|

|

1 CD -

4509-97466-2 - (c) 1995

|

|

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9545-A - (p) 1969 |

|

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9482-A - (p) 1966 |

|

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9582-A - (p) 1971 |

|

| 1 LP -

SAWT 9589-B - (p) 1973 |

|

| 1 LP -

6.42365 AW - (p) 1979 |

|

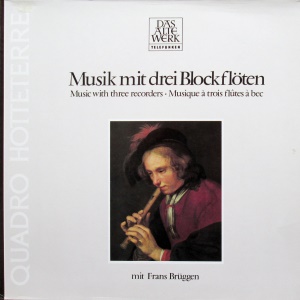

| FRANS BRÜGGEN

EDITION - Volume 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

| EARLY BAROQUE RECORDER MUSIC |

|

|

|

|

|

| Jacob

van Eyck (1589/90-1657) |

|

|

| 1. Batali -

tenor recorder - from "Der

Fluyten Lust-Hof", Vol. II,

Amsterdam 1649 |

4'

40" |

|

| 2. Doen Daphne

d'over schoone Maeght -

descant recorder - from "Der

Fluyten Lust-Hof", Vol. I,

Amsterdam 1646 |

9'

04" |

|

| 3. Pavane

Lachryme - descant recorder

(four figurations on John Dowland's

Pavan Lacrimae) - from "Der

Fluyten Lust-Hof",

Vol. II |

2'

16" |

|

| 4. - Variat[ie] 1 |

2'

15" |

|

| 5. - Variat[ie]

2 |

3'

42" |

|

| 6. - Variat[ie]

3

|

2'

06" |

|

7. Engels

Nachtigaeltje - descant

recorder - from "Der

Fluyten Lust-Hof", Vol. I

|

5'

42" |

|

|

|

|

| Girolamo

Frescobaldi (1583-1643) |

|

|

| 8. Canzon per

Canto solo e Basso continuo "La

Bernardina" - descant

recorder, organ and violoncello -

from "Il primo libro delle

canzoni", Rome 1628 |

3'

24" |

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni

Paolo Cima (c.1570, fl until 1622) |

|

|

| 9. Sonata in D

- tenor recorder, organ and

violoncello - from "Concerti

ecclesiastici", Milan 1610 |

4'

10" |

|

| 10. Sonata in

G - tenor

recorder, violoncello,

organ - from "Concerti

ecclesiastici" |

4'

10" |

|

|

|

|

| Giovanni

Battista Riccio (fl 1609 - 1621) |

|

|

| 11. Canzon a 4

in A - descant, treble and

tenor recorder, violoncello and

organ |

4'

10" |

|

| 12. Canzon in

A "La Rosignola" Pian e

Forte - two descant recorders,

tenor recorder, violoncello and

harpsichord |

2'

54" |

|

|

|

|

| Samuel

Scheidt (1587-1654) |

|

|

| 13. Paduan a 4

in D - Treble, tenor and

bass recorder, violoncello and

organ - from "Paduana,

galliarda, courante,...",

Hamburg 1621 |

6'

15" |

|

|

|

|

| Anon. |

|

|

| Sonata in G

- three

descant recorders,

violoncello and

harpsichord (c. 1620,

German or Polish) |

2'

38" |

|

| 14. Moderato |

0'

40" |

|

| 15. Andantino |

1'

12" |

|

| 16. Allegretto |

0'

46" |

|

|

|

|

| Frans Brüggen, recorder |

|

| Anner Bylsma, violoncello

(8-10) |

|

| Gustav Leonhardt,

organ (8-10) |

|

Kees Boeke, recorder

(11-16)

|

|

| Walter van Hauwe,

recorder (11 -6) |

|

| Wouter Möller, violoncello

(11-16) |

|

Bob van Asperen,

organ (11, 13) & harpsichord (12,

14-16)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

-

Bennebroek (Olanda) - aprile &

maggio 1969 [1-2]

-

Doopsgezinde Kerk, Amsterdam

(Olanda) - gennaio &

novembre 1971 [7]

-

Amsterdam (Olanda) - giugno 1972

[8-10]

- Doopsgezinde

Kerk, Haarlem (Olanda) - luglio

1979 [11-16]

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Engineer |

|

Wolf

Ericson [1-2] - Heinrich Weritz

[8-11]

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

- Telefunken

"Das Alte Werk" - SAWT 9545-A -

(1 LP) - durata 41' 45" - (p)

1969 - Analogico [1-2]

-

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" -

SAWT 9482-A - (1 LP) - durata

48' 01" - (p) 1966 - Analogico

[3-6]

- Telefunken

"Das Alte Werk" - SAWT

9582-A - (1 LP) - durata 52'

43" - (p) 1971 - Analogico

[7]

-

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk"

- SAWT 9589-B - (1 LP) -

durata 40' 54" - (p) 1973

- Analogico (8-10)

-

Telefunken "Das Alte

Werk" - 6.42365 AW - (1

LP) - durata 39' 49" -

(p) 1979 - Analogico

[11-16]

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Teldec

- 4509-97466-2 - (1 CD) - durata

58' 32" - (c) 1995 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

In

the early years of the 17th

century when instrumental

music was increasingly

breaking free from its vocal

models and developing its

own independent forms, the

terms “sonata” and “canzona”

were initially

interchangeable. Even as

late as 1637

a collection of instrumental

works by Tarquinio Merula

was published in Venice

under the title Canzoni

overo [or] Sonate.

Michael Praetorius attempted

a more detailed definition

in his Syntagma musicum

of 1618,

in which he discussed the

newest and most modern music

of his age: "In

my own view, however, this

is the difference,

namely, that sonatas are

set in a particularly

solemn and magnificent style

in the manner of a motet,

whereas canzonas, with their

many black notes, pass by

briskly merrily and

swiftly."

Girolamo Frescobaldi's

Canzona (in the edition of

the full score published in

Rome in 1628 it bore the

title “La Bernadina”)

certainly contains plenty of

"black

notes" and elaborate

passagework

especially towards the end.

The numerous adagio

interpolations are a modern,

canzona-based element,

whereas the imitative

part-writing reflects the

more conservative

compositional style

associated with the motet. In

consequence, the present

work is not exactly

representative of the

canzona an narrowly defined

by Praetorius.

In

Giovanni Battista Riccio's

Canzona, “La Rosignola”,

contrapuntal passages are

similarly contrasted with

dancelike episodes and with

soli and echo passages

(“Pian e Forte”) between the

two descant recorders. The

result is a piece which,

thanks to its use of

contrast and its interplay

between rhythmic and dynamic

elements, "passes

by merrily and swiftly".

These same characteristics

are also found, at least in

part, in an anonymous

Canzona dating from around

1620 and probably the work

of a German or Polish

composer living in Breslau.

Very little is known about

Riccio’s life, except that

he was appointed organist of

the Confraternita di S

Giovanni Evangelista in

Venice in 1609. In

the case of Giovanni Paolo

Cima, we can at least say

that he was organist at S

Celso in Milan and that in

addition to being a prolific

composer of instrumental

music, he also concerned

himself with the theory of

counterpoint, a concern that

found practical expression

in his Sonata in G minor, in

which descant and bass are

imitatively conceived. (A

similar feature had been

found in Frescobaldi's

Canzona.) Cima's Sonata is

further notable for the fact

that the initial theme is

taken up again and reworked

several times in the course

of the piece.

In

keeping with contemporary

musical praxis, all these

works (including Scheidt’s

Pavan) can be played on a

variety of different

instruments according to the

performers’ own discretion.

(In

his 1628 edition of "La

Bernadina", for example,

Frescobaldi writes "Violino

over Cornetto, come stà".)

Only

in the case of the pieces

from Jacob

van Eyck’s Der Fluyten

Lust-Hof of 1646 is

such discretion out of the

question, since all were

clearly written for the type

of recorder that van Eyck

himself appears to have

played. In 1648 he received

a pay rise of 20 thalers

from the Utrecht Town

Council for “entertaining

passersby in the churchyard

[at St John's]

by playing on his little

recorder”. His works are

based on sacred and secular

melodies wellknown in his

day and ornamented with a

series of variations. They

demonstrate the high

technical level attained by

recorder players in the

early years of the 17th

century.

Christian

Müller

·····

A brief

history of the

recorder

4.

The recorder in the 18th

century

The

first half of the 18th

century marked the

golden age of the

recorder as a solo

instrument. The descant

and treble instruments

were particularly

popular, hence the fact

that more of these two

types have survived than

of the tenor or bass

members of the family.

The most important

distinguishing features

of the Baroque recorder

are to be found in the

scaling of the tube and

the shape of the

windway. Most Baroque

instruments are in three

sections and elaborately

carved; mouthpiece and

rings are often of ivory

for aesthetic effect.

The holes are conically

drilled, wider on the

outside, narrower on the

inside, allowing the

player to produce a more

individual attack

without affecting the

pitch.

The Baroque treble

recorder generally has a

range of f' - g"/a'",

a range achieved by a

complex relationship

between its cylindrical

and conical dimensions

and by a complicated

system of fingering.

(The windway is

slightly curved and

conical, with the

distance from the end

of the windway to the

labium or lip being of

particular

importance.) The

descant recorders used

in schools today have

considerably

simplified bores and

windways; the sound is

far more monotonous,

the attack duller. Instruments

built in the old way

produce a more vibrant

sound with fewer

overtones. Moreover,

each tone and semitone

has its own colour, a

phenomenon that has

been lost from modern

wind instruments.

Recorder makers of the

18th century used

European boxwood by

preference, although

well-to-do customers

often commissioned

flutes of pure ivory

or with ivory

decorations, sometimes

even with a

tortoiseshell case. As

amateurs, such clients

no doubt played their

precious instruments

less frequently than

professional

musicians, who could

presumably afford only

the usual wooden

recorders. This may

explain why such an

extraordinarily large

number of recorders

has survived from the

18th century made

solely or partly of

ivory.

National

styles: the Low

Countries (I)

When Richard

Haka moved from London

to Amsterdam in around

1650, there were few

indications that he

was destined to become

Amsterdam's first and

most famous maker of

wind instruments. His

earliest instruments

date from the 1670s.

An advertisement of

1691 describes him as

a maker of “flutes,

oboes, bassoons and

military shawms”. At

this time the city’s

economy was enjoying

something of an

upturn, a prosperity

reflected in the

widespread private

cultivation of music

among the merchant

classes. Among Haka’s

surviving instruments

are two descant

recorders of

granadilla with ivory

rings (one of them is

in Frans Brüggen's

private collection and

may be heard in track

4). They are somewhat

old-fashioned for

their period, with a

tube made of two

sections and a double

hole for the little

finger. They have a

refined and attractive

sound relatively high

in overtones.

Peter

Holtslag

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|