|

|

1 LP -

2533 134 - (p) 1973

|

|

| 4 CD's -

439 964-2 - (c) 1992 |

|

| WIENER TÄNZE DES

BIEDERMEIER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Viennese Dance dating from

the Biedermeier Period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Michael Pamer

(1782-1827) |

Walzer in E-dur (1818) |

Ersdruck (1818).

Cappi & Diabelli, Wien.

Expl. Stadtbibliothek Wien |

|

4' 00" |

A1 |

| Ludwig van

Beethoven (1770-1827) |

Tämze

"Mödlinger Tänze", Nr. 1-8,

WoO 17 (1819) |

Erstausgabe

(1907). Breitkopf & Härtel,

Leipzig. Ed. H. Riemann

(Part.-Bibl. 2058) |

|

13' 57" |

A2 |

| Ignaz

Moscheles (1794-1870) |

Deutsche Tänze

samt Trios und Coda (1812) |

Ms. Wien,

Österreichische

Nationalbibliothek, Sm 2240 |

|

8' 21" |

A3 |

| Franz Schubert

(1797-1828) |

5 Menuette mit

6 Trios, D. 89 (1813) |

Schubert-GA,

Serie II, Nr. 8 |

|

13' 30" |

B1 |

| Franz Schubert |

4 komische

Ländler, D. 354 (1816) |

Schubert-GA,

Supplement |

|

2' 13" |

B2 |

| Anonym |

Linzer Tanz.

Wiener Polka (um 1820) |

Universal

Edition Wien. "Rote Reihe", Bd.

3 (UE 20 003). Ed. W. Deutsch |

|

3' 32" |

B3 |

| Joseph Lanner

(1801-1843) |

Ungarischer

Galopp in F-dur (um 1835) |

Ms. Wien,

Stadtbibliothek, MH 2255 |

|

2' 19" |

B4 |

|

|

|

|

| ENSEMBLE

EDUARD MELKUS |

| -

Eduard Melkus, Spiros Rantos, Solovioline |

| -

Thomas Kakuska, Günther Schich, M.

Gomberti, Wilhelm Jordan, Reinhart

Strauß, E. Eichwalder, Prunella

Pacey, Lilo Gabriel, Violine |

| -

Lilo Gabriel, Viola |

| -

Martin Sieghart, Violoncello |

| -

Heinrich Schneikart, Kontrabaß |

| -

Karl Scheit, Gitarre |

| -

Werner Tripp, Barbara Müller-Haase,

Flöte |

| -

Manfred Kautzky, Günter Lorenz, Oboe |

| -

Alfred Prinz, Peter Schmidl, Horst

Hajek, Klarinette |

| -

Dietmar Zeman, Camillo Öhlberger, Fagott |

| -

Friedrich Gabler, Gernot Sonneck, Horn |

| -

Josef Hell, Josef Pomberger, Wilhelm

Kormann, Trompete |

| -

Josef Rohm, Posaune |

| -

Richard Hochrainer, Georg Wagner, Schlagwerk |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Palais

Schönburg, Vienna (Austria) -

10/12 aprile 1972 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Andreas Holschneider |

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Werner

Mayer

|

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Klaus

Scheibe |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

ARCHIV

- 2533 134 - (1 LP - durata 48'

15") - (p) 1973 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ARCHIV

- 439 964-2 - (4 CD's - durata 71'

35"; 70' 09"; 70' 42" & 72'

56" - [CD4 5-11]) - (c) 1992 - ADD

|

|

|

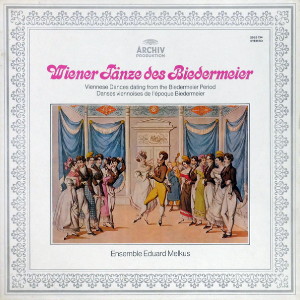

Cover |

|

Wiener

Biedermeier-Szenen: "Tanzmeister

Pauxel" oder "Faschingsstreiche".

Theatermuseum München |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Viennese Dance

dating from the Biedermeier

Period

“In Vienna in July there is a

real folk festival, if ever a

festival deserved the name. It

is given by and for the ordinary

people, and if anyone of higher

rank happens to join in, then

only in his role as a normal

citizen. This is the day when

the people of Brigittenau hold

their parish fair. In the

usually peaceful town uproar

prevails. Class distinctions

vanish; worthy citizens and

rough soldiers share in the

bustle... Those who come by

carriage climb down and mingle

with their brethren on foot; the

strains of distant dance-music

float overhead and are taken up

by cheering newcomers. And so

on, further and further, until

this generous harbour of

delights opens out, and woods

and meadows, music and dance,

wine and feasting, shadow-plays

and tightrope walkers, bright

lights and fireworks all blend

to become a true Eldorado, a

real piece of Paradise...” There

is no better picture of the

Viennese spirit during the

Biedermeier period than this

sketch by the Austrian novelist

Franz Grillparzer, taken from

his short story, Der arme

Spielmann.

In Austria Biedermeier

was that clearly defined period

between the Congress of Vienna

in 1815 and the year of the

Revolution, 1848, between the

end of the Napoleonic era and

the first attempts by the

bourgeoisie to wrest away some

of the privileges of the

all-powerful aristocracy. At

that time the old imperial city

of Vienna was still surrounded

by mighty fortifications beyond

which there were villages and

little towns in the midst of

pastureland and vineyards.

Vienna was still the musical

metropolis of the world, and

there was music everywhere - in

the theatre, in the churches, in

stately palaces, middle-class

homes and village taverns. In

all this, dance music was by no

means the worst off; it was not

considered in the least lowly,

and it was treated with respect

by the great masters as well as

by dozens of less famous

composers whose names have now

been forgotten.

In such an atmosphere it was

only natural that Franz Schubert

- one of the few great Viennese

composers who were actually born

in Vienna - played waltzes and

ländler on the piano, and that

he wrote them down. It was also

only natural that for his own

friends he composed minuets

scored for a string quartet; it

was customary at the time to

write them for a large orchestra

to be played in the ballroom.

The fact that they are

masterpieces is just another

extraordinary aspect of this

young man’s genius - at the time

he was just 16. The moods of the

late string quartets are already

evident here, and the formal

interweaving of minuets and

trios is a stroke of genius.

Minuets I, III and V each have

two trios, Minuets II and IV on

the other hand none at all; the

result is that when played in

sequence Minuets III and V seem

to become trios for the minuets

that precede them. By erasing

the contours of his

compositions, Schubert achieves

a remarkable effect of

concentration.

As he wandered with his friends

through the villages, Schubert

was constantly absorbing the

stock-in-trade of the local

music. A favourite setting was

for two violins and a small

double bass - the so-called

“Bassl”; occasionally the tonal

gap between these was filled up

by a guitar, and sometimes the

guitar took the bass’s place.

The “violinists from Linz” came

down the Danube to Vienna with

these instruments, and played

for dances there. In the

versions which have survived,

one can often still find the old

pairing of slow and fast dances

(as in the “Linz” dance). The

polka imported from Bohemia also

puts in an appearance, though

here in a Viennese version

(Viennese Polka). And when the

young Schubert writes four

“comic ländler” for two violins

he makes a good job of imitating

the manner of popular

music-makers.

Just as the nobility maintained

residences in the country for

the summer months, so the

wellheeled middle-classes liked

to have a house “in the

country”. The favourite

districts were just a few

kilometres from the city itself

in Heiligenstadt and Nussdorf;

Mödling and Baden were a day’s

journey away to the south. Those

without a country house would

rent rooms there and move out of

the city for the summer. The

great man from Bonn who had made

his home in Vienna also followed

this custom; during one of his

stays in Mödling, Beethoven

actually met the musicians for

whom he had written the

“Mödling” Dances in 1819.

Viennese folkmusic is often

scored for two clarinets as well

as two violins; in these dances

the clarinet dominates, though

the scoring also includes two

violins, a flute, a bassoon and

two horns. The idyllic mood is

strongly reminiscent of the Trio

from the Scherzo in the Eighth

Symphony.

One or two lesser composers also

achieved fame with some

brilliant compositions. The

music libraries in Vienna are

full of such works, and from

them we have chosen the German

Dances by Ignaz Moscheles. He

was born in Prague and was a

child prodigy as pianist and

composer. At the time of the

Congress of Vienna he was living

in the city, studying

composition under

Albrechtsberger and Salieri, and

appearing in his own concerts.

His German Dances exude the true

Schubertian spirit, and in their

tendency to modulate to the

minor and to make use of

third-relationships they show a

strong resemblance to Schubert’s

work. Right in the middle of the

turbulent coda there is, as a

finishing touch, a bell which

tolls twelve times (we find it

again as a charming touch in Die

Fledermaus) and the

nightwatchman’s song is invoked;

then the whole is rounded off in

a dashing finale.

A true product of the Viennese

outskirts was the tavern

violinist Michael Pamer, known

in his day as a great virtuoso.

He was active in teaching and

encouraging the younger

generation, to which Joseph

Lanner and Johann Strauss (the

Elder) belonged. Indeed it was

thanks to Pamer that the truly

“Viennese” waltzes became

accepted, and it was only on the

basis of his work that Joseph

Lanner, Vienna’s musical

darling, could produce his

gentle melodies which reveal the

very best aspects of Viennese

music of the time; even in the

guise of a Hungarian in the

Rakoczi March (The Hungarian

Galop) Lanner could not hide his

Viennese origins.

Looking back at this period over

one and a half tenturies, one

would like to enjoy its music in

its authentic form; it is

therefore reproduced here

without any retouching

whatsoever - markedly different

from the versions played by

modern dance bands, or those

“symphonic” effects produced by

our best orchestras. Here the

scoring is for a small group of

strings, the most usual way it

was heard then, and the original

instrumentation offers a natural

balance between strings and

wind.

E.

Melkus - W. Gabriel

|

|

|