|

|

2 LP's

- BC 25102-T/1-2 - (p) 1970

|

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 859 - (p) 1970 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 860 - (p) 1970 |

|

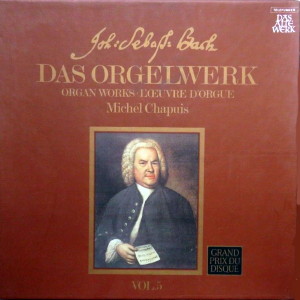

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 859) |

|

|

| Konzert a-moll,

BWV 593 - nach Vivaldi |

11' 19" |

|

| Konzert C-dur,

BWV 595 - nach Prinz Johann Ernst

von Sachsen-Weimar |

4' 20" |

|

| Konzert

d-moll, BWV 596 - nach Vivaldi |

10' 14" |

|

|

|

|

| Konzert

C-dur, BWV 594 - nach Vivaldi |

19' 34" |

|

| Konzert

G-dur, BWV 592 - nach Prinz

Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar |

6' 43" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 860)

|

|

|

| Präludium,

Trio und Fuge B-dur, BWV 545b |

10' 52" |

|

| O

Lamm Gottes, unschuldig |

4' 33" |

|

| Kleines

harmonisches Labyrinth C-dur,

BWV 591 |

4' 01" |

|

| Trio

G-dur, BWV 1027a |

3' 13" |

|

| Fantasie

C-dur, BWV 573 (unvollendet) |

1' 06" |

|

|

|

|

| An

Wasserflüssen, Babylon,

BWV 653b |

5' 46" |

|

| Ach

Gott, vom Himmel sieh' darein,

BWV 741 |

4' 08" |

|

| Trio

G-dur, BWV 586 - von

Telemann |

2' 00" |

|

| Aria

F-dur, BWV 587 - von

François Couperin |

3' 21" |

|

| Fantasie

c-moll (anonym) |

2' 35" |

|

| Fuga

G-dur, BWV 577 |

2' 08" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

| an

der Andersen-Orgel der

St. Benedikt-Kirche,

Ringsted/Dänemark |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Ringsted

(Danimarca) - agosto 1970 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 859 · Vol. 19 - (1 LP) -

durata 52' 10" - (p) 1970 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 860 · Vol. 20 - (1

LP) - durata 43' 43" - (p) 1970 -

Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25102-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 52' 10" / 43' 43" - (p)

1970 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

The present

album comprises Bach’s five

organ concertos based on

others’ instrumental

concertos, as well as a

series of miscellaneous

pieces, individual choral

arrangements, trios,

fantasias and fugues of

varying worth and in some

cases of disputed origin. It

thus provides a glance into

an aspect of Baroque organ

practice which as a rule

receives too little

attention when seen from the

usual point of view: the

daily organ practice with

which the organist extends

his repertoire and becomes

acquainted with the new

styles and those of others.

- The share of the arranger

in the new designing of

these works could be

extremely varied: from the

simple text book style

transcription to the

complete reorganization and

fresh creation on the basis

of the old material there

are all the stages of

appropriation. With such a

system of working the

question as to author also

becomes hazy. The old

manuscripts very often fail

to mention the composer of

the original work - he was

in any event known to the

initiated - and designate

the work by the name of the

arranger. Thus, among the

works ascribed to Bach, one

or the other will no doubt

turn out to be the

arrangement of another’s

piece. - The solo concerto

was eminently suitable for

such arrangements. The

Venetian violinist Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) had

within a few years developed

it into a leading

instrumental genre of the

time. The principle of

concerto playing, the

changing of different sound

groups, the contrast between

tutti and solo, had already

been customary for about 100

years at that time. In the

concerti grossi of Corelli

and the solo concertos of

Torelli certain forms of

several-part instrumental

concerto had already taken

shape before 1700. It was

left to Vivaldi, however, to

create the new concerto type

that held the future. On the

pattern of the Neapolitan

opera sinfonia he had

reduced the number of

movements to three: two fast

outer movements and a slow

middle movement which was

mostly of a lamento

character and in uneven

tempo. The most important

element, however, was its

formal, harmonious and

thematic disposition of the

fast concerto movement. The

starting point is the

several-part tutti

ritornello with a spirited

opening movement, a

continuation in sequence and

cadenced epilogue. This is

followed in frequent change

by figurative solo passages

and shorter tutti, made up

of fragments of the

ritornello. The movement

usually ends with a free

repetition of the entire

ritornello. The compactness

of the movement is

reinforced by a clear

harmonic disposition, in

which the main functions of

the major-minor tonality are

exploited to the full. The

solos modulate while the

tutti strengthen the

particular key. The thematic

pithiness and the thrilling

action of these movements

would be inconceivable

without the singilarly new,

sharply accentuated tempo

rhythm and the clearly

jointed dominant cadences.

Five Concertos based on

Various Masters (BWV

592-596) (a sixth, BWV

597, is only weakly

authenticated). Vivaldi’s

concertos became quickly

known in the German

residences and were

frequently copied. Bach had,

during his Weimar organist

and concertmaster period -

like his cousin Johann

Gottfried Walther who was

active there - transposed a

large number of such

concertos to the piano and

to the organ. The organ

inevitably was particularly

suitable for concerto

arrangements of this kind;

by way of alternation

between the swell-organ or

organo pleno and Rückpositiv,

the organist was capable in

perfect manner of depicting

the contrast among the

various concerto

instrumental groups, the

change from tutti and solo.

Bach’s aim with these

arrangements was to

transpose the original

composition as faithfully as

possible to the new

instrument. Here and there

he complemented a

counterpoint, enriched the

harmony and adapted the

figuration to the

performance technical

conditions of the organ. On

the whole, however, he

refrained from interference

with the score, and

apparently did his best to

produce no more than a

“keyboard excerpt” of the

original.

1) Concerto A minor based

on Vivaldi, BWV 593.

Vivaldis’ A minor concerto

for two violins and strings

op. 3, No. 8 (Estro

armonico), that is

transposed here, is one of

the outstanding pieces among

over 400 concertos composed

by the Venetian master. The

first movement in particular

fulfills all the demands

that were made upon a modern

concerto movement: a long,

several-part ritornello with

a spirited introductory

subject at the beginning,

richly alternating solo

passages which do not

content themselves with

figurations but develop

their own themes, a return

of the entire ritornello in

extended form at the

conclusion. The adagio in D

minor and in 3/4

time provides the expressive

contrast. It is constructed

above a bass figure which

introduces and concludes the

movement in ritornello

style, and quasi ostinato,

abridged in part, retains it

throughout the whole

movement. The final allegro,

which again is built up in

the concerto movement form,

also differs in character

and in tempo (3/4)

from the first allegro. The

ritornello is more

compressed, the solos are

more expansive.

2) Concerto C major based

on Johann Ernst von

Sachsen-Weimar, BWV 595.

The two music loving Weimar

princes, Ernst August and

Johann Ernst, were diligent

pupils of Johann Gottfried

Walther. The younger, Johann

Ernst, who died in 1715 at

the age of nineteen,

composed a series of solo

concertos on the Italian

pattern, some of which were

also published. Bach, who

was on friendly terms with

the gifted princes, arranged

some of the concertos for

the piano and organ. The

present organ arrangement

contains only the first

movement of a three-movement

concerto - although

considerably extended - the

other movements of which

have been handed down to us

solely in the piano

arrangement also by Bach,

BWV 984.

3) Concerto in D minor

based on Vivaldi, BWV 596.

This work, which is

available in a manuscript by

Johann Sebastian Bach, was

for a long time thought to

be a composition by his son

Wilhelm Friedemann. It was

only later discovered that

it was the arrangement of

the D minor Concerto No. 11

from Vivaldi’s op. 3; even

later it transpired that the

arrangement originated from

Johann Sebastian Bach

himself. Before the aged

Wilhelm Friedemann sold his

father’s manuscript he wrote

across the piece: “di W. F.

Bach, manu mei Patris

descriptum” (“by W. F. Bach,

copied by the hand of my

father”). It is difficult to

imagine what induced him to

carry out this forgery; for

the purchaser, Johann

Nikolaus Forkel, must have

been far more interested in

a work by Johann Sebastian

Bach than a composition by

his son. Judging by its

formal style, the work

accords more with the

concerto grosso of the

Corelli character than the

modern solo concerto. The

instrumentation of the

original, which confronts

the “grosso” with the

soloist “concertino”

consisting of two violins

and cello, points in this

direction.

4) Concerto C major based

on Vivaldi, BWV 594.

The organ arrangement is

evidently based upon an

earlier version of the

violin concerto D major

distributed in manuscript

form, published in 1717 as

No. 5 of the second

instalment of op. 7. The

recitative middle movement

was exchanged in the printed

version for another.

Compared to the A minor

concerto op. 3, No. 8

referred to above, the

dimensions have considerably

expanded, particularly of

the soloist sections, and

the virtuosity is greatly

enhanced. Departing from

custom, the first movement

waives the return of the

complete ritornello at the

conclusion, the last fading

out into a long solo cadenza

with which the end is

considerably protracted.

5) Concerto G major based

on Johann Ernst von

Sachsen-Weimar, BWV 592.

The three-movement work,

which Bach also arranged in

addition for harpsichord

(BWV 592 a), despite all its

playful mood, clearly

reveals the difference from

its Italian pattern. It

lacks the generously

proportioned design, the

strength of the themes, the

singing quality of the

figuration. Nor is it up to

the standard of the

one-movement concerto

fragment by the prince

reproduced above, and it is

of interest only as a trial

piece by a gifted young

dilettante to whom Bach felt

an obligation.

Miscellaneous Works

1) Prelude, Trio and

Fugue B-flat major, BWV

545 b. The prelude and

fugue are already contained

in the known and authentic

version in C major (BWV 545)

in the III series of Bach’s

Organ Works. The present

version and movement

sequence originates from an

English manuscript from the

second half of the 18th

century, and is ascribed

there to the organist at

London’s Westminster Abbey,

John Robinson (1682-1762).

It was published for the

first time in 1959. After

the prelude (BWV 545 a,

transposed to B-flat major)

there follows, linked by a

short adagio movement, an

organ version of the trio

movement, which was

previously known to us only

as the finale of the sonata

for viola da gamba and

harpsichord G minor (BWV

1029). A short tutti theme

connects up with the fugue

BWV 545/2, which here, like

the prelude, is transposed

into B-flat major. The two

bridging movements probably

originate from Robinson. It

is uncertain whether Bach at

one time envisaged the trio

in this context; some

manuscripts provide the

prelude and fugue BWV 545

together with the slow

movement of the organ sonata

BWV 528.

2) O Lamm Gottes,

unschuldig. This

double chorale arrangement

by Bach did not become known

until the 1950’s.

The first version proceeds

in imitative style. The

second paraphrases the

chorale melody in the manner

of the so-called “Arnstadter

congregational chorales”, as

described more fully in the

second series of the Bach

Organ Works.

3) Little harmonious

Labyrinth, BWV 591.

When, around 1700 the even

tempered pitch of keyboard

instruments began to assert

itself, pieces came into use

which modulated through the

entire circle of fifths, or

at least aimed at roving

around in the keys with the

aid of enharmonic

alternations. The present

piece, which is hardly

likely to have been composed

by Bach, but rather by the

Dresden chapel master Johann

David Heinichen (1683-1729),

arranged the harmonic puzzle

game in three sections: the

overture-style “Introitus”,

the “Centrum”, in which a

chromatic theme is

introduced as a fugue, and

the slow “Exitus”.

4) Trio G major, BWV

1027a. The work, which

has been handed down in only

a single copy which gives

little cause for confidence,

consists of a short,

musically not very

convincing version of the

last movement of the sonata

for viola da gamba and

harpsichord BWV 1027 or of

the musically identically

sonata for two flutes and

continuo BWV 1039. As Ulrich

Siegele has shown, by and

large it is closer to the

flute version. Up to the

present day it has not been

clarified whether it is an

unskilful, non-authentic

arrangement of this version,

or a spoilt descendant of an

“original version” to which

the two sonata movements go

back.

5) Fantasia C major, BWV

573. Bach entered this

five-part fantasia, which

from its beginnings was to

be a large-scale work, in

the first piano book of his

wife Anna Magdalena in 1722.

Unfortunately it was not

completed. It breaks off bar

13 with the cadence at the

3rd degree.

6) An Wasserflüssen

Babylon, BWV 653 b.

Unlike the wellknown

four-part arrangement of

this chorale melody from the

“Eighteen Chorales” of the

later Leipzig period, this

five-part original version

is usually neglected. It is

scored throughout for double

pedal - and perhaps this

performance technique

speciality, which went out

of use among organists in

the first half of the 18th

century, was the reason for

the subsequent

rearrangement. This earlier

version

is certainly not inferior to

the later one as regards

beauty and stylistic art.

The heartpiece of the

movement is the second part

which repeats a plaintive

eight-bar melody formed from

the first two chorale lines

going through the entire

piece quasi ostinato.

7) Ach Gott, vom Himmel

sich darein, BWV 741.

This chorale arrangement by

the young Bach is marked by

tempestuous strength and

wealth of invention. From a

certain degree of stylistic

malauroitness,

which he later avoided and

which he also smoothed over

during a subsequent editing

of the work, we can conclude

that the composition still

emanated from the Arnstadt

period. The chorale melody

lies in the bass. It is

arranged line by line with

the usual “pre-imitation”;

the conclusion is

constructed as an

ingrisification by way of

canonic bearing of the two

last chorale lines in the

double pedal.

8) Trio G major by

Telemann, BWV 586.

Whether the adaptation of

this two-part Telemann

allegro for the organ really

originates from Bach is

uncertain. The gay,

extrovert movement is a

credit to its composer.

9) Aria F major by François

Couperin, BWV 587.

This piece is, almost note

for note and without any

changes indicating an

arrangement, the middle

section marked “Légerement”

from the Troisieme Ordre of

the Couperin trio sonatas

published in 1726 under the

title “Les Nations”. A copy

from the vicinity of Bach in

which the name of the author

was missing was the reason

for the false accreditation.

This, as well as the

previous piece, show that

one was capable of playing

as an organ trio on two

manuals and pedal,

frequently without any

alteration, movements from

trio sonatas for two melody

instruments and basso

continuo.

10) Fantasia C minor.

Max Seiffert published this

work for the first time. It

was handed down in the

so-called "Andreas Bach Book", a

collection of manuscripts

from the vicinity of Bach at

the beginning of the 18th

century, without any note as

to author and in German

organ tablature. Judging

from its strength of

combination, the excellent

work could certainly have

come from the young Bach.

11) Fugue G major, BWV

577. The mobile work

in gigue rhythm, which is

worthy of attention if only

because of the convincing

use of the pedal, is from

the point of view of origins

only weakly authenticated as

a Bach composition: from the

point of view of its style,

one could hardly deny that

it originated from the young

Bach.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

This critical

and complete stylistic

survey of Bach's

organ works is

the fifht part

and will be

continued by

further

releases.

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|