moi!" (Carmen,

Don José) |

5' 42" |

|

* |

|

|

21.

"Viva! la course est belle!" (Choeur,

Don José, Carmen) |

3' 54" |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jennifer LARMORE,

CARMEN, une bohémienne |

CHOR DER BAYERISCHEN

STAATSOPER |

|

| Thomas MOSER, DON

JOSÉ, un brigardier |

Udo Mehrpohl, Chorus

master |

|

| Angela GHEORGHIU,

MICAËLA, une jeune paysanne |

KINDERCHOR DER BAYERISCHEN STAATSOPER |

|

| Samuel RAMEY, ESCAMILLO,

un toréro |

Eduard Asimont, Chorus

master |

|

Nathalie BOISSY,

FRASQUITA, bohémienne

|

BAYERISCHES

STAATSORCHESTER |

|

| Natascha PETRINSKY,

MERCÉDÈS, bohémienne |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

| Maurizio MURARO,

ZUNIGA, un lieutenant |

Dialogue adaptation,

Language coach & musical assistant:

Janine Reiss |

|

| Jean-Luc CHAIGNAUD,

MORALÈS, un brigardier |

Musical coach: Donald

Wages |

|

| Jan ZINKLER, LE

DANCAÏRE, contrebandier |

|

|

| Ulrich REß, LE

REMENDADO, contrebandier |

|

|

| Gintares WYSNIAUSKAS,

ANDRÈS, un lieutenant |

|

|

| Ulrike UHLMANN,

UNE MARCHANDE |

|

|

| Dieter MISERRE,

UNE BOHÉMIEN |

|

|

| Nicolas TREES, LILLAS

PASTIA, le tenancier de taverne |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Stadthalle,

Germering (Germania) - dicembre

1995 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

producer

|

|

Renate

Kupfer |

|

|

Recording

producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

engineer |

|

Jens

Schünemann, Tobias Lehmann |

|

|

Digital editing |

|

Stefan

Witzel, Jens Schünemann |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

-

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Teldec |

0630-12672-2 | LC 6019 | 3 CDs -

53' 56". 43' 19" & 60' 46" |

(p) 1996 | DDD

Teldec

| 3984-21771-2 | LC 6019 | 1 CD -

76' 13" | (c) 1998 | DDD |

Highlights *

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE OPERA'S

GENESIS AND FIRST

PEFORMANCES

I have just been

ordered to compose three

acts for the Opéra Comique.

Meilhac and Halévy are doing

my piece" - so runs the

first brief reference to Carmen

in Bizet's

correspondence.Henri Meilhac

was also known as a

cartoonist, while Ludovic

Halévy had a full-time job

at the Ministry of the

Interior and in the Algeria

Office. Their other

collaborations include not

only Offenbach's La

belle Hélène and La

vie parisienne but

also the original scenario

for Johann Strauß’s Die

Fledermaus. They made

numerous changes to Mérimées

short story in an attempt to

tone down the character of

Carmen and make her more

suitable to the operatic

stage, turning the common

prostitute into a “normal”

woman, a transformation that

ultimately constituted a far

greater assault on society.

They invented the character

of Micaëla and, with her,

the idea of domestic

happiness, conceiving her as

the embodiment of chaste and

steadfast love and, as such,

a foil to Carmen. Although

the figure of Escamillo is

to be found in Mérimée, he

is no swaggeringly

successful bullfighter. The

librettists also added the

usual stock-in-trade of opéra

comique, including

street urchins, smugglers

and the chorus outside the

bullring. All these

characters are related to

their counterparts in

Offenbach's operettas, which

are likewise peopled with

smugglers and robbers,

soldiers and women of easy

virtue; only Bizet’s music

has invested them with

individuality. Like the

composer, Meilhac and Halévy

never visited Spain, but

they used a whole series of

authentic sources, chief of

which were contemporary

travelogues by writers such

as Théophile Gautier and

Alexandre Dumas père

and engravings by Gustave

Doré and others, all of

which served as concrete

models in drafting the

scenario and dialogue. Some

of the words, including

those of the Habanera, are

by Bizet himself.

Although Carmen

is now one of the most

widely performed of all

operas, its first

performance on 3 March 1875

was a flop. Halévy described

his impressions of the first

night in a hurried letter to

a friend written on the

morning after the

performance, allowing us to

recapture something of the

mood of that occasion:

"Act

I well received.

Galli-Marié's first song

applauded, also the duet

for Micaëla and José. End

of the act good -

applause, singers called

back on stage. A lot of

people on stage after this

act. Bizet surrounded and

congratulated. The second

act less fortunate. The

opening very brilliant.

Great effect from the

toreador's entry, followed

by coldness. From that

point on, as Bizet

deviated more and more

from traditional form of opéra

comique, the public

was surprised,

discountenanced perplexed.

Fewer people round Bizet

between the acts.

Congratulations less

sincere, embarrassed,

constrained. The coldness

more marked in the third

act [scene one]. The only

thing applauded was

Micaëla's air, of old

classical cut. Still fewer

people on stage. And after

the fourth act [third act,

scene two], which was

glacial from first to

last, no one at all except

three or four faithful and

sincere friends of

Bizet's. They all had

reassuring phrases on

their lips but sadness in

their eyes. Carmen

had failed."

The reasons fo

this failure were due as

much to the subject matter

as to the music. Even before

the first night, there had

already been criticism of

the allegedly "immortal"

action and its cast of

smugglers and cigarette

makers. Particular obloquy

was reserved for the final

scene, in which the heroine

is murdered on stage.

Moreover, Bizet himself was

the subject of immoderately

high and irreconcilable

expectations. It was said

that he would either restore

opéra comique to its

former glory or that he

would adopt a grand

Wagnerian manner. In the

event, he confounded both

these expectations by

picking up the tradition of

French opéra comique

and developing it by

combining it with social and

emotional realism. The

critics had a field-day,

accusing the composer of

immorality and claiming that

the score lacked order,

planning and clarity and

that the subject matter was

unsuited to the theatre.

None the less, the work had

already been performed no

fewer than thirtythree times

by the date of Bizet’s

sudden death on 3 June 1875,

the charge of immorality

merely serving to add to the

opera's appeal. Carmen

was given forty-eight times

during the 1875/76 season,

but then disappeared from

the Paris repertory for many

years, not returning to the

composer's native city until

its success had been assured

by a number of productions

abroad.

VERSIONS OF

THE OPERA

Carmen

belongs to the French opéra

comique tradition, in

which arias and ensembles

are interspersed with spoken

dialogue. (A similar feature

may be found in German

Singspiels such as Mozart's

Die Entführung aus dem

Serail and Die

Zauberflöte.) For the

first Viennese production of

the work in October 1875 (in

other words, after the

composer's death), Ernest

Guiraud, a friend of

Bizet's, replaced the spoken

dialogue with recitatives,

while at the same time

taking the opportunity to

cut portions of the text. He

also altered the

instrumentation and even

interpolated a ballet. His

recitatives reveal an

embryonic leitmotif

technique clearly designed

to turn the work into a grand

opéra and to transform

what had been a light opéra

comique, with its

relatively comic tone, into

an emotionally heavyweight grand

opéra. (A number of

Offenbach’s works are

likewise termed opéras

comiques.) Not until

1906 did Hans Gregor restore

the spoken dialogue for a

production in Berlin. Walter

Felsenstein's 1949

production was only one of

many attempts to provide a

new German translation of

the work, but even he had

difficulty establishing an

authentic version, since not

even the first French

printed edition of the vocal

score is identical in every

respect with Bizet's

autograph sources.

It was not until

much later that the

conducting score used at the

first performance was

rediscovered, revealing that

no fewer than 71 sides of

the score had been pasted

over or stitched together

while at the same time

enabling scholars to tell

which changes to the

instrumentation and

performance markings such as

tempo had been made by Bizet

himself and which had been

introduced subsequently.

Fritz Oeser’s “Critical New

Edition Based on All

Existing Sources” was

published in 1964 and

immediately caused an outcry

not least because other

musicologists placed a

different interpretation on

the sources. Moreover it is

now virtually impossible to

say which cuts and additions

were instigated by Bizet

himself, which were merely

concessions to particular

singers or to the

circumstances surrounding

the first production, and

which should be regarded as

being of lasting

significance.

For Giuseppe

Sinopoli, Fritz Oeser’s

great merit lies in his

“having had the courage

after all these years to

come up with a critical

edition based on Bizet's

original sources. My own

particular aim was to

perform everything just as

Bizet wanted it. All the

cuts that are so often

undertaken result in a piece

that is neither simpler nor

more beautiful nor more

logical than Bizet’s

original, but in reality

detract from it. What is

lost in this way are often

small details, nuances, a

slightly different

perspective or a brief

retrospective glance which

is, however of great

interest and dramaturgically

justified. Bizet's original

is a precise and implacable

dramatic run-through, the

result of a sincere desire

to reflect and brood on the

way in which a story like

Carmen's could come about.”

LOVE THAT ENDS

IN DISASTER

For all its

folklore and local colour, Carmen

is ultimately about the

conflict between two people

who love each other and in

doing so cause each other

pain and disillusionment - a

love, in short, that ends in

disaster. Carmen is

one of the first operas not

to include in its cast-list

any characters from the

upper echelons of society:

the conflicts are not due to

any social factors but stem

from an unavoidable clash of

emotions.

For José, Carmen

is a femme fatale,

he describes her as a witch,

a demon and even as a devil.

He thinks she has magic

powers. Whether or not this

view of Carmen is rooted in

superstition or in his

general fear of women, it

leads to his losing his

direction in life and

ultimately to his moral

collapse. José is afraid of

Carmen and of the force of

her femininity. And Carmen

certainly uses her sexuality

in a calculating way. But it

remains doubtful whether we

can really call her a femme

fatale. She does not

intentionally cause ]osé’s

downfall but defines her own

space and insists on her

freedom. Carmen is both

instigator and victim at one

and the same time. She is

introduced as an object of

male desire: she sings and

dances for men, is used by

Lillas Pastia to drum up

trade and helps the

smugglers by distracting

customs officers and

soldiers with her physical

charms. But she also tries

to break out of this role

and to protect herself from

men. Her Habanera is an

expression of her

philosophy: her love cannot

be obtained by threats or

cajolery. “If you don’t love

me, I love you, and if I

love you, beware!” The men

she wants are precisely

those who do not immediately

lust after her José

initially appears

unimpressed and, as such,

represents a challenge. Only

when he is so much in love

with her that he is willing

to suffer degradation and

imprisonment on her account

is she herself impressed.

But later he begins to bore

her and she drops him

without a moment's

hesitation, not least

because he is not prepared

to subordinate his duties as

a soldier to his love for

her. In the end Carmen

chooses death, literally

provoking José into killing

her.

In turn, José

expects too much of Carmen

with his insistence on

possessing her to the

exclusion of all else. He

fails to understand her true

nature. Don José is an

impoverished member of the

rural aristocracy who gives

the impression of being a

mother-fixated petty

bourgeois dreaming of

domestic bliss. He is

perfectly well aware that he

could find such happiness

with Micaëla, the submissive

and naïve country girl, but

makes no attempt to pursue

this line of least

resistance. The feelings

that draw him to Carmen -

first love, then hatred -

are stronger Walter

Felsenstein once described Carmen

as “a string of confused

relationships”:

Micaëla loves José, José

loves Carmen, Carmen loves

Escamillo, and Escamillo

loves no one but himself.

THE MUSIC

Carmen

is a typical opéra

comique, even if this

fact may have become

obscured as a result of

adaptations of the score

that have long been common

currency. Not even the

tragic dénouement in the

form of Carmen's murder is

at odds with this tradition:

the term opéra comique

has little to do with the

English word "comic" and

rather more to do with

Balzac's comédie humaine.

Moreover, there had been

examples of opéras

comiques with tragic

endings even before Bizet.

Typical of the genre is the

use of spoken dialogue

between the musical numbers,

and the realistic way in

which music is pressed into

service: the march of the

street urchins in Act One,

the Habanera, Seguidilla and

Carmen’s song in Act Two

with its castanet

accompaniment and trumpet

calls in the background are

all realistic numbers that

could equally well be found

as incidental music in a

play. Alongside these, there

are of course arias,

ensembles and choral

numbers, but astonishingly

few of them are typically

operatic in style. All,

moreover, are legitimised by

the action.

Music’s affinities

with dance add a further

dimension here: in Carmen,

music is often an expression

of the whole body, not just

of the voice. Even the

overture already

encapsulates the opera's

basic conflict, the music

associated with the

bullfight being offset by a

dramatic motif in D minor

that ends abruptly in

adissonance and that can be

regarded as expression of

Carmen's rebellious nature

and desire for freedom. In

the rest of the work, too,

lyrical and dramatic

elements are interwoven with

others of a more folklike

character. Yet all are

related to the action and

are never used for their own

sake. The choice of

particular leitmotifs, the

sophisticated use of dynamic

markings and the rhythmic

design of the piece are

likewise all subservient to

the overriding drama. Even

the Introduction to Act One

is a classic example of

Bizet's mastery in terms of

its basic mood and

appropriateness to the

action: beginning with a

musical portrait of the

strolling crowd, it almost

allows the listener to feel

the Spanish sun beating down

before introducing us to

Micaëla, who, initially

afraid, mischievously adopts

the soldiers’ teasing tone

before slipping away "like a

bird", her escape clearly

audible in the orchestra.

Carme's Seguidilla

is an example of a typically

Spanish dance, whereas the

habanera is Cuban in origin,

the flamenco of gypsy

provenance. With its

descending scale ending on

the dominant, the Fate motif

recalls Andalusian music, in

which oriental influence is

unmistakable. Yet Carmen

does not claim to be a

faithful musical portrait of

Spain. In Bizet`s day,

Spanish music was something

of a fashionable phenomenon

and, like Hungarian music,

was used by many composers

to add spice to their

musical language. One thinks

in this context of works

such as Glinka's Spanish

Overtures, Rimsky-Korsakov's

Capriccio espagnol,

Sarasate's Spanische

Tänze, Lalo’s Symphonie

espagnole, Chabrier's

España and Debussy’s

Ibéria. It was not

until much later that

composers such as Ravel

(himself half-Basque in

origin), Falla, Albéniz and

Granados wrote music with

which the Spanish themselves

could identify.

Andreas Richter

(Translation:

Stewart Spencer)

|

|

|