|

|

1 CD -

8.557532 - (c) 2011

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 12

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

Duo

Concertant for Violin and Piano

(1932)

|

*

|

|

16' 31" |

|

|

-

Cantilène

|

|

3' 09"

|

|

1

|

|

-

Eclogue I

|

|

2' 25" |

|

2 |

|

-

Eclogue II

|

|

3' 07" |

|

3 |

|

-

Gigue |

|

4' 33" |

|

4 |

|

-

Dithyramb

|

|

3' 16" |

|

5 |

|

Jennifer

Frautschi, Violin | Jeremy Denk,

Piano

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sonata

for Two Pianos (1943-44) |

|

|

10' 54" |

|

|

-

Moderato

|

|

4' 24" |

|

6 |

|

-

Theme with Variations: Largo

|

|

4' 40" |

|

7 |

|

-

Allegretto

|

|

1' 49" |

|

8 |

|

Ralph van Raat,

Piano I | Maarten van Veen, Piano

II

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Requiem

Canticles (1965-66) |

|

|

15' 16" |

|

|

- Prelude

|

|

1' 17" |

|

9 |

|

-

Exaudi

|

°

|

1' 50" |

|

10 |

|

-

Dies Irae

|

°

|

1' 04" |

|

11 |

|

- Tuba Mirum

|

**/°

|

1' 16" |

|

12 |

|

-

Interlude

|

|

2' 56" |

|

13 |

|

-

Rex Tremendae

|

° |

1' 24" |

|

14 |

|

-

Lacrimosa |

*/° |

2' 08" |

|

15 |

|

-

Libera Me

|

° |

1' 17" |

|

16 |

|

-

Postlude |

|

2' 06" |

|

17 |

|

Sally Burgess,

Contralto* | Roderick Williams,

Bass** | Simon Joly Chorale°

Philharmonia Orchestra |

Robert Craft, Conductor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abraham

and Isaac: A Sacred Ballad for

Baritone and Chamber Orchestra

(1962-63) |

|

|

13' 45" |

18 |

|

David

Wilson-Johnson, Baritone /

Philharmonia Orchestra / Robert

Craft, Conductor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Élégie

for Solo Viola (1944) |

|

|

5' 18" |

19 |

|

Richard O'Neill,

Viola

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bluebird

Pas de Deux (Tchaikovsky /

Stravinsky, arranged 1941) |

|

|

5' 52" |

|

|

-

Adagio |

|

2' 19" |

|

20 |

|

-

Variation I: Tempo di Valse

|

|

0' 53" |

|

21 |

|

-

Variation II: Andantino

|

|

0' 49" |

|

22 |

|

-

Coda · Con moto

|

|

1' 51" |

|

23 |

|

Twentieth Century

Classics Ensemble°° | Robert

Craft, Conductor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TWENTIETH

CENTURY CLASSICS

ENSEMBLE °°

- Tara

O'Connor, Flute

- Steohen Taylor, Oboe

- Alan Kay, Stephen

Ziekinski, Clarinets

- Frank Morelli, Bassoon

- William Purvis, Horn

- Louis Hanzlikm John

Sheppard, Trumpets

- Michael Boschen, David

Taylor, Trombones

- Alex Lipowski, Timpani

- Sean Chen, Piano

- Lily Francis, Aaron

Boyd, Anna Lim, Laura

Frautschi, Cal Wiersma,

Violins

- Beth Guterman, David

Fulmer, Mark Holloway,

Lisa Steltenpohl, Violas

- Fred Sherry, Raman

Ramakrishnan, Hamilton

Berry, Cellos

Timothy Cobb, Gregg

August, Double

basses

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

Concert Hall,

SUNY, Purchase, New York (USA):

- 21 May 2008 (Duo Concertant)

Abbey Road Studio One, London

(England):

- 19 September 2005 (Sonata for

Two Pianos)

- 18 and 19 September 2005

(Requiem Canticles)

- 1 and 2 October 2007 (Abraham

and Isaac)

American Academy of Arts and

Letters, New York (USA):

- 19 Novembre 2005 (Élégie for

Solo Viola)

- 28 Ocotober 2008 (Bluebird Pas

de Deux)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Philip

Traugott

|

|

|

Engineers |

|

Tim

Martyn (Duo Concertant, Élégie for

Solo Viola, Bluebird Pas de Deux)

Mike Hatch (Sonata for Two Pianos,

Requiem Canticles, Abraham and

Isaac)

|

|

|

Editors

|

|

Tim

Martyn (Duo Concertant, Élégie

for Solo Viola,

Bluebird Pas de Deux)

Raphaël Mouterde (Sonata for Two

Pianos, Requiem Canticles,

Abraham and Isaac)

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557532 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 67' 36" | (c)

2011 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

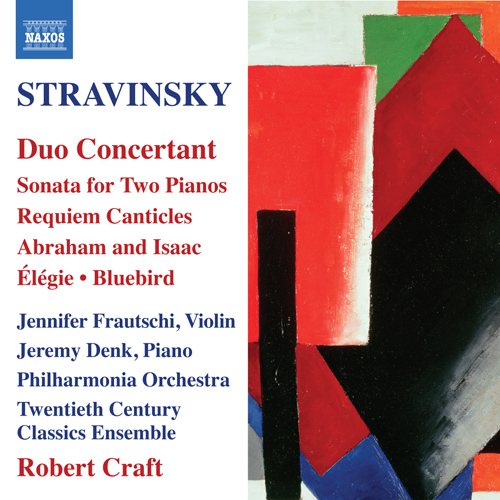

Cover |

|

Architectonic

Composition by Lyubov'

Sergeevna Popova (1889-1924)

(Private Collection / The

Bridgeman Art Library) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

|

The

acclaimed Naxos Robert Craft

Stravinsky Edition continues

with this fascinating album of

diverse pieces by one of the

20th Century’s iconic composers.

The Duo Concertant

reconciles the contrasting

timbres of violin and piano,

while the breezy Sonata for

Two Pianos, written in

America, draws on Russian

themes. The Requiem

Canticles was performed at

Stravinsky’s funeral, while the

‘sacred ballad’ Abraham and

Isaac is a dramatic and

moving retelling of the Old

Testament story. The Élégie

for solo viola is one of his

most affecting works, and Bluebird

is a loving arrangement for

chamber orchestra of excerpts

from Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping

Beauty.

Duo Concertant

Duo Concertant was

written between 27 December 1931

and 15 July 1932. Stravinsky

spoke freely about his composing

philosophy to interviewers

during his concert tours,

characterizing the first Eclogue

to a reporter in Oslo as a Kazatchok,

a Russian dance, and revealing

that after working on the first

trio of the Gigue he had

“jumped up from the piano and

danced and sung the “Glücklich

ist” refrain from Johann

Strauss’s Fledermaus.

The première was in Berlin on 28

October 1932.

The first recording of Duo

Concertant took place in

Paris on the 6 and 7 of April

1933, played by the composer and

Samuel Dushkin. Stravinsky told

an interviewer in Budapest that

“I have completed what could be

called a sonata for piano and

violin inspired by Virgil’s Georgics”.

It is athematic in the first

movement, which introduces the

instruments separately and

fragmentally, before bringing

them together, a reminder that

Stravinsky construes

“concertant” as meaning

“competition”. Throughout the

1920s he maintained that the

sound of strings struck in a

piano did not suit the sound of

a multiple group of strings

bowed, but he had reconciled

himself to mating the two in a

solo combination. The Cantilène

exhibits their distinctive

characteristics, the piano

producing tremolos on five

successive single pitches while

the violin plays nine phrases of

sixteenth-notes (semiquavers).

In truth, the title Cantilène

seems contradictory to the style

of the music which is song-like

only for moments in the violin

part but otherwise athematic.

No less puzzlingly, Stravinsky

referred to the first movement

as a perpetuum mobile,

whereas the term more aptly

describes the first Eclogue

and the Gigue. The

second half of the first Eclogue

recalls the Histoire du

Soldat in its changing

metres, staccato style, and

double-stopping in the violin

part. The second Eclogue,

the slow movement of the suite,

brings the two instruments

together playing the same dotted

rhythms and eighth-notes

(quavers) with a lovely melodic

interplay. Here Stravinsky

renounces his precepts about

competition and combat.

The inherent monotony of Gigue

rhythm is relieved by the

smoothest two-way metrical

modulation in all Stravinsky’s

music, moving from 6/16 and

12/16 metre to 2/8 and 2/4

metre, the first change also

being distinguished by the

doubling of the violin melody

with harmonic thirds. In the

latter part of the piece the

piano becomes the leading

melodic instrument, the

traditional piano accompaniment

figure being assigned to the

violin in a high register.

Dithyramb, the eloquent

peak of the Duo Concertant,

takes its place in the

succession of Stravinsky’s

apotheoses (Apollo, Le

Baiser de la Fée, and

later, Orpheus).

Sonata for Two Pianos

The Sonata for Two Pianos

was not commissioned and did not

at first assume a sonata form.

On 12 August 1942, Stravinsky

began to orchestrate a part of

the first movement of whatever

he was writing, which suggests

that he may have been

considering a proposal to

compose a film score. He resumed

work on the sketch on 9

September and added more

instruments, including trombone.

The third movement was composed

next, but his final intentions

are still unclear. The second

movement, which he did not begin

until more than a year later

(October 1943) - he was

interrupted to write Scherzo

à la Russe and the Ode

for Serge Koussevitzky’s wife -

resolves all doubts since it has

the title Theme with

Variations, and could only

be the middle movement of a

sonata. This composition

occupied him for five months and

required a full sheaf of

sketches. Readers familiar with

the score will be surprised to

learn that the original of the fugato

Variation is in F major (not G

major, as published).

Stravinsky scholars will be

tempted to conclude that Nadia

Boulanger, who was near him

during most of the composition,

had persuaded him that the long

lines of the music were more

suited to the two-piano

combination than to any

instrumental ensemble, though,

of course, he was quite capable

of making this decision himself.

After publication, Stravinsky

was proud to learn that Dimitri

Mitropoulos and Ernst Krenek had

performed the piece publicly in

Minneapolis. The opus became

popular and entered the

repertory of duo-piano teams

everywhere, including Gold and

Fizdale, and Babin and Vronsky.

The piece provided a happy

continuation of Stravinsky’s

development of a breezy,

lighthearted American style,

following the Circus Polka,

Norwegian Moods and Danses

Concertantes.

Ironically, the American piano Duo

consists largely of elaborations

on Russian themes. The Theme

with Variations movement

is based on No. 46 in a book

called Russian Ballads and

Folksongs that Stravinsky

found in a used bookstore in

Hollywood in the spring of 1942.

But apart from melody, the

extreme simplicity of line and

harmony shows a change in mood

and style that is absent from

Stravinsky’s earlier European

creations. For only one

distinction, the lines are

longer, the rhythms and metres

more simple, and the harmony

more transparent. Stravinsky,

then in his late fifties, was at

last free from his double life

and his need to provide for a

large congregation of relatives,

and to enjoy the climate and

other benefits (perhaps there

were some in the early 1940s) of

Southern California.

Requiem Canticles

Shortly after the première of

the Requiem Canticles at

Princeton, Stravinsky answered

an inquiry concerning the

origins of the piece: “I began

with intervallic designs that I

expanded into musical shapes

which suggested musical forms

and structures. The twofold

series was also discovered early

on while I was completing the

first musical trope, as was the

instrumental basis, the idea of

the triangulate frame of a

string Prelude, wind-instrument

Interlude, and percussion

Postlude. The overall design of

the piece is symmetrical, six

vocal movements divided at

mid-point by an instrumental

dirge.”

Stravinsky pasted his sketches

into a loose leaf notebook and

added photographs of people who

had died during the composition

of the work. Thus an obit of

Edgard Varèse that includes two

photos, clipped from The New

York Times on 8 November

1965, appears on a page facing a

sketch for two choral phrases of

the Exaudi. No connection exists

between the music and the

deceased, nevertheless, the

conjunction of this friend’s

death exposes an almost

unbearably personal glimpse of

Stravinsky’s mind during the

composition of the entire work.

It is enough to say that the

sketchbook preserves a diary of

his musical thoughts. Thus the Rex

Tremendae sketch reveals

that the pitches chosen occurred

to him a stage ahead of their

final groupings. The Tuba

Mirum sketch invites the

reader to plot the composer’s

thinking from a larval stage to

the final score. In one case,

the page devoted to Alberto

Giacometti, the pre-positioning

of which obviously inspired

Stravinsky to draw the slightly

wavering lines of a cross over

the photos of him, may have

inspired the music as well, but

that is only my speculation.

Another happening, this one from

the theater world, left its mark

on the composition. Stravinsky

saw the New York stage

production of Peter Weiss’s

play, Marat/Sade and was

inspirited by the incoherent

talk of the crowd scene to the

extent of using his chorus in a

parlando to suggest a

mumbled congregational prayer in

the background of his

penultimate movement, Libera

Me. The foreground here is

a rapid chant in measured

quarter notes (crotchets) sung

by a solo vocal quartet of

soprano, alto, tenor, and bass.

But on second thoughts,

Stravinsky did not want this

confusion of voices representing

a church congregation, but

desired instead to devise a

measured spacing of the spoken

chant by indicating boundaries

in which to limit the speeds for

each section of the spoken

words.

The choice of chords mixing

celesta, campane and vibraphone

in the Postlude was the

most daring concept in the

entire opus since Stravinsky had

never heard the three

instruments together, and since

all of the notes have to be

equally balanced in volume. The

celesta, of course, is the

highest in range and the campane

part is confined to the middle

of the treble clef. The

distribution of the vibraphone

pitches is the most precarious.

Every chord contains at least

one octave or unison. The

two-note vibraphone chords are

the widest in range, the

two-note campane chords are the

closest together, and the

celesta, which plays chords of

three to four notes, provides

the richest colour. No chord is

exactly repeated. Ingeniously,

Stravinsky introduces the second

chord of the second trope of

this trio with an appoggiatura

in all three instruments in

preparation for the appoggiatura

in the bass part of the piano in

the final three chords of the

piece. Here, the penultimate

chord is sounded twice which

functions as a preparation of

the final “chord of death”,

resolving the procession of

harmonics.

Abraham and Isaac

The Sacred Ballad for

Baritone and Chamber Orchestra

sets verses 1–19 of Chapter XXII

of the Book of Genesis,

in which God commands Abraham to

take his son Isaac into the land

of Moriah and sacrifice him.

After the journey is enjoined,

Abraham experiences a vision of

the place of sacrifice from

afar. The wood for the burnt

offering is gathered and Abraham

binds Isaac to the altar. God

recognizes Abraham’s willingness

to sacrifice his son. The ram is

caught and sacrificed instead of

Isaac. Abraham retires to

Beersheba.

Stravinsky worked from a Russian

transliteration of the Hebrew

text prepared by Isaiah Berlin,

who also provided him with a

guide to pronunciation and

accentuation. Additional

tutoring in pronunciation and

word setting from the composer

Hugo Weisgall, who was in Santa

Fe when Stravinsky began work on

the composition in the summer of

1962, should also be

acknowledged; Stravinsky

received Hugo Weisgall several

times in the La Fonda Hotel, and

a chart survives in his hand of

vowels and consonants and their

equivalent pronunciation in

English. Stravinsky entered both

the Latin-letter transcription

of the Hebrew text and the

English translation in his

manuscript, but the piece was

designed to be sung in Hebrew

only: the sounds of the words

and the music are inseparable,

the appoggiaturas, quasi-trills,

melismas, and other stylistic

embellishments unsuited to any

other language.

Completed in Hollywood on 3

March 1963, the score, dedicated

To the People of Israel,

is now in the Israel Museum,

Jerusalem. Theodore Kollek, the

Mayor of Jerusalem, wrote to

Stravinsky on 30 March 1965,

recalling a dinner in Hollywood

a few weeks before with the

Stravinskys and “our mutual

friends Isaac Stern, Grisha

Piatigorsky, and Bob Craft”,

asking him to give the

manuscript to the Israel Museum

on grounds that as compared to

the Los Angeles County Museum

“our setting is better,

overlooking as we do the

beautiful Byzantine Russian

Orthodox Monastery and the

eternal hills of the Land of

Abraham and Isaac”. But Kollek

had been given the wrong address

and his letter was returned to

him. When he wrote again, on 16

May, Stravinsky was

concert-touring and did not

receive the letter until 15

July, on which day he replied:

“The enclosed manuscript…is my

answer….I hope it will be not

long before we meet again. All

best, my dear friend….”

The instruments play alone only

in the introduction and in the

brief interludes that divide the

narrative into six sections,

each of them distinguished by a

progressively slower tempo. The

full orchestra is never employed

together. With the intention of

giving the words the highest

possible relief, Stravinsky

confined much of the

accompaniment to a single line

shared between and among

different instruments. The

second part of the narrative,

beginning with the words

“Abraham took two of his boys

with him”, is scored for a

single line of wind instruments,

which, at the words “Whereof

spoke to him God”, spreads to

two parts. Here and elsewhere,

the word of God related by the

angel of God, is accompanied by

strings only, at first by five

tremolo chords in the upper

register, a device that

Stravinsky had associated with

the voice of God in The

Flood, his Biblical opus

of the previous year. The next

section, a canon between the

voice and a bassoon alternating

with solo violin, is again

restricted to a single

instrumental line. The music

associated with the departure of

Abraham and Isaac with the two

serving boys for the place of

worship is a flute cadenza

punctuated by five string

chords. The next and longest

interlude, representing

Abraham’s journey alone with

Isaac for the sacrificial

infanticide, consists of a

succession of chords of

two-pitches in the

bass-register, and melodic

fragments played by alto flute.

At the start of the next

section, the point in the

narrative where Abraham collects

the wood for the burnt offering,

the vocal part is unaccompanied.

It begins on C sharp, the

referential pitch of the whole

work. Octave-doubled in bassoon

and bass clarinet and thrice

repeated, the pitch becomes

increasingly focal. To introduce

Abraham’s statement, “God will

provide the lamb”, which is

scored for trumpet and tuba, the

narration briefly employs Sprechstimme

(half sung, half spoken), Father

and son go together (two

bassoons) to the place where God

has bidden Abraham to build an

altar. The next episode, the

binding of Isaac to the altar,

and of Abraham brandishing his

knife, begins in the English

horn on C sharp and ends with

the same note in the bassoon.

The subsequent episode, the

angel crying out of Heaven, is

accompanied by the novel

combination of flute and tuba.

Harsh, forte chords in the full

strings punctuate God’s command,

“Do not lay thy hand upon the

boy”, as well as at the dramatic

moment when God says that

Abraham has not “withheld thy

son, thy only one, from me”.

The capturing of the ram in a

thicket inspired programme

music. The friskiness of the

animal is evoked by leaps and

rapid notes in the bassoon, and

by the least regular rhythms

Stravinsky ever wrote (12 notes

to be played in the time of 5,

11 notes in the time of 3, 5

notes in the time of 3, and 3

notes in the time of 5). The

next episode, the naming of the

place of Isaac’s non-sacrifice

as the Mount of the Lord, is

introduced by a slightly

different form of the interlude

before the ram-chasing. The

music is a three-part canon for

the voice, French horn, and tuba

ending in the most passionate

moment in the piece, a C sharp

sustained in four octaves in the

winds, followed by eight

repeated C sharps in the vocal

part to the words “And they

called the angel of the Lord to

Abraham”, accompanied by tuba

and horn in alternation and then

together. Rapidly repeated notes

of the clarinet on one pitch

should be understood as

Stravinsky’s musical image for

the multiplication of the seed

of Abraham. The short chords,

played by all of the wind

instruments together, with the

words “Blessed is thy seed in

all the nations of the earth”,

are a further instance of the

composer’s musical symbolism.

The ending, “And dwelt Abraham

in Beersheba”, the most moving

section of the cantata, is

introduced and accompanied by

three solo strings, replaced in

the final phrase by two

clarinets. The first and the

last note of this final verse is

C sharp.

The story of Abraham and Isaac

has inspired great visual art

(Ghiberti’s panel), great music

(Stravinsky’s), and great

philosophical literature

(Kierkegaard). Erich Auerbach’s

comparison of it in Mimesis

with Homer’s account of the

recognition of Odysseus by his

nurse Erycleia should also be

mentioned. Stravinsky was in his

eighties when he composed this

deeply-felt, dramatically and

musically original work. Its

emotional power is conveyed at

first hearing, but to understand

and love its musical content

requires repeated listening.

Élégie

The Élégie for solo

viola is one of Stravinsky’s

most affecting short works. Its

dedication to the memory of

Alphonse Onnou, violinist and

founder of the Pro Arte String

Quartet, was at the request of

the Quartet’s violist, Germain

Prévost, a close and longtime

friend of the composer. Unique

in Stravinsky’s music, he marked

the fingerings in the manuscript

and published score with the

comment that they were chosen to

underline the counterpoint.

The prelude begins with a song

and accompaniment figure. The

principal part suggests a

two-voice fugue, and at its

climax, the subject, the Dux, is

answered by its inversion, the

Comes, at the distance of two

silent beats in the second

voice. Prévost played the piece

for Béla Bartók in his New York

home before the public première.

Tchaikovsky / Stravinsky:

Bluebird Pas de Deux

In January 1941 Lucia Chase, the

founding Director of Ballet

Theater, commissioned Stravinsky

to arrange the four very brief

pieces comprising the Bluebird

ballet, excerpts from

Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping

Beauty re-scored for a

chamber orchestra. This was

Stravinsky’s first commission as

a refugee in the U.S. and he

greatly enjoyed his work, which

he achieved in a few days. All

that can be said about the

arrangement is that it provides

a study in Stravinsky’s

improvement over Tchaikovsky’s

orchestration. Stravinsky began

not by reducing the orchestra,

but by adding an instrument—a

piano—which provided at least

two new ideas as well as a

welcome element of articulation

and sonority.

For only two examples,

Stravinsky scrapped the original

flute duet that begins the Second

Variation and replaced it

with a duet for flute and

clarinet, thus creating a

dialogue and enlivening the

musical style. In the fourth

piece, Tchaikovsky attaches

appoggiaturas to each note of

the woodwind parts while

Stravinsky restricts the figure

to flute and piano alone, which

removes the thickness and

clumsiness in exchange for

elegance and clarity.

Robert

Craft

|

|

|

|

|