|

|

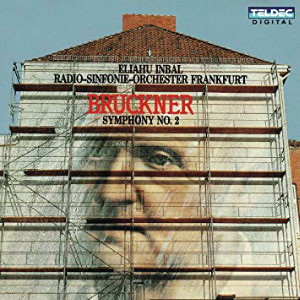

1 LP -

6.44144 AZ - (p) 1988

|

|

| 1 CD -

8.44144 ZK - (p) 1988 |

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 2 c-moll - Revidierte

Fassung von 1877 |

61' 34" |

|

| -

Ziemlich schnell |

20' 01" |

|

| -

Feierlich, etwas bewegt |

16' 11" |

|

| -

Scherzo: Schnell - Trio: Gleiches

Tempo |

7' 13" |

|

-

Finale: Mehr schnell

|

17'

51" |

|

|

|

|

| Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester

Frankfurt |

|

| Elihau Inbal,

Leitung |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Alte

Oper, Frankfurt (Germania) -

giugno 1988

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer /

Engineer |

|

Wolfgang

Mohr - Hans Bernhard Bätzing /

Martin Fouqué

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Teldec

- 6.44144 AZ - (1 LP) - durata 61'

34" - (p) 1988 - Digitale |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Teldec

- 8.44144 ZK - (1 CD) - durata 61'

34" - (p) 1988 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Co-Produktion

mit dem HR, Franfurt.

|

|

|

|

|

“I

only write music, and not

reviews, so that the Lord

has no cause to say to me:

‘Why haven’t you produced

anything my fellow? I gave

you talent to edify and refine

mankind, to fill men with

lofty thoughts, and you

have produced nothing!"

Anton Bruckner 8th May

1893, during the interval

at a university lecture.

Bruckner was actually

anything but unproductive:

he worked tirelessly,

despite moments of deep

resignation, despite all the

disappointment that resulted

from the poor reception of

his music. But his

application was of little

use to him in this life:

Anton Bruckner was a

tragically unrecognised

genius, and the fate

initially suffered by the

fruits of his life’s work

reflects an age

unfortunately rich in

musical philistines.

How much would have been

lost to the world, had it

not been for Bruckner’s

unshakeable will to compose!

As it was, he lived in the

consciousness of a mission

on which the final judgment

would not be passed by the

critic Hanslick or by his

fellow composer Brahms.

“Bruckner? An utter fraud!

He’ll be forgotten within a

few years of my death.” -

thus Brahms to the Austrian

critic Richard Specht in the

spring of 1897. Bruckner

himself, who died a year

before the Hamburg

composer's ungenerous fit of

anger, had already remarked

polemically some years

earlier (8th January 1892):

“They called Beethoven the

musical pig in his time, and

said he should be locked up

in an asylum. I think to

myself: You just carry on

writing, just look straight

ahead. I’ll

long since be in my grave by

the time Hanslick

understands..."

Anton Bruckner stood alone,

as his favourite pupil Franz

Schalk commented, “without

support from anyone, truly

helpless, yet unshakeable in

the humble belief in Eternal

God, in the proud, almost

heathen belief in himself

and the glory of his music.”

Bruckner was in no way an

urbane man, he was the

simple product of a

money-oriented, secular,

bourgeois era - yet in some

mysterious fashion, he

created musical - urbane! -

culture of lasting, global

status from a unique

symbiosis of naive rural

piety and gigantic inner

musical visions. It was

Bruckner, and not Brahms,

who carried on the Austro-German

symphonic tradition after

the death of Robert Schumann

in 1856: both Brahms and

Bruckner came to symphonic

composition late in life,

and Bruckner wrote his First

Symphony when he was almost

42 (1865/66) - some ten

years before Brahms

completed his ’First’ (the

'Tenth' according to Hans

von Bülow!) in

1876 at the age of 43.

The Second Symphonie in C

minor was composed at a time

when Bruckner had found

international recognition -

albeit as an organ

improviser rather than a

composer - which gave him

enormous inner momentum: in

1869 he played in Paris

(Notre Dame), and in 1871 he

had taken part in a

competition in London on the

new organ in the Royal

Albert Hall that had been

built for the World

Exhibition. After his return

to Vienna, Bruckner began

work on his Second Symphony.

He composed the first

version of the work between

11th October 1871 and 11th

September 1872, and gave the

symphony its first

performance in this form on

26th October 1873 in Vienna.

He dedicated this first

version to the Philharmonic

Society. On the advice of Johann

Herbeck, Bruckner reworked

the symphony, and this

revised version was first

performed on 20th February

1876. Finally, in the

following year, a third and

last version appeared: the

composer dedicated it to

Franz Liszt, whom he had met

at the singers’ festival in

Pest in 1865.

It is interesting to observe

how Bruckner relies on the

principle of the 'talking

pause’ in his Second

Symphony, the considerable

structural power of the

General Pause. (Thence the

nickname ’Pause Symphony’.)

The contrapuntal and the

dispositive precision work

are intensified in relation

to the First Symphony; the

principle of the composer

quoting himself is found in

the Adagio, that refers to

the Benedictus, and in the

finale, which refers to the

Kyrie of the F minor Mass.

Furthermore, two other

features of Bruckner’s music

make their first appearance

here: firstly, the

embellishment of one step of

the scale by the upper and

lower leading notes, and

secondly - taken over from

Wagner - , mixed rhythm

within one bar.

Bruckner’s Symphony no. 2

has four movements. The

first in the principal key

of C minor is in sonata

form, with three thematic

groups in the exposition,

epilogue and epilogue-coda,

a development section,

reprise and coda. The second

movement in A flat major is

a sonata form without the

development section. The

third, one of Bruckner’s

most extraordinary scherzi,

is in the key of C minor

with a C major trio, while

the finale, which is

governed by C major and

minor, is once again a

richly varied sonata

structure with an exposition

containing three thematic

groups, epilogue and

epilogue-coda, plus

development, reprise and

coda to the movement as a

whole.

The 'original version’ was

not published until 1938,

when it was brought out by

Robert Haas. It is based in

fact on the third version

dating from 1877 - this,

however, also uses elements

from the first version of

1871/72, thus eliminating

the 139-bar cut which would

have altered the proportions

of the entire work. In

addition, the

instrumentation, dynamics

and phrasing were adopted

from the first version. This

seems sensible, for, as

Bruckner rightly commented

in answer to suggestions for

shortening his F minor Mass

(1893): “I’ve

already kept it short. If I’d

written down everything I

thought of to the greater

glory of God, it would have

been even longer.”

Knut Franke

Translation:

Clive R. Williams

|

|

|