|

|

2 LP's

- BC 25104-T/1-2 - (p) 1967

|

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 843 - (p) 1967 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 844 - (p) 1967 |

|

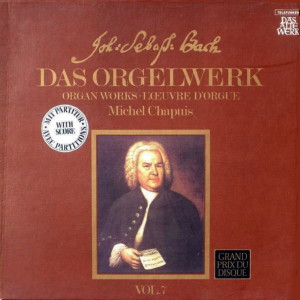

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 843) |

|

|

| Toccata (Toccata

und Fuge) d-moll, BWV 565 |

7' 50" |

|

| Fuge c-moll über

ein Thema von Giovanni Legrenzi,

BWV 574 |

6' 10" |

|

| Toccata

E-dur, BWV 566 (Präludium

und Fuge) |

9' 15" |

|

|

|

|

| Toccata

(Toccata, Adagio und Fuge) C-dur,

BWV 564 |

13' 03" |

|

| Trio

d-moll, BWV 583 |

4' 05" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge a-moll, BWV 551 |

5' 08" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 844)

|

|

|

| Passacaglia

c-moll, BWV 582 |

12' 28" |

|

| Fuge

h-moll über ein Thema von Corelli,

BWV 579 |

3' 51" |

|

| Canzona

d-moll, BWV 588 |

5' 03" |

|

|

|

|

| Fantasie

G-dur, BWV 572 |

8' 16" |

|

| Allabreve

D-dur, BWV 589 |

3' 12" |

|

| Pastorale

F-dur, BWV 590 |

11' 21" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

an

der Andersen-Orgel der

Erlöser-Kirche, Kopenhagen

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kopenhagen

(Danimarca) - febbraio 1967 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 843 · Vol. 3 - (1 LP) -

durata 46' 13" - (p) 1967 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 844 · Vol. 4 - (1

LP) - durata 40' 23" - (p) 1967 -

Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25104-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 46' 13" / 40' 23" - (p)

1967 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Bach’s mode of

composition displays from

the outset a tendency

towards the great and the

diverse. Despite the

narrowness and provinciality

of the conditions under

which he had to work, his

artistry is cosmopolitan in

outlook. Any attempt to

adapt himself to his musical

environment or to restrict

himself to simplicity and

modesty was alien to him.

This also accords with the

inclination to try out the

various genres, forms and

styles from the most varied

aspects in a systematic

manner, never forgoing any

impetus but always searching

for his own more appropriate

solution. In this respect

there is the combination of

a thirst for knowledge,

pride in craftsmanship and

speculative talent, as well

as the delight - already

evident in his youth - in

seeing compositional tasks

as parallel exercises of the

intellect.

The early piano and organ

works provide especially

abundant illustrative

material of the wealth of

forms in which he

experimented, which he

further developed or which,

after trying out,

disregarded altogether. The

present album contains

compositions of the most

diverse kinds, giving

wide-ranging examples of the

strictly imitative and the

toccata-like prelude styles

of movement and their

connection with the

complete, multipart work. In

addition there is the

ostinato form of the

passacaglia, the aria form

of the trio and the

sonata-style movement

sequence of the pastoral.

The formal and stylistic

diversity is already

expressed in the various

titles of the works. In some

cases they are genre titles

which at the same time

indicate style and formal

arrangement (toccata,

prelude, fugue, canzona,

passacaglia, fantasia). In

other instances they give

(as in “trio”) only the type

of movement and sometimes

the stylistic tradition

(alla breve) or also the

designation and melodic type

(pastoral). Except for the

Trio and the Pastoral, and

perhaps also the G major

Fantasia, they are youthful

works or compositions from

the nascent mastery of the

early Weimar years. It is at

first difficult to accept

the fact that even the

famous D minor Toccata and

the grand Passacaglia are

also part of these early

works. However, the sources

from which these pieces have

been handed down, clearly

indicate this period. The

early works fascinate us

because of the impetuous

power of their themes, the

bold flourishes, the manner

which often extends to sheer

high spirits, with which the

virtuoso performer was able

to display his brilliance by

way of his instrument. As

yet the thoughtful

contrapuntal combination,

the polyphonic independence

of the parts, the harmonic

richness are missing, and

the art of letting the

musical form grow of itself

from the possibilities of

the theme is only slowly

developed. The form is still

more impelled by powerful

flourishes than built up on

the foundations of inner

musical media. Thus the

problem of the musical

cohesion in the early works

is resolved for the first

time where such cohesion is

already laid down by the

compositional genre: in the

chorale arrangements and the

themes above an ostinato

repeated bass, as here in

the C minor Passacaglia.

Toccata and Fugue D

minor, BWV 565

The old toccata form with

its frequent alternation of

figurative and fuguing

sections is reduced here to

a clear three-part style: a

broadly structured fugue is

encompassed in figurative

sections. The introductory

first section is almost

incomparable in its

compelling temperament. It

has the effect of an orator

who, with his very first

words, intends to hold the

audience in his spell. Rapid

scalar passages with fermata

conclusion, ascending and

descending figures leading

to fully stopped blocks of

chords, alternating play of

the hands, the emphatic

application of the pedal:

these trusted and tried

elements of the free toccata

theme are welded into an

irresistible prelude which

exploits in a concise way

the tension of the dominant

harmony. The toccata spirit

also lives in the marked

homophonically arranged

fugue with its long

interludes and its thematic

announcement at the

beginning of the

introductory passage. The

final part reverts to the

figurative and chordal

themes of the beginning and

intensifies them.

Fugue in C minor on a

Theme by Legrenzi, BWV 574

Even before he had become

acquainted with the Italian

solo concerto, Bach had

studied the trio sonatas of

the great Italian violinists

and learned from their

song-like instrumental

style. His fugues on themes

by Corelli, Albinoni and

Legrenzi testify to this

fruitful preoccupation. He

recognized at once how he

could profit from the

plastic themes of the fugued

allegro movements for his

own art and, going beyond

the examples, showed how the

possibility inherent in the

themes could be presented in

a complete movement. He

changed the al fresco of the

Italians into well

constructed architecture. In

the present work, the

original pattern of which

has evidently been lost, he

formed from the adopted main

theme and a second one,

which from the beginning was

probably initially

counterpointed in the

original, a three-part

double fugue which runs into

a figurative coda. Both

themes are exposed in turn

and only brought together in

the third part. Two earlier

versions (BWV 574a and b) -

the first still without the

coda - show how seriously

Bach devoted himself to the

work on this fugue.

Prelude (Toccata) and

Fugue E major, BWV 566

The first fugue follows a

prelude which begins

figuratively and concludes

with a tightly textured

section. It is based on an

unusually long, almost

clumsy theme which, however,

in the contrapuntal

arrangement immediately

loses its awkward shape and

proves to be particularly

productive. The second

fugue, which follows after a

brief connecting passage,

forms the beginning of this

theme in three-part metre

and in the transition leads

from contemplative calm to

concerto-like thrilling

mobility into the homophonic

coda. Thus in this work the

toccata-style construction

merges with the variation

principle of the canzona.

Toccata C major, BWV 564

In this work the tendency to

adapt in the toccata the

original free alternation of

figurative and fugued

sections into a sequence of

intrinsically complete

movements reaches a climax.

The second movement, which

thematically emerges from

the introductory figuration,

resembles a concerto allegro

constructed on the contrast

between an ascending scalar

figure and a descending

triad motif. The third

movement is a copy of a solo

concerto adagio. Accordingly

the framework, the

figurative prelude and

particularly the concluding

fugue, is extended.

Subsequently Bach did not

further develop this

multi-theme arrangement. The

coupled movement prelude

(toccata) and fugue provided

greater possibilities for

his mode of composition

which oriented towards

concentration.

The Trio in D minor, BWV

583, belongs as

regards style and period to

the great trio sonatas of

the 1720’s

(see Organ Works, I) and

could be the centre movement

in one of these works

constructed in concerto

style. With the

non-schematic manner in

which the various imitation

sections are developed from

each other, repeated and in

the centre part augmented by

an eloquent counter motif,

it virtually amounts to a

model of a free da capo

form.

As regards the Prelude

and Fugue A minor, BWV

551, this is in shape

more of a five-part

toccata: two fugues, in

second and fourth place, are

framed and combined with

toccata-like sections. The

first fugal theme is

developed from the

semi-quaver movement of the

introductory part; the

second is linked, by way of

the firm counterpoint which

it immediately takes on,

with the first. The short

piece is one of Bach’s

earliest compositions to

have come down to us.

Although in many respects

incomplete, it nevertheless

makes a powerful impression

and provides a first notion

of the master who was to

come.

Passacaglia C minor, BWV

582

Passacaglia and

chaconne, series of

variations deriving from the

dance, in slow three-four

time above an unchanging

ostinato repeated bass

theme, were at their height

in the instrumental music of

the outgoing 17th century.

When Bach became involved in

them they were already out

of fashion. However, it is

doubtful if this is the

reason why he did not go

beyond this one organ

passacaglia and the sole

violin chaconne. It is

perhaps more likely that he

had also completely

exhausted the possibilities

of this form in the two

contrary and incomparably

magnificent works. Instead

of the usual four bar, Bach

uses in the organ

passacaglia an eight-bar

theme which he achieves by

extending a four-bar

passacaglia bass by André

Raison. In 21 periods of

eight bars each he builds up

the work above the

unchanging theme and lets it

fade away in only a slightly

shorter fugue on this theme.

His mastery is particularly

evident in the interlacing

of the individual periods,

their combination into

larger units, in the art of

not letting the flow break

off but continuing it in a

compelling and tension-laden

manner. The principle of the

rhythmic-figurative

variation progressing from

period to period is

subordinated to the law of

greater cohesion, as already

apparent for instance in the

melodic summary of the 2nd

and 3rd period, or even more

clearly in the 12th period.

Precisely where the theme is

transferred from the pedal

bass to the discant, the

figuration modus of the

preceding section is

maintained. This following

on process creates the

precondition for the broadly

conceived final augmentation

which begins with the 17th

period, just where the theme

- descending by way of alto,

tenor and manual bass - has

once more returned to the

pedal. The crowning final

fugue uses only the four-bar

main subject, which proceeds

in alternating crotchets and

minims, and links it up with

a countersubject in quaver

movement and a second in

semi-quavers.

Fugue in B minor on a

Theme by Corelli, BWV 579

The basis is a 39-bar

long fugato from the Trio

Sonata op. III, No. 4 by

Corelli published in 1689.

The theme and counter-theme

are set out there, and the

possibility of stretto is

also already utilized. In

Bach’s hands this “material”

exposed for three parts

changes into a four-part

fugue extending to 102 bars

with several expositions and

long episodes. The larger

scale arrangement cannot,

however, disguise the fact

that when transferred to the

organ the character of the

themes has also changed.

Their electrifying verve

comes more into its own in

the al fresco of the violin

fugato than in the carefully

balanced architecture of the

fugue.

Canzona in D minor, BWV

588

The canzona, an instrumental

imitation of the French

chanson with its series of

imitative and homophonic

sections, effected as early

as 1600 the transition to

the fugue, namely with

restriction to a single

theme that was varied in

several sections. What

finally remained was

development of the theme

into an even bar and an

uneven bar section. This two

part form is also strictly

adhered to by Bach’s sole

work described in the title

as a “Canzona”, one of the

most mature testimonies from

Bach’s early period. The

confidently progressing long

theme is counterpointed with

the well-known chromatic

descending fourth.

Fantasia in G major, BWV

572

This work, unusual as

regards both construction

and content and described in

only very general terms by

the title “Fantasia”,

appears to be based on

French patterns. This is

also indicated by the French

movement descriptions. Two

figured movements, headed

“Très

vitement” and “Lentement”,

provide the framework for an

extended five-part

“Gravement” which in its

density (while renouncing

imitation) and persistent

intensity based upon

suspended harmony (waiving

formal cuts or rhythmic

alternation) has

scarcely anything to compare

with it. However,

the“fantastic” urgency,

apparently directed towards

boundlessness, acquires a

firm hold by way of strict

control of the individual

parts and the bass

foundation which continually

binds the harmonic sequence

to a gradual, upward moving

tonal progression.

The Allabreve in D major,

BWV 589, is, as far as

the theme and manner of the

exposition are concerned,

related to the D minor

Canzona, except that the

exacting length is not

achieved by the change in

movement form, but by the

normal fugal construction

with long episodes. A major

contribution to the

overlapping cohesion is

provided by a quarter

movement no longer

interrupted as from the 6th

bar which is gained from the

4th bar of the theme. The

title “allabreve” indicates

the stylistic descent from

the ricercar with its

motet-like construction,

which avoids concerto-style

elements and - reverting to

the old vocal polyphony - is

scored in large note values

which have to be read “alla

breve”.

Pastorale in F major, BWV

590

Oboe melody above bourdon

notes, since the 16th

century the musical image of

the shepherd’s idyll, are

bound up in the church

pastoral with the rocking

rhythm of 6/8 or

12/8

beats; for this now refers

to the Christmas world of

the shepherds at the manger.

Bach’s organ pastoral was

most certainly composed for

the Christmas church

service. The main movement,

which builds up above long

sustained bourdon tones of

the pedal, is joined by

three manual movements, of

which the second, the slow

one, is in the minor key of

the upper fifth (C minor),

unusual in such sonata-style

sequences.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

This critical

and complete stylistic

survey of Bach's

organ works is

the seventh

part and

will be

continued by

further

releases.

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|