|

|

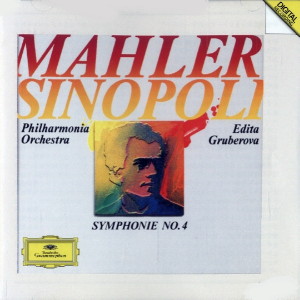

DG - 1

CD - 437 527-2 - (p) 1993

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 4 |

|

58' 03" |

|

| -

1. Bedächtig. Nicht eilen |

16' 17" |

|

|

| -

2. In gemächlicher Bewegung. Ohne

Hast |

10' 07" |

|

|

| -

3. Ruhevoll |

21' 52" |

|

|

| -

4. Sehr behaglich "Wir genießen

die himmlischen Freuden" (Text

aus "Des Knaben Wunderhorn) |

9' 47" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Edita GRUBEROVA,

Sopran |

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Watford

Town Hall, London (Gran Bretagna)

- febbraio 1991

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Editing |

|

Jörg

Ritter |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 437 527-2 | LC 0173 | 1

CD - 58' 03" | (p) 1993 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Soon after

completing his Fourth

Symphony, in the summer of

1900, Mahler told a

correspondent that “this one

is quite fundamentally

different from my other

symphonies”; yet he informed

another friend that the work

provided a “conclusion” to

its three predecessors. The

contradiction is more

apparent than real. Mahler’s

first four symphonies are

all involved with song in

various ways, and nos. 2, 3

and 4 contain settings of

texts from the early

19th-century collection of

folk poetry, Des Knaben

Wunderhorn. But it is

precisely because no. 4

continues and intensifies

the “song” aspect of its

predecessors that it differs

“fundamentally” from them.

The similarity of basic

approach stimulated a

crucial change of style.

The song “Das himmlische

Leben” - a child’s vision of

paradise - was already seven

years old when Mahler

conceived the Fourth

Symphony, so it would be

remarkable if it proved to

have had no influence on the

material and character of

the work - as indeed it had

already had on the Third

Symphony, in which Mahler

had originally planned to

include it. But the problem

Mahler now set himself was

quite specific. What kind of

symphony could effectively end

with such a relatively

slight movement? Late

Romantic finales had not

been notable for charm and

good humour. They were

crowning glories rather than

unassuming afterthoughts,

and all three of Mahler’s

earlier symphonies had ended

with heaven-storming

affirmations of tonal and

spiritual resolution. Any

rejection of such emphatic

culmination might therefore

be expected to promote

wholesale rethinking of the

entire symphonic scheme.

Though short in itself, “Das

himmlische Leben” did not in

the event provoke a

radically new concentration

in the Fourth Symphony as a

whole: the first three

movements are all

substantial structures. The

song’s light-hearted tone

undoubtedly generates the

style of the first movement,

which involves a very

Mahlerian kind of

neo-classicism - strongly

contrapuntal, referring

explicitly to the diatonic,

cadential formulae of Haydn

and his contemporaries.

Nevertheless, the symphony’s

strength of character stems

from the need not to exclude

moments of drama and high

emotion, but to give them a

new context: to subordinate

them in ways which would

allow “Das himmlische Leben”

to emerge as a logical

outcome, a distillation, of

the preceding symphonic

process.

The first movement

establishes this new manner

to perfection in the playful

formality of its principal

ideas and the sharply etched

nature of its orchestration,

with woodwind and trumpets

particularly prominent.

Mahler seems determined to

keep tension at a low level

in the exposition, which

ends with greater finality

than classical orthodoxy

would ever have allowed. In

the development, however,

geniality reveals a darker

side, and a masterful series

of modulations engineer a

climax of great emotional

power. In the reprise the

warmly lyrical contrasting

theme is almost parodied: it

is as if Mahler wants the

listener to question how

seriously he is taking his

material, in order to

enhance the spontaneity of

the movement's

final stages. Here courtly

good humour and delight in

technical expertise evoke

the finale’s image of

first-class professional

musicians - “treffliche

Hofmusikanten”.

The second movement has the

easy rhythmic flow of a Ländler

or a minuet, but its sinuous

themes and shifting

harmonies quickly turn

sinister, spectral, with the

quality of a danse

macabre. At one stage

Mahler called the movement

“Death takes the fiddle",

and the prominent solo

violin enhances the ghostly

atmosphere. The more relaxed

mood of the contrasting

sections can never fully

establish itself in this

environment, and the

movement ends with the

abruptness of a sudden

awakening from a disturbing

dream.

The slow movement counters

this, initially, with music

of expansive serenity. But a

tonal switch from major to

minor is all it takes to

create an emotional crisis,

and the movement evolves

through alternalions. Two

increasingly hectic

variations of the main theme

frame a turbulent rethinking

of the minor key episode.

But after the second

variation, when stability

and serenity are restored,

it seems that the movement

is destined to subside into

a rapt, reticent coda. So it

does, but not before a

sudden explosion of

triumphant fanfares

prefigures the finale’s

vision of paradise. Even so,

the question remains: how

can the setting of such a

slight, light-hearted text

ensure a fitting end to a

work of such wide emotional

range and textural

sophistication?

Mahler answers the question

by creating the impression

that the finale’s spirit, as

well as its actual material,

is distilled from what has

preceded it. Motivic

associations with the

exuberant first movement are

clear, and there is also a

basic shift of tonality,

from G major to E major,

which ties in with the slow

movement’s most dramatic

moment. The scherzo’s

sinister dance is here

transmuted into the angels’

carefree skipping. Mahler

also confronts the poem’s

challenge head on. “There’s

no music on earth / that can

be compared [with that of

heaven]”, the poem

proclaims. But the touching

simplicity of Mahler’s

ending, encapsulated in the

singer’s final descending

scale, offers a gentle

corrective. The whole work

has been designed to express

and explore a special

musical innocence and joy

without lapsing into

primitivism or monotony.

Symphony resolves into song,

and dramatic tension

dissolves into the gentle

flow of the final

procession, a transfigured

march receding into infinity

on the last note of the

double basses: the music of

paradise regained.

Arnold

Whittall

|

|

|