|

|

2 LP's

- BC 25099-T/1-2 - (p) 1970

|

|

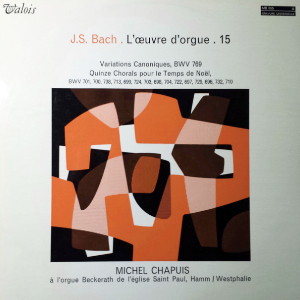

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 855 - (p) 1969 |

|

| 1 LP -

Valois MB 856 - (p) 1970 |

|

| DAS ORGELWERK -

VOL. 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann

Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 - (Valois MB 855) |

|

|

| Kanonische

Veränderungen über "Vom Himmel

hoch, da komm' ich her", BWV

769 |

10' 10" |

|

| Fughetta super

"Vom Himmel hoch, da komm' ich

her", BWV 701 |

1' 16" |

|

| Vom

Himmel hoch, da komm' ich her",

BWV 700 |

1' 15" |

|

| Vom

Himmel hoch, da komm' ich her",

BWV 738, 738a |

2' 46" |

|

| Fantasia

super "Jesu, meine Freude",

BWV 713 |

5' 31" |

|

|

|

|

| Fughetta

super "Nun komm', der Heiden

Heiland", BWV 699 |

0' 52" |

|

| Gottes

Sohn ist kommen, BWV 724 |

1' 12" |

|

| Fughetta

super "Gottes Sohn ist kommen",

BWV 703 |

0' 44" |

|

| Fughetta

super "Herr Christ, der ein'ge

Gottes-Sohn", BWV 698 |

1' 04" |

|

| Fughetta

super "Lob sei dem allmächt'gen

Gott", BWV 704 |

0' 54" |

|

| Gelobet

seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV

722, 722a |

2' 48" |

|

| Fughetta

super "Gelobet seist du, Jesu

Christ", BWV 697 |

0' 54" |

|

| In

dulci jubilo, BWV 729, 729a |

4' 05" |

|

| Fughetta

super "Christum wir sollen loben

schon", BWV 696 - (oder: Was

fürcht'st du, Feind Herodes, sehr) |

1' 22" |

|

Lobt

Gott, ihr Christen. allzugleich,

BWV 732, 732a

|

2' 42" |

|

| Wir

Christenleut' habn jetzund Freud,

BWV 710 |

2' 06" |

|

Long Playing

2 - (Valois MB 856)

|

|

|

| Wachet

auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV

645 |

4' 27" |

|

| Wo

soll ich fliehen hin, BWV 646 |

1' 29" |

|

| Wer

nur den lieben Gott läßt walten,

BWV 647 |

2' 56" |

|

| Meine

Seele erhebet den Herren, BWV

648 |

1' 44" |

|

| Ach

bleib' bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ,

BWV 649 |

2' 47" |

|

| Kommst

du nun, Jesu, vom Himmel herunter,

BWV 650 |

3' 16" |

|

| Fuga

sopra il Magnificat, BWV 733 |

3' 53" |

|

|

|

|

| Allein

Gott in der Höh' sei Ehr',

BWV 715 |

1' 42" |

|

| Allein

Gott in der Höh' sei Ehr',

BWV 711 |

2' 34" |

|

| Allein

Gott in der Höh' sei Ehr',

BWV 717 |

2' 28" |

|

| Wo

soll ich fliehen hin,

BWV 694 |

3' 26" |

|

| In

dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr,

BWV 712 |

2' 04" |

|

| Christ

lag in Todesbanden, BWV

718 |

4' 30" |

|

| Christ

lag in Todesbanden, BWV

695 |

4' 06" |

|

|

|

|

| Michel Chapuis |

|

an

der Beckerath-Orgel der

Paulus-Kirche, Hamm/Wesfalen (LP 1)

|

|

| an

der Andersen-Orgel der St.

Benedikt-Kirche, Ringsted/Dänemark

(LP 2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

- Hamm,

Wesfalen (Germania) - luglio 1969

(LP 1)

- Ringsted (Danimarca) - agosto

1970 (LP 2) |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Michael

Bernstein |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- Valois

- MB 855 · Vol. 15 - (1 LP) -

durata 39' 41" - (p) 1969 -

Analogico

- Valois - MB 856 · Vol. 16 - (1

LP) - durata 41' 22" - (p) 1970 -

Analogico

|

|

|

"Das Orgelwerke" LP |

|

Telefunken

- BC 25099-T/1-2 - (2 LP's) -

durata 39' 41" / 41' 22" - (p)

1970 - Analogico |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach: Organ

Works *

Chorale

Arrangements I

That Bach’s organ music, and

in its wake organ music

generally, is regarded as

the expression of Protestant

Christianity as such is not

an inevitable development.

It is rather an admittedly

beautiful, but later,

historical projection: it

reveals more about ourselves

than about the church of the

Reformation period and the

time in which Bach lived.

For organ music and

organists had to struggle

for a long time in the

Lutheran church for

recognition. Looked upon as

an originally heathen

instrument which distracted

the faithful from the

service, the organ was

threatened with banning. It

was not until 1597 that the

Wittenberg theological

faculty ended the long

dispute about the legality

of organ music with, as it

were, a declaration of

non-impediment - and by no

means with a special

recommendation.

The fact that organ music

finally asserted itself in

the church service was due,

initially, not to the grand,

concert-type fantasias and

toccatas, the preludes and

fugues, the so-called “free”

organ works which were

always regarded only as an

ingredient and as external

ornamentation: its influence

goes back rather to “chorale

arrangements”, that is to

say, to those compositions

which are based on the

melody of a hymn or on

another part of the liturgy.

“Bound” organ music is so

called on account of its

connection with a

predetermined cantus firmus.

In Lutheran church services

the hymns sung by the

congregation were a firm,

integral part of the

liturgy. They could not be

omitted at will, abridged or

replaced by others; they had

to be sung in their entire

verses. However, the

congregation, choir and

organ could alternate

according to verses. Indeed

it was even possible for a

choral of many verses

to be rendered in purely

instrumental form. The

custom which we are used to

today, with the organ having

to accompany the

congregation’s singing, did

not arise until the 17th

century. The alternation

system was maintained side

by side with it for a long

time. The non-vocal

performance of a choral

verse or of an entire

chorale applied equally to

the sung word and could

replace it. This was the

great opportunity for the

organists. They did not

restrict themselves to

performing the verses

entrusted to them in simple

chordal phrases, but devoted

all their ability to shaping

the choral melody into their

own polyphonic work of art

with the aid of counterpoint

and harmony. In the song

variations of the English

virginal players and of the

great Dutch organ master

Sweelingk, as well as in

their own vocal music above

a cantus firmus, they

discovered fresh ideas for

this purpose with whida they

were able to develop further

the old organ playing

practice of choral

arrangement. Simultaneously

with this, organ

construction was being

perfected. Organs were

becoming more richly

equipped and -- particularly

in Northern Germany - the

pedal was being strengthened

as regards the stops. It was

certainly not used solely as

a basic tone, but with its

strong and clear 4-foot and

2-foot registers often

served in the choral

arrangements to represent

the choral melody. (The “Schüblerschen”

chorales Nos. 2, 3 and 6

included in this album are

instructive examples of this

type of use of the pedal.)

In 1624 the organist Samuel

Scheidt

of Halle had submitted with

the third part of his

“Tabulatura nova” a classic

work for the various

possibilities of choral

arrangement. In the second

half of the 17th century

they were further developed

in the North German

organists school connected

with Buxtehude, and in

Southern Germany,

particularly by Pachelbel.

As a consequence of

religious intensification

during the pietism period,

the composers tried more

purposefully than before to

express the verbal statement

of the individual choral

verses in musical phrase, to

interpret the choral text by

musical means. With his

choral arrangements Bach was

therefore able to call upon

a riduly developed treasure

of forms and modes of

expression. By far the

greater part of his bound

organ works was composed in

the period from 1703 to

1714, when as organist in

Arnstadt, Mühlhausen

and Weimar, he himself was

responsible for the

liturgical organ music.

During the period as court

musical director in Köthen

and in the first years in

Leipzig organ composition

had to make way for other

tasks. It was only later

that he turned to the organ

again, now quite clearly

giving preference to choral

bound over free organ music:

in 1739 he published a

wide-ranging collection of

chorale preludes under the

title “Clavierübung.

Dritter Teil”. In 1746 he

published the six “Schüblerschen

Choräle”,

and a year later the

“Canonic Variations on ‘Vorn

Himmel hoch, da komm ich

her”’. In addition he

started an autograph

collection of particularly

brilliant dmoral

arrangements which are known

as the “Eighteen Chorales”.

At least the later works

were probably not composed

exclusively for church

services, but also for

concert-type performance.

Bach was the most famous

organ player of his time and

in this capacity enjoyed a

greater reputation among his

contemporaries than as a

composer. He constantly gave

extremely successful public

organ recitals. On these

occasions in addition to

free organ compositions he

improvised on hymns. A

series of works which have

come down to us to the

present day probably

originate from such

improvisations which Bach

subsequently worked out in

detail and recorded in

writing. But regardless of

whether a choral arrangement

was composed for liturgical

or non-liturgical use: just

as with the set melody, the

text of the choral also

binds the composer and

channels his powers of

invention into a certain

direction. Bach, like none

of his predecessors,

elucidated and gave a

stronger meaning to the

verbal statement of the

choral. Thus if one is to

understand his compositions

it is also necessary to know

the choral texts. In this

connection one has to bear

in mind that verse songs are

involved. The one melody and

the single arranged

polyphonic theme must not be

suitable for only the first

or for a certain verse, but

for all verses of the hymn.

The composer will thus be

less inclined to depict the

individual phrase in music,

but will rather try to

impart the content of the

whole. Where, as is

frequently the case with

hymns, various choral texts

are sung to the same melody,

the theme had from the

outset to be kept in a

neutral vein. It is then

part of the organist’s art,

by appropriate registration

and lively performance, to

adapt the music text to the

corresponding purpose. Where

he played to written music

his task was also of a

creative nature, and this

element of improvisation in

art music has been retained

to the present time only in

the case or organists.

The present album contains,

in addition to the famous

“Canonical Variations on

‘Vom Himmel hoch, da komm

idx her”’ and the six “Schüblerschen

Choräle”,

numerous choral arrangements

from Bach’s early period:

works which he had evidently

not incorporated in larger

collections and whidm

therefore have been handed

down in the most varied

autographs. In the present

recording they are

provisionally collated

according to liturgical

points of view. On the first

record the canonical

variations on “Vom Himmel

hoch” are followed by three

further arrangements of this

Christmas song as well as

other chorals of the advent

and Christmas season.

Following the “Schüblerschen

Choräle",

which belong to the various

liturgical rules, the second

record features a fugue to

the magnificat, three

arrangements of the gloria

“Allein Gott in der Höh’

sei Ehr” and two hymns of

supplication and consolation

and, together with the two

themes on “Christ lag in

Todesbanden”, leads into the

Easter period.

The term “choral

arrangement” is a modern

collective expression for

the numerous and stylistically

clearly differentiated

arranging techniques

which have evolved in the

course of history.

Contemporaries usually had

more precise descriptions

for them: chorale

parts, chorale fantasies, chorale

fugues and fughettas organ

chorales, chorale

preludes and many other

terms. We are therefore

summarising the numerous

individual chorale

preludes in the present

album in accordance with

formal criteria of this

kind.

1. Chordal styles

accompanying the

congregation’s singing.

When it became the custom to

accompany the congregation’s

singing on the organ,

organists acquired the habit

of separating the individual

choral lines from eadi other

by means of shorter or

longer “tirades”, virtuoso

passages on the particular

concluding pauses-a practice

which in the following

period was rigorously

opposed as being a

distortion of church choral

singing. There are six

pieces of this type by Bach,

of which

our album contains five: BWV

738 Vom Himmel hoch; BWV 722

Gelobet seist du, Jesu

Christ; BWV 729 In dulci

jubilo; BWV 732 Lobt Gott,

ihr Christen, allzugleich;

BWV 715 Allein Gott in der Höh’

sei Ehr’. These are

evidently youthful

experimental works, since

Bach did not return to their

style in later years.

Because of their unusual

harmonic connections and the

often abrupt transition of

the “tirades” to the

subsequent choral line, it

is difficult to imagine

these settings as an

accompaniment to the vocal

efforts of the congregation,

and they already proved a

source of trouble to

contemporaries. In 1706 the

Arnstadt consistory charged

that Bach was producing in

the choral “many strange

variations, mixing many

alien tones (keys) so that

the congregation had become

confused by this...”. Two

versions of most of these chorales

have come down to us: one of

a sketchz type and one set

out in detail. In the

present recording the

sketched version is first

played, then an inserted choral

verse in simple

harmonisation, followed by

the detailed second version.

2. Chorale fughettas and

chorale fugues

Chorale fughettas resulted

from the task of the

organist to indicate the key

and melody of the

congregation’s hymn by means

of a short prelude.

Eminently suitable for this

purpose was a short

fugue-type piece above the

first line of the choral

melody. Bach’s

seven chorale fughettas-all

of which are contained in

this album-presumably

originate from the early

Weimar period. From a

technical point of view they

are modest and intended to

be performed “manualiter”,

i. e., playing with the

hands only. They belong in

the main to the advent and

Christmas period, so that

perhaps they were conceived

as the beginning of a

collection of preludes

throughout the entire church

year, but not subsequently

maintained. The pieces are:

BWV 701 Vom Himmel hoch; BWV

699 Nun komm’,

der Heiden Heiland; BWV 703

Gottes Sohn ist kommen; BWV

698 Herr Christ, der ein’ge

Gottes-Sohn; BWV 704 Lob sei

dem allmächt’gen

Gott; BWV 697 Gelobet seist

du, Jesu

Christ; BWV 696 Christentum

wir sollen loben schon - Was

fürcht’st

du, Feind Herodes, sehr.

Whereas the chorale

fughettas are content with

imitations of the first choral

line, in the chorale fugues

the entire choral

lines are performed in fugue

style one after the other.

Among the few works of this

kind is the fugue on the

magnificat (BWV 733), which

forms an especially

convincing example.

3. The chorale fantasia

is based on the principle of

arranging all of the choral

lines in sequence, in

separately compact, often

strongly contrasting

sections, on the pattern of

the wellknown multi-part

instrumental fantasia. In

the only two bound organ

works by Bach in this

form-the fantasia super “Jesu,

meine Freude” (BWV 713) and

the fantasia super “Christ

lag in Todesbanden” (BWV

718) - the treatment of the

choral lines peculiar to the

fantasia is particularly

conspicuous. In the first

piece the entire second part

of the chorale is dealt with

only freely in a section

contrasting both as regards

movement and expression -

dolce 3/8

time. A simple chordal

realisation of the complete

choral melody forms the

conclusion. In the second

piece a long echo passage

between the swell-organ and

chair-organ develops from

the shortened sixth choral

line, preparing the way for

the highly effective finish.

4. The large organ

chorales

In most of Bach’s choral

arrangements the overall

choral melody is clearly

recognizably brought out in

at least one voice.

According to whether the

individual choral lines

succeed each other without

interludes or are separated

from one another by preludes

or interludes, one refers to

“small” or “large” organ

chorales. The present album

does not contain any

examples of the small organ

chorales without fugal

episodes as are found

particularly in Bach’s

“Orgelbüchlein”.

On the other hand it

contains all the more

“large” organ chorales:

these include all the works

not yet named and the

canonic variations on “Vom

Himmel hoch” and the “Schüblersohen

Choräle”.

With regard to the single

isolated pieces, however,

they are mostly youthful

works by means of which he

became acquainted with the

various possibilities of

choral arrangements: The

chorale cantus firmus could

appear in a simple melodic

version (as in the most

cases) or be fully

ornamented (e. g., BWV 712

In dich habe ich gehoffet,

Herr). The themes of the

counterpointed voices could

be taken from the choral or

be freely developed (e. g.,

BWV 694 Wo soll ich fliehen

hin). The most simple form

of interlude construction,

already customary with

Scheidt, was what was known

as the “pre-imitation”: each

choral line is introduced by

a short fughetta-type

imitation of the cantus

firmus, frequently in

shortened note values (BWV

700 Vom Himmel hoch; BWV 724

Gottes Sohn ist kommen; BWV

717 Allein Gott in der Höh’

sei Ehr’; BWV 712 In dich

hab ich gehoffet,

Herr). The trio “Wir

Christenleut” (BWV 710) has

also been passed on under

the name of Johann

Ludwig Krebs and probably

originates from him; Bach

described him as his best

pupil. The masterpieces of

the great organ chorales are

only found in the manuscript

and printed collections of

the later Leipzig years.

During this period Bach was

increasingly concerned with

taking the expressive force

of the music away from the

immediate elucidating media

of harmony und rhythm and

incorporating it in

contrapuntal techniques as

such. Complicated fugues and

canons become the cloak of

his last musical

interpretations. The most

important organ work of this

kind is represented by the

canonic variations of the

Christmas carol “Vom Himmel

hoch, da komm’ ich her". It

is closely related in time

to the “Musikalisches Opfer”

(Musical Offering) and the

“Art of the Fugue” and is

one of the few compositions

which Bach had printed: in

1747 he submitted it when

entering the Mizler “Societät

der Musicalischen

Wissenschaften” - a

scholarly musical society

devoted to the scientific

appreciation of music as a

mathematical discipline in

the old sense. The work is

related to such

conceptions.. In the first

to the fourth variation the

carol melody is

counterpointed with two

canonically carried voices

related to each other and

extending across the octave,

the quint, the seventh and

again the octave. In the

third and fourth variation a

further, noncanonic voice is

added. The fourth is an

augmentation canon: one

voice follows the other in

double note value. Finally

in the fifth variation the

melody is counterpointed

with its inversion, in

fourfold manner: in the

canon of the sixth, the

third, the second and the

nineth. At the end, and

forming the climax, all four

choral lines are

superimposed in short note

values above the organ pedal

point C.

Works of a quite different

style, but not less

artistic, are the six

chorales which Bach

published in 1746 with Joh.

Georg Schübler’s

publishing house, Zella, in

the Thuringia Forest. These

are not original

compositions, but

transcriptions of earlier

cantata themes for the

organ. We know the origins

of five of them, and they

are missing only as regards

the second piece. One cannot

refer to them even as

arrangements, that is to

say, as genuine

transpositions; for Bach

used the movements, without

changing the key,

practically note for note in

the new edition.

Nevertheless, if one did not

know the original pattern,

hardly anybody could detect

the fact of the arrangement

from the works themselves:

an indication that during

Bach’s time the

corresponding movement

forms-in this case the trio

and quartet movement - and,

with all due regard to the

peculiarity and tonal range

of the instruments in

question, were in principle

capable of transcription.

The six settings emanate

from cantatas out of the

"Choralkantaten-Jahrgangs”

composed 1724/25 and

subsequent supplements to

it. The first piece “Wachet

auf, ruft uns die Stimme”

(BWV 645) is the second

movement of the cantata 140

of the same name. The third

(BWV 647) is in cantata 93

“Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt

walten”, namely as a duet to

the verse “Er kennt die rechten

Freudenstunden”. The fourth

(BWV 648) also originally a

vocal duet, comes from

cantata 10 “Meine Seele

erhebet den Herren”. It is

used there for the verse “Er

denket der Barmherzigkeit”.

The fifth piece “Ach bleib’

bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ”

(BWV 649) originates from

the Easter cantata “Bleib

bei uns, denn es will Abend

werden” (canata 6). The last

one (BWV 650)

belonged to the text “Lobe

den Herren, der alles so

herrlich regieret” in

cantata 137 “Lobe den

Herren, den mächtigen

König

der Ehren". It is not clear

why Bach

assigns the organ version to

the less known advent song

“Kommst du nun, Jesu, vom

Himmel herunter”. The six

pieces at the same time

demonstrate various movement

possibilities: trio movement

with three thematic

independent voices in Nos. 1

and 6; with two imitating

voices in No. 2; with three

independent voices,

developed however from the

cantus firmus, in No. 5. A

quartet movement with two

imitating voices in No. 3,

and with three imitating

voices in No. 4. The fact

that the settings in the

cantatas in some cases apply

to other text verses shows

that the immediate linking

of the musical movement to

the text is only one partial

aspect, but not the main

principle of this music. In

the cantata setting, on

which the first piece is

based, the contrapuntal

discant voice is played by

the violins and viola in

unison. It illustrates to

begin with the appropriate

text “Zion hört

den Wächter

singen” - a joyfully

restrained, mystic wedding

song. In the organ version

the movement is likely to be

associated, and more

strongly registered, with

the first verse “Wachet auf,

ruft uns die Stimme” - an

example of the organist’s

possibilities of giving

prominence to the diverse

character of the individual

hymn verses.

by Georg

von Dadelsen

English

translation by

Frederick A. Bishop

*

This critical and complete

stylistic survey of Bach’s

organ works is the second

part of an essay the first

par: of whidi appeared in

the first edition of the

"Organ Works". It is

followed by the above

article and will be

continued by further

releases of Bach’s "Organ

Works".

|

|

|

Johann

Sebastian Bach - DAS

ORGELWERK

|

|

|

|