|

|

DG - 2

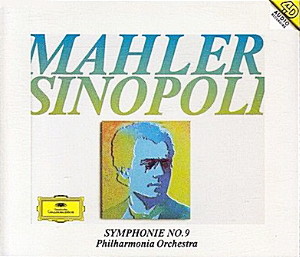

CDs - 445 817-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 9 |

|

82' 39" |

|

Compact Disc 1

|

|

43'

25" |

|

| -

1. Andante comodo |

28' 09" |

|

|

| -

2. Im Tempo eines

gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas

täppisch und sehr derb |

15' 15" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

39'

14" |

|

| -

3. Rondo-Burleske. Allegro

assai. Sehr trotzig |

13' 16" |

|

|

| -

4. Adagio. Sehr langsam und

noch zurückhaltend |

25' 54" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All

Saints' Church, Tooting, London

(Gran Bretagna) - dicembre 1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Hans-Rudolf

Müller |

|

|

Editing |

|

Mark

Buecker |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 445 817-2 | LC 0173 | 2

CDs - 43' 25" & 39' 14" | (p)

1995 | 4D DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although the

Ninth was the last of

Mahler’s symphonies to be

completed in fully

orchestrated fair

copy, the period of its

composition overlapped with

that of Das Lied von der

Erde, which preceded

it, and the sketched but

unfinished Tenth Symphony.

Following the exhumation and

reconstruction

of the latter, the three

works have come to be

regarded almost as a

trilogy, for understandable

reasons. All are elegiac;

all are marked by emotional

pain and the ill-health to

which Mahler’s busy winter

conducting-schedule in

America contributed. Behind

the events and

preoccupations of his later

years lay a fateful chain of

events that had begun in

1907. Mahler had resigned

his directorship of the

Vienna Court Opera; his

eldest daughter had died; he

had been diagnosed as

suffering from a

heart-condition. Their house

on the Wörthersee

had been sold and from 1908

he and his wife, Alma, with

their remaining daughter,

spent their summers in

Toblach, in the Tyrol. It

was mostly there that the

last three works were

composed. It was also there

that Mahler confronted the

fact not only of his own

mortality, but also of his

much younger wife’s

increasing estrangement from

him. Whatever meaning he

attributed to the Ninth

Symphony, it is perhaps

significant that he appears

to have regarded it as a

peculiarly private work.

While he played the whole of

Das Lied von der Erde

to Alma and had

shown the score to Bruno

Walter, neither of them saw

very much of the Ninth. He

alluded to its composition

in letters to Walter, but

only once did he say

anything very specific about

it. What he said was

cryptic:

You did

guess the real reason for

my silence. I have been

working very hard and am

just putting the finishing

touches to a new symphony

... In it something is

said that I have had on

the tip of my tongue for

some time - perhaps (as a

whole) to be ranked beside

the Fourth, if anything

(but quite different). As

a result of working in mad

haste and agitation the

score is rather a scrawl

and probably quite

illegible to anyone but

myself. And so I dearly

hope it will be granted to

me to make a fair copy

this winter.

Dark and

distressing though the

personal circumstances

surrounding its composition

may have been, the Ninth is

as rich and complex in

emotional range as any

Mahler symphony. Even in the

slow movements with which it

begins and ends, lamentation

and the mood of leave-taking

are defined by the energetic

aspiration and anger that

they constantly inspire. We

may hear the symphony as a

subjective confrontation

with despair, but that

confrontation, as always

with Mahler, is presented as

a creative project: a series

of problems about how and

why a symphony might unfold

when the very point of the

genre, whose roots lay in 19th-century

optimism and romantic

heroics, seemed called into

question by knowledge that

was as much cultural and

historical

as subjectively personal. It

is for this reason that the

Ninth Symphony, like

Mahler’s other late works, seems to

mark the end of a

tradition in a way that

is, however,

extraordinarily modern in

its self-awareness and

expressive immediacy.

*****

The German

philosopher Theodor Adorno

once movingly suggested

that “Mahler’s music

passes a maternal hand

over the hair of those to

whom it turns.” Certainly

the opening theme of the

Ninth’s first movement,

emerging in D major

against a background of

fragmentary rhythmic and

motivic elements, is

profoundly consoling,

almost a lullaby. Its

recurring statements,

always in D major, are

nevertheless increasingly

burdened by knowledge of

what and

why they need to console.

The melody seems to grow

older, wiser, perhaps

sadder as the movement

progresses, propelled by

the angry momentum of the

dissonantly aspiring

second theme. Its climax

is marked by a powerful

fanfare-like motif. It

aims for the heights of

Mahler’s earlier and more

visionary symphonies only

to hurl us back down to

earth where the D major

theme resumes its now more

agonized task of

consolation. The movement

progresses in recurring

cycles of these three

elements, sometimes still

more sharply contrasted,

sometimes identified and

almost conflated with each

other. Their discourse is

intruded upon by darkly

insistent statements of

the opening rhythmic

figure which takes on the

character of a “Fate”

motif. “Like a ponderous

funeral-cortüge”

reads one of the score’s

later annotations.

Mahler’s manuscript had

included others. Over one

of the most delicate

restatements of the D

major theme, on solo

violin, he had written “O

youth! Disappeared! O

love! Blown away!”

As the music fades into

silence at the end, he had

added (again over the solo

violin) “Farewell! Farewell!"

The two central movements

explore more physically

energetic ways of dealing

with troublesome

consciousness.

The second movement is a

long scherzo that

typically (for Mahler)

encompasses the three main

dance forms of its

Austrian heritage: Minuet,

Ländler

and Waltz. In

the manuscript, however,

its title was “Menuetto

infinito”, suggesting a

dance whose component

parts return in unending

succession, each

dispelling the reveries of

recollection and

self-quotation into which

the previous episode may

have fallen. The third

movement is really a

bitterly ironic finale,

placed deliberately in the

wrong place. This Rondo is

a “burlesque” in which the

energetic fury of the

second movement of

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony

sets off a firework

display of

contrapuntal

ingenuity. Its cumulative

effect, however, is of a

kind of “anti-music”: a

whirl of ceaseless and

ultimately senseless

activity from which escape

seems to be promised only

by the long central

episode. Heavenward

ascent, however, is met

with scornful woodwind

statements of what will

become the

opening motif of the

closing Adagio. Escape

thwarted, the Rondo

material returns with

renewed vehemence. Its

deafening crudity puts

paid to beatific visions.

As a result, the final

Adagio is from the outset

burdened by tragic

awareness. The temperature

of its chorale-like theme

is raised by “espressivo”

partwriting that

constantly threatens to

destroy the music from

within. Overlapping vocal

"turns",

urgent chromatic

inflections and eloquent

harmonic sidestepping into

unexpected regions

characterize a music that

musters its strength

against all odds. A quite other

world is explored by the

subsidiary idea: high

violins set against a deep

bass-line and marked

"without feeling".

This music of otherworldly

strangeness opens

mysterious spaces between

successive variants of the

ever more urgently engaged

adagio theme.

At the end the exprcssive

consciousness of the music

itself seems gradually to

slip into that realm of

otherness. On the last

page of the score, the

first violin line quotes

from the fourth of

Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder:

"It

will be a fine day on

those heights". The

previous line in the song

had insisted: “We will

catch up with them”. At

the end there is no

consolation, however;

neither are we crushed

with the melodramatic

negation of the Sixth

Symphony. The music, like

the subjective awareness it

had symbolized, simply

dies away into silence.

Mahler

never heard the Ninth

Symphony in performance.

It received its posthumous

première

in Vienna,

conducted by Bruno Walter,

on 26 June 1912.

Peter

Franklin

|

|

|