|

|

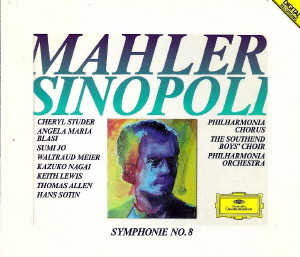

DG - 2

CDs - 435 433-2 - (p) 1992

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 8 |

|

64' 54" |

|

Compact Disc 1

|

|

25'

09" |

|

ERSTER

TEIL

|

|

|

|

| Hymnus:

"Veni, creator spiritus" |

|

25' 09" |

|

-

1. Allegro impetuoso "Veni, creator

spiritus"

|

1' 22" |

|

|

| -

2. A tempo. Etwas (aber

unmerklich) gemäßigter; immer sehr

fließend "Imple superna

gratia" |

3' 58" |

|

|

| -

3. Tempo I. (Allegro impetuoso)

"Informa nostri corporis" |

2' 42" |

|

|

| -

4. Tempo I. (Allegro, etwas

hastig) |

1' 29" |

|

|

| -

5. Sehr fließend - Noch einmal so

langsam als vorher. Nicht schleppend

"Informa nostri corporis" |

3' 17" |

|

|

| -

6. Plötzlich sehr breit und

leidenschaftlichen Ausdrucks - Mit

plötylichem Aufschwung "Accende

lemen sensibus" |

4' 57" |

|

|

| -

7. "Veni, creator spiritus" |

3' 52" |

|

|

| -

8. a tempo "Glori sit Patri Domino" |

3' 30" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

58'

04" |

|

| ZWEITER

TEIL |

|

|

|

| Schlußszene

aus Goethes "Faust II" |

|

58' 04" |

|

| -

1. Poco adagio |

5' 49" |

|

|

| -

2. Più mosso. (Allegro moderato) |

3' 34" |

|

|

| -

3. Wieder langsam - Chor und Echo:

"Waldung, sie schwankt heran" |

4' 07" |

|

|

| -

4. Moderato - Pater ecstatisuc:

"Ewiger Wonnebrand" |

1' 28" |

|

|

| -

5. Allegro. (Allegro

appassionato) - Pater

profundus: "Wie Felsenabgrund mir zu

Füßen" |

4' 50"

|

|

|

-

6. Allegro deciso. (Im Anfang

noch nicht eilen) - Chor der

Engel: "Gerettet ist das edle Gleid

der Geisterwelt vom Bösen"...

|

0' 53"

|

|

|

| -

7. Molto leggiero - Chor der

jüngeren Engel: "Jene Rosen aus den

Händen" |

1' 43"

|

|

|

| -

8. Schon etwas langsamer und immer

noch mäßiger - Die vollendeteren

Engel: "Uns bleibt ein Erdenrest" |

2' 24"

|

|

|

| -

9. Im Anfang (die ersten ier

Takte) noch etwas gehalten -

Die jüngeren Engel: "Ich spür'

soeben, nebelnd um Felsenhöh'"... |

1' 10"

|

|

|

| -

10. Sempre l'istesso tempo - Doctor

Marianus: "Höchste Herrscherin der

Welt" |

5' 07" |

|

|

| -

11. Äußerst langsam. Adagissimo -

Chorus I/II: "Dir, der

Unberührbaren"... |

3' 29" |

|

|

| -

12. Fließend - Magna Peccatrix: "Bei

der Liebe, die den Füßen"... |

4' 21" |

|

|

| -

13. Una poenitentium: "Neige, neige,

du Ohnegleiche" |

0' 58" |

|

|

| -

14. Unmerklich frischer - Selige

Knaben: "Er überwächst uns schon" |

3' 46" |

|

|

| -

15. Una poenitentium: "Vom edlen

Geisterchor umgeben"... |

8' 03" |

|

|

| -

16. Sehr langsam beginnend - Chorus

mysticus: "Alles Vergängliche ist

nur ein Gleichnis" |

6' 21" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cheryl STUDER,

soprano/Sopran I (Magna Peccatrix)

|

PHILHARMONIA

CHORUS |

|

| Angela Maria

BLASI, sopran II (Una

poenitentium) |

THE SOUTHEND BOYS'

CHOIR |

|

| Sumi JO,

soprano (Mater gloriosa) |

Michael Crabb, Director |

|

| Waltraud MEIER,

contralto/Alt I (Mulier Samaritana) |

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Kazuko NAGAI,

contralto II (Maria Aegyptiaca) |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

| Keith LEWIS,

tenor (Doctor Marianus) |

Musical Assistant:

Guido Guida |

|

| Thomas ALLEN,

baritone (Pater ecstatisuc) |

|

|

| Hans SOTIN,

bass (Pater profundus) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All

Saints' Church, Tooting, London

(Gran Bretagna) -

novembre/dicembre 1990

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Co-production |

|

Pål

Christian Moe |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Editing |

|

Andrew

Wedman |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 435 433-2 | LC 0173 | 2

CDs - 25' 09" & 58' 04" | (p)

1992 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The première

in Munich of Mahler’s Eighth

Symphony on 12

September 1910

was one of the most

spectacular events of

musical Europe in the decade

preceding the First World

War.

This was a towering display

of cultural prestige at its

zenith

- the unveiling of one of

the most massive symphonies

ever conceived. Merely

to assemble and rehearse the

required forces would have

been astonishing (according

to the program, Mahler

performed it with 858

singers and 171

instrumentalists), but the

whole production was also

spatially coordinated to suit

the newly constructed, huge

Neue Musikfesthalle,

located in the Exhibition

grounds.

In short, the première

helped to celebrate and consecrate

a new temple for colossal,

Austro-Germanic art. Now in

precarious health and with

only eight months to live,

Mahler surely regarded this

occasion as the peak of his

public career.

The

symphony itself had been

drafted four years earlier,

in a mere ten weeks from

June to August 1906,

and the orchestration was

completed in 1907.

From the beginning Mahler

considered it the product of

a blaze of inspiration and

sudden insight. "I have

never written anything like

it,"

he announced to Richard

Specht in the summer of

1906. "It

is certainly

the largest thing that I

have ever produced." He

went

on to catalog the work’s

projected innovations

(including the uniting of

two movements whose texts

were drawn from different

languages and different

historical periods) and

claimed to be writing the first

symphony that was sung

throughout, "from beginning

to end."

In this respect it

contrasted with some of his

earlier symphonies, in

which, as in Beethoven`s

Ninth, the appearance of the

voice had been preceded by

several purely instrumental

movements.

The key to grasping the

Eighth Symphony lies in

confronting the daring of

its central conception. The

core idea from which it

springs is the attempt to

synthesize

strong contrasts or even

contradictory opposites - to

suggest the presence of a

larger unity that can

integrate the stylistic and

conceptual disunities that

are swirled together at

every level; voice vs.

orchestra; “dramatic

cantata” vs, “symphony”`;

densely textured, Bach-like

counterpoint vs.

“modern” sonata practice;

sacred vs. secular;

masculine vs. feminine;

the contradictory musical

styles from section to

section; and so on. Within

such a concept of total

inclusion - a central

postulate of Mahler`s

aesthetic - nothing may be

regarded as alien.

What from traditional

perspectives might scent

inconsistencies or

discontinuities are claimed

here to be transfornied into

virtues.

The central contrast

concerns the texts of the

symphony’s two movements,

which have sometimes been

criticized as fundamentally

irreconcilable. The first, sung

in Latin, is drawn from the

ninth-century hymn for

Pentecost (often attributed

to Hrabanus Maurus),

“Veni, creator spiritus”, a

celebration of the descent

of the Holy Spirit. The

second, sung

in German, comprises most of

the concluding scene from

the second part of Goethe’s

Faust (published in 1832).

This is the famous

“mystical” passage

recounting the denouement of

Faust’s sudden (and

unearned) salvation. It

features his purification

and ascension heavenward by

stages, at the end of which

he is permitted to glimpse,

in the presence of the Mater

Gloriosa (Blessed Virgin Mary),

the outlines of the truths

for which he has striven

throughout his life. In the

concluding eight lines,

uttered by the Chorus Mysticus

- a

central text for the

Germanic 19th century - we,

along with Faust, are

presented with the concepts

of the transience and

illusion of the material

world and with Goethe’s

conviction of the final

attainability of "the

indescribable" through the

process of masculine

striving toward the "eternal

feminine".

The larger point, though, is

that Mahler

seems to have taken the two

dissimilar texts as

representatives of two

contrasting ages of European

thought. Broadly construed,

we might consider them as

symbolizing the contrasting

paradigms of pre-Enlightenmcnt

and Enlightenment thought

(or pre-modern and modern

society). When Mahler

elected to juxtapose these

texts, he was doing nothing

less than addressing the

central rift in European

culture

of the preceding millennium,

the much-discussed tearing

away of the modern,

“progressive” age from the

unifying assurances of a

world that was once

perceived as whole. Moreover,

by suggesting that these

contradictory texts might be

brought into some sort of

unity - a unity to be

represented by allowing the

same thematic material to

underpin both movements - Mahler

was apparently claiming that

this seemingly inescapable

rift was capable of being

healed in the here and now.

From this perspective the

work may be considered to

harbor a strong utopian

element.

The conceptual world of the

Eighth Symphony presents us

with four principal agents

of healing. The first is

that of an overarching love,

conceived as broadly as

possible (both Caritas and

Eros, spiritual and physical

love, as Mahler had

suggested in a discarded,

early plan for the Eighth) -

an eternal love believed

capable of resolving the

world’s antagonisms. The

second, and related to it, is

the concept of unearned

grace and eventual

forgiveness, whether

symbolized by the descent of

the Holy Spiritat Pentecost

or by the panoply of

celestial forces encountered

by the ever-ascending Faust.

The third is the familiar

Romantic claim of the

redemptive power of music

(according to which

performing the symphony - or

subsequently contemplating

it - was capable of becoming

a healing act). And the

fourth is an unquestioning

faith in the power of the

individual genius, the

composer-conductor-stage

manager who was animating

the whole display and

commanding these diverse

forces into action. In this

sense the orchestral and

choral masses marshalled

onstage could be understood

as a visual and sonorous

symbol of a new, healed

community of the whole, one

that has finally transcended

division at all levels, and

one with which the audience

was to identify. It should

be added that this last

feature was also the

essential vision of the

finale of Beethoven’s Ninth

Symphony, although Mahler

extended it here to more

“cosmic” levels and

delivered it - in 1910 - at

a more urgent, far higher

pitch of musical and social

tension.

Thus from an even broader

vantage point the principal

musical symbol for such an

ambitious work as the Eighth

Symphony

might be “the event” itself,

embodied in the mounting of

an enormous apparatus for

which no expenses were to be

spared. Here we find a

culture of music celebrating

its own traditions and

claiming, as an essential

feature of that celebration,

to be able to bring together

the

deepest irreconcilables

of its social being. Above

all, we should notice the

similarity of the opening of

the symphony to its close

nearly an hour and a half

later. Both passages, which

share the same triumphant

“Veni, creator spiritus”

motive, embrace the wild

heterogeneity within as if

with a vast pair of arms - a

grand, musical St. Peter’s colonnade.

Mahler described the first

movement, the setting of the

“Veni, creator spiritus”

hymn, to Richard Specht as

written "strictly in the symphonic

form." By this he meant that

the musical structure, for

the most part, disregarded

the hymn’s poetic form - a

succession

of four-line

stanzas - and used instead

as a fundamental frame of

reference the standard,

three-part sonata form. In

fact, however, as was his

normal procedure, Mahler

treated the normative

structure in unusual ways,

and each of the three broad

sections (exposition,

development and

recapitulation) is best

considered a separate, free

region that may be altered

or expanded as needed to

accommodate the expressive

demands of the text.

The exposition sets the

first eight lines (two

complete stanzas). Launched

by a potent,

tonic E flat chord in the

full organ, the principal

theme serves as a

declamatory invocation,

"Veni, creator spiritus", a

musical idea that will

return, refrain-like, at various

points later in the

movement. The fluid

second theme, in an

unorthodox D flat, then A

flat major,

appears with the third

line`s appeal for divine

grace, "Imple

superna gratia", which

itself encloses a separate

appeal, “Qui Paraclitus

diceris,” as a center

section. After a sudden turn

back to the invocation ("Veni,

creator spiritus") and an

immediate broad cadence in

the E flat tonic,

bell-chimes signal the onset

of a new, contrasting

section, “Infirma

nostri corporis” (D minor, E

ffat

major) - this is perhaps

best considered as the

“transitional" opening of

the developmental space.

This development, which

includes a restatement of

the text “Infirma

nostri corporis”, is marked

by the sudden eruption of a

new theme shortly into its

course, one that will prove

to be perhaps the central

theme of the entire

composition This is the

celebrated “Aceende lumen

sensibus.” in E major,

fortissimo, a plea for the

divine light-spark to kindle

our

physical being toward life,

understanding, and love. Its

three-note upbeat followed

by a strenuous leap upward

will pervade most of the

second movement and will

ultimately find its

resting-point in that

movement’s final Chorus

Mysticus - the goal of the

entire symphony. Following a

hefty double-fugue ("Ductore

sic te praevio")

and ajubilant return of the

"Accende" idea, the

shortened recapitulation

brings back the "Veni,

creator spiritus" invocation

and several (but not all) of

the ideas of the exposition.

The medieval hymn’s

conclusion, "Gloria

sit Patri Domino", serves as

the text for the coda. This

both recalls the principal

ideas of the movement and,

at the end, forecasts in the

off-stage brass a central motive

of the movement to come (one

that joins the "Accende"

three-note upbeat

with the music later

associated with the

appearance of the Mater

Gloriosa, "Höchste

Herrscherin der Welt!").

The vast second movement is

radically unorthodox in

structure. Something ofa

mixture between a “formal”

choral cantata or oratorio

and a freeflowing Wagnerian

music drama, it seems

closely to

follow the sense of the

text. Here the listener must

imagine each new entering

voice or section as coming

from a higher level, as Faust`s

soul is first extracted away

from the flawed earth and

then borne buoyantly upward

into ever-purer, more

forgiving, and “truer”

regions. In

the largest structural

sense, the movement passes

through three broad zones.

Although Mahler

commentators have disagreed

about the precise

boundaries, all agree that

these correspond roughly to

slow movement, scherzo, and

apotheosis-finale, (One

should add that the thematic

interconnections between the

zones and the many strong

allusions to passages in the

first movement further

complicate the matter.)

Throughout the second

movement one may also trace

a gradual transformation

from dark orchestral colors

to light ones and from

sections that are controlled

largely by masculine voices

and principles to sections

emphasizing the feminine,

regarded - in characteristic

"Romantic" fashion - as a

complementary, redemptive

space existing outside of

the masculine proper.

The movement opens at its

lowest rung, Poco adagio (E

flat

minor), with an extended,

somber orchestral prelude.

This is the instrumental

vision of a bleak landscape

charged with mystical

potential - all is eerily

still, yet pervaded by

inner, expectant motion and

invisible tensions. Two

important themes are stated

at once: the solemn

pizzicato theme in the

cellos and basses, based on

the preceding movement’s "Accende

lumen sensibus";

and the closely related,

swaying theme overlaid in

the high woodwinds, a shaft

of light from above that

more clearly foreshadows the

movement`s final chorus,

“Alles Vergängliche.”

Eventually a chorus of

muttering Anchorites

completes the

rugged-landscape image, and

with the subsequent

entrances of the two Church

Fathers - stressing “earthly”,

physical experiences and

continuing the thematic

variants of the initial

melodic ideas - Faust`s soul

begins its journey upward

toward the light. Here the

music, by degrees, begins to

accelerate in tempo, pushing

toward the scherzo-zone to

come.

The gateway into the scherzo

is the Allegro deciso, B

major women’s chorus.

“Gerettet ist das edle

Glied,” which clearly echoes

the first movement`s

“Accende lumen sensibus.”

The scherzo proper, however,

is probably best considered

to begin with the Younger

Angels` E flat

Rose Chorus, "Jene Rosen aus

den Händen,"

actually marked scherzando

in the score, In the

Angel-Scherzo Faust’s soul

is proclaimed as saved, and

he is borne further aloft:

the orchestration, too,

becomes markedly lighter.

Particularly to be noted

here is the pointed return

of several additional ideas

from the first movement.

These returns occur

throughout the scherzo, but

they become particularly

evident with the passage

leading up

to and including the

entrance of the More Perfect

Angels (“Uns bleibt ein

Erdenrest”), which is taken

directly from the

"transitional" opening of

the first movement`s

development ("Infirma

nostri corporis")

and leads to explicit

statements of various forms

of the "Veni, creator

spiritus"

motive. Here in the scherzo

the grand task of the entire

work, the harmonizing of the

two "irreconcilable" texts,

is first envisioned as a

clear possibility. This

concern will be pursued even

more vigorously in the final

section.

The concluding zone,

the apotheosis-finale that

gathers up and binds

together the symphony`s

leading musical ideas, is

often

considered to have begun as

the Greek-chorus-like Dr.

Marianus directs our

attention upward to the

Blessed Virgin, or Mater

Gloriosa, herself ("Höchste

Herrscherin

der Welt!",

E maior,

another of the central

themes toward which the

entire work has been

growing).

At this point Goethe’s

concept of the

feminine-as-goal is

crystallized into clear

images: three women

reverently celebrated by the

Church - and finally

Gretchen herself, the

innocent victim of the first

part of Faust -

begin to intercede on the

protagonist`s behalf. (As if

to underscore the

unworldliness of the

experience, the

orchestration becomes

progressively more

transparent, exotic and

extreme.) After having

visited several contrasting

tonal areas, the tonic E flat

major returns to ground (or

"resolve")

the entire symphony at the

moment when the Mater

Gloriosa grants Gretchen the

task of tutoring Faust in

the higher things ("Komm!

hebe

dich zu höhern

Sphären"), and

it continues this grounding

function throughout the

Marianus-led "Blicket

auf" chorus.

Toward the end a reverent

hush settles on the music to

introduce what is proposed

as the final revelation, available

only at the end of life’s

struggles - Goethe’s famous

concluding lines, "Alles

Vergängliche

/ Ist nur ein Gleichnis",

sung by the Chorus Mysticus

and led further upward by,

especially, a pair of solo

sopranos. All of this builds

to an ecstatic, affirmative

peak and merges at the end

with ringing orchestral

statements of the symphony’s

opening invocation, “Veni.

creator spiritus.”

James

Hepokoski

|

|

|