|

|

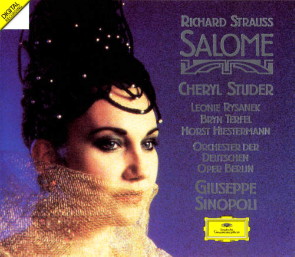

DG - 2

CDs - 431 810-2 - (p) 1991

|

|

| Richard

STRAUSS (1864-1949) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Salome |

|

101' 46" |

|

| Musikdrama in

einem Aufzug nach Oscar Wildes

gleichnamiger Dichtung (Deutsch

von Hedwig Lachmann) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compact Disc 1 |

|

56'

28" |

|

ERSTE

SZENE

|

1.

"Wie schön ist die Prinzessin salome

heute nacht!" |

2' 43" |

|

|

|

2.

"Nach mir wird Einer Kommen" |

2' 28"

|

|

|

ZWEITE

SZENE

|

3. "Ich will nicht

bleiben. Ich kann nicht bleiben" |

1' 42" |

|

|

|

4.

"Siehe, der Herr ist gekommen" |

1' 36"

|

|

|

|

5.

"Jauchze nicht, du Land Palästina" |

4' 13" |

|

|

|

6.

"Laßt den Propheten herauskommen" |

2' 19"

|

|

|

| DRITTE SZENE

|

7.

"Wo ist er, dessen Sündenbecher

jetzt voll ist?" |

4' 34" |

|

|

|

8.

"Er ist schrecklich. Er ist wirklich

schrecklich!" |

2' 02" |

|

|

|

9.

"Wer ist dies, Weib, das mich

ansieht?" |

2' 33" |

|

|

|

10.

"Jochanaan! Ich bin verliebt in

deinen Leib!" |

2' 18" |

|

|

|

11.

"Dein Leib ist grauenvoll" |

2' 27" |

|

|

|

12.

"Zurück, Tochter Sodoms! Berühre

mich nicht!" |

2' 44" |

|

|

|

13.

"Niemals. Tochter Babylons, Tochter

Sodoms, ... Niemals!" |

1' 12" |

|

|

|

14.

"Word dir nicht bange, Tochter der

Herodias?" |

2' 57" |

|

|

|

15.

"Laß mich deinen Mund küssen,

Jochanaan" |

1' 00" |

|

|

|

16.

"Du bist verflucht" |

5' 08" |

|

|

| VIERTE SZENE

|

17.

"Wo ist Salome? Wo ist die

Prinzessin?" |

3' 28" |

|

|

|

18.

"Salome, komm, trink Wein mit mir" |

2' 44" |

|

|

|

19.

"Sieh, die Zeit ist gekommen" |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

20.

"Wahrhaftig, Herr, es wäre besser,

ihn in unsre Hände zu geben" |

0' 53" |

|

|

|

21.

"Siehe, der Tag ist nahe, der Tag

des Herrn" |

2' 36" |

|

|

|

22.

"O über dieses geile Weib, die

Tochter Babylons" |

2' 27" |

|

|

|

Compact Disc 2 |

|

45'

18" |

|

|

1.

"Tanz für mich, Salome" |

4' 04" |

|

|

|

2.

"Salomes Tanz der sieben Schleier" |

9' 28" |

|

|

|

3.

"Ah! Herrlich! Wundervoll,

wundervoll!" |

4' 20" |

|

|

|

4.

"Salome, ich beschwöre dich" |

3' 14" |

|

|

|

5.

"Salome, bedenk, was du tun willst" |

2' 49" |

|

|

|

6.

"Gib mir den Kopf des Jochanaan!" |

1' 50" |

|

|

|

7.

"Es ist kein Laut zu vernehmen" |

2' 21" |

|

|

|

8.

"Ah! Du wolltest mich nicht deinen

Mund küssen lassen, Jochanaan" |

11' 19" |

|

|

|

9.

"Sie ist ein Ungeheur, deine

Tochter" |

1' 18" |

|

|

|

10.

"Ah! Ich habe deinen Mund geküßt,

Jochanaan" |

4' 36" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Horst HIESTERMANN,

HERODES, Tetrarch von Judäa |

ORCHESTER DER

DEUTSCHEN OPER BERLIN |

|

| Leonie RYSANEK,

HERODIAS, Gemahlin des Tetrarchen |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

| Cheryl STUDER, SALOME,

Tochter der Herodias |

Musical assistance:

Patrick Walliser |

|

| Bryn TERFEL, JOCHANAAN,

der Prophet (Johannes der Täufer) |

|

|

| Clemens BIEBER,

NARRABOTH, der junge Syrier, Hauptmann

der Wache |

|

|

| Marianne RØRHOLM,

DER PAGE DER HERODIAS |

|

|

| Uwe PEPER, ERSTER

JUDE |

|

|

| Karl-Ernst MERCKER,

ZWEITER JUDE |

|

|

| Peter MAUS, DRITTER

JUDE |

|

|

| Warren MOK, VIERTER

JUDE |

|

|

| Manfred RÖHRL, FÜNFTER

JUDE |

|

|

| Friedrich MOLSBERGER,

ERSTER NAZARENER |

|

|

| Ralf LUKAS, UWEITER

NAZARENER |

|

|

| William MURRAY,

ERSTER SOLDAT |

|

|

| Bengt RUNDGREN,

ZWEITER SOLDAT |

|

|

| Klaus LANG, EIN

KAPPADOZIER |

|

|

| Aimée WILLIS, EIN

SKLAVE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Jesus-Christus-Kirche,

Berlin (Germania) - dicembre 1990 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio

|

|

|

Produced by |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Co-Producer |

|

Pål

Christian Moe |

|

|

Balance

Engineer |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Publishers |

|

Fürstner

GmbH, Mainz, vertreten durch den

Verlag B. Schott's Söhne, Mainz |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 431 810-2 | LC 0173

| 2 CDs - 56' 28" & 45' 18"

| (p) 1991 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strauss, Wilde

and "Salome"

Neither the

literary nor the musical worldhas quite known what

to make of the Salome of

Oscar Wilde and Richard Strauss. Although he

considered it “a specious second-hand work”, Mario

Praz accurately caught the ambivalence of

Wilde’s play in noting that the “childish prattle

employed by the characters” seems, perhaps

unintentionally, to reduce decadence to parody or

“the level of a nursery tale”. That Wilde’s Salomé

may be the forerunner, according to

Richard Ellmann, of the plays of Beckett and

Yeats presents a problem for critics, since

the historical importance and technical virtuosity

of both play and opera have never seemed adequate

to overcome the supposed depravity in

Wilde and the alleged banality of Strauss’s

musical material. The situation has merely been

rendered more confused by the discrepancy between

the opera’s immediate popularity with

audiences from its first performance in Dresden on 9

December 1905 and the warnings of moral

corruption which issued from authorities after the

Lord Chamberlain banned the play in 1892, the

year of its completion. The cast which opposed

play and opera in two continents had an element

of the comical; any group which united English

censorship, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Archbishop

Piffl of Vienna and J. P. Morgan in moral

outrage already contained within itself the

seeds of ridicule; the

difficulties which Strauss

experienced in having the work staged in Vienna or

New York were ultimately minor obstacles to

its triumphant progress. But the more considered

charges aimed against Wilde and Strauss by

serious critics, analysts and aestheticians

have fully balanced the often lavish praise

bestowed upon the opera by Strauss’s fellow

professionals such as Schoenberg, Mahler,

Busoni and a galaxy of French

contemporaries. As the subject

matter of

Salome has lost its power

to shock, critics of the opera have tended

to discern kitsch rather than immorality

beneath the dazzling surface of Strauss’s music,

though it has never been easy to decide what portion

of the blame for this may be laid at the

composer’s door. Behind this

lurks the

awkward question whether the

operatic

Salome should be seen as

anything more than a musical extension of

Wilde’s creation.

From play in prose to Literaturoper

Salome’s

historical significance

resides in large measure in

the way it marks an important

stage (alongside Debussy’s Pelléas

et Mélisande and the

underrated Ariane et

Barbe-Bleue of Dukas) in

the evolution of

post-Wagnerian music drama

into what German critics have

termed Literatur-oper.

The most obvious sign of this

is the means by which Strauss

solved the problem of finding

a librettist, by setting

Hedwig Lachmann’s translation

as it stood (albeit with very

substantial cuts); opera's

traditional verse, which even

Italian verismo lacked

the nerve or inclination to

discard, was rejected in

favour of prose. The prose

libretto thus entered the

opera house not in the service

of realism but in the guise of

the symbolism of Maeterlinck

and the “poetic” childishness

of Wilde. That Wilde wrote his

play in French, partly under

the influence of Flaubert,

Mallarmé and their treatments

of the Herodias story, helps

to stress the extent to which

Strauss responded to a

modernist, international

aesthetic (a point not lost on

certain critics of a more

narrowly nationalist bent);

when he saw Lachmann’s

translation on stage in 1902,

it was in Max Reinhardt’s

Kleines Theater, a forum for

modern theatre that already

looked forward to the more

experimental techniques of

Expressionism. It was on this

occasion that the cellist

Heinrich Grünfeld suggested

the possibility of an opera,

to which Strauss replied that

he was already composing it;

the play had been sent to him

in 1901 by the Viennese poet

Anton Lindner, who also made

some attempts to versify

Lachmann’s translation as the

traditional kind of libretto.

But after that Strauss

responded simply to Lachmann’s

opening sentence, “Wie schön

ist die Prinzessin Salome

heute nacht!” (possibly as

late as July 1903), and began

to compose, while at the same

time purging the play of many

“purple passages”, of which he

had no need, having possessed

a facility with purely

orchestral “purple passages”

since Don Juan.

The implications of Strauss`s

decision to create an opera

from a play in prose were

diverse. Already in Wagner,

the relationship between word

and music had been

reinterpreted, ostensibly in

favour of a literary and

psychological approach to

opera that stood apart from

both the older operatic

aesthetic and the “critical”

approach of present-day

developments (which accord

more with the central role

allotted to a director than

Wagner would probably have

appreciated). In Salome,

the drama is Wilde’s to the

extent that the music reflects

the text. In this critics have

seen problems which go beyond

Strauss’s opera. Wilde’s play

is not easily translated, as

the problems of its English

version make plain; this is

not simply a matter of the

“schoolboy faults” of Lord

Alfred Douglas in attempting

the first translation, but

rather a question of

reproducing the “music” of the

French original (which Wilde

in De profundis

insisted upon when criticizing

Douglas’s misguided efforts).

It is arguable that Lachmann

failed similarly, though the

further argument of some

writers that the German

language was in itself an

inappropriate vehicle for

Wilde’s kind of word-music

seems foolish in view of the

quality of the lyrics (often

French-inspired) which were

being created at the time by

Hofmannsthal, George and

Rilke. The role of Lachmann,

who moved in anarchist circles

both from her own convictions

and from those of her

poet-husband Gustav Landauer

(later murdered for his part

in the Bavarian Soviet of

1919), serves as a reminder

not of the “music” of the

original but rather that the

“musicality” of Wilde was

contemporary with his

alignment of the cult of the

aesthetically beautiful and a

form of libertarianism in The

Soul of Man under Socialism.

But a central problem of the

metamorphosis of Salome from

dramatic to operatic heroine

was the extent to which verbal

music in Wilde’s sense was

compatible with real musical

values. At the heart of

Strauss’s creative achievement

lies the paradox of a literary

work - itself characterized by

the rejection of realism in

favour of verbal incantation -

subjected to a musico-dramatic

treatment that seemed to

reflect a modern blend of

realism and psychology. While

Wilde’s Salomé

“aspired to the condition of

music”, Strauss’s Salome

aspired to the condition of

literary drama.

Leitmotif in Salome

For Strauss the play was the

starting-point, inasmuch as he

wrote down many of his initial

motivic ideas into a copy of

the German text so as to

suggest various correlations.

But the composition of the

work (which was finished, with

the notorious exception of the

Dance of the Seven Veils, by

20 June 1905) qualifies this

in ways which are not

unfamiliar from Wagner. The

efforts of Wagner scholars

have heavily modified the

traditional picture of the

leitmotif; it is no longer

sufficient to explain music

drama with a guidebook of

representation motives. This

was always apparent in the

case of Tristan and Isolde,

the Wagnerian music drama

which Salome most

resembles. Just as Wagner in Tristan

avoided literalness in the

complexity of his treatment of

the musical motive, so Strauss

in Salome evolved a

technique of transformations

of context that is often more

remarkable than the variations

of musical shape. Thus many

figures in Salome make

a fetish out of the interval

of a third, sometimes major,

more often minor. Similar

figures in the later Elektra

stand fairly unambiguously for

the murdered Agamemnon, But in

Salome many of these

ideas resist definition and

lead to subtle connections;

the major-third motive to

which Salome sings “Ich bin

verliebt in deinen Leib,

Jochanaan!” later sinks into

the minor, adding both force

and atmosphere in various

timbres to the execution of

the Baptist, Herod’s sense of

disgust, and the final

crushing of Salome beneath the

soldiers’ shields.

The path to this brutalization

of an originally shimmering

motive lies in the various

other motives which begin with

a minor third, notably “Ich

will deinen Mund küssen,

Jochanaan” and the figure to

which Salome repeatedly

demands the head of the

Baptist. Yet it is a sign of

the indirection with which

Strauss treats the

musico-dramatic motive that

neither of these sentiments

first enters in conjunction

with its characteristic

musical shape. Verbal and

musical motives find one

another as Salome’s obsession

grows. Her music when

demanding the head of

Jochanaan is presented in

almost incoherent dynamic

contrasts, the first

disorganized dawnings of

revenge as she crouches over

the cistern in which Jochanaan

is imprisoned. The demand

itself is presented as a

laughing throwaway, the

accompanying musical texture

of harp, celesta and clarinet

trill seeming to belong to the

laugh, or to the silver

salver, rather than to

Jochanaan’s head and its

imminent fate. It is only as

the dramatic conflict between

the beseeching Tetrarch and

Salome degenerates into

obduracy that the words “Ich

fordre den Kopf des Jochanaan”

move close to the musical

shape for which they were

seemingly predestined. By such

means Strauss keeps a fairly

primitive musical idea in a

state of flux. Even then,

however, he does not lose

sight of earlier stages in the

process, and the return of the

original major motive of

Salome’s infatuation in the

final monologue after the

climax at “Jochanaan, du warst

schön” turns the shimmer of

the motive into a texture of

celesta, harps and strings

whose liquidity is all the

more remarkable for the

immobility of the supporting

harmony; at such a moment it

is hard not to think ahead to

the silver rose in Der

Rosenkavalier.

The famous motive of two

fourths which at first stands

for certain aspects of

Jochanaan, is another instance

of a musical figure which

develops into something other

than a mere calling-card.

Ultimately it seems to evoke

the “geheimnisvolle Musik”

which Salome heard on seeing

Jochanaan. Yet by presenting

fragments of the motive before

Jochanaan appears, Strauss

suggests that Salome had been

ready for such “secret music”

before she fixed her obsession

upon the prophet. The musical

motive represents something

inchoate in this case, an

approximation to that almost

impossible intangibility which

earlier German Romantic

writers had felt to be at once

music’s true property and

goal. The two fourths of this

motive (which Schoenberg

bracketed with advanced

progressions in Mahler,

Debussy and Dukas) represent a

more radical novelty than the

chromatic sideslips of

Salome’s waltz-like entrance

theme; taken together, the two

types of ideas seem to

represent a world of

glittering surfaces and a

deeper reality lying

underneath. Salome’s tragedy

would seem to be that she

senses the reality but reaches

out to grasp it in a way that

is apparently superficial.

Here is one significant

tension between Strauss and

Wilde, since the love of

surfaces, the exaltation of

the aesthetic sensation, was

one of Wilde’s positives. What

is actually offered to Salome

by Jochanaan is a vision of

Christ on the Sea of Galilee

that is at once portentous in

its announcement, bland in its

harmony and insipid in its

melodic line; this Galilean is

pale indeed. Granted that

Strauss knew his Nietzsche and

had renounced conventional

religion, it is hard to avoid

the suspicion that the music

for Jochanaan and the

Nazarenes is not so much the

failure to which critics have

repeatedly referred but a

barely concealed contempt. The

secret music of Salome’s

imagination is of a complexity

that Jochanaan cannot fathom

and that Wilde’s fails to do

more than name; the true

climax of Jochanaan’s dialogue

with Salome is not to be found

in the outpourings of

Strauss’s orchestra (which

reaches new heights of frenzy

even for him, as the Baptist

retreats into the cistern

cursing his antagonist) but in

the “toneless shudder” of

“Niemals, Tochter Babylons,

Tochter Sodoms,... Niemals!”

Man’s potential fear of the

sensually aroused woman was

never more numbingly evoked.

The silence does not last

long. Later, however, Salome

does kiss Jochanaan’s head in

a prolonged silence broken

only by the soft swelling of a

directionless sonority of

nauseous intensity; at such

moments the childish

repetitions and banalities of

Wilde’s play find a reflex

commentary in Strauss’s

orchestra.

The sensuous façade

Conventionally such moments in

Strauss are classed as aspects

of his gift for illustration.

The orchestration of Salome

affords numerous examples of

pictorial detail, notably in

the scenes of violence, where

for many critics a new depth

of tastelessness was plumbed

by the use of short stabbing

strokes on high double basses

for the heroine’s irregular

breathing while the execution

is being carried out in the

cistern. Salome abounds

in such novelties. But the

orchestral and harmonic daring

are only one aspect of the

sensuous façade of the opera.

Salome is a testament

to the abundance of Strauss’s

melodic gifts as well as to

his illustrative facility, The

type of melody with which

Strauss operates is often

rather more traditional (or

banal, as harsher critics have

insisted) than his fame as

Wagner’s successor would

suggest. The musical motives

are frequently shaped into

relatively conventional

periods, and this is

particularly apparent in the

final monologue. It was Ernest

Newman’s belief that the music

for this monologue was

composed before earlier

sections based on the same

themes (such as the dialogue

between Salome and Jochanaan),

a view that probably

influenced Norman Del Mar when

he maintained that only with

the final monologue do words

and music seem to fit in the

most natural way. The unproven

theory might be crudely stated

in sonata terms: the “reprise”

was composed before the

“exposition”.

The sonata or symphonic

parallel was quickly pressed

into service to explain

Strauss’s technique and

structure in Salome.

Fauré’s comment is the most

famous, but also the most

glib: “Salome is a

symphonic poem with additional

voice parts”. Strauss’s

attitude to such comments was

equivocal; he recognized that

“unsuspecting critics” viewed

Salome (like Elektra)

as a“symphony with

accompanying voice parts”, but

felt that they did not

understand the extent to which

the symphonic organization

“conveyed the kernel of the

dramatic content”. That a

symphonic intelligence might

serve to shape music drama had

been recognized earlier by

Nietzsche in Richard

Wagner in Bayreuth, a

judgement that had passed into

the small talk of musical

criticism by Strauss’s day.

But Strauss had his own view

of the symphonic.

A page of reflections found

among the sketches for Also

sprach Zarathustra makes

quite clear that his idea of

the symphonic was not

dependent upon the kind of

thematic and motivic

development familiar in the

symphony of the 19th century;

the “briefest intimations” of

formal conflicts seemed to him

preferable to excessive

development of the type found

in Liszt. As a result, the

individual sections of much of

Strauss’s music seem more

elegantly formed than the

overall structure. He refused

to worry (as Mahler did) that

the “Dance of the Seven Veils”

would suffer for being

stitched together after the

composition of the rest of the

work. The periodic structures

of Salome’s monologue and

other sections enhance the

sensation of a sequence of

beautifully formed episodes;

if the work seems to have a

larger coherence, it may

simply be because the most

finished episodes come towards

the end. Even the conclusion

is a sudden interruption: the

final cadence of Salome’s

ecstatic kissing of the

severed head is cut short by

Herod’s capricious decision to

have her killed. As a result

the tonal scheme, which in

reality makes carefully

planned use of areas relating

to C and C sharp, seems no

less capricious. In such a

context, “symphonic” is a word

which can only be used in

relation to Strauss’s own very

idiosyncratic interpretation,

with which such contemporaries

as Mahler and Sibelius would

hardly have agreed. Forms are

as much part of the surface as

orchestration and waltz

rhythms.

The most striking aspect of Salome’s

episodic façade is the manner

in which Strauss turns the

five squabbling Jews into a

virtuoso scherzo, which he

described on a later occasion

as “pure atonality”; this

seems calculated to add

another dimension to the

general sense of scandal and

perversity which worried the

cast of Ernst von Schuch’s

Dresden company during

rehearsals. Sander L. Gilman

has pointed to the way in

which Strauss’s evocation of

Biblical Jews reads Wilde’s

text in a contemporary spirit,

thereby “subversively

contravening one of the basic

tenets of German

anti-Semitism, which saw the

Jews of the Bible, especially

of the New Testament, as

different from contemporary

Jewry.” According to Gilman’s

very subtle argument,

Strauss’s liberal Jewish

audience may have recognized

the despised “Eastern” Jews

from the ghettos in the

high-pitched hysterical

quintet, where

character-tenors of the same

kind as Herod outnumber a

solitary bass. An array of

stereotypes dominates Herod’s

court: stage Jews, Nazarenes

who sing in that pious

diatonicism which 19th-century

opera thought suitable to

religion, and the dancing

Salome, whose mild exoticisms

are all too easily (if

mistakenly) choreographed as a

lascivious strip-tease. The

sequence between Jochanaan’s

cursing of Salome and her

demand for his head is a diverlissement

of grotesques, a

representation of kitsch which

can hardly help being kitsch

itself, albeit of a

technically superior kind.

Whereas the pretension in

Wilde resides in the claim of

his childish sentences to

being musical, Strauss

exhibits the superficiality of

his characters by dwelling on

musical and dramatic clichés

swollen to pretension by the

amplifying voice of his

orchestra. There are

inevitably points of aesthetic

contact between Wilde and

Strauss, but as a whole Salome

demonstrates the problems

inherent in composing an opera

to a text which itself aspires

to music. The play is as

curiously innocent in its

presentation of hysteria,

obsession and cruelty as

Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et

Mélisande; whereas

Debussy strove to capture the

innocence as well as the

cruelty, Strauss took a more

robust interest in uncovering

the psychology of characters

who are infected by the

cruelty of the theme. As a

result, his opera leaves Wilde

far behind in intensity, while

retaining a consuming interest

in the nature of the surfaces

that lend even to the

hysterical and depraved an

aesthetic glamour.

|

|

|