|

|

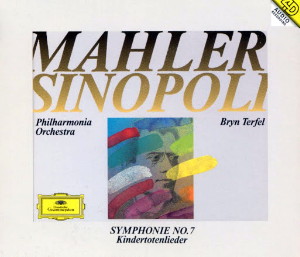

DG - 2

CDs - 437 851-2 - (p) 1994

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1

|

|

51'

34" |

|

| Symphonie Nr. 7 |

|

87' 26" |

|

| -

1. Langsam (Adagio) - Allegro

risoluto, ma non troppo |

24' 36" |

|

|

| -

2. Nachtmusik. Allegro moderato |

17' 04" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo. Schattenhaft |

9' 54" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

62'

27" |

|

| -

4. Nachtmusik. Andante amoroso |

17' 35" |

|

|

| -

5. Rondo-Finale. Tempo I (Allegro

ordinario) - Tempo II (Allegro

moderato ma energico) |

18' 17" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kindertotenlieder

|

|

26' 22" |

|

nach

Gedichten von Friedrich Rückert

|

|

|

|

| -

1. Nun will die Sonn' so hell

aufgehn (Langsam und schwermütig;

nicht schleppend) |

6' 22" |

|

|

| -

2. Nun seh' ich wohl, warum so

dunkle Flammen (Ruhig, nicht

schleppend) |

5' 10" |

|

|

| -

3. Wenn dein Mütterlein (Schwer,

dumpf) |

5' 01" |

|

|

| -

4. Oft denk' ich, sie sind nur

ausgegangen (Ruhig bewegt, ohne

zu eilen) |

3' 16" |

|

|

| -

5. In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus

(Mit ruhelos schmerzvollem

Ausdruck) |

6' 33" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bryn TERFEL, Bariton |

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All

Saints' Church, Tooting, London

(Gran Bretagna):

- maggio 1992 (Symphonie No. 7)

- novembre 1992

(Kindertotenlieder) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Co-production |

|

Pål

Christian Moe (Kindertotelnlieder) |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Hans-Rudolf

Müller (Symphonie No. 7), Stephan

Flock (Kindertotenlieder) |

|

|

Editing |

|

Hans

Kipfer (Symphonie No. 7), Oliver

Rogalla (Kindertotenlieder) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 437 851-2 | LC 0173 | 2

CDs - 51' 34" & 62' 27" | (p)

1994 | 4D DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie

Nr. 7

A music historian

with a taste for melodrama

might be tempted to describe

Mahler’s Seventh Symphony as

the musical composition

which embodies the precise

moment of Romanticism’s

collapse - a collapse which

took traditional symphonic

form and tonality down with

it, as Mahler’s

Viennese friend Arnold

Schoenberg was the first to

recognize. A more temperate

historian might point out

that, while Mahler’s

Seventh is undoubtedly in

the category of the

problematic, its special

qualities make sense if the

work is seen as the

composer’s answer to his

uncompromisingly “final”

Sixth Symphony. As, in

effect, a new start, it also

had inestimable value in

helping Mahler to prepare

for the achievements of the

last two completed

symphonies and Das Lied

von der Erde -

works which gave early

notice that (despite

Schoenberg and his

disciples) the 20th century

would remain deeply divided

on the issue of whether or

not Romanticism, tonality

and traditional symphonic

form had collapsed at all.

Now that the Seventh

Symphony is regularly

performed and recorded as a

valued part of the Mahler

canon it is less necessary

to find excuses for it, but

still useful to consider its

special qualities.

Particularly special is its

tendency to exaggerate - to

test to breaking point -

many of the most personal

aspects of style and

structure found in Mahler’s

earlier symphonies.

Melodramatic music history

may raise its head again in

the suggestion that the

Seventh seems to be the work

of a composer profoundly

aware of the instability of

all that he held dear, not

least in his personal life,

and in the further

suggestion that this

awareness motivated this

defiant outpouring of a

creative personality unable

to identify with the new

Schoenbergian radicalism,

yet also unable to defend

the old Romanticism with any

great conviction. After all,

even if the commonsense view

prevails that the work, and

especially the Finale, is

simply less good than most

of its fellows in the Mahler

canon, the question remains:

why? The Seventh seems to be

the work in which Mahler

most pressingly felt the

need to combine attack and

defence, the work that calls

conventional symphonic

criteria into question while

at the same time seeking to

reassert their continuing

validity. It is, in other

words, something of an

experiment after the deeply

personal drama of the Sixth,

and it is therefore hardly

surprising if the result is

less polished and less

coherent than Mahler at his

best.

The source of the Seventh

Symphony lies in the fertile

summer of 1904, when Mahler’s

compositional activity

during his holiday break

from the trials and

tribulations of operatic

politics in Vienna included

the completion of the Sixth

Symphony and the Kindertotenlieder.

With the overwhelmingly

tragic end of the Sixth

fresh in his mind, as well

as the serene but sorrowful

resignation that concludes

the songs, it is

understandable that he

should have begun to think

of his next project as

closer in spirit to the

Symphony no. 5: progressing,

in essence, from despair to

joy, tragedy to triumph.

Even so, the only

contributions to this scheme

composed during the summer

of 1904 were the Seventh’s

eventual second and fourth

movements, both called Nachtmusik,

and both at some remove from

the main, more substantial

structures which the work

would need. Not until the

summer of 1905

was Mahler able to get down

to the symphony’s principal

movements, and there were

difficulties, especially

with the first, which seems

to have been, in drafting

terms, the last to fall into

place. It may therefore be

that it was this process of

composing the symphony

“inside out”, as it were,

that provoked Mahler into

questioning the continuing

validity of the kind of

inevitable progressions to

serenity, triumph or tragedy

on which his earlier works

had depended. The triumph

that ends the Fifth Symphony

preserves an unambiguously

heroic tone, due mainly to

the strong lyric profile of

the movement’s main

material. By contrast, the

Finale of the Seventh, by

appearing to aspire to a

spirit of ebullient comedy,

reveals a much more

equivocal response to the

heroics articulated in the

first movement. The Finale

seems, to use a favourite

late-20th-century

word, more a deconstruction

of the work’s heroic spirit

than its fulfilment.

These essential conflicts

and diversities of mood are

reflected in the Seventh

Symphony’s basic materials.

The main thematic ideas

derive from those Mahlerian

melodic archetypes that

appear in all his works like

an obsessively repeated

signature. But these

familiar landmarks are

offset by disorientating

shifts of tonality and by

radical contrasts of

orchestral colouring. For

example, to speak of an

overall progression from the

B minor of the first

movement’s slow introduction

to the C major of the Finale

- even though that C

tonality is present in part

of the first movement and

dominates the second - is to

imply a consistently

evolving, Romantic journey

of the kind that is

perfectly appropriate for

the Fifth Symphony as it

travels from its C sharp

minor Funeral March to its

life-affirming D major

Finale. In the Seventh,

however, the Finale’s

overall C tonality is not so

much an affirmative answer

to the first movement’s

stressful E tonality as an

assertion of difference, a

dismissal as much as a

resolution. It is in this

sense that the work most

powerfully questions what it

also attempts to preserve -

the fundamentals of

Mahlerian symphonic coherence.

When it comes to

matters of style, the first

movement has the

epic-Romantic qualities

familiar from earlier Mahler

- the Sixth Symphony, in

particular. The plangent

tenor horn theme that

launches the slow

introduction over a muffled,

throbbing accompaniment

inevitably evokes that

favourite Mahlerian genre of

the funeral march, and

although this is then

transformed into the

ultimately jubilant fast

march of the main Allegro,

carried forward on a

compelling tide of

aspiration and excitement, a

strongly idealistic spirit

remains in evidence, most

obviously in the rapt

chorale-like theme which

recalls the self-sacrificing

Senta’s music in Wagner’s Flying

Dutchman. In

the first Nachtmusik

movement the mood shifts

from heroic to pastoral, but

the march-character is

maintained, in a brilliantly

conceived confrontation

between folklike material

and a sinister military

gait, where it becomes

impossible to disentangle

birdsong from bugle calls.

The Scherzo is cast as a

fast ländler,

marked Schattenhaft

(“shadowy”), a

quintessentially Mahlerian

dance in which the macabre

is never far from the

surface, and attempts to

establish a more relaxed

atmosphere simply provoke

resistance and greater

anxiety: this is summed up

at the end, where the abrupt

dismissal of minor-key

harmony by a major chord,

despite its apparent

finality, leaves an air of

instability. After this, the

wistful romancing of the

Andante amoroso, which makes

a special feature of the

courtly timbres of guitar,

mandolin and harp, goes as

far as Mahler can to purging

the anxieties of what has

gone before - an effect all

the more striking when one

remembers that this movement

was written before either

the Scherzo or the first

movement. In view of what is

to come, the Andante amoroso

might seem unreal in its

romantic intimacy; while

there is nothing false about

its fleeting tenderness and

beauty, the gentle moonlight

is submerged in shadow from

time to time, and even the

more expansive, genial

episode that provides the

movement’s main contrast

makes no lasting impact.

The Rondo-Finale then subverts

the spirit of all that

precedes it in an

exuberantly unholy

confrontation between

militarism and religion,

march and chorale.

Whereas earlier Mahler

finales bring the turbulent

and pastoral facets of

Romantic feeling into a

serene, an affirmative or a

tragic synthesis, this one

seems determined to exclude

Romance in favour of a

starker style in which

comedy, a Falstaffian

bluster and bravado, is

king. There may be an ironic

post-Wagnerian

subtext in the way the

symphony's

nightmusic yields in the

Finale to a day-music

fraught with nightmarish

instability, although the

Finale sounds in places more

like Die Meistersinger

than those passages in Tristan

und Isolde where the

horrors of day and light are

described. Be that as it

may, there is a sense in

which Mahler’s

characteristically

transcendent chorale music

(which would be restored to

its proper affirmative role

in the Eighth Symphony) is

transformed here into a

defiantly secular hedonism,

with an insistence that has

as much of hysteria as of

joy about it. As a Rondo

whose contrasts seem to be

inserted for maximum

dislocatory effect, the

movement can even be

understood as a parody of a

Nietzschean, Dionysiac

dithyramb, wild in spirit

yet curiously simple in

musical language.

Arnold

Whittall

Kindertotenlieder

The Seventh’s Finale

can be seen as a complex

attempt on Mahler’s part to

express his deeply

ambivalent feelings about

life in general and

symphonic form in

particular: or it can be

seen, more simply, as a

failed attempt to match the

Fifth Symphony’s extended

happy ending. Either way it

reinforces the conviction

that Mahler’s expressive

world was a rich amalgam of

opposed elements - innocence

and bitterness, joy and

despair, and in no work of

his are these oppositions

more starkly presented than

in the Kindertotenlieder.

Critical response to

Mahler’s decision to set

these touchingly fragile

poems by Friedrich Rückert

is inevitably coloured by

the knowledge that, three

years after their completion

in 1904, Mahler’s daughter

Maria died, not yet five,

from scarlet fever. For life

to imitate art in this way

is distressing enough, but

it is at least possible for

those who appreciate art to

argue convincingly that the

extreme and unmediated

emotions of real life are

transcended

here in small-scale

structures which, by way of

subtle harmonic inflections

and telling formal

refinements, avoid the

maudlin and the lachrymose.

Kindertotenlieder

is in the tradition of the

19th-century cycle or set of

songs (normally with piano

accompaniment) which, while

not offering a specific

narrative, are linked by

common subject-matter.

Mahler underlines the

relatedness by casting the

first and last songs in the

same key, and also grouping

the three other songs around

similar tonalities. Tempos

are predominantly slow, but

variety of rhythmic

character prevents monotony,

and few other Romantic

compositions make such

effectivc use of that basic

contrast between the spare

bleakness of minor-key music

and the warmth, however

illusory, of major harmony.

In particular, the first and

final songs of the set

reflect a comparable

strategy in the first song

of Schubert’s Winterreise.

The progression in Mahler’s

final song from narrative

(the storm, the fear) to

resolution (reflections on

the peace of heaven) could

have offered only a macabre

aestheticization of a theme

that seems to defy artistic

treatment. Some listeners

may still resist what they

believe to be Mahler’s

sentimental endorsement of Rückert’s

saccharine

religiosity. For others,

however, the melodic poise

of the final stanza, and the

moment where words cease and

the melody passes from the

voice to the solo horn,

offer an experience that is

neither empty nor

exploitative. Just as in his

setting of Das

himmlische Leben at

the end of the Fourth

Symphony Mahler was able to

resolve that work’s diverse

elements into a convincing

vision of innocent

sublimity, so at the end of

Kindertotenlieder he

draws true serenity out of

extreme despair. Whether or

not this can quite dispel

the bitterness of the first

song’s minor key salute to

“the joyful light of day” is

one of those questions which

Mahler’s

music invites us to leave

unanswered.

Arnold

Whittall

|

|

|