|

|

2 CDs

- 8.660272-73 - (c) 2009

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 11

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

The Rake's

Progress (1951) - Libretto by

Wystan Hugh auden (1907-1973) and

Chester Kallman (1921-1975

|

|

|

2h 08' 09" |

|

|

|

Prelude |

|

0' 32" |

|

1-1 |

|

Act I |

Scene 1

|

|

|

17' 55" |

|

|

|

-

Duet and Trio: "The woods are

green..." - (Anne, Tom, Trulove)

|

|

3' 17" |

|

1-2 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Anne, my dear..." - (Trulove,

Anne, Tom)

|

|

0' 54" |

|

1-3 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Here I

stand..." - (Tom)

|

|

0' 50" |

|

1-4 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Since it is not by merit..."

- (Tom)

|

|

1' 31" |

|

1-5

|

|

|

-

Recitative: "Tom Rakewell?" - (Nick,

Tom)

|

|

1' 25" |

|

1-6 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Fair lady..." - (Nick)

|

|

1' 57" |

|

1-7 |

|

|

-

Quartet: "I wished but once..." - (Tom,

Nick, Anne, Trulove)

|

|

3' 08" |

|

1-8 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "I'll call the coachman,

sir" - (Nick, Trulove)

|

|

0' 11" |

|

1-9 |

|

|

-

Duettino: "Farewell, farewell..." (Anne,

Tom)

|

|

1' 13" |

|

1-10 |

|

|

-

Recitativo: "All is ready, sir" - (Nick,

Tom)

|

|

0' 46" |

|

1.11 |

|

|

-

Arioso: "Dear Father Trulove" - (Tom)

|

|

1' 21" |

|

1-12 |

|

|

-

Terzettino: "Laughter and light..."

- (Tom, Anne, Trulove, Nick)

|

|

1' 22" |

|

1-13 |

|

|

Scene 2 |

|

|

12' 49" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: "With air commanding..." - (Roaring

boys, Whores)

|

|

2' 27" |

|

1-14 |

|

|

-

Recitative and Scene: "Come, Tom..."

- (Nick, Mother Goose, Tom)

|

|

3' 31" |

|

1-15 |

|

|

-

Chorus: "Soon dawn will glitter..."

- (Roaring boys, Whores, Nick)

|

|

0' 36" |

|

1-16 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Brothers of Mars..." -

(Nick)

|

|

0' 56" |

|

1-17 |

|

|

-

Cavatina: "Love, too frequetly

betrayed..." - (Tom)

|

|

2' 21" |

|

1-18 |

|

|

-

Chorus: "How sad a song" - (Whores,

Mother Goose)

|

|

0' 49" |

|

1-19 |

|

|

-

Chorus: "The sun is bright" - (Chorus,

Nick)

|

|

2' 09" |

|

1-20 |

|

|

Scene 3 |

|

|

7' 22" |

|

|

|

-

Introduction (Orchestra)

|

|

0' 48" |

|

1-21 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "No word from Tom" - (Anne)

|

|

0' 52" |

|

1-22 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Quietly, night..." - (Anne)

|

|

2' 03" |

|

1-23 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "My father!" - (Anne)

|

|

0' 54" |

|

1-24 |

|

|

-

Cabaletta: "I go, I go to him" - (Anne)

|

|

2' 45" |

|

1-25 |

|

Act II |

Scene 1 |

|

|

12' 56" |

|

|

|

-

Introduction (Orchestra)

|

|

0' 36" |

|

1-26 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Vary the song" - (Tom)

|

|

2' 00" |

|

1-27 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "O Nature, green

unnatyral mother..." - (Tom)

|

|

2' 08" |

|

1-28 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Always the quarry..." (Tom)

|

|

1' 23" |

|

1-29 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Master, are tou alone?"

- (Nick, Tom)

|

|

2' 31" |

|

1-30 |

|

|

-

Aria: "In youth the panting

slave..." - (Nick)

|

|

2' 08" |

|

1-31 |

|

|

-

Duet-Finale: "My tale shall be

told..." - (Tom, Nick)

|

|

2' 10" |

|

1-32 |

|

|

Scene 2 |

|

|

12' 36" |

|

|

|

-

Introduction (Orchestra)

|

|

1' 31" |

|

1-33 |

|

|

-

Recitative and Arioso: "How

strange!" - (Anne)

|

|

3' 06" |

|

1-34 |

|

|

-

Duet: "Anne! Here!" - (Tom,

Anne)

|

|

2' 15" |

|

1-35 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "My love, am I to remain

in here forever?" - (Baba, Anne,

Tom)

|

|

0' 56" |

|

1-36 |

|

|

-

Trio: "Could it then..." - (Anne,

Tom, Baba)

|

|

2' 45" |

|

1-37 |

|

|

-

Finale: "I have not run away..." - (Baba,

Tom, Town People)

|

|

2' 03" |

|

1-38 |

|

|

Scene 3 |

|

|

10' 26" |

|

|

|

-

Aria: "As I was saying..." - (Baba,

Tom)

|

|

1' 40" |

|

1-39 |

|

|

-

Baba's Song - (Baba)

|

|

0' 21" |

|

1-40 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Scorned! abused! Neglected!"

- (Baba)

|

|

1' 34" |

|

1-41 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "My heart is cold..." -

(Tom) |

|

0' 16" |

|

1-42 |

|

|

-

Pantomime - (Nick)

|

|

0' 58" |

|

1-43 |

|

|

-

Recitative-Arioso-Recitative:

"Awake?" - (Nick, Tom) |

|

1' 44" |

|

1-44 |

|

|

-

Duet: "Thanks to this excellent

device..." - (Tom, Nick)

|

|

1' 41" |

|

1-45 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Forgive me, master..."

- (Nick, Tom)

|

|

2' 12" |

|

1-46 |

|

Act III |

Scene 1 |

|

|

15' 52" |

|

|

|

-

Ruin, Disaster, Shame - (Town

People, Anne, Sellem)

|

|

3' 08" |

|

2-1 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Ladies, both fair and

gracious..." - (Sellem)

|

|

1' 25" |

|

2-2 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Who hears me, knows me..." -

(Sellem, Chorus, Baba)

|

|

3' 31" |

|

2-3 |

|

|

-

Aria: "Sold! Annoyed!" - (Baba,

Chorus, Tom, Nick)

|

|

0' 55" |

|

2-4 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Now, what was that?" -

(Chorus, Baba, Anne, Sellem)

|

|

1' 00" |

|

2-5 |

|

|

-

Duet: "You love him, seek to set him

right..." - (Baba, Anne, Sellem,

Chorus)

|

|

3' 29" |

|

2-6 |

|

|

-

Ballad Tune: "If boys had wings and

girls had stings..." - (Tom,

Nick, Anne, Baba, Sellem, Chorus)

|

|

0' 25" |

|

2-7 |

|

|

-

Stretto-finale: "I go to him..." - (Anne,

Baba, Sellem, Chorus)

|

|

0' 51" |

|

2-8 |

|

|

-

Ballad Tune: "Who cares a fig..." -

(Tom, Nick, Baba, Chorus)

|

|

0' 58" |

|

2-9 |

|

|

Scene 2 |

|

|

17' 28" |

|

|

|

-

Prelude (Solo String Quartet)

|

|

1' 36" |

|

2-10 |

|

|

-

Duet: "How dark, how dark and

dreadful is this place" - (Tom,

Nick)

|

|

4' 03" |

|

2-11 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Very well then..." - (Nick,

Tom)

|

|

1' 21" |

|

2-12 |

|

|

-

Duet: "Well, then. My heart is wild

with fear..." - (Nick, Tom,

Anne)

|

|

10' 28" |

|

2-13 |

|

|

Scene 3 |

|

|

20' 23" |

|

|

|

-

Introduction (Orchestra) |

|

0' 37" |

|

2-14 |

|

|

-

Arioso: "Prepare yourselves..." - (Tom)

|

|

1' 00" |

|

2-15 |

|

|

-

Dialogue: "Madmen's words are all

untrue..." - (Madmen, Tom)

|

|

0' 24" |

|

2-16 |

|

|

-

Chorus-minuet: "Leave all love and

hopo behind!" - (Madmen)

|

|

1' 12" |

|

2-17 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "There he is..." - (Keeper,

Tom, Anne)

|

|

0' 50" |

|

2-18 |

|

|

-

Arioso: "I have waited" - (Tom)

|

|

0' 58" |

|

2-19 |

|

|

-

Duet: "In a foolish dream..." - (Tom,

Anne)

|

|

2' 43" |

|

2-20 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "I am exceeding weary" -

(Tom)

|

|

0' 59" |

|

2-21 |

|

|

-

Lullaby: "Gently, little boat" - (Anne,

Chorus)

|

|

2' 32" |

|

2-22 |

|

|

-

Recitative: "Anne, my dear..." - (Trulove,

Anne)

|

|

0' 41" |

|

2-23 |

|

|

-

Duettino: "Every wearied body

must..." - (Anne, Trulove)

|

|

1' 35" |

|

2-24 |

|

|

-

Finale: "Where art thou, Venus?" - (Tom,

Chorus)

|

|

3' 15" |

|

2-25 |

|

|

-

Mourning-chorus: "Mourn for Adonis"

- (Chorus)

|

|

1' 06" |

|

2-26 |

|

|

-

Epilogue: "Good people, just a

moment..." - (Anne, Baba, Tom,

Nick, Trulove)

|

|

2' 31" |

|

2-27 |

|

|

|

|

Kayne

West, Soprano (Anne Trulove)

Jon Garrison, Tenor (Tom

Rakewell)

Arthur Woodley, Baritone (Father

Trulove)

John Cheek, Bass-baritone (Nick

Shadow)

Shirley Love, Mezzo-soprano

(Mother Goose)

Wendy White, Mezzo-soprano (Baba

the Turk)

Melvin Lowery, Tenor (Sellem)

Jeffrey Johnson, Bass (Keeper)

GREGG SMITH SINGERS

ORCHESTRA OF ST. LUKE'S

Robert CRAFT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

SUNY,

Purchase, New York (USA) - 18 to

18 May 1993

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory

K. Squires

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Gregory K.

Squires |

|

|

Editors

|

|

Richard

Price, Arlo McKinnon Jr.

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.660272-73 | 2 CDs | LC 05537

| durata 2h 08' 09" | (c)

2009 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

MusicMasters,

Vol. VI | 01612-67131-2 | 2

CDs | (p) 1994 | DDD

|

|

|

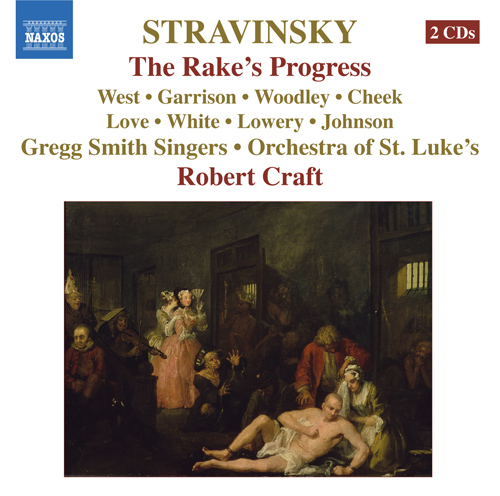

Cover |

|

A Rake's

Progress VIII: The Rake in

Bedlam by William Hogarth

(1697-1764)

(Courtesy of the Trustees of sir

John Soane's Museum, London /

The Bridgeman Art Library)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

2 CDs - 01612-67131-2

Volume VI - (c)

1994

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

|

Robert

Craft first met Stravinsky on

the same day that Auden

delivered the completed libretto

to the composer, and was

directly involved in what he

describes as “the first step” in

the composition of The

Rake’s Progress. This was

principally with regard to

helping Stravinsky master the

pronunciation, vocabulary and

rhythms of the English text, and

sharing the composer’s

excitement as the brilliantly

conceived score took shape. This

1993 recording, conducted by

Craft, is no less significant

than Stravinsky’s 1953

Metropolitan Opera recording,

available on Naxos Historical

8.111266-67.

The Rake's Progress: A Memoir

I met Stravinsky for the first

time on the same day that W.H.

Auden delivered the completed

libretto of The Rake’s

Progress to him in

Washington, D.C., 31 March 1948.

Returning to Hollywood from New

York five weeks later,

Stravinsky began to compose the

opera on 8 May adding the title

“Festival of May,” from the

second line of the libretto, at

the head of his first sketch.

When I visited him there at the

end of July, he had completed

the draft score through Shadow’s

line, “You are a rich man”, and

in the quartet that follows, he

was sketching Tom Rakewell’s

part, adding a sprinkling of

bass notes and an incipit

of the string accompaniment.

On my first day he played,

“sang”, and groaned the score

for me, stripped to his

sleeveless undershirt and the

talismanic medals that always

hung around his neck. The

visceral intensity of the

performance, reflecting the

throes of creation, seemed too

private to watch, and for a

moment I wanted to escape from

the intimacy of the small,

soundproof room. His rendering

of the soprano part sounded two

octaves, the tenor, one octave,

below the written pitch, and in

his struggles to find the

orchestra’s notes on the piano

from his draft-score, all sense

of tempi and rhythms

disappeared. He mispronounced

every word—even “Tom” came out

as “Tome”—and since he had not

overcome his born-to

pronunciation of “w”s as “v”s,

or shed his thick Russian

accent, the text was

unrecognizable. At the end,

bathed in perspiration, his face

beamed with pleasure.

I was to hear no more of the

opera until February 1949, when

he played the completed first

act for Balanchine, Auden,

Nicholas Nabokov, and myself in

a New York apartment. (The first

scene was finished on 3 October

the second begun two days later;

scene three is dated 16 January

1949.) From the beginning of

June 1949 I lived in

Stravinsky’s house, or nearby,

and during the composition of

the second and third acts was

separated from him only for

brief intervals. By the time of

my arrival he had written the

tenor arias at the beginning of

Act II, but he was not

optimistic about the next pieces

to be composed. He had

reservations about the

characterization of Baba the

Turk, not to mention Shadow’s

arguments for Rakewell to marry

her, which he thought specious,

abstract, and more likely to

baffle than to convince an opera

audience.

Stravinsky was beset by other

worries in that summer of 1949.

In his estimate the opera would

be more than twice the length of

any piece he had composed. The

Stravinsky catalogue of a

hundred or so works includes

only five or six of more than a

half-hour in duration, and the

time-scale of the majority is

far more brief than that. As

soon as he had sent off the

first scenes to his publisher,

apparently with no concern that

he might wish to revise any part

of them in the light of later

ones, he was obsessed by the

idea that he might not live to

complete the opera. Although

conducting was his principal

source of income, he reduced his

concert engagements to a minimum

in order to devote all of his

time to the opera, and at one

point he actually thought of

shelving it and accepting a

lucrative commission for a short

piece. In July 1949, while

composing the duet at the end of

scene 1, Act II, he complained

of sharp stomach pains - X-rays

would reveal a duodenal ulcer -

and a crippling one in his left

shoulder, diagnosed as a pinched

nerve. He was forced to follow a

strict diet thereafter and to

undergo daily neurological

treatments, but these ailments

were not entirely cured until he

had scored the last chord of the

Epilogue some twenty

months later.

During the gestation of the last

two acts of the opera I enjoyed

the privilege of being able to

observe the external signs of

Stravinsky’s creative processes

at close range. I was directly

involved in the first step. He

would ask me to read aloud, over

and over and at varying speeds,

the lines of whichever aria,

recitative, or ensemble he was

about to set to music. He would

then memorize them, a line or a

couplet at a time, and walk

about the house repeating them,

or when seated in his wife’s car

(a second-hand, ancient and

dilapidated Dodge) en route to a

restaurant, movie, or doctor’s

appointment. Much of the

vocabulary was unfamiliar to him

but he soon learned it and began

to use it in his own

conversation, charging someone

with “dilatoriness”, or excusing

himself for having to “impose”

upon us, which sounded very odd

from him. It can be said that

his transformation from a

primarily French-speaking to an

American-speaking artist took

place in correspondence with the

composition of the opera. (The

deficiencies of my own

linguistic education were also a

factor, of course.) I should add

that after The Rake’s

Progress and until the end

of his life, Stravinsky, a

voracious and constant reader,

confined himself almost

exclusively to books in English,

the major exception being his

addiction to the romans-policiers

of Georges Simenon.

In setting words Stravinsky

began by writing rhythms in

musical notation above them,

note-stems with beams indicating

time values—quarters

(crotchets), eighths (quavers),

sixteenths (semiquavers),

thirty-seconds

(demisemiquavers), triplets, and

so forth. In the act of doing

this, melodic or intervallic

ideas would occur to him, and be

included either in the same line

or just above. In Shadow’s

“giddy multitude” aria, for

example, the pitches and harmony

given to the words, “ought of

their duties”, came to the

composer’s imagination during

his preliminary sketch of

rhythms, and it remained

unchanged to the final score. In

the opera, tonalities do not

change from first notation to

full score; melodic lines,

rhythms, note-values, metres,

instrumentation all undergo

improvements and refinements,

but not tonality and harmony.

A fair number of “X”-ings-out,

followed by rewrites, are a

feature of the opera sketches.

If an ongoing melodic, harmonic,

or rhythmic development

suggested itself after he had

completed a draft, he would add

it in a blank space in his

manuscript, squeezing it into a

corner or cranny of even the

most crowded page, circling it

like a speech-balloon in a

comic-strip, and drawing a line,

sometimes long and winding but

with arrows and road signs, to

the place of insertion in the

main sketch. Staves were traced

with his assorted sizes of

styluses—he did not use printed

music paper—on large sheets of

manila that he thumb-tacked or

clipped to a cork board attached

to the music rack of his piano.

The full orchestra score was

written with a soft lead pencil

on sensitized transparent music

paper, sprayed to prevent

smudging, and reproduced by the

ammonia vapour Ozalid process.

Stravinsky wrote the full score

at a slanted desk, with the

final draft score on a stand

just above, and wrote, after

plotting the numbers of measures

and score systems to fit the

page, directly from the draft.

In passages of comparatively

complex orchestration, he would

take time to write a trial

measure or two in full score in

pencil and on loose sheets of

yellow carbon paper. If his

layout of a score page proved to

be less than perfect, which

happened only very infrequently,

he would rewrite it in its

entirety rather than erase. His

well-known remark that music

should be composed avec la

gomme is a criticism of

the works of certain others, not

of his own.

Stravinsky’s composing day, and

composition was exclusively

daytime work for him, began with

playing the music he had written

the day before, or most

recently. I often joined him in

this, taking the treble parts;

he always insisted on playing

the bass himself. The task of

orchestrating, not unduly

onerous in his case, since he

had worked out the

voice-leadings in the drafts,

was reserved for the evenings.

Quite regularly, at his request,

I read to him during these soirées.

He would interrupt me from time

to time in order to concentrate

on an intricacy of some kind, or

try out a chord on the piano,

then say, “And?” The first book

that we finished was Mme

Calderon de la Barca’s 1830s

classic, Life in Mexico,

in the Everyman edition. He

remembered the contents, I

should add, at least as long and

as clearly as I did, which seems

to prove that he had a

compartmented mind.

Stravinsky entered indications

for instrumentation in even the

earliest sketches, and rarely

revised them thereafter. Only

two instances of the latter come

to mind. First, the initial

draft of the reprise of the

choral march in the Brothel

scene specifies the second horn

as the obbligato

instrument; then, while writing

the final draft, he realized

that the part would stand out

more distinctly in the trumpet.

Second, Shadow’s appearances are

associated with cembalo

flourishes. After the first of

these, in response to Tom

Rakewell’s “I wish I had money”,

he pronounces the protagonist’s

name, whereupon a shorter,

related flourish follows, also

played by cembalo and provided

in the original sketch with

keyboard fingerings. The final

score transfers this to bassoon,

partly to preserve the timbral

integrity of the entire motive,

partly because the wind

instrument “echo” adds an

element of parody.

Stravinsky reshaped melodies as

he worked. A small but stunning

improvement in this sense is the

rewriting, a third higher in the

last version than in the first,

of the last three notes for the

line, “the heart for love dare

everything”. Then, too, in its

first form the trumpet solo in

the Prelude to Act II,

scene 2, develops differently

from the way we know it. And

Baba’s breakfast patter—which in

the first sketch is half purely

rhythmic, half melodic—is

frequently interrupted by rests.

At some point after he had

already blocked out the

syllables within the metres,

Stravinsky realized that the

dramatic intent is an effect of

breathlessness, which he then

achieved partly by converting

the sixteenth notes

(semiquavers) that are followed

by rests to eighth notes

(quavers). I should also mention

that this first Baba aria was

composed after the second, the

trumpet solo after the aria it

introduces; Stravinsky did not

always compose in the order of

the libretto.

Yet what strikes us most about

Stravinsky’s creative procedures

is not the discrepancies between

first and final versions but the

overwhelming degree of

resemblance, despite the

enormous growth of his powers as

an opera composer from the early

to the ultimate scenes. Consider

only one aspect of this: the

ever-greater naturalness of the

word setting. In Act III words

and music fuse and complement

each other, accent and metre,

vocable and vocal register, are

in agreement. Here Stravinsky

feels the right speed and pitch

range for the tricky word

“dilatoriness”, and the

orchestration that enhances

verbal articulation, as in the

accompaniment, pizzicato with

crisp double-tongued trumpet

notes, that make the consonants

sparkle in the Bedlamite chorus:

Banker,

beggar, whore and wit

In a

common darkness sit

To some

extent the greater flow and

continuity in the third act than

in the first two can he

attributed to the absence of

background-filling recitatives,

and to thematic and stylistic

linkages from scene to scene—the

variations on the Ballad-Tune

(itself borrowed from Mozart’s A

major keyboard sonata) in all

three scenes, and the

embellishments that stylize

Rakewell’s fear in the graveyard

and the still more florid ones

in his dying scene. But above

all Act III has genuine

music-dramatic power, not only

in Shadow’s “I burn, I freeze”,

but in the quiet, hollow unison,

the only one in the opera, of

the chorus’s “Madman, no one has

been here”. Stravinsky was

inspired by the two final scenes

months before he had read the

libretto. Without words to set,

but impatient to compose, he

wrote the beautiful

string-quartet Prelude to

the Graveyard scene on 11

December 1947, three weeks after

the scenario had been drafted,

and three years before he

composed the scene itself, in

November 1950.

Robert

Craft, © 1994

|

|

|

|

|