|

|

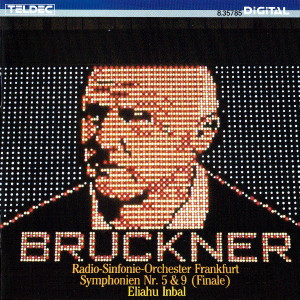

2 CD's

- 8.35785 ZA - (p) 1988

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 5 B-dur - Originalfassung |

70' 31" |

|

Compact disc 1

|

48' 19" |

|

-

Introduction: Adagio · Allegro

|

19' 43" |

|

| -

Adagio: Sehr langsam |

14' 41" |

|

| -

Scherzo: Molto vivace (schnell) ·

Trio: Im gleichen Tempo |

13'

45" |

|

| Compact

disc 2 |

43' 20" |

|

| -

Finale: Adagio · Allegro moderato |

22' 22" |

|

|

|

|

| Finale

der 9. Symphonie d-moll -

Rekonstruktion von Nicola Samale

& Giuseppe Mazzuca |

|

|

| -

Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell |

20' 44" |

|

|

|

|

| Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester

Frankfurt |

|

| Elihau Inbal,

Leitung |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Alte

Oper, Frankfurt (Germania) -

ottobre 1987 (5) & settembre

1986 (Finale 9)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Engineer |

|

Jeinz

Henke - Wolfgang Mohr - Hans

Bernhard Bätzing / Michael

Brammann - Detlef Kittler (HR)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Teldec

- 8.35785 ZA - (2 CD's) - durata

48' 19" | 43' 20" - (p) 1988 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Coproduktion

mit dem HR, Franfurt/Main.

|

|

|

|

|

Bruckner’s Fifth

Symphony, of which

only one version exists, is

probably to be seen as a

résumé of his second period

of composition, which ended

with symphonies nos. 1 - 4.

These years from 1868 to

1876 (Bruckner completed the

first written version of the

Fifth on 16th May 1876) were

marked by the march through

the institutions of

bourgeois Vienna and the

struggle for a teaching post

at Vienna University, which

culminated in Bruckner’s

initially being awarded an

“unpaid temporary position

to teach harmony and

counterpoint”. Eduard

Hanslick, the faculty member

responsible, has been forced

into the role of villain of

the story in Bruckner

literature, but today, when

we know all the

circumstances, he has been

rehabilitated: even today,

it would not be possible to

create a Professorship for

Composition at the

university.

There can be no doubt that

the Fifth Symphony as a

whole makes reference to

Anton Bruckner’s personal

situation, It “differs from

the author’s other

symphonies in its almost

obbligato polyphonic style

and an exceptional wealth of

contrapuntal art”, as Josef

Schalk observed in the

concert program of 20th

April 1887. Schalk and one

Professor Zottmann played

the work, which did not

receive its orchestral

premiere until 1894 in Graz,

on two pianos - a venture

that, if one is to believe

contemporary accounts, did

no great credit to its

participants. “Bruckner gave

Schalk and Zottmann a

dreadful time”, according to

the diary of Friedrich

Klose. Yet the musical

concept is perfectly clear.

The main model is

Beethoven’s Ninth, which in

the finale leads to the most

obvious analogy to a

historic work that Bruckner

ever produced. The themes of

the preceding movements of

the symphony are cited

according to Beethoven’s own

scheme.

This constructivistic model

also applies to the choice

of themes. The second theme

of the first movement is the

basic structure that is

taken up again in the

subjekt of the adagio as

well as in the liberal

thematic parallels of the

scherzo. The theme of the

finale, which is continued

in the fugal subject,

likewise comes from the same

design.

The conclusion of the

symphony with its resumption

of the main subject must be

seen as an equally clear

reference to the

constructivistic unity.

The treatment ofthe tremolo

within the framework of the

Fifth Symphony is also

resumptive in nature. It not

only alludes to the opening

of Beethoven’s Ninth (with a

downward jump of a fifth),

but also presents every

different form of the

tremolo developed in the

symphonies so far: the

symphonic-dramatic tremolo

of the First Symphony and

the development tremolo of

the Third, the echo tremolo

of the Second and the

formative tremolo of the

Fourth Symphony. Bruckner’s

varying timbre tremolo, a

pendant to the organ’s

tremolo stop, even makes a

thematic contribution in the

first

movement, where a new timbre

is required, after the

numerous attemps to forge a

theme, to constitute the

main subject. Just

as the tempo relation

adagio-allegro points

clearly to the model of

Viennese Classicism right at

the beginning of the first

movement, the finale is

almost metrically struct

ured, despite its colossal

length and the fugue on four

themes. The key number is

the 30 bars of the

introduction, and every

section that follows opens

with a multiple thereof:

logical balance as the heir

of Classical order. It is

quite possible that this

formal strictness and

deliberate look back to

earlier models have

something to do with the

problem of Bruckner’s

academic career at the

university and with the

subjects that he had to

teach. One can imagine that

Bruckner, driven by the idea

of teaching counterpoint,

now wanted to prove to

himself and the rest of the

world what he was capable of

in this field. He does this

’in modo antico’, which may

have been a result of his

understanding of the

academic world and perhaps

of the academic reality of

Vienna University. Offended

by the rejections that were

actually well substantiated

in formal terms, Bruckner

may not have realised that

in the art historian Rudolf

von Eitelberger and the

Professor for the “History

and Aesthetics of Music”,

Eduard Hanslick, he had

partners who were very much

his equals. But the composer

did know to whom thanks was

due for his first position:

Kard Edler von Tremayr, the

Minister of Arts and

Education at the time. It

was to him that Bruckner

dedicated the Fifth

Symphony.

The unfinisched finale

of Bruckner's Ninth

Symphony seems to exercise a

strong attraction on

musicologists and conductors

alike: since Alfred Orel’s

publication of the sketches

in 1934, no less than six

attempts have been made to

present the symphony’s

conclusing fragment, or its

reconstruction, to the

public.

This pursuit of the missing

finale began in 1940, when

Hans Weisbach wanted to give

the fragment, orchestrated

by Fritz Oeser, its first

performance in Leipzig.

Eight years later, Hans

Ferdinand Redlich and Robert

Simpson completed a piano

transcription of the Ninth

Symphony. The Austrian

conductor Ernst

Maerzendorfer attempted a

reconstruction in 1969, and

in 1974 Hans Hubert Schönzeler

presented his

instrumentation of the

fragment in London. At the

beginning of the 1970s, the

Italian musicologists Neill

and Gastaldi had tried to

make something of Bruckner’s

sketches, while Peter

Ruzicka accompanied his 1977

Berlin radio production with

a detailed commentary. The

most recent attempt was made

between 1983 and 1985 by the

Italian musicologists Nicola

Samale and Giuseppe Mazzuca,

who claim that the result of

their research not only

reproduces the finale of the

symphony in the composer’s

spirit, but that it may well

correspond for the most part

to Bruckner’s intended

instrumentation.

Samale and Mazzuca took as

the basis for their work all

the scores, both vocal and

instrumental, that Bruckner

completed in the last 12 -

15 years of his life, the

sketches of the last

movement that were

deciphered and published by

Alfred Orel in 1934, and the

surviving sketches of the

Ninth Symphony’s three

finished movements, which

were likewise published by

Orel. Where Orel had already

tried to arrange Bruckner’s

drafts and sketches so that

at least the intended

structure of the last

movement could be made

out, Samale and Mazzuca

placed their bets on the

establishment of an

analogy method. Their

comparison of the sketches

and the finished score for

the first three movements

was dictated first

and foremost by their

search for an analogical

principle. Accordingly,

they had to make use of

nearly all the sketchbook

pages, unlike Orel, and,

straitjacketed by their

analogy method, were

obliged to arrive at some

kind of blueprint plan for

the whole work. This means

that in Samale and

Mazzuca’s reconstruction,

the whole fourth movement

is 707 bars long: 180 bars

of complete drafted score

from Bruckner’s hand, 260

bars of unfinished draft

(string parts and

important wind motifs),

120 bars of sketches up to

the end of the reprise and

34 bars of sketches to the

development epilogue. This

leaves 113 bars of freely

added material; for the

coda, the two

musicologists considered

giving a central role to

the ostinato motif from

the Te Deum that appears

at the end of the

exposition. As always with

attempts to complete or

reconstruct music - this

is often the case with the

editing of source material

in manuscript form, too -

it is possible to conduct

a bar-by-bar

investigation, arriving at

different results and thus

initiating those

far-ranging discussions

that have become a ritual

feature of nearly every

complete edition and its

practical realisation.

Another approach, however,

is to pose fundamental

questions of principle, to

consider whether

reconstruction is

justified at all. A clear

dividing-line can then be

drawn between completion

and consenvation, as is

done in the restoration of

old paintings

or sculptures.

Samale and Mazzuca decided

in favour of completion,

and - if one reads the

introduction to their

“Completamento del finale”

carefully - have produced

thoroughly sensible

arguments for their work:

sensible in terms of

harmonics and

part-writing, and

relatively logical for the

expert on 19th century

composing theory. One

aspect they neglected,

though, was the special

nature of the composer

Anton Bruckner. Bruckner’s

musical lot was not an

easy one, and this gave

rise to the controversy

surrounding the different

versions that has

continued to the present

day. The difficulties were

spawned by the composer’s

neurotic desire for

stylistic perfection. This

can be traced at least in

part back to three basic

factors: Firstly, he was

not able to start

composing as he wanted

until the age of 40.

Secondly, he wanted to

hold his own alongside the

leading composers of his

time - he longed to equal

the musical authorities of

Vienna, and was haunted by

Bayreuth and the twin

geniuses Wagner and Liszt.

Last of all, there was his

desire to mould his

improvisatory,

organ-derived musical

thinking into a valid form

that would satisfy his own

exacting standards and

bring applause from

concert audiences. The

result of this neurotic

attitude was the continual

correction and improvement

of works he had already

finished, and of course

the dilemma of the

different versions, whose

relative merits are still

a source of argument for

musicologists and

music-lovers alike.

Quite unlike Süßmayr’s

completion ofthe Mozart

Requiem, for instance,

there is no inherent logic

that can be followed

through in Bruckner’s

works. This logic, in the

sense of musicological

causality, has already

proved a failure so far

with the versions

completed by Bruckner

himself and forces the

serious music researcher

to consider only what came

from Buckner’s own pen,

rigorously disregarding

every other addition and

alteration. For Bruckner’s

compositional thinking may

have been all-embracing in

the sense of projecting an

idea, but he did not think

in detailed structural

terms, as Mozart did. Thus

for Bruckner

the writing process was in

the final event the moment

in which the music was

created, crossing-out or

glueing-over represented

its erasure, as if the

notes now replaced had not

existed, and the periodic

counting which is

repeatedly mentioned was a

kind of final check after

fixing. A far cry from

Brahms and probably from

Mahler too, this kind of

work construction eludes

the application of a

progressive, inherent

logic - unless of course

the composer’s own hand

creates with the

writing-down of his ideas

the causality that

the researcher or

interpreter subsequently

feels to be ’Brucknerian

logic’. In this connection,

it is striking that, despite

the discrepancies between

Bruckner’s first

and second versions, this

Brucknerian logic seems to

be quite comprehensible in

each case, although

completely different results

are achieved with almost the

same material. Thus, it has

to be stated that -

irrespective of whether

completion is accepted as

avalid activity - in

Bruckner’s case completions

can only reflect the ideas

of the individual author. On

no account can the author

claim to have reconstructed

Bruckner’s actual ideas.

Accordingly, Alfred Orel was

without

a doubt right in not daring

to arrange the existing

sketches in a finale,

definitive order. The fact

that the sketches were

published certainly

represented a challenge to

musicologists to ’set to

Work’ on them. But Bruckner

himself would with equal

certainty not have agreed to

their publication, since,

quite unlike some other

composers, he accepted only

what he had personally put

to paper - and had given

a specific designation - as

the expression of his

artistic intent.

Manfred

Wagner

Translation:

Clive R. Williams

|

|

|