|

|

2 LP's

- BC 25101-T/1-2 - (p) 1968

|

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 847 - (p) 1968 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 848 - (p) 1968 |

|

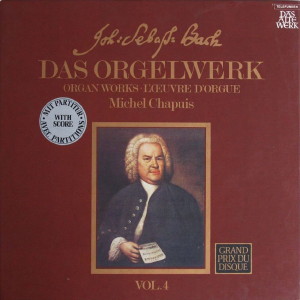

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 847) |

|

|

| Präludium und

Fuge h-moll, BWV 544 |

11' 08" |

|

| Präludium und

Fuge c-moll, BWV 549 |

5' 11" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge G-dur, BWV 550 |

6' 20" |

|

|

|

|

| Präludium

und Fuge e-moll, BWV 533 |

5' 00" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge C-dur, BWV 531 |

5' 41" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge g-moll, BWV 535 |

7' 13" |

|

| Fantasie

und Fuge (Fragment) c-moll,

BWV 562 |

6' 34" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 848)

|

|

|

| Präludium

(Toccata) und Fuge F-dur, BWV

540 |

14' 00" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge D-dur, BWV 532 |

9' 52" |

|

|

|

|

| Präludium

und Fuge C-dur, BWV 547 |

8' 45" |

|

| Präludium

und Fuge e-moll, BWV

548 |

14' 04" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

| an

der Arp Schnitger-Orgel

der St. Michaelis-Kirche,

Zwolle/Holland |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Zwolle

(Olanda) - luglio 1968 (LP 1)

& agosto 1968 (LP 2) |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 847 · Vol. 7 - (1 LP) -

durata 47' 07" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 848 · Vol. 8 - (1

LP) - durata 46' 41" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25101-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 47' 07" / 46' 41" - (p)

1968 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Bach’s

artistic development is

effected first of all in

organ music and in what,

initially, was piano music

of a style that scarcely

differed from it. After

passing through the Latin

school in Ohrdruf and Lüneburg,

and then taking a brief

temporary post as violinist

in the Weimar court

orchestra, he became

organist at the new church

in Arnstadt in 1703 at the

age of 18; he had shortly

before inspected and

inaugurated the church’s new

organ. In 1707 he

transferred his organist’s

activities to the larger

organ at St. Blasius Church

in Mühlhausen,

and a year later became

“Organist and Kammermusicus”

at the Court of Weimar. At

least until early 1714, when

he was appointed leader and

regularly had to compose and

perform cantatas, he was

primarily occupied with his

organist’s duties. Thus in

the eleven years between

1703 and 1714 most of his

organ works were composed

which form chorale

arrangements “bound” to a

hymn tune, as well as the “

free” organ works consisting

mainly of the preludes and

fugues.

We do not know the exact

dates of when the individual

works were composed;

instead, starting from the

few works which can be given

a precise date, we have to

draw conclusions as to the

sequence of the remainder.

In this respect, source

research and analysis of

style complement each other.

With a certain amount of

reservation, the tone volume

of the pieces also provides

some indications as to time;

for the organs which Bach

played in Arnstadt, Mühlhausen

and Weimar differed with

regard to the extent of the

pedal and keyboards.

However, this type of

investigation takes us back

only as far as the Arnstadt

period. Which works Bach had

already taken there with

him, to what degree he was

already independent as a

composer at the age of 18 is

something of which we are

not aware. Nevertheless, in

those works capable of

dating we can already

observe an astounding

development, both in style

detail and in the formal

arrangement. In the early

works the harmonic

modulation makes an erratic

in inconstant impression,

not yet being used in a

planned manner for the

tension-laden construction

of major forms. The basses,

at first dependent supports

for the melody, are

gradually given a more

independent role and

establish the immediate

compositional continuity.

Bach arranged thematically

and enlivened the sequences,

that is to say the frequent

repetitions of the same

theme-figure in a different

tone degree. This process

would have been

inconceivable without Bach’s

disputation with

contemporary Italian music.

From now on Bach

incorporated its song-like

quality in his own

instrumental music. This

already becomes apparent in

his fugue themes. They are

carried in vocal style and

eschew what until then had

been the somewhat obstrusive

instrumental figuration

which he had learned from

North German models. He took

over from the new Italian

solo concerto the generously

proportioned and clearly

structured formal

arrangement, based on the

change from pithy ritornello

thematic and richly

contrasting solo episodes by

way of a broadly spread

harmonic basic outline.

Bach’s fugues are affected

by this as much as the

preludes. Over and above

this he perfected what was

probably his inborn gift of

combination, his

contrapuntal art. The organ

works in the present series

provide examples from his

various stages of

development, from the

carefree toccata-like pieces

which open with a dash from

the Arnstadt era, to the

grand Leipzig organ works.

A fair copy manuscript by

Bach of the Prelude and

Fugue, B minor, BWV 544,

from around the year 1730

has been preserved. The work

itself was undoubtedly

composed only a short time

previously since it bears

all the traits of Bach’s

mature art. In the

concerto-style constructed

prelude in 6/8 time, a long,

fantasia-type ritornello

alternates three times with

a fugal episode. The two

passages are transformed in

the recurrence. The sections

of the ritornello are

transposed and extended

thematically, the episode

shortened and contrapuntally

more tightly-knit. The fugue

contrasts with this complex

prelude not only in the

theme style, but even more

on account of the uniformity

of its material and motion

form. The theme, which in

quaver movement paraphrases

the rising triad tones and

again leads back to the

ground tone, also dominates

the intermezzos with the

subsequent counterpoint. A

long manualiter centre part

provides the necessary sound

contrast.

Prelude and Fugue, C

minor, BWV 549 are

among the earliest of Bach’s

works to be passed on to us.

The original version was in

D minor, and we do not know

whether

that generally played at the

present time in C minor was

not perhaps a posthumous

arrangement for an organ the

pedal of which extended only

as far as c’. As in many

other youthful works by

Bach, the prelude begins

with a pedal solo and in

simple intensification by

way of organ points leads

quickly to the conclusion.

The fugue, with its long and

somewhat obstrusive

descending cadenza theme,

links up with the prelude.

The pedal entry is reserved

for the conclusion of the

second development. A long

virtuoso coda in particular

shows that in this case the

old multi-part toccata

served as a pattern, in

which the virtuoso-figurative

sections alternate with

fugal parts.

Prelude and Fugue, G

major BWV 550, like

many other G major pieces by

Bach, radiate light-hearted

joy. Shadows are almost

completely absent, and it

requires considerable

interpretative stamina to

prevent this piece,

extremely long in relation

to its simple construction,

having a wearying effect.

The fugue theme, with its

upbeat repetitive crotchets

and its counterbeat broken

triads is headed “alla breve

e staccato”: for this reason

it must not be gracefully

played down. With graduated

entries starting from the

top, the prelude first moves

on to a long pedal solo and

then in reverse sequence

builds up on this an

intensified section. A short

modulation middle section

has the task of once more

diverting attention from the

principal key already

reached in order to prepare

for entry of the fugue in

the dominant. Judging

from its style, the work

dates back to the Weimar

period.

It is scarcely possible to

conceive a greater contrast

than between this piece and

the short Prelude and

Fugue, E minor, BWV 533,

a youthful work which

touches us with the warmth

of its feeling. The

development thématique of

the prelude, a harmonically

rich movement, gives prior

notice of Bach’s art of

consistently further

developing a concept. Here

it is a case of heightening

the syncopes to sharp

counterbeats and forming the

conclusing with the “below

stairs figure” of the bass.

Both concepts emerge

voluntarily from the

preludes, gain firm shape by

repetition and show in the

process how improvisation

fuses into composition. The

fugue dispels any thought of

strictly observed theme

technique. As in a long

drawn out aria, the

counterpoints incorporate

the theme - clearly jointed,

but nevertheless avoiding

any clear break.

Prelude and Fugue, C

major, BWV 531 is

certainly one of the very

earliest works. We recognize

this not only from various

stylistic deficiencis, which

probably disturb the eye

more than the ear, but even

more clearly from the

disproportion between the

boldly forward-moving

impulse of the themes, and

the still little developed

shaping strength. Thus,

great arcs of tension are

built up but do not follow

through. In the final

analysis it is the player,

who with his momentum, has

to join the pieces together

into a whole, and not the

music of itself compelling

the unity of the whole.

Young Bach will have

fascinated his listeners

with these pieces, but he

himself was the first to

recognize their

shortcomings. His studies of

foreign examples,

particularly of the Italian

masters, but also his own

formal experiments spread

over many years, appear to

have been directed towards

developing the possibilities

which accorded with his

inventive powers in order to

construct larger, more

compelling forms.

Among the very few youthful

Works of Bach which have

come down to us in autograph

form are the Prelude and

Fuge, G minor, BWV 535.

According to Bach’s written

characters in the famous “Möller

Manuscripts”, the main

source of information for

Bach’s early works, this

effective piece must have

been composed in the middle

Arnstadt years, certainly

not later than 1706. At that

time, however, the prelude

was of a much more modest

shape and was scarcely half

as long. Above all the

14-bar long chromatic

sequence was missing,

leading from F-sharp in

semitone steps by way of a

tenth down to D. Similarly

Bach did not compose until

later the accord at the head

of the fugue theme in the

pedal part, bars 10 to 11 of

the prelude: It is only this

tension-laden anticipation

that motivates the long

sequence. The fugue on the

other hand required only

little alteration. It is a

text book example of how a

significant theme also

dictates the appropriate

arrangement.

We are also able to trace

the origins of the Fantasia

C minor, BWV 562 and

its fragmentary Fugue on the

basis of the autograph. The

Fantasia originates from the

beginning or the middle of

the 1730’s.

It was not until much later,

in the 1740’s, that Bach

composed the Fugue to go

with it, but apparently did

not complete it. The present

recording ends with the

dominant cadence after the

first exposition. In the

manuscript, which breaks off

five bars later, the

beginning of a stretto

follows, and it can be

assumed that further

contrapuntal combinations,

perhaps also the

introduction of a second

theme, were planned.

Compensation for this torso

is provided in the shape of

the Fantasia, which in its

own right is an incomparable

work: devoid of all external

outbursts. the tightlywoven

but always vocal imitative

movement has the effect of

music which requires no

intermediary, but which

appeals directly to the

senses.

Toccata and Fugue, F

major, BWV 540 have

been handed down separately

in various manuscripts, and

it is quite possible that

Bach compiled these two

inordinately long movements

only subsequently to this

monumental pair of

movements. The toccata

originates from the middle

Weimar period. It combines

the grand lucid

concerto-type arrangement

with long toccata-style

developments by way of the

organ point and with

extensive pedal solos. The

exposition is repeated on

the dominant. From the

cadence chords which

concludes them Bach gains a

sequence motif which is now

carried on in alternation

with a new theme and the

thematic material of the

exposition. The fugue was

probably composed later. Its

chromatically introduced

ricercare theme is

confronted in a centre

section manualiter with a

second, more playful theme,

which in the final part is

brought together with the

principal theme.

The Prelude and the

Fugue, D major, BWV 532

were probably originally

composed independently of

each other. The sources say

nothing about the time of

their composition, but

judging from the style they

are early works, going back

to the Arnstadt era. The

fugue is the virtuoso

brilliant work among the

youthful pieces. With the

obtrusive caesura of the

long figurative theme Bach

carries out a practical joke

and plays with a blustering

counterpoint into the pause

between the fore movement

and continuation of the

theme. An earlier version of

the fugue was considerabyl

shorter. In the final

version Bach better disposes

of the individual voices and

extends the second part. The

prelude accords with the

formal model of a threepart

toccata. A chordal-figurative

introduction is followed by

a concertante “alla breve”,

in the Italian style, which

unconcernedly makes use of

sequence chains. An adagio

forms the coda.

Prelude and Fugue, C

major, BWV 547

originate from the middle

Leipzig period. Hardly any

other organ work of this

extent is so tightly-knit

and so consistently

renounces figurative

episodes, despite the

concerto-type arrangement.

Nevertheless the listener

scarcely notices this

combinative effort:

everything is lucidly

structured. The prelude with

its double exposition is

arranged in similar fashion

to the grand F major

Toccata, BWV 540, only that

it is very much more

concentrated. The fugue

reserves pedal use until the

last exposition and

processes the theme first in

similar motion, then in the

reversion. The fourth

exposition brings similar

and reverse form in stretto,

the fifth repeated stretti

via the augmented theme in

the pedal. Incidentally

one has the impression that

in this work Bach for a

definite reason consciously

kept the pedal part easier

than in others: both in the

Prelude and in the Fugue he

waives rapid passages.

Prelude and Fugue, E

minor, BWV 548 are, in

addition to the large-scale

movement pair in E-flat

major from the III.

part of the “Klavierübung”,

the most powerful of Bach’s

late organ works. According

to a part autograph, it will

also have been composed

towards the end of the 1730’s.

The prelude combines the old

figurative-chordal

mode of play of the toccata,

its development by way of

organ points, with clearly

structured concerto-style

construction. The fugue,

which from time immemorial

has been regarded as the

boldest and technically

most difficult of the Bach

fugues, is what is known as

a “da capo fugue”: after a

clearly contrasting centre

section the opening part is

repeated note for note. From

the tension-packed theme,

which is based on the

principle of interval

expansion, one can already

gain a picture of Bach’s

artistic development: it has

evolved entirely from the

idiom of the instrument,

already non-vocal on account

of the pendulum motion,but

at the same time possessing

the unity of his fugue

themes formed on the Italian

style.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|