|

|

2 LP's

- BC 25100-T/1-2 - (p) 1968

|

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 845 - (p) 1968 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 846 - (p) 1968 |

|

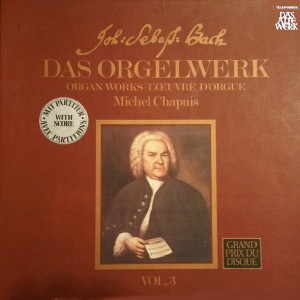

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 845) |

|

|

| Präludium

(Toccata) und Fuge (dorisch)

d-moll, BWV 538 |

12' 54" |

|

| Präludium und

Fuge c-moll, BWV 546 |

10' 41" |

|

|

|

|

| Präludium und Fuge G-dur,

BWV 541 |

7' 05" |

|

| Präludium und Fuge d-moll,

BWV 539 |

7' 12" |

|

| Präludium und Fuge a-moll,

BWV 543 |

9' 10" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 846)

|

|

|

| Präludium und Fuge C-dur,

BWV 545 |

5' 08" |

|

| Präludium und Fuge f-moll,

BWV 534 |

7' 43" |

|

| Präludium und Fuge A-dur,

BWV 536 |

6' 33" |

|

|

|

|

| Präludium (Fantasie) und

Fuge g-moll,

BWV 542 |

11' 17" |

|

| Präludium (Fantasie) und

Fuge c-moll,

BWV 537 |

7' 49" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

| an

der Arp Schnitger-Orgel

der St. Michaelis-Kirche,

Zwolle/Holland |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Zwolle

(Olanda) - marzo 1968 (LP 1) &

ottobre 1967 (LP 2) |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 845 · Vol. 5 - (1 LP) -

durata 47' 02" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 846 · Vol. 6 - (1

LP) - durata 38' 30" - (p) 1968 -

Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25100-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 47' 02" / 38' 30" - (p)

1968 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Preludes

and Fugues

Toccata, fantasia, prelude

and fugue are old forms of

instrumental music,

particularly piano and organ

music, going back to the

early 16th century;

nevertheless it was left to

Bach to give them that

artistic shape in which they

have since lived on as

patterns. This applies

especially to the prelude

and fugue as well as to

their combination into

complementary dual

movements. Their origins

consist of two contrary

principles of arrangement:

Free ranging, homophony,

virtuoso brilliance in the

toccata, in the prelude

related to it and the free

fantasy; as opposed to this,

strict thematic linking,

polyphony, build-up of the work

from imitative developments

with regard to the fugue.

The prelude and fugue were

originally intended to test

the tuning of the

instrument, to give the

other players or singers the

key and to prepare the

audience for the following

performance. These

introductory pieces were

improvised and developed

entirely according to the

mode of play of the

instrument: sustained chords

alternated with fast runs

and passage work. When

musicians began to compose

them properly and provide

scoring, more strictly

arranged, polyphonic

sections were also soon

incorporated. However, these

pieces always retained

something of the ranging

character in the

improvisation. The fugue on

the other hand goes directly

back to the vocal polvphony

of the 16th century. Its

preliminary forms, the

ricercare and the

instrumental canzona, were

initially instrumental

copies of the vocal

motets and the French

chanson.

A good deal of its varying

thematic process has been

maintained in the Bach fugue

subjects. Thus we

have in the present

selection, for instance, the

organ fugues in D minor BWV

538 and F minor BWV 534,

typical ricercare themes

which are hardly able to

deny their origins in the

motet. The G minor fugue BWV

542 on the other hand has

something of the rhythmic

drive and song-like

construction of the chanson.

In the ricercare and in the

canzona, just as in their

vocal prototypes, imitative

sections were joined on to

one another with the

appropriate new thematic

material. The decisive move

towards the fugue consisted

of the thematic unification

and broadening of the shape,

no longer by merely setting

out in a row, but by way of

harmonic and contrapuntal

methods, as well as by pithy

intermezzos. This was

introduced in the 17th

century, but it was only

Bach who finally consummated

it. In this respect the wide-ranging

modulation plan and the

clear separation of

developments and intermezzos

are inconceivable without

the example of the Italian

solo concertos, which

incidentally also played a

contributory part in

determining construction of

many preludes. Finally it

was also Bach who combined

the basically different

design forms of the prelude

(toccata) and fugue into a

firmly established dual

movement. Bach began his

music career at the age of

18 as organist. He

discovered his own style in

organ music, and it was for

the organ that he created

his earliest masterpieces.

Fuller details of his

artistic development, as

recorded in his analysis of

the traditionel forms of

organ music, are contained

in the notes with the fourth

album of Bach’s organ works.

The present third album

contains ten of the

large-scale preludes

(toccatas, fantasias) and

fugues arranged as dual

movements, including some of

the most famous. They cover

a period between about 1708

and 1740. The homogeneity of

the movement twosome in most

cases emerges strikingly

from their thematic

relation. More important

than this, however, is the

inner mutual dependency of

the two movements which no

doubt can only be described

more or less as the

principle of tension and

release.

Toccata and Fugue D minor

BWV 538 -- because of

the absence of the B

signature usual with the D

minor, erroneously

interpreted as church mode,

and called the “Doric

Toccata“ - is one of the

early master works und was

undoubtedly already composed

in the initial Weimar years,

between 1710 and 1714. The

introductory toccata

displays the influence of

the Italian concerto

movement, with its

alternation from tutti to

solo passages. Bach laid

down to the last detail in

this one case the manual

change between swell-organ

and positive. In this regard

it is a sound and not a thematic

change. The purpose is to

keep alive and further

consolidate the powerful

semi-quaver motion which

is maintained throughout

the entire movement. In

the same irrevocable

manner the mighty,

expressive fugue moves on

towards its goal without

any resting point. Its

broadly based theme, with

suspensions and syncopes,

is counterpointed with two

retained counterparts and

frequently borne in close

harmony.

Prelude and Fugue C

minor BWV 546 were

not composed until Bach’s

Leipzig period, and hardly

before 1730. The stylistic

further development is

best recognized in the

prelude, incorporating

thematic abundance and

concurrent fantasy into

lucid construction, which

again is based on a

concerto movement. In this

case ritornello and outer

movement are also

thematically clearly

distinguished. The long,

multilinked introductory

ritornello, which is

repeated at the end,

develops by way of the

three organ points of the

tonic, dominant and

subdominant, as the

evolution from a brief

thematic nucleus, the

suspension motif. Then, in

a grand harmonic curve,

follow the outer movement

and ritornello in a triple

change, being shortened,

modified and extended - a

section of the outer

movement is even worked

into the penultimate

ritornello. After this so

rich and complex movement,

the five-part fugue is

especially effective

because of the compelling

power of its unusual

subject. Its compact

movement is loosened up

with long minor part

intermezzos.

Prelude and Fugue G

major BWV 541 is one

of the few free organ

works which have been

passed on in Bach’s own

handwriting, a fair copy

from the 1740’s.

The composition itself was

most probably written 20

years earlier. The prelude

opens with a long solo

figure, establishing a

ritornello-type tutti

block which -- interrupted

by short solo passages -

continues in the same

vein. Starting from

rhythmical organ point D

the conclusion is reached

without a great deal of

digression. It is a

concise piece, of

breath-taking joy. This

jubilation carries on in

the fugue. The

introductory tone

repetitions of its theme

should not be construed in

the sense of the

hammering, knocking

battaglia motifs of the

North German organ school,

but of joyful, inner vitality.

Prelude and Fugue D

minor BWV 539 were

evidently not included in

the complementary set

sequence until the 19th

century. The fugue is

well-known as the 2nd

movement of the violin

solo sonata G minor, BWV

1001/2. The present

transcription for the

organ, an effective piece

featuring strong chords,

is more likely to have

been by one of the sons or

pupils of Bach than by

himself. Supporting this

theory are not only

stylistic reasons, but

also the tradition, which

did not begin until the

end of the 18th century.

It is improbable that the

modest prelude, to be

played only on the

manuals, belonged to it

from the outset. According

with contemporary

performance practice,

Michel Chapuis plays the

continuous quavers of the

prelude as “notes

inégales“, i.e., in

pointed rhythm. By way of

such movements our

attention is drawn to the

arrangement techniques

generally observed in

Bach’s time and applied by

Bach himself in a masterly

fashion; they are never

insignificant movements

prepared for another

instrument in this manner.

Prelude and Fugue A

minor BWV 543 no

doubt already originate

from the Weimar period,

although their tradition

does not begin until very

much later. In two widely

projecting passages, of a

definite toccata-type

shape, the prelude

prepares the extensive

fugue. The first is a

figurative solo which

intensifies by way of an

organ point extending over

23 bars. The second, also

starting as a figurative

solo, completes this

intensification with the

aid of a more

tightly-knit, chordic

imitative movement. The

fugue develops from a

high-spirited theme in 6/8

time into a virtuoso piece

with long intermezzos and

a toccata-like conclusion.

That the musical current

in this movement largely

consisting of sequences

does not dry up is

probably due, on the one

hand, to the artistic

theme whose pre-movement

continually keeps alive

the regular flow of motion

by shifting the rhythmic

points of emphasis, and on

the other hand to the

ingenious puzzle game

carried on with deceptive

developments emerging from

the intermezzos.

Prelude and Fugue C

major BWV 545 belong

to Bach’s Weimar period.

The autograph, which still

existed around 1900, has

disappeared. A shorter

version of the prelude

shows that this

toccata-type movement only

received by the addition

of three bars in front and

behind that compulsive,

balanced form in which it

is still presented today.

The fugue lives entirely

from the force of its

theme, stretching from

triple onset of speech to

the octave, the rear set

of which simultaneously

counterpoints the fore set

in opposing motions. It

is, however, more quickly

ended than one would

expect, precisely on

account of this theme.

Perhaps this is on account

of the succeeding largo

which

in some instances is

placed after the fugue and

which otherwise we know as

the centre movement of the

5th organ trio, BWV 529.

Prelude and Fugue F

minor BWV 534 has

come down to us in only

one copy from the early

19th century: evidence of

how many coincidences the

passing on of even highly

significant works was

dependent upon. The

composition probably

originates from the Weimar

period. The two-part

prelude is built up as

continuation from the

toccata-like semi-quaver

figuration over the organ

point. The fugue contains

a good deal of

chromaticism and

cross-relations. Even its

theme is dominated by the

diminished seventh leap

downwards. After the first

extended and tightly-woven

development part,

intermezzos alternate with

only brief thematic

sections in order to

enable the last theme

onset in the bass and alto

to come to the fore all

the more effectively.

There is only an early version

of the Prelude and

Fugue A major BWV 536

which apparently goes back

to the Arnstadt period.

Subsequently Bach

considerably rearranged

the prelude, and

transposed the fugue from

its original 3/8 time to

3/4; but apart from

increasing the note values

and shortening the

conclusion by two bars he

scarcely changed anything

of the latter. The terse

prelude develops in

toccata style, initially

with rising and descending

triad figurations by way

of organ points, then in

imitative setting of this

figuration. The fugue is

concise but arranged with

continually alternating

counterpoint. Shortened

inserts in the centre

section give notice of the

close melodic lead which

heralds the concluding

section. In the graceful

song-like theme the

rhythmic points of

emphasis change from bar

to bar, so that a peculiar

hovering metre ensues. It

is hardly likely that

anybody would be able to

detect the proper rhythm

of the theme after hearing

it only once.

Fantasia and Fugue G

minor BWV 542 are

the boldest and

technically most difficult

pieces in the present

selection. They have

frequently been connected

with Bach’s application

for the organist’s post at

the St Jakobi

church in Hamburg in the

year 1720; the fugue, the

theme of which derives

from a Dutch folk song,

has been regarded as

homage to the elderly

Hamburg organist Jan

Adams Reinken. However, at

least the fantasia has

been passed on in

autographs from Bach’s

Weimar period.

Harmonically it is one of

Bach’s most courageous

pieces, and in this sense

absolutely comparable to

the “Chromatic Fantasia“.

In the manner of the old

toccata, figurative

passages alternate with

chordic and imitative. The

fugue is not only arranged

in virtuoso and

concertante style, but is

also constructed like a

concerto movement, with

the theme developments

taking over the role of

the tutti, and the

intermezzos that of the

solo. The two movements,

fantasia and fugue, were

handed down individually

in numerous autographs and

thus apparently not until

some years after

composition were combined

by Bach into a dual

movement.

Fantasia and Fugue C

minor BWV 537 again

were handed down in only

one manuscript, which,

however, gives no

indication as to the date

of composition. The

fantasia is related to the

early Baroque fantasia,

which as yet does not

raise free-ranging

concepts to a principle of

form, but in the style of

the motet and chanson

joins imitative sections

on to one another. Bach

constructs from this a

two-part reprise form. The

fugue too keeps to the

reprise form: its

conclusion is a prolonged

da capo of its exposition.

The centre section is made

independent by the

introduction of fresh

counterpoints. Bach

frequently used this form

of the “da capo fugue“ in

his organ and lute fugues

of the later Leipzig

period.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

*

This critical and complete

stylistic survey of Bach’s

organ works is the third

part and will be continued

by further releases.

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|