|

|

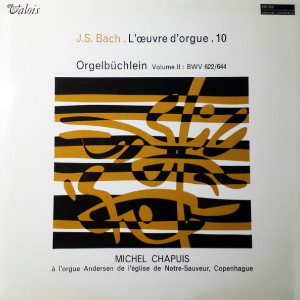

2 LP's

- BC 25107-T/1-2 - (p) 1969

|

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 849 - (p) 1968 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 850 - (p) 1968 |

|

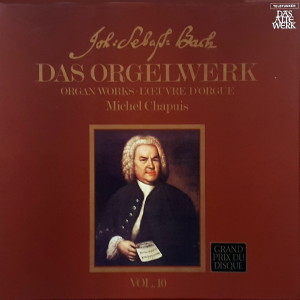

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) - Das

Orgelbüchlein |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 849) |

|

|

| Nun komm' der

Heiden Heiland, BWV 599 |

0' 52" |

|

| Gottes Sohn ist

kommen, BWV 600 |

0' 53" |

|

| Herr

Christ, der ein'ge Gottes Sohn, oder:

Herr Gott, nun sei gepreiset,

BWV 601 |

1' 38" |

|

| Lob

sei dem allmächtigen Gott, BWV

602 |

0' 48" |

|

| Puer

matus in Bethlehem, BWV 603 |

0' 47" |

|

| Gelobet

seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 604 |

1' 01" |

|

| Der

Tag, des ist so Freudenreich,

BWV 605 |

1' 33" |

|

| Vom

Himmel hoch, da komm' ich her,

BWV 606 |

0' 39" |

|

| Vom

Himmel kam der Engel Schar,

BWV 607 |

1' 00" |

|

| In

dulci jubilo, BWV 608 |

1' 25" |

|

| Lobt

Gott, ihr Christen allzugleich,

BWV 609 |

0' 43" |

|

| Jesu,

meine Freude, BWV 610 |

2' 18" |

|

| Christum

wir sollen loben schon, BWV 611 |

1' 43" |

|

| Wir

Christenleut', BWV 612 |

1' 08" |

|

|

|

|

| Helft

mir Gottes Güte preisen, BWV 613 |

1' 01" |

|

| Das

alte Jahr vergangen ist, BWV 614 |

2' 03" |

|

| In

dir ist Freude, BWV 615 |

2' 33" |

|

| Mit

Fried' und Freud' ich fahr' dahin,

BWV 616 |

2' 09" |

|

| Herr

Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf,

BWV 617 |

2' 11" |

|

| O

Lamm Gottes, unschuldig, BWV 618 |

3' 08" |

|

| Christe,

du Lamm Gottes, BWV 619 |

1' 05" |

|

| Christus,

der uns selig macht, BWV 620 |

1' 56" |

|

| Da

Jesus an dem Kreuze stund',

BWV 621 |

1' 10" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 850)

|

|

|

| O

Mensch bewein dein Sünde groß,

BWV 622 |

4' 34" |

|

| Wir

danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, daß

du für uns gestorben bist,

BWV 623 |

0' 53" |

|

| Hilf

Gott, daß mir's gelinge,

BWV 624 |

1' 19" |

|

| Christ

lag in Todesbanden, BWV

625 |

1' 25" |

|

| Jesus

Christus, unser Heiland,

BWV 626 |

0' 39" |

|

| Christ

ist erstanden (3 Verse),

BWV 627 |

4' 05" |

|

| Erstanden

ist der heil'ge Christ,

BWV 628 |

0' 40" |

|

| Erstanden

ist der herrliche Tag,

BWV 629 |

0' 51" |

|

| Heut

triumphieret Gottes Sohn,

BWV 630 |

1' 16" |

|

| Komm,

Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist,

BWV 631 |

0' 44" |

|

|

|

|

| Herr

Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend',

BWV 632 |

1' 12" |

|

| Liebster

Jesu, wir sind hier,

BWV 633 |

3' 26" |

| |

| Liebster

Jesu, wir sind hier,

BWV 634 |

| |

| Dies

sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot,

BWV 635 |

1' 19" |

|

| Vater

unser im Himmelreich, BWV 636 |

1' 29" |

|

| Durch

Adam's Fall ist ganz verderbt,

BWV 637 |

1' 20" |

|

| Es

ist das Heil uns kommen her,

BWV 638 |

1' 01" |

|

| Ich

ruf' zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,

BWV 639 |

2' 12" |

|

| In

dich hab' ich gehoffet, Herr,

BWV 640 |

0' 58" |

|

| Wenn

wir in höchsten Nöten sein,

BWV 641 |

1' 56" |

|

| Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt walten,

BWV 642 |

1' 25" |

|

| Alle

Menschen müssen sterben, BWV 643 |

1' 07" |

|

| Ach

wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig,

BWV 644 |

0' 35" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

| an

der Andersen-Orgel

der Erlöser-Kirche,

Kopenhagen |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kopenhagen

(Danimarca) - settembre 1968 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 849 · Vol. 9 - (1 LP) -

durata 33' 44" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 850 ·

Vol. 10 - (1 LP) - durata 34'

26" - (p) 1968 - Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25107-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 33' 44" / 34' 26" - (p)

1969 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

The “Orgelbüchlein”

(Little Organ Book) has for

decades been regarded as the

basic instruction manual of

the organist, while for many

music enthusiasts it is

altogether the climax of

Bach’s art of the organ, the

“Lexicon of Bach’s tonal

language”, to use the phrase

coined by Albert Schweitzer.

The first, the instructional

value, has remained

undisputed to the present

day. The second is a

definite exaggeration which

is more inclined to obscure

than clarify the view for

the singularity of these

works. The works are 45

short, i. e., concise chorale

arrangements without

interludes, musical

miniatures the length of a

single chorale

verse. There is thus no

possibility of expansion.

Within these bounds

the concertato style of the

Italians, with which Bach

happened to be preoccupied

at the time these pieces

were composed, is scarcely

capable of development.

Similarly there is little

scope here for the

compulsory modulatory scheme

which distinguishes Bach’s

free organ works; for the course

of the harmony is

essentially predetermined by

the chorale

melody. Therefore the entire

compositional imagination is

concentrated on enlivening

the short chorale

melodies in ever fresh

figural ways, and enriching

and interpreting them by

means of counterpoint and

harmony. This restriction

makes concentration

compulsory. The result is

the emergence of small works

of art whose luminosity and

forcefulness can hardly be

surpassed. However, as is

the rule with miniatures,

they are more closely

related to pure

craftsmanship than to

larger, more extensive

creations.

The craftsmanship-systematic

trait is even more evident

in the original plan of the

overall collection. For the

“Orgelbüchlein”

is a torso. In the thick

volume of music, which we

still possess today, Bach

had initially entered at the

top of the individual pages

which were intended to

accommodate the compositions

the titles of the chorales:

a total of 163 pieces. In

this respect he accorded

with the system usual at

that time in the Lutheran

hymn-books,

which begins with the feasts

of the church year from

Advent to Trinity and

carries on to the catechism

hymns and the hymns for

special occasions. His

selection was evidently made

according to an old Weimar

hymn-book. When setting out

his little organ book he

immediately took into

account the varying volume

of the planned arrangements:

for most of them he reserves

one page of manuscript, for

some longer ones two pages,

and he also arranges the

longer ones in such a way

that the performer does not

need to turn the page during

the piece.

However, of the envisaged

Chorales he then set out

only 45, just a little more

than a quarter. The hymns

from Advent to Eastertide

are almost entirely set to

music. Then the gaps become

even wider: from many of the

groups he had in mind he

composed only one hymn, from

various others, such as

church hymns or from the

daily and grace group of

songs, he composed none at

all.

The chorales

listed are intended for the

following feasts and

occasions: Advent BWV

599-602, Christmas 603-612,

New Year 613-615, Candlemas

616-617, Passion 618-624,

Easter 625-629, Ascension

630, Whitsun 631,

Introductory Hymns 632 to

633/634, Catechism Hymns

635-636, Repentance 637,

Justification 638, Christian

Change 639, Consolation

640-642, Funeral 643,

Repentance and Holy

Communion (supplement) 644.

Except for very few

subsequent supplementations,

all of these pieces were

composed in Weimar between

1713 and 1715 and entered in

the Orgelbüchlein.

(It is only a legend that

the Orgelbüchlein

was produced in order to

instruct the older sons at

the end of the Köthen

years or even that it was

used as a“pastime” during

the Weimar confinement at

the end of 1717). Quite

evidently it was intended to

be a complete collection of

those chorales

which Bach had to play in

his position as court

organist during church

services: a complete chorale

book for the organist -

however, not for

accompanying the

congregation’s singing, but

conceived for soloist

performance. It is closely

connected with Bach’s Weimar

official duties, and thus

its torso-like condition can

initially be explained by

the fact with his

appointment as concertmaster

in the spring of 1714 Bach

regularly had to compose cantatas

and the organ works had to

recede into the background.

His interest in these small

forms may have subsequently

waned: the 45 listed pieces

provided sufficient examples

for the various

contrapuntal, figural and

harmonic possibilities in

which a chorale

was to be arranged.

Therefore he subsequently

gave the uncompleted Büchlein

at the end of his Köthen

years a title which

emphasises the educational,

exemplary intention of the

individual pieces and no

longer refers to the

hymn-book type arrangement

intent upon perfection:

“Orgel-Büchlein

in which a beginning

organist is instructed how

to set a chorale in

diverse manners, also how

to qualify in study of the

pedal, in so far as the

chorales contained herein

shall be played with the

pedal fully obbligato

To God on

High all honour due.

To teach

another skills anew.”

Thus the

pieces are now seen as

examples of how to set a

chorale and obtain

proficiency in using the

pedal.

The 45 pieces (if one counts

separately each of the two

only slightly differing

versions of “Liebster Jesu”

BWV 633 and 634 there are

46) are almost all in

four-part settings. Only two

(619 and 633/634) are

five-part, two (599 and 615)

in some passages expand the

four-part setting to

five-part. The chorale

melody is mainly in the

treble, only in 611 it is in

the alto, and in the canonic

setting 618 in the pedal and

alto. As a rule it is

rendered in simple note

values or figured to only a

minor degree in a somewhat

expanded chorale measure.

The precise tempo emerges

from the movement style and

the density of the other

parts. Only in two cases

(627 and 635) is the chorale

scored as broadly expansive

in long note values.

Expression marks such as

largo, adagio or adagio

assai (622) at the same time

indicate particularly

intensive expression in some

settings, but are absent in

other similar ones.

Similarly performance and

registration directions

exist in the case of only a

few of the settings, and are

by no means as

systematically provided as

the present-day organist

would wish. This is why

various interpretations,

especially of the Orgelbüchlein,

differ to the extent of

complete contradiction, and

even of unrecognizability.

In a few settings the main

expression has been shifted

to the chorale part itself,

which for this purpose is

strongly figured. The best

examples for this technique

are the two Passion or

funeral Chorales “O Mensch,

bewein dein Sünden

gross” (622) and “Wenn wir

in höchsten

Noten sein” (641). In eight

pieces the chorale melody is

arranged as a canon, thus

all the more strongly

incorporating the other

voices: 600, 608, 620, 629

octave canon between discant

and pedal; 618 fifth canon

between pedal and alto; 619

canon in the interval of the

twelfth between manual bass

and discant, 624 and 633/634

fifth canon between discant

and alto.

If one excludes those

settings in which the pedal

performs the chorale as one

of the two canon voices, it

is conspicuous that in the

whole of the Orgelbüchlein

that manner of setting which

was once particularly usual

is missing in which the

chorale is played only by

the pedal - with a

distinguishing register in

discant, alto or tenor range

- and the manuals were

reserved for the

accompanying voices. Perhaps

this is connected with

Bach’s intention to use the

pedal obbligato, that is to

say in this context

independently both as

regards the chorale melody,

as well as a really

independent bass part, and

not merely as a

reinforcement of the bass.

In this way the most

important counter-part to

the chorale cantus firmus is

transferred to the pedal.

Its form depends not only

upon the chorale melody, but

above all upon the

arrangement principle which

Bach chose for the

individual piece, and upon

the task which he apportions

to the individual voices.

The basic rule in this

respect is that the

arrangement principle, once

chosen, is maintained for

the whole piece: uniformity

of the mode of arrangement.

A firmly marked motif, often

also only a pithy rhythm (as

for example in 629 of the

anapaest), determines the

contrapuntal voices and is

developed in them. It can be

taken from the chorale

melody (as for instance in

613, 614, 635 and 641), or

be freely invented. Longer,

clearly contoured motifs are

mainly arranged imitatively.

The possibility now results

of clearly distinguishing

the individual voices from

each other in the movement

(and then also mainly in the

motif element). For example

in the threepart “Ich ruf’

zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ”

(639), where, with the

crotchet basic movement of

the chorale, the pedal bass

is played in quavers and the

tenor in semiquavers. The

various motional forms of

individual voices in 600,

607, 617 and 624 are

maintained in a similarly

strict manner. More

frequently the two middle

voices combine into an

independent duet vis-a-vis

the discant and the pedal

bass, as for instance in

603, 604 or, particularly

clearly, in 605, as well as

in numerous other settings.

The motion of the duet often

alternates with that of the

pedal (602, 642, 643) or

extends to the discant (e.

g. 606). This duet-style

lead of the middle voices is

mainly due to a particularly

independent ostinato pedal

rendering (603, 604, 628,

637 and 644); as a steadily

binding element it has to

mediate between the ostinato

bass and the chorale

discant. The middle voices

also form into a duet where

they are flanked by two

canon parts. In the setting

of the Christmas carol “In

dulci jubilo” (608) they

unite into a second canon

which counterpoints the

rocking 3/2 rhythm of the

cantus firmus voices in 9/8

movement.

However, the three lower

voices are just as often

treated as a uniform complex

from the point of view of

motif and rhythm. In this

respect they usually

supplement each other to

form a consecutive

semiquaver movement. This is

the case with the very first

piece, the Advent hymn “Nun

komm’ der Heiden Heiland”.

In this style of setting too

the pedal maintains its role

as the main counter-part to

the chorale cantus firmus,

but on the whole the setting

is uniformly through formed.

The examples of where the

motif material of the

accompanying parts is taken

from the chorale-usually

from its first line - or in

which a significant motif is

imitatively arranged, for

the greater part belong to

this group.

However

much the individual settings

might differ from each

other, they nevertheless all

keep to the self-chosen

restriction of performing

the chorale melody only

once, and that in one

passage without interlude.

The only deviation from this

is the arrangement 615 “In

dir ist Freude”, the setting

to the old dance melody by

Gastoldi, which shortly

after its composition was

parodied in sacred form.

This piece is more of a

chorale paraphrase than a

strict organ chorale.

The chorale melody retains

its text also in the case of

instrumental performance. It

is known to the

congregation, which hears

the words so to speak in

spirit. To what extent did

Bach when choosing his

arrangement technique allow

himself to be guided by the

text, and how strongly has

he interpreted this text

literally? Despite all the

preoccupation with the

musical-rhetorical figures

and the musical symbolism of

Bach’s era, only very

general statements can be

made here which are far from

well-founded in every

respect. For this reason one

should be careful of

precipitate interpretations,

especially as regards

word-tone connections. The

fact that two of the

arrangements (600, 601) are

expressly intended to be

used for two different hymn

texts each, and further the

idea of which chorale verse

initially inspired Bach,

should of itself provide

grounds for caution.

That the overall emotion of

the text also always

determines the character of

the arrangement is evident

from the first comparison,

such as the joyful Christmas

Chorales with the passion

hymns. But why of all things

the artistic chorale for the

New Year “Das alte Jahr

vergangen ist” (614) should

be even more chromatic and

more suffering in expression

than the former cannot be

explained solely from the

chorale text. That the

ostinato seventh descents of

the pedal in the repentance

hymn “Durch Adams Fall ist

ganz verderbt” (637) are

intended to illustrate the

fall of man is wholly

convincing; the continual

alterations in this setting

might also with some

justification be accepted as

the musical symbol of

“corruption”. But the sign

of the cross figure to which

reference is constantly

made, especially in

connection with 621, “Da

Jesus an dem Kreuze stund”,

is far too common from a

musical point of view for it

to be accepted as a metaphor

for the cross and suffering

without further indications

to support this

interpretation: it is seldom

lacking in any piece of

music. In this respect it

should be borne in mind that

even during the Baroque

period it was certainly not

a part of the nature of

musical works of art to

provide outward visible

expression to all textual

and conceptual references

which may have been in the

composer’s mind, and that

music, as the language of

the soul, possesses rather

its own immediately

comprehensible terms which

cannot be translated.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

This critical

and complete stylistic

survey of Bach's

organ works is

the tenth

and

last part.

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|