|

|

DG - 4

LPs - 2741 019 - (p) 1983

|

|

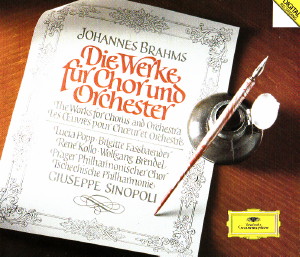

| DG - 3

CDs - 419 737-2 - (p) 1983 |

|

|

| DG - 2

LPs - 410 697-1 - (p) 1983 |

|

| DG - 1

LP - 410 864-1 - (p) 1983 |

|

| DG - 1

LP - 410 865-1 - (p) 1983 |

|

| Johannes BRAHMS

(1833-1897) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1

|

|

52'

25" |

|

| Ein deutsches

Requiem, Op. 45 |

|

75' 40" |

|

| Nach Worten der

Heiligen Schrift für Soli, Chor

und Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

1. "Selig sind, die da Leid tragen"

- Ziemlich langsam und mit Ausdruck

(Chor) |

12' 13" |

|

|

| -

2. "Denn alles Fleisch, es istwie

Gras" - Langsam, marschmäßig · Un

poco sostenuto · Allegro non troppo

(Chor) |

15' 35" |

|

|

| -

3. "Herr, lehre doch mich" - Andante

moderato (Bariton und Chor) |

10' 24" |

|

|

| -

4. "Wie lieblich sind Deine

Wohnungen" - Mäßig bewegt (Chor) |

7' 24" |

|

|

| -

5. "Ihr habt nun Traurogkeit" -

Langsam (Sopran und Chor) |

6' 49" |

|

|

| Long Playing 2 |

|

47'

12" |

|

| -

6. "Denn wir haben hie keine

bleibende Statt" - Andante · Vivace

· Allegro (Bariton und Chor) |

10' 49" |

|

|

| -

7. "Selig sind die Toten" -

Feierlich (Chor) |

12' 38" |

|

|

| Triumphlied,

Op. 55 |

|

23' 45" |

|

| Offenb. Joh.

Kap. 19 - für achtstimmiger Chor

und Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

1. "Hallelujah! Heil und Preis" -

Lebhaft, feierlich (Chor) |

7' 31" |

|

|

| -

2. "Lobet unsern Gott, alle seine

Knechte" - Mäßig belebt · Lebhaft ·

Ziemlich langsam, doch nicht

schleppend (Chor) |

8' 21" |

|

|

| -

3. "Und ich sahe den Himmel

aufgetan" - Lebhaft · Feierlich

(Bariton und Chor) |

7' 43" |

|

|

| Long Playing 3 |

|

38'

50" |

|

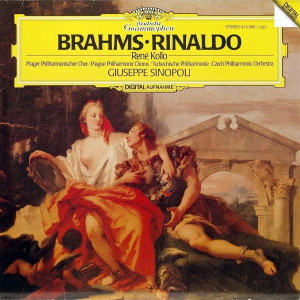

| Rinaldo,

Op. 50 |

|

38' 50" |

|

| Kantate von

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe für

Tenor Solo, Männerchor und

Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

1. "Zu dem Strande! Zu der Barke"

(Allegro-Poco Adagio-Un poco

Allegretto-Moderato-Allegro-Allegro

non troppo-Poco sostenuto) |

22' 37" |

|

|

| -

2. "Zurück nur! zurücke" (Allegretto

non troppo-Andante con moto e poco

agitato-Allegro con fuoco-Andante) |

10' 09" |

|

|

| -

3. Schlußchor: "Segel schwellen"

(Allegro-Un poco tranquillo-Vivace

non troppo) |

6' 00" |

|

|

| Long Playing 4 |

|

53'

51" |

|

| Alt-Rhapsodie,

Op. 53 |

|

14' 21" |

|

Fragment

aus Goethes "Harzreise im Winter"

für Alt, Männerchor und Orchester

|

|

|

|

| -

"Aber abseits wer ist's?"

(Adagio-Poco Andante-Adagio) |

14' 21" |

|

|

| Nänie,

Op. 82 |

|

14' 12" |

|

| von Friedrich

von Schiller für Chor und

Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

"Auch das Schöne muß sterben!"

(Andante-Più sostenuto-Tempo primo) |

14' 12" |

|

|

| Schicksalslied,

Op. 54 |

|

16' 35" |

|

| von Friedrich

Hölderlin für Chor und Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

"Ihr wandelt droben im Licht"

(Langsam und

sehnsuchtsvoll-Allegro-Adagio) |

16' 35" |

|

|

| Gesang

der Parzen, Op. 89 |

|

8' 43" |

|

| von Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe für

sechstimmigen Chor und Orchester |

|

|

|

| -

"Er fürchte die Götter das

Menschengeschlecht!" (Maestoso) |

8' 43" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lucia POPP, Sopran

(Op. 45) |

PRAGER

PHILHARMONISCHER CHOR |

|

| Wolfgang BRENDEL,

Bariton (Opp. 45 & 55) |

Lubomir Matl, Chorus

master |

|

| Brigitte FASSBANDER,

Alt (Op. 53) |

TSCHECHISCHE

PHILHARMONIC |

|

| René KOLLO, Tenor

(Op. 50) |

Giuseppe SINOPOLI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Rudolfinum,

Praga (Cecoslovacchia):

- 25/27 marzo 1982 (Opp. 53, 82,

54 & 89)

- 25 agosto / 3 settembre 1982

(Opp. 45, 55 & 50 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Hans Hirsch |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Wolfgang

Stengel |

|

|

Balance

Engineer |

|

Karl-August

Naegler |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 2741 019 | LC 0173 |

4 LPs - 52' 25", 47' 12", 38' 50"

& 53' 51" | (p) 1983 | Digital

Pubblicazioni separate:

- Deutsche

Grammophon | 410 697-1 | LC 0173 |

2 LPs - 52' 42 & 48' 42" | (p)

1983 | Digital | Opp. 45, 54 &

89

- Deutsche

Grammophon | 410 864-1 | LC 0173 | 1

LP - 51' 46" | (p) 1983 |

Digital | Opp. 53, 82, 55

-

Deutsche Grammophon | 410 865-1 |

LC 0173 | 1

LP - 38' 50" | (p) 1983 | Digital

| Op. 50

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon | 419 737-2 | LC 0173 |

3 CDs - 63' 43", 67' 06" & 62'

50" | (p) 1983 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Co-production

with Supraphon, Praha

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EIN

DEUTSCHES REQUIEM (A

GERMAN REQUIEM)

In 1853, the

year in which Johannes

Brahms, at the age of

twenty, experienced a

decisive turning-point in

his life, Robert Schumann

wrote the following

prophetic words about him:

“When he shall lower his

magic wand in the place

where the powers massed in

the chorus and orchestra

lend him their strength

there shall be vouchsafed us

yet more wondrous prospects

into the secrets of the

spirit world.” Fifteen years

later, when Brahms’s German

Requiem was given its

first performance on Good

Friday, 10 April 1868, in

Bremen Cathedral, Schumann’s

‘prophecy’ was fulfilled.

This was the first work in

which Brahms ventured into

the field of music for

large, mixed vocal and

orchestral forces, and at

the very first attempt he

provided proof of his

mastery in handling “the

powers massed in the chorus

and orchestra”. In that

essay of 1853, “New Paths”,

Schumann had also indirectly

referred to Brahms as the

heir of Beethoven (and

elsewhere he was explicit in

doing so). However, in the

particular area of religious

music, at least, Beethoven

stayed with the traditional

liturgical text of the Mass,

whereas Brahms made a

complete break with

liturgical tradition in both

the content and the form of

his German Requiem.

A consistent ‘tone’ prevails

in all seven movements of

the Requiem, which

provides a firm basis for

the unity of the cycle.

Attempts to demonstrate that

symmetry is the predominant

formal conception - with the

fourth movement a central

pivot - do not meet the

measure of the work. A

description of the creative

process that Brahms pursued

in this great oratorio-like

work could almost begin with

the statement “in the

beginning was the Word”. The

consistency of mood of the

biblical texts that Brahms

selected and placed in his

own chosen order is the

first factor contributing to

the impression of perfect

formal integrity. The

different emphases and

nuances of the subjects that

come to the fore in the

individual movements -

consolation, patience, hope,

joy, grief, trust,

redemption - provide the

opportunity for the music to

create variation but there

is nevertheless a sense of

one underlying emotion

common to them all, which,

as Siegfried Kross has aptly

commented, gives the work an

unwritten dedication: “To

them that mourn, for they

shall be comforted.”

The biblical

text does more than ensure

the inner cohesion of the

cycle in respect of its

subject matter; in

combination with techniques

from the traditions of

Protestant choral music it

leads to the creation of

musical formulae which are

determined by the nature of

the words. The various ideas

and images of the text are

extracted from the whole for

the purposes of their

musical setting: single

lines or groups of lines are

repeated over and over

again, imbuing the biblical

text so to speak with an

inner motion, in forms of

imitation and fugue,

exchanged antiphonally

between the different

sections of the choir or

sung as stanzas; like an

object of great value the

lines are turned about to be

viewed from every side,

moulded in new musical

shapes, plumbed for every

atom of meaning. Then the

following line of the text

is introduced into the

texture in the manner of a

motet, to undergo similar

treatment.

In View of the

primacy of the words, it is

no wonder that Brahms took

great pains to make them

audible. A German

Requiem is one of

those rare choral works

whose texts can be

understood even at the first

hearing. The fifth movement

(which Brahms did not write

until after the premiere in

Bremen) is exceptional in

that two different lines of

the text are sung

simultaneously: while the

soprano soloist is still

singing the final words of

the opening excerpt, “Und

eure Freude soll niemand von

euch nehmen”, the chorus

starts to sing a line

reserved for it alone, “Ich

will euch trösten, wie einen

seine Mutter tröstet”.

However, both these lines

are also delivered elsewhere

on their own, so the

principle of audibility is

upheld. At the end of this

movement Brahms has brought

the vocal lines of the

soprano soloist and the

chorus so close together,

above all in respect of

rhythm, as to make the words

“wiedersehen” (“see [you]

again”) and “trösten”

(“comfort”) almost identical

in sound: a subtle means of

conveying to the listener

the meaning of these central

tenets of Christian faith.

RINALDO

In Rinaldo

Brahms came closer than in

any other work to writing an

opera, In this cantata, the

composer, who spent many

years looking for a libretto

that would suit him as the

basis for an opera, created

a piece that requires

listeners to imagine a scene

and to perceive interior and

exterior actions experienced

by characters who are

presented through the medium

of sung dialogue. In fact,

the ‘action’ ‘takes place’

in two different scenes,

both of them thoroughly

typical of the Romantic

theatre: the distant island

where Armida casts her

spells of love, and theship

at sea which carries the

hero, released from the

enchantment, back to a life

of action.

The subject of Rinaldo

comes from Torquato Tasso’s

great epic poem, published

in 1581, “La Gierusalemme

liberata, overo il

Goffredo”. Rinaldo is a

knight who takes part in the

crusade in which, under the

leadership of Godfrey of

Bouillon (Tasso’s Goffredo),

Christians liberated

Jerusalem from pagan

(Islamic) rule. As the

Christians are encamped

outside Jerusalem, the

seductive enchantress Armida

appears in their midst, sent

by the Prince of Darkness to

bewitch the knights. At the

sight of Rinaldo, the most

heroic and noble of the

Christians, Armida is

herself overcome with

passionate longing; she

transports him and herself

to an island in the remotest

part of the ocean. Godfrey

dispatches other knights to

free Rinaldo and bring him

back. Armida is unable to

keep him at her side; she

destroys the enchanted

island and swears revenge.

She fights in battle on the

side of the pagans against

the Christians, and is

wounded by Rinaldo. Instead

of killing her, Rinaldo

converts her to Christianity

and eventually takes her

back to Rome as his Wife.

The story provided a subject

for many operas, such as

Lully’s “tragédie lyrique” Armida

et Renaud (1686),

Hande1’s opera Rinaldo

(1711) and Gluck’s “drame

héroïque”Armide

(1777). In 1863 Brahms came

across Goethe’s Cantate

Rinaldo, written in

1811 for Prince Friedrich of

Gotha, who possessed a

pleasant tenor voice. The

text concerns only a tiny

segment of the story of

Rinaldo and Armida, and

concentrates on a single

aspect of it. It begins at a

point when Armida’s

enchantment has already been

broken, and she is present

only in the memory of

Rinaldo, while his fellow

knights urge him to return

with them. It ends as their

ship approaches the shores

of the Holy Land and the cry

is raised: “Godofred und

Solyma°” (“Godfrey and

]erusalem!”) The particular

idea that interested Goethe

was the mystery of

transformation. It was only

when he was enchanted that

Rinaldo believed he was

alive. His awakening by the

knights signifies death to

him: “Im Tiefsten zerstöret,

/ Ich hab’ Euch vernommen; /

Ihr drängt mich zu kommen. /

Unglückliche Reise! /

Unseliger Wind!”

Brahms set Goethe’s text

without alterations. He gave

the title “On the high seas”

to the second scene, but

even that is implicit in the

text. True to the spirit of

the dramatic poem, the music

presents above all the inner

action, depicting its

development in a series of

expansive episodes. Thus

Rinaldo’s recent loss of his

own identity in Armida’s

enchanted world is presented

in the form of an ecstatic

recollection of the

beautiful and beloved woman;

three lines particularly apt

to a climax (“Sobald sie

erscheinet / In lieblicher

Jugend, / In glänzender

Pracht”) are repeated by

Brahms and placed so that

they form the conclusion of

Rinaldo’s great aria, where

the powerful entry of the

chorus of knights with

“Nein! nicht länger ist zu

säumen!” immediately

afterwards adds to the

dramatic impact. The two

turning points of the drama

provided by the text - the

sight of the reflection in

the “diamond shield” and the

vision of the “she-demon”

Armida - are rendered

musically with fascinating

rightness. A subito

pianissimo together

with the bleak sound of the

strings playing a single

note over four bare octaves,

with a very soft

interpolation on two

trumpets, gives the moment

of looking in the mirror an

expression of suppressed

terror. The second turning

point leads from a pianissimo

to a fortissimo, but

the role that effect plays

in depicting the horrifying

vision that comes to Rinaldo

after his cruel awakening is

overshadowed by the harmonic

effect of resolving a plain

chord of A minor onto the

augmented triad A flat-C-E.

This mysterious-sounding

triad, played piano,

perhaps represents the

injury done to the image

preserved in Rinaldo’s

memory. Immediately

thereafter the music

‘explodes’ in an Allegro

con fuoco, which

depicts the different image

of Armida as she was last

seen, dealing destruction

all about her. The work

closes with a chorus in the

heroic key of E flat major.

Rinaldo joins in, no longer

at odds with his fellow

knights, but singing in

unison with the chorus

tenors - a simple metaphor

for his return to their

number.

ALT-RHAPSODIE

(ALTO RHAPSODY)

Brahms’s Alto

Rhapsody is one of those

works inspired by a specific

personal experience, which

can only be properly

appreciated if the

experience in question is

known. In the summer of 1869

Brahms fell in love with

Clara Schumann’s

twenty-four-year-old

daughter Julie, but he kept

his feelings so perfectly

concealed that the Schumann

household was able to

proceed with the

preliminaries of Julie’s

engagement to Count

Marmorito, without anyone

suspecting that, or how, it

might affect Brahms. He

learned of the engagement in

September, and the news

struck him a deep blow.

Shortly afterwards he called

on Clara to give her the

Alto Rhapsody. “He called it

his wedding song”,

she wrote in her diary. The

“profound pain in the text

and the music” moved her

more than any work he had

written for a very long

time.

Beginning with a diminished

second-inversion chord, the

piece reflects in its

extreme harmonic tensions

the emotional anguish and

psychological torments of a

poem of the Sturm und

Drang. The poem

“Harzreise im Winter” dates

from 1777; in 1820 Goethe

provided an explanatory

comment, according to which

the three stanzas set by

Brahms refer to one of the

many young men who had

succumbed in the 1770s to

“the sickness of sensibility

prevalent at that time” and

bared their souls to the

author of Werther in

“repeated and importunate

outpourings”. Brahms was

probably not acquainted with

the poet’s later, cooler

view of the poem. To him the

verses were the vehicle he

needed for the expression of

his state of mind. He

immersed himself in their

sombre images and produced a

tone poem that in its

content and its form is a

worthy counterpart to the

original poem.

The three stanzas divide the

music into three sections,

which subtly differ from

each other in time (4/4 -

6/4 - 4/4), key (C minor - C

minor - C major) and tempo

(Adagio - Poco Andante -

Adagio). The first two

stanzas are sung by a

contralto soloist

accompanied by the

orchestra, and a four-part

male-voice chorus is added

in the third. If the move

from the minor to the

brighter major mode creates

a sense of a partial

relaxation in the

predominantly tense mood of

the work, the effect is

enhanced by the hymnlike

character of the closing

section. Goethe’s comment on

this stanza, referring to

the poet in whom the sight

of the barren winter

landscape has brought to

mind “the image of the

lonely youth, hostile to man

and to life”, was: “His

heartfelt sympathy is poured

out in prayer.” Brahms, by

introducing the chorus,

elevates the prayer of the

individual to a hymn of

human fellowship. In the

repetition of part of the

last stanza the stark

biblical image of “dem

Durstenden in der Wüste” is

replaced by the human

consolation of “So erquicke

sein Herz!” and so the

emphasis on release and

reconciliation is maintained

to the last note.

SCHICKSALSLIED

(SONG OF DESTINY)

Brahms’s

setting of Hölderlin’s poem

is a rare instance of a

composer not merely placing

an arbitrary interpretation

on words but explicitly

contradicting a poet’s

statement. What appears at a

first glance to be a matter

of formal completion - the

reprise of the orchestral

introduction at the end of

the work - turns out to be

the composer’s protest

against the content of the

poem.

In a letter to Karl

Reinthaler, who had

conducted the second

performance of the Requiem

in Bremen, Brahms wrote in

October 1871: “As we’ve

alreadz discussed enough: I

am saying something that the

poet does not say, and it

would certainly be better if

what is missing had been the

most important thing for

him.” And a short time

later: “And even if it is

perhaps possible to argue

that the poet doesn’t say

the most important thing, I

still don’t know if it can

be understood as things

are.” It is not difficult to

see what Brahms regarded as

the “most important thing”

which was missing in the

poem. Hölderlin’s

“Schicksalslied” expresses

the contrast between human

existence, with its unending

pain and continual

uncertainty, and that of

“celestial beings”, who

dwell above the clouds in

blessed peace and eternal

clarity, without offering

any prospect of release for

humanity. Hölderlin’s poem

ends with the last line of

the ‘human’ stanza,

“Jahrlang ins Ungewisse

hinab”, but Brahms follows

this with a return of the

orchestral prelude that

introduced the ‘celestial’

stanzas, and thus appends to

fatalistic portrayal of

human existence a

declaration of faith that

some part of the peace of

God will fall to men.

He spent some time in the

search for the right ending

for the work. When the score

was already written out in

full, he suddenly flirted

with the idea of returning

to his earlier version, in

which individual words and

lines were repeated by the

chorus, but Hermann Levi’s

objections were so emphatic

that he decided to abide by

the purely instrumental

close. Some doubts remained:

“It’s

- a silly idea... It’s

perhaps a failed experiment”,

and “The musician would do

better to beware of his own

thoughts”; but the idea of

confronting a pre-Christian

view of fate from the

perspective of the Sermon on

the Mount was so important

to him that he decided to

make no further changes.

TRIUMPHLIED

(SONG OF TRIUMPH)

France

declared war on Prussia on

19 July 1870. It was only a

matter of weeks before

German victory was assured.

Napoleon III was taken

prisoner in September,

whereupon a republic was

immediately proclaimed in

Paris. The siege of Paris

began. Bismarck exploited

the victorious campaign to

persuade the princes of

southern Germany to

acknowledge the King of

Prussia as German Emperor.

The proclamation of German

unity under Emperor Wilhelm

I was made in the palace of

Versailles on 18 January

1871. Shortly afterwards

Paris fell. The formal

declaration of peace was

signed in Frankfurt am Main

on 10 May 1871.

These bare dates and facts

about the Franco-Prussian

War have been given to

demonstrate just how closely

the composition of Triumphlied

was connected with the

course of political events.

Brahms was caught up by the

huge swell of patriotism. He

began work on his “Song of

Triumph” in October 1870 and

when, early in 1871, Wilhelm

I had been crowned Emperor,

Bismarck appointed Imperial

Chancellor and the German

Empire not only unified but

also slightly enlarged,

Brahms dedicated the work,

on completion, to Emperor

Wilhelm, signing the letter

in which he sought

permission to make the

dedication “Your Imperial

and Royal Majesty’s most

humble subject, Johannes

Brahms”.

Brahms knew his Bible and

had no difficulty in finding

the text appropriate to the

occasion: passages from

Revelation which were

general enough in their

wording to be taken out of

context, while encouraging

anyone who felt so inclined

to relate them - in a broad

sense - to recent events. A

line like “hat das Reich

eingenommen” could be, and

was intended to be,

associated with the

establishment of the new

empire, and if the line “Ein

König aller Könige, und ein

Herr aller Herren” was

applied to Emperor Wilhelm,

no one protested.

Patriotism commonly has a

reverse face as well: Brahms

was also giving voice -

covertly - to his dislike of

the French and of ‘sinful’

Paris. Revelation 19: 2

runs: “For true and

righteous are his judgments:

for he hath judged the great

whore, which did corrupt the

earth with her fornications,

and hath avenged the blood

of his servants at her

hand.” In the opening

movement of Triumphlied

the chorus sings the phrase

“For true and righteous are

his judgments” and then

falls silent for four bars,

leaving to the orchestra the

phrase that follows in the

Bible, the unpronounceable -

but fully understood - text

“for he hath judged the

great whore”. In Brahms’s

own manuscript copy of the

full score these words are

actually written in, in his

own hand, underneath the

orchestral part.

Though the circumstances

that gave rise to Triumphlied

cannot be reconstructed in

the consciousness of modern

audiences, it is still

possible to assess and

admire this monumental work,

written in a resplendent D

major, as an imposing

document of a historical

phenomenon.

NÄNIE

“Naenia” was

the ritual funeral song of

ancient Rome. Schiller gave

his “Nänie” the form of an

elegy in distichs made up of

regularly alternating

hexameters and pentameters,

but the content has more the

nature of a hymn than an

elegy, and the poem ends

with the expression of

homage to art, whose role it

is not only to console the

bereaved but also to ensure

life beyond death. The

transience of beauty and

perfection is illustrated by

the stories of three great

mortals, Euridice, Adonis

and Achilles; the latter

was, however, glorified by

the song raised in mourning

for him (“Aber die Klage

hebt an um den

verherrlichten Sohn” is the

poem’s turning point). Death

is irreversible, but to

become a song of mourning in

the mouth of those one has

loved (“ein Klaglied zu sein

im Mund der Geliebten”)

means a subsuming of death

in the ideal existence of

art.

The structure of Brahms’s

setting is governed by the

inner articulation of the

poem. While the first four

distichs are uniform in

tempo (Andante), time

signature (6/4) and key (D

major), with the fifth these

parameters change to Più

sostenuto - 4/4 - F sharp

major. The last distich

introduces a reprise, which

appears at first to

underline a

correspondence-by-antithesis

between the first and last

distichs; but then the last

hexameter “Auch ein Klaglied

zu sein im Mund der

Geliebten, ist herrlich”

brings a fitting conclusion

to the subject and the tone

of Nänie.

Brahms wrote the work in

1880-81 in memory of the

artist Anselm Feuerbach, and

dedicated it to his mother

Henriette Feuerbach; he

could have sung no more

beautiful or sublime song

for his friend.

GESANG DER

PARZEN (SONG or THE FATES)

Brahms’s last

major choral work presents a

number of riddles and

problems of interpretation,

arising from the

contradictions in the

relationship of the text and

the music. In this respect

Gesang der Parzen

makes a pair with Schickesalslied.

In the case of the Hölderlin

setting it is possible to

show that Brahms

deliberately used the medium

of the music to extend the

poem’s content, and even to

divert it in a direction

quite different from that

intended by the poet. There

is a strong case for arguing

that the composer felt a

similar lack of sympathy

with the content of Gesang

der Parzerz.

The song of the Parcae, the

Greek Fates, comes from

Goethe’s play Iphigenie

auf Tauris and

concerns the omnipotence of

the gods who can raise and

cast down human beings at

will - "wie’s ihnen

gefällt". Fear and impotence

are the human lot; children

and childrenßs children are

condemned along with their

fathers. After the five

stanzas of the actual song

of the Fates Goethe adds a

kind of epilogue in the same

metre: “So sangen die

Parzen; / Es horcht der

Verbannte / In nächtlichen

Höhlen, / Der Alte, die

Lieder, / Denkt Kinder und

Enkel / Und schüttelt das

Haupt.” This enigmatic

“epilogue” may have seemed

to Brahms like a hint from

the poet to look for some

foothold beyond the dismal

message of the Fates; he

probably identified himself

with the figure of the old

man shaking his head over a

world where the gods condemn

“children and

grandchildren”.

This provides us with a clue

to the interpretation of the

puzzling way in which Brahms

sets the fifth stanza, the

last of the actual song of

the Fates, in D major, 3/4,

marked “sehr 'weich und

gebunden” (“gentle and

legato”) and “dolcissimo”.

There is no metrical or

other structural difference

in the poem to correspond to

the musical isolation of

this stanza from the others.

The distinction is

underlined by the way Brahms

takes it upon himself to

repeat the first stanza

before the introduction of

the D major music: by this

means he draws a line, so to

speak, beneath the detailed

account of the terrors

pronounced by the Fates on

the one hand, but on the

other hand, by reiteration,

he emphasizes the

omnipotence of the gods.

From this point onwards the

composer’s interpretation

diverges from the substance

of his text. The setting of

the first four stanzas was

very straightforward, but

now the music is made the

means of registering

dissent. The discrepancy

between the lhounding of

whole generations described

in the text and the lovely,

lulling character of the

music is so obvious that the

purpose of the setting must

be to express rejection of

the idea contained in the

words. We might speak of a

contrast in simultaneity,

borne upon two differing

ideas and conceptions which

are communicated by language

on the one hand and by music

on the other: and those

contrasting ideas are the

ancient world’s concept of

fate and the Christian

concept of redemption.

In 1896 Brahms had this to

say about his setting of the

fifth stanza to Gustav

Ophüls, who published a

collection of the texts of

his songs: “I often hear

people waxing philosophical

about the fifth verse of the

‘Parzenlied’ [“Es wenden die

Herrscher”]. In my opinion,

the mere onset of the major

mode will melt the heart and

bring a tear to the eye of

the unsuspecting listener;

only at that point will he

be seized by a sense of all

the misery of mankind.” From

this we can deduce that

Brahms used the major mode

for a quasi-cathartic

purpose, so that

simultaneously with despair,

Christian faith in the

redemption of mankind finds

expression in an almost

imperceptible manner. The

composer of A German

Requiem and Four

Serious Songs was able

to tackle ontological

subjects such as that of Gesang

der Parzen from the

standpoint of a totally

undogmatic but nonetheless

Christian faith. The music

was carefully composed to

create the discrepancy

between it and the text - a

discrepancy which is the

true motive for the

composiuoni.

Peter

Petersen

(Translation:

Marz

Whittall)

|

|

|