|

|

1 CD -

8.557507 - (c) 2009

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

Octet

for Wind Instruments (1922-23)

|

*

|

|

13' 27" |

|

|

-

Sinfonia · Allegro

|

|

3' 39"

|

|

1

|

|

-

Theme and Variations

|

|

6' 34" |

|

2 |

|

-

Finale

|

|

3' 14" |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerto

in E flat (Dumbarton Oaks) (1938)

|

** |

|

13' 03" |

|

|

-

Tempo giusto |

|

4' 18" |

|

4 |

|

-

Allegretto

|

|

3' 48" |

|

5 |

|

-

Con moto

|

|

4' 57" |

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

in C (1940) |

*** |

|

27' 40" |

|

|

-

Moderato alla breve

|

|

9' 24" |

|

7 |

|

-

Larghetto concertante

|

|

6' 27" |

|

8 |

|

- Allegretto

|

|

4' 47" |

|

9 |

|

-

Largo; Tempo giusto, alla breve

|

|

7' 02" |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

in Three Movements (1942-45) |

° |

|

21' 29" |

|

|

-

♩ = 90

|

|

9' 49" |

|

11 |

|

- Andante ·

Interlude

|

|

5' 40" |

|

12 |

|

-

Con moto

|

|

6' 00" |

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

Octet for Wind Instruments

TWENTIETH

CENTURY CLASSICS

ENSEMBLE

- Elizabeth Mann, flute

- William Blount, clarinet

- Marc Goldberg, bassoon

- Thomas Sefkovic, bassoon

- Chris Gekker, trumpet

- Carl Albach, trumpet

- Michael Powell, trombone

- John Rojak, bass

trombone

|

Concerto

(Dumbarton Oaks)

ORCHESTRA

OF ST. LUKE'S

Robert

CRAFT, Conductor |

Symphony in C

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA

Robert

CRAFT, Conductor |

Symphony in Three

Movements

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHETRA

Robert

CRAFT, Conductor |

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

Abbey Road

Studio One, London (England):

- 16 and 17 November 1999

(Symphony in C)

- 14 and 15 November 1999

(Symphony in Three Movements)

SUNY, Purchase, New York (USA):

- 1992 (Octet)

- 1991 (Concerto Dumbarton Oaks)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory

K. Squires

|

|

|

Engineers |

|

Michael

Sheady (Symphony in C, Symphony in

Three Movements)

|

|

|

Assistant

engineer

|

|

David

Flower (Symphony in C, Symphony

in Three Movments)

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557507 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 75' 39" | (c)

2009 | DDD

|

|

|

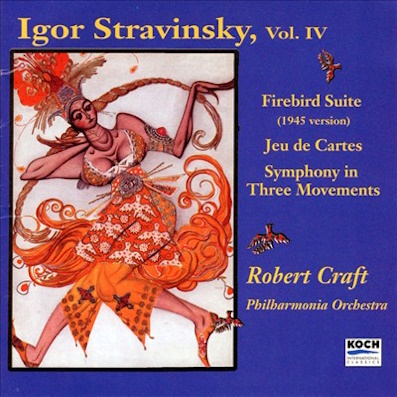

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Koch

International, Vol. V |

3-7504-2 | 1 CD | (p)

2001 | DDD (Symphony in

C)

Koch

International,

Vol. IV |

3-7472-2 | 1

CD | (p) 200 |

DDD (Symphony

in Three

Movements)

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

MusicMasters,

Vol. III | 01612-67103-2

| 1 CD | (p) 1992 | DDD

(Octet)

MusicMasters,

Vol. IV |

01612-67113-2

| 1 CD | (p)

1993 | DDD

(Concerto

Dumbarton

Oaks)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Spatial Force

Construction by Lyubov'

Sergeevna Popova (1889-1924)

(Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow,

Russia / The Bridgeman Art

Library) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

1 CD - 01612-67103-2 - Volume

III

(c) 1992 *

1 CD - 01612-67113-2 -

Volume IV

(c) 1993 **

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

1 CD -

3-7504-2 - Volume V

1 CD -

3-7504-2 - Volume V

(c) 2001 ***

1 CD -

3-7472-2 - Volume IV

1 CD -

3-7472-2 - Volume IV

(c) 2000 °

|

With

neo-classical works such as

those on this disc, Stravinsky

showed that great music could

still be composed with the

simplest of means, recalling

Beethoven’s achievement yet

using his own thoroughly modern

rhythmic vitality, grace and

refinement. The Robert Craft

Collection has been acclaimed as

“one of the more adventurous and

interesting recording projects

by Naxos”, with individual

titles receiving the highest

praise: “an almost unsurpassable

choice” (8.557501), “as with all

the releases in this magnificent

series, the performances are

excellent” (8.557502), “a disc

of major importance” (8.557508).

Octet (1922–23)

Stravinsky made his official

début as a conductor introducing

the Octet in a

Koussevitzky concert at the

Paris Opéra on 18 October 1923.

The performance followed another

major première, Prokofiev’s First

Violin Concerto (his

magnum opus, in this reviewer’s

opinion), and preceded the Eroica

Symphony, a scarcely believable

neighbourhood for Stravinsky’s

brief (13-minute) opus for eight

solo winds, a large part of

which features only two

instrumental parts together at a

time. No wonder the Octet

ensemble had to be screened off

and moved to the stage-front of

the cavernous Opéra.

The Octet was secretly

dedicated to Stravinsky’s

mistress, Vera de Bosset. It

also happens to be the happiest

of his early pieces. It has

never been fully put into

perspective, though it is the

composer’s first completely

neo-classic opus. The first

movement, Sinfonia – Allegro,

has a key signature (E flat). It

begins with a Lento

introduction. A single trumpet

note opens the piece and is

answered by the woodwinds—flute,

clarinet, two bassoons—which

play an extended, quiet quartet,

featuring the flute in some of

the tenderest music in the

piece. The introduction

concludes with a recapitulation

of the beginning.

The following Allegro,

the body of the piece but barely

longer than the introduction, is

rollicking music, thematically

simple, always syncopated,

lightly scored—duets,

trios—constantly varying

instrumental colours. Most of

the music is diatonic, as is the

complete work, with one

exception. A new characteristic

is the prominence of scales:

they occur in all three

movements. The form and harmonic

language are eighteenth-century

classical.

The second movement, a Theme

and Variations, is a

showcase featuring instrumental

virtuosity. The first variation

is repeated after the second,

after the third, and before the

fourth, the fugal slow movement,

and the Octet’s only

harmonically dense one. The last

movement is a romp, with a

pleasing, off-the-beat, jazz

coda.

The Octet, a turnaround

in every way from The Rite

of Spring, performed a

decade earlier, was surprisingly

well received.

Concerto in E flat (Dumbarton

Oaks) (1938)

Stravinsky conducted Bach’s Third

Brandenburg Concerto in

Cleveland in February 1937, and

was not able thereafter to

forget the piece. He spent the

following summer in Chateau de

Montoux near Geneva, composing a

concerto inspired by the Bach,

the beginning of which is an

unmistakable adaptation from

Bach’s first theme. This has

remained the principal criticism

of the work ever since, though

the choice should be considered

among the excellences of the

piece. Its musical invention and

craftsmanship are on the highest

level.

Dumbarton Oaks is the

Washington, DC estate of Robert

and Mildred Bliss. They

bequeathed it to Harvard

University, under whose

administration it became the

University’s Center for

Byzantine Studies. The property

is best known today for its

magnificent Italian gardens.

Stravinsky had known the Blisses

before the Concerto

commission and they were friends

until his death. He saw them in

Athens in 1956 and in July of

that year he was a guest on

their yacht on an excursion from

Istanbul to the Black Sea. In

the cultural world Mildred Bliss

was sans pareil. (Auden

once told me that he dreaded

being seated next to her at

dinner parties because “she

converses with me only in Greek

or in English words I do not

know.”)

The Concerto, written

two decades after the Octet,

and his last work completed in

Europe, is a perfect partner for

it. It is traditional in form -

fast, slow, fast - and in

tonality, E flat, B flat, E

flat. Jerome Robbins made a

delightful ballet of it in 1972.

The original manuscript is in

the Dumbarton Oaks library,

along with that of Stravinsky’s

Septet (1954), also

commissioned by the Blisses, and

first performed there conducted

by Stravinsky. The première of

the Concerto was in the

Bliss domicile, conducted by

Nadia Boulanger, on 8 May 1938.

Symphony in C (1940)

The first movement, in

traditional sonata form, is

Stravinsky’s longest in a single

meter since 1906. But the

rhythmic tensions of the piece

are one of its wonders. The

accented off-beats continue to

surprise us no matter how well

we know the music. Rests are

also surprisingly extended. The

rhythmic vocabulary - eighths

and quarters mainly, a few half

notes, sixteenths as connecting

lines and part of an

accompaniment figure - are

almost as restricted as in the

first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth

Symphony. Having mentioned

that capolavoro, I

should add that the increased

use of the dotted figure in the

latter part of the movement, and

of the dotted-quarter rest,

building to the climax, is

remarkably Beethovenian. The

thematic material is restricted

as well, and is as devoid of

chromatics as any music of its

time. The modulations, with one

exception, do not wander to

remote keys, but favour the

subdominant and dominant, and

the excursions through F minor,

E, D, E flat minor are brief.

The movement’s most striking

episode is the ending. Flute and

clarinet, two octaves apart,

play the first theme legato,

over a staccato ostinato

figure in violas and second

violins that continues unchanged

until the final chords. The

melody does change, if only by a

single upper note involving an

octave leap that brings new

brightness. Stravinsky seems to

be saying that great music can

still be composed with the

simplest means.

Stravinsky’s elder daughter died

of tuberculosis at the end of

November 1938. His wife,

Catherine, died from the same

disease on 2 March 1939. He did

not complete the first movement

until 17 April 1939, by which

time he was stricken with

tuberculosis himself and

confined to the same sanatorium,

Sancellemoz, in the

Haute-Savoie, where his wife and

daughters had spent so much of

their lives. The second

movement, Larghetto, was

begun there on 27 April. It

employs a reduced orchestra,

omitting the tuba, trombones,

timpani, two of the horns, and

one of the trumpets. His

sketchbook shows that he wrote

most of the movement in

quartet-score form. The full

draft was finished on 19 July,

after very little

trial-and-error sketching. The

music is elegiac, with

long-line, elegantly embellished

melodies. The duets between the

oboe and violins are graceful

and refined beyond any of music

of the twentieth century known

to this writer, and even the agitato

middle section is soft and

subdued.

The manuscript score of the

second movement survived a

perilous wartime adventure.

Willy Strecker, the Symphony’s

publisher, visited the composer

twice in Sancellemoz, to bring

each of the first two movements

safely back to Schott, Mainz for

engraving. On the first visit

Stravinsky gave the manuscript

of the first movement to him,

and tried (unsuccessfully) to

establish a connection for

future transactions through

Luxembourg, Stravinsky being a

banned composer in the Third

Reich, and Strecker being

forbidden to send proofs (and

royalties) to him in France. On

the second visit, only ten days

before the beginning of World

War II, Stravinsky parted with

the score of the second movement

in the same way. (The last two

movements were printed in New

York during World War II.) When

Schott had engraved the second

movement, Strecker entrusted the

manuscript to the wife of Paul

Hindemith to return it to

Stravinsky in New York, where

she was hoping to rejoin her

husband. Somehow, she managed to

obtain passage through Italy in

1942 and reach the United

States, but the score was not

restored to Stravinsky until 1

January 1953. On this date

Hindemith directed a matinée

concert of his music in Town

Hall, to which Stravinsky,

“self-confined” to bed with a

cold (in order the escape the

concert), had sent me as deputy.

After it, Hindemith came to

visit Stravinsky in his hotel

(the Gladstone, on East 52nd

Street) and at the end of a

vivacious meeting withdrew the

manuscript from a valise

and presented it to its

composer. Though Stravinsky had

long since forgotten about the

manuscript, he was pleased to

see it again, and to my

amazement and overwhelming

thrill he inscribed it to me as

a New Year’s gift.

The third movement was composed

in Cambridge and completed in

Boston on 27 April. The fourth

is dated Hollywood, 17 August.

The composer conducted the

première with the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra on 7 November

1940.

Symphony in Three Movements

(1942–45)

Stravinsky began the Symphony

in 1942, not at the beginning

but with the music at two bars

before rehearsal [70] through

the second bar of [80].

Composing backwards, so to

speak, as he had done in other

works, he then wrote the music

from the upbeat to the bar

before [59] to a few bars before

[70]. The three connecting bars

between these two sections

repeat the rhythm of the three

repeated chords after rests in

the first movement of the Eroica

Symphony. This is followed in

the sketchbook by a draft of the

entire first section through the

canon for two bassoons of the

third movement. Returning to the

opening movement, the composer

continued to work toward the

beginning, adding the music from

[34] to [56], then the section

from [22] to [39]. Surprisingly,

the latter section was composed

as a separate piece on pages

from a loose-leaf notebook, and

later inserted as a continuation

of the opening of the Symphony.

A sketch for bars [143–172] is

marked “new, with piano”, making

one wonder what Stravinsky

thought he was composing when he

began the piece. His biographer

at the time, Alexander Tansman,

believed that it was a concerto

for orchestra with a solo concertante

role for piano. But the New York

Philharmonic Symphony had

commissioned a “Victory

Symphony”, and the end movements

are clearly martial in spirit.

Indeed, the third movement

follows a programmatic scenario

of the progress of World War II.

It begins with a parody march of

goose-stepping soldiers parading

in triumph in 1940. The faster,

syncopated, and more rhythmic

music that follows was inspired

by cinematic scenes of the

recrudescence of the Allies. The

march returns, less

aggressively, and finally comes

to a halt, symbolizing the

breakdown of the Nazi war

machine in the winter of 1943

and the stasis at Stalingrad.

Here it should be said that

Stravinsky followed the conflict

with maps on which he flagged

the day-to-day positions of the

armies on the Russian, Italian,

then Western fronts. Once again

a proud Russian, he participated

in money-raising concerts for

the war effort. He wrote the

final bars of the Symphony

during the surrender of Japan.

The post-Stalingrad music begins

with the solo trombone playing a

two-note motive twice, each time

different in length and a step

apart, as if the player were

“warming up” in a room by

himself. After a pause, the

piano plays the same notes, and

makes a fugue subject of them.

The harp, the featured

instrument of the second

movement, as is the piano of the

first, enters next and plays in

duet with the piano. The

bassoons and strings form a

third, fugal voice, after which

an agitated figure leads to the

development of the Latin

American rhythm heard earlier in

the movement but now jubilant.

The second movement was composed

in 1943 for the “Apparition of

the Virgin” scene in the film of

Franz Werfel’s Song of

Bernadette, but not used

there. Stravinsky and Werfel had

been close friends, and the

inclusion of the Bernadette

music should be thought of as a

memorial to the writer. It has

no connection with the

Broadway-style first and last

movements but fits perfectly

between them.

Robert

Craft

|

|

|

|

|