|

|

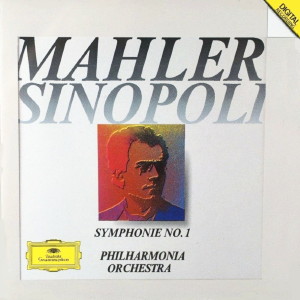

DG - 1

CD - 429 228-2 - (p) 1990

|

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie No. 1 |

|

57' 03" |

|

| -

1. Langsam. Schleppend.

Wie ein Naturlaut - Im

Anfang sehr gemächlich |

16' 24" |

|

|

| -

2. Kräftig bewegt, doch

nicht zu schnell - Trio. Recht

gemächlich |

8' 06" |

|

|

| -

3. Feierlich und

gemessen, ohne zu schleppen |

11' 55" |

|

|

| -

4. Stürmisch bewegt |

20' 29" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

All

Saints' Church, London (Gran

Bretagna) - febbraio 1989

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Recording

Engineer |

|

Hans-Rudolf

Müller |

|

|

Editing |

|

Oliver

Rogalla |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 429 228-2 | LC 0173 | 1

CD - 57' 03" | (p) 1990 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mahler`s

twenties -

the 1880s - were fairly

restless years. He worked as

a conductor successively in

Laibach (Ljubljana), Kassel,

Prague, Leipzig and

Budapest, often at odds with

his associates and

superiors, leading a

turbulent emotional life and

channelling emotion into

composition. His affair in

Kassel (1883-84) with the

singer Johanna Richter

helped to inspire not only

those passionate songs of

love and despair, the Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen

(to Mahler’s

own texts), but also the

First Symphony. And if one

love affair served to launch

the symphony, another (with

the wife of Carl Maria von

Weber’s grandson in Leipzig)

seems to have spurred it on

to completion in 1888. In

March of that year Mahler

wrote to a friend that the

work “has turned out so

overwhelming, it came

gushing out of me like a

mountain torrent! All of a

sudden all the sluicegates

opened!”

What we now know as Mahler’s

First Symphony was called

“Symphonic Poem in Two Parts”

when first performed in

Budapest in 1889: Part One

contained the first movement

and scherzo with, in

between, an Andante that

Mahler eventually discarded;

Part Two comprised the

funeral march and finale. For

the second performance, in

Hamburg in 1893, Mahler

reinforced the music’s

programmaticism with a

more specific title: "Titan,

a

tone-poem in the form of a

symphony".

By now the two parts and

the various movements all

had titles. Titan

was an early 19th-century

novel by Jean Paul Richter, and

although at no stage did

the symphony follow the

events of the book the

essential idea of an

heroic protagonist

revelling in nature and

struggling against the

deadening forces of

philistinism can clearly

be traced in the music.

Another quite distinct

programmatic source lies

behind the titles

successively given to the

slow movement, described

first as “in the manner of

Callot” (a French etcher

whom Mahler probably

encountered through E. T.

A. Hoffmann’s “Fantasy

Pieces in the Manner of

Callot”), then as “the

hunter’s funeral

procession”: this could

refer to an ironic woodcut

by Moritz von Schwind in

which animals bearing

torches and banners

accompany a coffin on its

way to burial. For the

Hamburg performance Mahler

also entitled the second,

Andante movement “Blumine”

- "flower

chapter". The movement was

derived from some

incidental music Mahler

had provided for Scheffel’s

play Der Trumpeter von

Säckingen

in 1884. It was only by

the time of the work’s

performance in Berlin in

1896 that the programmatic

titles were removed, along

with the “Blumine”

movement. The work was now

called simply "Symphony

in D major for large

orchestra".

Mahler presumably decided

that the programme, added

initially in the interests

of comprehensibility, and

to justify to disconcerted

audiences the music’s raw

emotionalism and extreme

changes of mood, was more

of a hindrance than a

help. The work had to

stand or fall by its

formal as well as

emotional conviction. By

Brahmsian standards it is

certainly heterogeneous,

very much the work of a

young composer whose

previous efforts had been

almost entirely vocal -

the large-scale cantala Das

klagende Lied and

the collections of songs,

Lieder and Gesänge

and Lieder eines

fahrenden Gesellen.

In its expansiveness

Mahler’s symphony is

closer to Bruckner than to

Brahms. Yet its

exploration of the ironic,

the macabre, the hectic

could scarcely be less

Brucknerian. Mahler owed

more to the opera house

than the organ loft, and

although precedents for

programme music in

symphonic form can be

found - in Liszt as well

as lesser composers like

Goldmark and Raff - the

musical atmosphere he

created from the

confrontation between his

own highly personal,

songlike material and the

hallowed formal categories

and procedures of the

traditional symphony was

already distinctive and

arresting.

Part of the title

originally given to the

first movement was "From

the days of youth",

and its extended slow

introduction presents a

ravishing aural picture of

the world coming to life.

The hushed opening is

marked "Like a sound of

nature",

and as the germinal

melodic interval of a

descending fourth speeds

up it acquires the

scarcely necessary

inscription “Like the call

of the cuckoo”. Yet these

details, along with a

principal theme taken from

the second and most

cheerful of the Gesellen

songs, are part of a

substantial, effectively

organized form. Of

particular significance is

the gradual transformation

of minor tonality into

major as the first

movement proper gets under

way. This modal contrast

serves to generate tension

in the development section

and to prepare for the

appearance (in the remote

key of F minor) of the

agitated theme that will

dominate the finale. As

far as the first movement

is concerned the potential

crisis represented by that

theme and its treatment is

defused: the cheerful,

pastoral material returns,

and the movement ends with

a brief, fast coda like a

burst of exuberant

laughter.

The second movement

derives its main idea from

another of the early

songs, “Hans und Grete”.

Though not labelled Ländler

by Mahler - the

programmatic title was "In

full sail" - it is a

particularly attractive

example of that folklike

dance form, at first

uncomplicated, with an

ebullient opening tune,

but developing some

tension in its second

half. After the more

reflective trio, with that

tonic F which provides the

main challenge to the

symphony’s basic

D-tonality, the Ländler

returns in abbreviated

form.

Programmatically, the slow

movement evidently

counters and rejects the

pastoral simplicity and

optimism which have

dominated the symphony so

far. Yet just as Mahler’s

expression of these moods

in the first two movements

was not devoid of

questioning and tension,

so his sombre, superbly

orchestrated funeral

procession provides its

own well-developed

contrasts. First there is

self-mockery, as the

orchestral round on “Frère

Jacques", initiated by the

marvellously eerie solo

double bass, yields to

material marked “with

parody” (a maudlin pair of

trumpets particularly

prominent). Later, there

is sublime, bittersweet

resignation, quoting the

final section of the Gesellen

songs with its stark

cadence cancelling major-key

warmth with minor-key

chill. After this the “Frère

Jacques” procession

resumes, and gradually

disappears into the

distance.

The finale

is the work’s most

ambitious movement. It

seems to have given Mahler

the most trouble (his

revisions to the earlier

movements were mainly of

orchestration) and its

form may well leave

something to be desired:

contrasts are extreme, the

most exciting moment of

harmonic resolution comes

at a relatively early

stage. Yet it is a vivid

depiction of what the

original, Dantesque title

described, as a journey

from Hell to Paradise:

from struggle, through

lyric reflection, to

renewed struggle and final

triumph. The thematic

links with the first

movement are underlined by

the recall of that

movement’s introduction at

the finale's

mid-point, before the

recapitulation of the

contrasting lyric melody

prepares the final victory

of “Paradise” over “Hell”,

and the apotheosis of the

introduction’s theme.

There may be as much of

hysteria as jubilation in

the concluding, prolonged

affirmation of the D major

tonic harmony: it was this

aspect of Mahler that

Shostakovich, notably in

his Fifth Symphony, would

take up and make his own,

Yet the excitement is

genuine. The youthful

Mahler, the music

proclaims, is serving

notice on the symphonic

tradition, and the rest of

his life would be devoted

to redefining that form

and giving it a uniquely

personal diversity of

scope and substance.

Arnold

Whittall

|

|

|