|

|

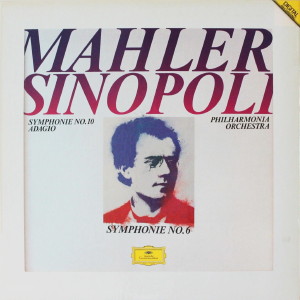

DG - 2

LPs - 423 082-1 - (p) 1987

|

|

| DG - 2

CDs - 423 082-2 - (p) 1987 |

|

| Gustav MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1

|

|

58'

34" |

|

| Symphonie No. 6 |

|

93' 12" |

|

| -

1. Allegro energico, ma non troppo.

Heftig, aber markig |

25' 08" |

|

|

| -

2. Scherzo. Wuchtig |

13' 33" |

|

|

| -

3. Andante moderato |

19' 53" |

|

|

| Long Playing 2 |

|

67'

08" |

|

| -

4. Finale. Allegro moderato -

Allegro energico |

34' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 10 |

|

32' 40" |

|

| -

Andante - Adagio |

32' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA |

|

| Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Watford

Town Hall, London (Gran Bretagna):

- settembre 1986 (Symphonie No. 6)

- aprile 1987 (Symphonie No. 10)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Günther

Breest |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann |

|

|

Editing |

|

Werner

Roth (Symphonie No. 6), Reinhild

Schmidt (Symphonie No. 10) |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 423 082-1 | LC 0173 | 2

LPs - 58' 34" & 67' 08" | (p)

1987 | Digital |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 423 082-2 | LC 0173 | 2

CDs - 58' 34" & 67' 08" |

(p) 1987 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie

No.

6

Since completing his

Fourth Symphony in August

1900, the most important

event in Mahler’s life had

been his introduction, on 7

November 1901, to Alma Maria

Schindler, whom he married

four months later. Already

he had begun work on the

Fifth Symphony which he

completed during their first

summer holiday together. in

Mahler's

chalet at Maiernigg on the Wörthersee.

The Fifth was a significant

advance on the Fourth

Symphony,

though it too had its

musical roots in what Donald

Mitchell - from this end of

the 20th-century - calls the

"Wunderhorn

years".

It was with the Fifth

Symphony that a new

direction in Mahler’s

musical thought was clearly

discernible, and nowadays

commentators tend to lump

Symphonies 5, 6 and 7

together, as a sort of

middle-period trilogy.

Because Mahler was, in the

early 1900s,

composing songs to

poems by Friedrich Rückert,

and because music from these

songs found a tenuous way

into these three symphonies,

Michael Kennedy (another

recent and perceptive Mahler

biographer) has called them

his "Rückert

symphonies". They do have in

common certain musical and

spiritual (also purely

physical) qualities which

stand out the more if one

contrasts any of them with,

on the one hand, the

innocent serenity of the

Fourth and on the other, the

monumental symphonic

organization and jubilant

faith of the

Eighth. But there are

thematic cross-references

throughout Mahler’s work,

not just to the Wunderhorn

and Rückert songs: indeed

sometimes Mahler`s eleven

symphonies (including Das

Lied von der Erde)

take on the aspect of one

integral, thematically

unified mega-symphony, a

musical equivalent of, say,

Homer`s Odyssey

(twelve books to Mahlerßs

eleven). The Sixth Symphony

stands at the centre of the

eleven, and it is the most

classically restrained in

form of them all, yet in

content apparently highly

autobiographical, an

imaginary presage of

personal doom, made at a

time when the composer was

healthy. happy, successful,

married with two infant

daughters and

an idolized wife. She

remembered him then as "a

tree in full leaf and

flower", at ease on holiday

in glorious countryside,

playing delightedly with his

babies, rowing on the lake,

swimming or sunbathing,

rambling the fields and

mountains in shabby old

clothes.

The literary content of the

Sixth Symphony is there,

chiefly in the Finale which

postulates a hero upon whom

fall “three hammer-blows of

fate”, the third of which

kills him. In the summers of

1903 and 1904, when Mahler

respectively began and

completed the work at Maiernigg,

he had no inkling that three

years later (when the Eighth

Symphony was complete) those

hammer-blows were to fall on

him: his eldest daughter

would die, he would be

relieved of his prestigious

post as artistic director of

the Vienna Court Opera, and

doctors would diagnose

lesions in his heart whose

prognosis was extremely

unpromising, All Mahler’s

music is partly

autobiographical, not always

about himself but about what

he had seen and heard and

experienced. The

hammer-blows had fallen upon

many others before who did

not deserve them. His Kindertotenlieder

were composed before he had

lost any children of his

own: he was moved by Rückert’s

poems because one of the

children commemorated was

called Ernst, the name of a

dear brother who died when

Mahler was a child.

It is more pertinent that in

the summer of 1903, during

first work on the Sixth

Symphony, Mahler set another

Rückert

poem, Liebst du um Schönheit

which, aside from the Fahrenden

Gesellen set of nearly

20 years earlier, remained

his only love-song,

extremely touching and

characteristic. Mahler

also told his wife (an

unreliable source of

information, but here

credible) that the second

subject of this symphony’s

first movement was intended

as a portrait of her - or

perhaps rather of Mahler’s

consuming love for Alma, a

more musical concept, though

such a jealous wife may have

feared it might be his love

for an earlier flame.

Mahler at first designated

his Sixth as a “Tragic

Symphony”; quite soon he

removed the nickname, as he

usually drew away attention

from extra-musical

references. He was right.

Some extra-musical

references in music cannot

be ignored; but most music

such as this was also

composed with the intention

that you and I will relate

it to our own personal

experiences, and thereby

find our lives in some way

enriched. We are likely to

find Mahler’s Sixth a more

sobering experience than,

say, his Fifth or Seventh

symphonies, though not

without moments of calm and

joy. I said that he

completed it in the summer

of 1904, but he continued to

tinker with the

orchestration until 1906

when he conducted the first

performance during the

Festival of the German

Musicians’ Union at Essen on

27 May, having previously

tried it out with the Vienna

Philharmonic Orchestra. He

revised it again in 1908,

after the score had been

published showing the slow

movement placed third after

the scherzo.

Conductors ever since have

exercised their personal

prerogatives about the

position of the middle

movements, though the

International Mahler Society

of today has opted for

Mahler’s finally expressed

preference for his original

intentions, the scherzo

being placed second. (That

is the sequence heard in

this recording.)

*****

Mahler’s

childhood was spent in the

countryside, near to a

military barracks. Even

after he became a

city-dweller through his

profession, his music

returned continually to

childhood memories. So this

symphony begins with the

sound of tramping feet, not

a funeral march as in the

Fifth Symphony, but a quick

march, heavy in beat,

eagle-eyed in authority,

severe. The arrival of the

first marchtune is so heavy

that it bids fair to bring

the regiment to a halt, so

passionate, even hysterical,

that the troops seem to

vanish. But no, an instant

later they are on the move

again, in full voice though

the tunes are several, often

simultaneous, and too

strenuously extended for any

usual vocal compass, with

trills and screeches and

precipitous plunges, plenty

of brass and drums.

If

too quick for a funeral,

this march is sufficiently

ominous to suggest the

doomed and the damned. It

disintegrates into a stern

drum rhythm, above it a

trumpet chord, major fading

into minor, like the sudden

passage from physical life

to physical death, a motto

of this symphony. A

sort of wan chorale for

woodwind, against remnants

of the march, leads to the

voluptuous outpouring of

what (rightly or wrongly) is

called the Alma theme, the

movement`s second subject,

grand, rich, clearly

articulated, not just a

flowing melody (though it is

that, as well), even more

sumptuous when repeated

after a curious, perfectly

prepared, reference to

Liszt’s E flat piano

concerto, hard to accept as

coincidence since the

musical atmosphere is

similar - Liszt put words to

his theme Das versteht

ihr alle nicht (“None

of you understands this”).

Then this vital march of a

theme subsides, and the

initial march resumes,

either with the repeated

exposition indicated by

Mahler, or by proceeding (pace

Mahler devotees) straight to

the development, bringing

abrupt string glissandos at

once, and the robust clink

of the xylophone

(a novelty for Mahler), diversely

exploited for some time,

while the march tune

infiltrates the Alma melody,

trying to conquer it in

favour of more rhythmical,

violent topics. Those are

dispelled, contrariwise, by

something else: the sound of

remote cowbells, tinkling celesta,

string tremolos, pastoral

fanfares, which Mahler

described as the most remote

sound heard by a climber at

the top of a mountain, viz

earth as apprehended by

those moving towards heaven.

This was certainly a memory

from Mahler’s extreme youth,

rather than from holidays at

Maiernigg, and it broadens

the conspectus of the

symphony’s content, bringing

it into

line with the whole of

Mahler’s auditory life and

creative work, I think (the

cowbells will be heard

again, and in later music by

Mahler). The vision of

earthly man’s nearest

approach to Heaven continues

until it is interrupted by a

return of music derived from

the initial quick march

(especially the Liszt

reference), becoming more

and more intensive until the

recapitulation which begins

triumphantly in A major, as

if victory were won - only

to sink into expected A

minor, for a far from

literal re-statement of

themes, so intense an energy

have they set up. The

coda

begins in despair but again

rises to triumph, through

the inspiration of the Alma

theme.

The Scherzo also begins with

loud pulsating basses, not

for a march but a

triple-time movement,

belonging to devils rather

than soldiers, grotesque and

predatory in their glee

(xylophone again). The harsh

atmosphere is not far from

that of the previous

movement (one can appreciate

why Mahler contemplated

putting the slow movement

here, in a contrasted key),

but more burlesque and

remorseless. A particularly

insistent set of chords is

to turn into the basis of

the Scherzo’s trio section.

almost at once. The repeated

notes fade into a slower,

gracious, “grandfatherly”

(Mahler’s word) dance, very

irregular in metre,

decidedly comic. It looks

forward to the second

movement of Mahler’s Ninth

Symphony, back to that of

the Second (a wholly

convinced Ländler,

as this is definitely not),

and portrayed, if we trust

Alma, the perilous first

toddling by the lake of the

Mahlers’ baby daughters.

There are loud interruptions

- adult rescue, or something

quite else? The harsh

Scherzo tries to return, but

the Trio is resumed and

optimistically extended,

though its repeated notes

turn sour before the Scherzo

returns properly. The

tottering children are

sighted near the end, but

quietly brushed away, not, I

think, from superstitious

pessimism, but rather

because they were an

episode, not part of the

unpleasant main section of

the movement.

According to Mahler`s first

and last thoughts, there now

follows the slow movement,

Andante in E flat

major (musically the key

most remote from A). We are

back in idyllic countryside,

near to the Alma world (also

suggested in the Adagietto

of Symphony 5, and in the

penultimate song of Kindertotenlieder,

in the Night-music movements

of No. 7 as well). A rocking

figure is involved, and a

melancholy tune for cor

anglais. These materials

alternate gently,

transformed by one another

at each reappearance. The

cowbells and celesta return

too, to impress the rarified

air still more closely upon

the ear, and a considerable

intensity will be created,

leading to a release of

Brahmsian calm sequences

that ignite into something

like passion before the

gentle close.

The slow

movement ended in E flat

major, whence it started.

The Finale begins in C minor

(same key-signature).

Musical people will agree

that the flat-keyed Andante

belongs here rather than

between two A minor

movements, unless Mahler

wanted violent

key-contrasts, unlikely in a

symphony so carefully

classic and self-controlled

in design. This now is the

movement of tragedy, a sostenuto

introduction with a C minor

violin melody, compounded of

hope and despair, including

a clear reference to the

Alma theme from the first

movement, a back-reference

to the major-minor Fate

motto on trumpets with

drum-thumps, a soft and

markedly rhythmical groan

for bass tuba (the clarinet

skirl with it comes from the

Scherzo), a horn call

looking directly back to the

Auferstehn theme of

Mahler 2, then a soft and

sombre chorale tune for wind

and brass. We are close to the funerary.

world of the Second

Symphony. The major-minor

trumpet motto warns again.

The music stirs towards an

Allegro tempo and a

different quick-march, still

linked with the

first-movement ideas (and

looking forward to the

Eighth Symphony as well).

Development comes thick and

last, for old rather than

new themes.

This section IS interrupted

by a return to the

introductory music, now in D

rather than C minor,

unwillingly urged by its

themes back to a fast tempo,

Always the swirling

introductory music, and the

major-minor trumpet motto

intervene, and the

hammerblows, only twice:

Mahler wrote the third blow

into the score, but insisted

that, being lethal, it must

not be played. After the

unheard third blow there

remains only the coda,

a slow fugato on the

introductory theme whose

aimless striving is cut

short forever by the trumpet

motto and the drum rhythm.

The orchestra is huge,

though sparely used; this

is surely Mahler’s most

succinct, self-contained

symphony.

William

Mann

Symphonie

No. 10

Mahler’s principal energies

during the summer of 1910

had to be concentrated on

preparations for the

forthcoming first

performances of his Eighth

Symphony in

Munich during September. He

was however able to take a

short holiday in his cottage

at Toblach in the eastern

Tyrol (he had given up

Maiernigg when his daughter

died), and there he sketched

the five movements of his

Tenth Symphony, and made a

fair copy of the first

movement in full score. His

work was interrupted by his

wife’s nervous breakdown and

an ensuing crisis in their

marriage, which prompted

Mahler to consult the

psychologist Siegmund Freud.

The crisis was happily

resolved, but Mahler had no

more time to work at his

Tenth Symphony: after the

Munich performances of the

Eighth, he needed to revise

his Second and Fourth

symphonies before returning

to New York where the

Philharmonic season, under

his directorship, started in

November. Before that season

was over, Mahler fell ill

with blood poisoning. He was

shipped back to Europe, but

died in a Vienna sanatorium

on 18 May 1911.

At first his widow clung

secretively to the

manuscript of the unfinished

Tenth Symphony. In 1924 the

musicologist Richard Specht

persuaded her to have it

published in facsimile, so

that other musicians might

learn from the drafts. Her

son-in-law, the composer

Ernst Křenek,

prepared a performing

edition of the first and

third movements which were

conducted in Vienna by Franz

Schalk and Alexander

Zemlinsky; all three made

questionable adjustments to

the scoring, as was shown

when this score was

published in the United

States. The International

Mahler Society in Vienna has

now published the first

movement -

often loosely described as

the Adagio though it is

properly Andante and Adagio,

the two tempi alternating -

exactly as Mahler left it. This

is frequently played on its

own as here, a tantalizing

sample of Mahler’s

unfinished Tenth Symphony.

It proposes two ideas: the

unaccompanied andante

melody for violas, lonely

and apparently meandering;

then the rich, warm adagio

melody for swooping violins

underpinned by mysterious

trombone chords, and given a

more cheerful, dance-like

pendant. The two groups of

ideas alternate at first,

each acquiring variants and

new counterpoints (an early,

durable variant is the

discovery that the themes

can effectively be stood on

their heads, yet remain recognizable),

until in the developmental

middle section both groups

are brought together. The

upshot is that two widely

distanced violin lines,

related to the lonely andante

melody, are dramatically

scooped up by a huge chord

of A flat minor, splashing

harps and all, upon which

the brass float a passionate

yet celestial chorale. This

moment of sublime euphony is

almost at once confronted by

an equally huge discord,

pierced at the top by very

loud trumpet,

the discord (nine notes, not

all twelve) repeated before

the strings climb down for a

still developing

recapitulation that finally

climbs back aloft in a mood

of tranquil resignation.

William

Mann

|

|

|