|

|

DG - 2

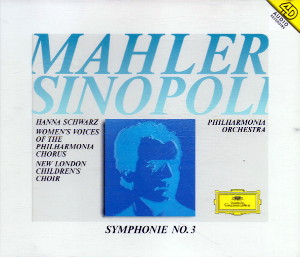

CDs - 447 051-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 3 |

|

99' 23" |

|

Compact Disc 1

|

|

61'

23" |

|

| ERSTE

ABTEILUNG |

|

|

|

| -

1. Kräftig. Entschieden |

32' 21" |

|

|

| ZWEITE

ABTEILUNG |

|

|

|

| -

2. Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig |

10' 41" |

|

|

| -

3. Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast |

18' 21" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

38'

00" |

|

| -

4. Sehr langsam. Misterioso.

Durchaus ppp "O Mensch! Gib

acht!" (Alt-Solo) |

11' 04" |

|

|

| -

5. Lustig im Tempo und keck im

Ausdruck "Bimm bamm! Es sungen drei

Engel einen süßen Gesang" (alt-Solo,

Frauen- und Knabenchor) |

4' 04" |

|

|

| -

6. Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden |

22' 58" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hanna SCHWARZ,

Alt/contralto |

WOMEN'S VOICES OF

THE PHILHARMONIA CHORUS |

|

|

NEW LONDON

CHILDREN'S CHOIR |

|

|

David Hill, Chorus

Master |

|

|

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

|

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All

Saints' Church, Tooting, London

(Gran Bretagna) - gennaio/febbraio

1994

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

Producer

|

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer)

|

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Hans-Rudolf

Müller |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 447 051-2 | LC 0173 | 2

CDs - 61' 23" & 38' 00" | (p)

1995 | 4D DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mahler’s Third

begins in unambiguously

rousing fashion: the first

theme, marked "forceful,

peremptory",

is played by eight horns in

unison, and in his sketches

Mahler termed it "Der

Weckruf",

or "Reveille".

The bold brash sound makes

it clear that large

instrumental forces will be

involved, but the theme can

also be heard as a signal of

another kind: its close

resemblance to one of the

student songs used by Brahms

in his Academic Festival

Overture proclaims

that Mahler’s symphonic

“festival” will be defiantly

unacademic; that models of

Brahmsian formal rectitude

will be swept away in a

torrent of Nietzschean

abandon.

This arresting opening is

not where Mahler began his

composition of the symphony:

in fact, the huge first

movement (or Part I, with

the remaining five movements

forming Part II)

was Written last, even

though one of its main ideas

was sketched out at an early

stage of the worlds genesis.

Yet the fact that music

which, for the listener,

prepares the ground for the

work as a whole was, for the

composer, as much a response

to what follows as a

preparation for it, goes to

the heart of the symphony’s

remarkable range of

expression as well as its

pervasive ambiguity, its

tendency to question the

very things it asserts with

such confidence.

Mahler claimed for the

symphony as a whole “the

same scaffolding, the same

basic ground-plan, that you’ll

find in the works of Mozart

and, on a grander scale, of

Beethoven”; at the same

time, however, his sequence

of movements is not that of

Mozart or Beethoven, and he

was

clear that “the variety and

complexity within

the movements is greater”.

Mahler was right to conclude

that the symphonic principle

could survive changes in the

classical order and number

of movements, especially if,

as some commentators would

claim, the greater length

and more intense

expressiveness of themes

that are often more songlike

or folklike than those used

by the Classical masters are

not necessarily to be

equated with greater

complexity. Complexity and

ambiguity tend to arise in

Mahler from the competing

claims of the “purely

musical” and the “primarily

programmatic”,

and the Third Symphony is a

fine demonstration of how

that competition can achieve

a compelling and ultimately

coherent - if not

conventionally integrated -

form.

When Mahler completed it, in

1896, he was 36 and well

launched on a career that

divided his energies between

conducting (with much

administrative

responsibility) and

composing. His reading of

Nietzsche encouraged an

uncompromising response to

political and cultural

issues of the day, while

demanding a metaphysical

context in which the epic

struggle between Apollo and

Dionysus was eternally

played out. Mahler did not

expect the work to win easy

success, not least because

it moved so decisively

beyond his two earlier

symphonies: “It

soars above that world of

struggle and sorrow and

could only have been

produced as a result of

them.” Conceived as a

celebration of the “happy

life” attained in the Second

Symphony’s triumphant

conclusion, it was

originally planned as a

sequence of seven responses

to aspects of nature and

humanity progressing to an

image of childlike

innocence. That ending would

be employed a few years

later in the Fourth

Symphony. In

ending the Third with a

finale of serene

expansiveness, and a vision

of love that goes well

beyond the childlike, Mahler

created the need for a

substantial, much more

earthy initial complement to

the finale’s sublimity. The

sense, in the final design,

of progression from rampant

natural forces (Part I)

through more civilizing

natural and social

circumstances to

transcendent spiritual

fulfilment remains true to

the generative idea of the

“happy life”, yet also

preserves the tension

between a radical desire for

greater social progress and

purely spiritual

aspirations.

Part I comprises an

Introduction - "Pan

awakes" - and the first

movement proper - "Summer

marches in (Bacchic

procession)". Mahler

wrote of a process in which

a “captive life struggling

for release from the

clutches of lifeless, rigid

Nature... finally breaks

through and triumphs”,

and the essentially earthly

concerns of this music are

clear from his confession

that “the entire thing is

unfortunately... tainted

with my disreputable sense

of humour”. He also said

that the opening “will be

just like the military band

on parade. Such a mob is

milling around, you never

saw anything like it”. As

“satyrs and other such rough

children of nature disport

themselves”,

winter is driven out “and

summer, in his strength and

superior power, soon gains

undisputed mastery”.

The first movement can be

seen as a gigantic

commentary on traditional

sonata-form design and,

although such a radical

reinterpretation of a

hallowed model continues to

provoke widely contrasted

responses, the structure and

the material of Part I are

entirely appropriate to the

work’s large purpose:

humanity can and must

explore nature as both

benign and threatening, and

human nature can believe

itself capable of the

highest fulfilment, even

when aware of the midnight

bell’s message that neither

summer nor life itself last

for ever.

In

Part Il of the symphony,

perspective and scale shift

substantially, without

destroying either ambiguity

or coherence. “What the

flowers in the meadow tell

me” may be a graceful

Minuet, but, as Mahler

noted, “the mood doesn't

remain one of innocent,

flower-like serenity”. Even

in summer there are storms

and, at the end, a mood

tinged with regret for what

must pass. To shift from Minuet

to Scherzando (“What the

animals in the forest tell

me”) is to intensify the

contrasts. This movement,

Mahler wrote,

“is at once the most

scurrilous and most tragic

there ever Was” and “there

is such a gruesome, Panic

humour in it that one is

more likely to be overcome

by horror than laughter”.

References to Mahler’s

setting of a Wunderhorn

poem about the cuckoo’s

death are lighthearted

enough, but the emergence of

a distant posthorn call is

an intrusion, initially

serene, that turns the mood

towards an increasingly

unstable aggressiveness.

Clearly, it is time for a

direct human response to

nature’s apprehensive

exuberance.

Movement No. 4, “What Man

tells me”, gives verbal form

to the work’s most

fundamental ambiguity. Nietzsche’s

verse juxtaposes sorrow and

joy, while the music’s

oscillation between minor

and major, and its

restrained, rapt

atmosphere, embody the

perception that joy is as

inseparable from sorrow as

life is from death. No. 5,

“What the angels tell me”,

declares that the love of

God will bring heavenly joy,

and

the music refers to the song

“Das himmlische Leben”,

later used to end the Fourth

Symphony. As a simple

solution to the problems of

humanity this may be

deemed dreamlike, or simply

a fantasy - a subversive

equation between religious

faith and childishness

which is at the furthest

remove from the Bacchic yea-saying

of Part I.

To redress the balance, No,

6, "What love tells me",

portrays deep human feeling

as the ultimate

reality, transcending the

apparently simplc sentiment

of the movements main melody

by generating

an apotheosis of epic

grandeur. The Adagio’s

variation-like structure and

superbly controlled culminative

effect underline the sense

of a progression within a

sustained state of mind, as

if to argue that love

consoles us by encouraging

us to live intensely in the

present, occasional doubts

and crises serving only to

reinforce and ultimately

ennoble that consolation.

Alternatively, the music’s

chorale-like recurrences can

be heard as a prayerful

ascent to a vision of the

Divine, in which humanity at

last conquers nature and

attains immortality. Either

reading is possible: yet the

sheer assertive power of the

ending, as if Mahler

wants to evoke the ambiguity

attending the gods’ entry

into Valhalla at the end of

Wagner’s Das Rheingold,

seems to say that the spirit

which triumphs here is,

above all, mortal. Mahler’s

message is that all songs in

human music are of the

earth, and all human

symphonies, even the

grandest, are artefacts,

whose possible wider

significances remain matters

of endless, fascinating, but

necessarily inconclusive

debate.

Arnold

Whittall

|

|

|