|

|

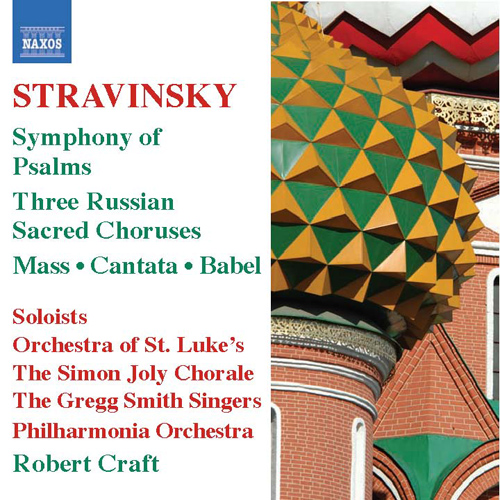

1 CD -

8.557504 - (c) 2006

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

Three

Russian Sacred Choruses |

* |

|

4' 45" |

|

|

-

Otche Nash (Pater Noster)

(1926)

|

|

1' 23" |

|

1 |

|

-

Ave Maria (1934)

|

|

1' 04" |

|

2 |

|

-

Credo (1932)

|

|

2' 17" |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mass

(1944-48)

|

** |

|

17' 09" |

|

|

- Kyrie

|

|

2' 37" |

|

4 |

|

-

Gloria

|

|

3' 56" |

|

5

|

|

-

Credo

|

|

4' 25" |

|

6 |

|

-

Sanctus |

|

3' 17" |

|

7 |

|

-

Agnus Dei

|

|

2' 55" |

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cantata

for 5 instruments, female chorus,

mezzo-soprano and tenor (1951-52)

|

*** |

|

23' 46" |

|

|

-

A Lyke-Wake Dirge (Versus I;

Prelude)

|

|

1' 32" |

|

9 |

|

-

Ricercar I: "The Maidens Came"

|

¤

|

4' 04" |

|

10 |

|

- A

Lyke-Wake Dirge (Versus II;

1st Interlude)

|

|

1' 35" |

|

11 |

|

-

Ricercar II: "Tomorrow Shall Be"

|

¥

|

10' 42" |

|

12 |

|

- A

Lyke-Wake Dirge

(Versus III; 2nd

Interlude)

|

|

1' 33" |

|

13 |

|

-

Westron Wind

|

¤ ¥ |

2' 07" |

|

14 |

|

- A Lyke-Wake Dirge (Versus IV;

Postlude)

|

|

2' 14" |

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Babel

(1944)

|

°

|

|

4' 57" |

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

of Psalms (1930, rev. 1948)

|

°° |

|

22' 25" |

|

|

-

Psalm 38, versee 13 and 14

|

|

3' 35" |

|

17 |

|

-

Psalm 39, verses 1 to 5

|

|

7' 12" |

|

18 |

|

-

Psalm 150 (entire)

|

|

11' 38" |

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

Pater Noster, Ave

Maria, Credo

THE

GREGG SMITH SINGERS

Robert CRAFT

|

Mass

THE

GREGG SMITH SINGERS

ORCHESTRA OF ST.

LUKE'S

Robert CRAFT

|

Cantata

Mary

Ann Hart, Mezzo-soprano

¤

Thomas Bodgan, Tenor ¥

Fred Sherry, Cello

Stephen Taylor, Oboe

Melanie Field, Cor Anglais

& Oboe

Michael Parloff, Flute

Bart Feller, Flute

THE GREGG SMITH SINGERS

Robert CRAFT

|

Babel

David Wilson-Johnson, Narrator

SIMON JOLY CHORALE

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT |

Symphony of

Psalms

SIMON

JOLY CHORALE

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT |

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

SUNY,

Purchase, New York (USA):

- 1992 (Three Russian Sacred

Choruses)

- 1995 (Mass)

- 9-15 1995 (Cantata)

Abbey Road Studio One, London

(England):

- 27 March 2002 (Babel)

- 5-6 January 2001 (Symphony of

Psalms)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory

K. Squires

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557504 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 73' 03" | (c)

2006 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Koch

International, Vol. VII

| 3-7777-2 | 1 CD | (p)

2002 | DDD (Babel)

Koch

International,

Vol. VI |

KIC-CD-7514 |

1 CD | (p)

2002 | DDD

(Symphony of

Psalms)

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

MusicMasters,

Vol. II | 01612-67086-2

| 1 CD | (p) 1992 | DDD

(Three Russian Sacred

Choruses)

MusicMasters,

Vol. VII |

01612-67152-2

| 1 CD | (p)

1995 | DDD

(Mass)

MusicMasters,

Vol. VIII |

01612-67158-2

| 1 CD | (p)

1995 | DDD

(Cantata)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

St Basil's

Cathedral by Vladimir

Pomortsev

(Dreamstime.com) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

1 CD -

01612-67086-2 - Volume

II

(c) 1992 *

1 CD -

01612-67152-2 -

Volume VII

(c) 1995 **

1 CD

-

01612-67158-2

- Volume VIII

(c) 1995 ***

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

1 CD -

3-7477-2 - Volume VII

1 CD -

3-7477-2 - Volume VII

(c) 2002 °

1 CD -

KIC-CD-7514 -

Volume VI

(c) 2002 °°

|

This

disc of sacred choral music

features the masterly Symphuny

of Psalms. which

Stravinsky dedicated "to the

glory of God". The composer

himself wrmr “It is not a

symphony in which I have

included Psalms to be sung... it

is the singing of Psalms that I

am symphonising." The Mass

(1944-48) dates from the

composer's first decade in

America. and is deeply rooted in

medieval chant. Cantata

(1951-52) consists of nine

canons, the centrepiece of which

is the Ricercare for

tenor, in which Christ foretells

his cCrucifixion. In Babel

(1944), Stravinsky uses text in

which the descendants of Noah

are frustated in their attempt

to build a tower reaching

heaven.

Three Russian Sacred

Choruses • Mass • Cantata •

Babel • Symphony of Psalms

The texts of the three Russian

Sacred Choruses, Pater

noster, Ave Maria

and Credo, are in

Slavonic. They are intended to

be used in the liturgy of the

Russian Orthodox Church, which

forbids the participation of

musical instruments. The first

piece is a chant, the second a

melody in the Phrygian mode, the

third a chant in falso

bordone;in 1964 Stravinsky

recomposed the music of the Credo,

parsing the rhythms into barred

units. For a 1929 Latin version

he first heard the music in

Paris in 1934 in a memorial

service for Samuel Dushkin's

patron, Blair Fairchild.

Stravinsky's Mass is the

most perfectly sustained in its

musical emotion of the creations

from his first decade in

America, even though he

interrupted work on it for four

years between the initial two

movements and the final three.

Part of the explanation for this

could be that unlike all of his

other music of the period it is

an ancient ritual, sung in

Latin, deeply rooted in medieval

chant and Byzantine design, and

free of any American influence.

In other respects, sonority,

harmony, and rhythm, completely

new.

The division of the instrumental

accompaniment into a quintet of

oboes and bassoons and a quintet

of trumpets and trombones is a

master-stroke. The sonorities

and volumes offer a wide range

of contrasts, including staccato

and legato. Like the chorus, the

wind instrumentalists must

breathe, hence the pre-eminence

of phrasing. In the Agnus

Dei, the orchestra and

chorus are separated, the

introduction and interludes are

purely instrumental, the choral

responses purely a cappella.

This device supports the

intonation of the choral

harmony, especially in the

dissonant minor-second

combinations, Stravinsky's

favourite interval.

The antiphonal concept is

developed within the chorus

itself in the Gloria and

the Sanctus by the

division of solo voices,

followed by full choral

responses. Stravinsky declared

somewhere that one of his goals

in the Mass setting was to

eliminate ornament. He signally

failed in this aim in these two

movements, but in the solo

parts, especially in the Gloria,

composed the work's most

beautiful music.

The centrepiece of the work, the

Credo, is the one

non-antiphonal, non-polyphonic

movement. Here the text

determined the musical scheme.

The piece is a chant, falso

bordone, and here alone

the rôle of the instruments is

traditionally accompanimental.

It provides pitches, rhythms,

brief passages of counterpoint,

and brief moments of

respiration. Nevertheless, and

despite the built-in monotony of

the rhythm, Stravinsky manages

to endow the music with form.

Toward the end the quiet

chanting becomes louder and

expands upward in range to a

climax which is prolonged by a forte

fermata. The next bar

returns briefly to the

beginning, a stunning effect

comparable to the return of the

first theme in a sonata

movement. The Amen which

concludes the piece is detached

from it by a slower tempo, a

return to a cappella

polyphony and to pianissimo.

Througout the Mass, the word

takes priority over the music.

Here one feels truly that "In

the beginning was the Word."

This architectural guide to a

musical masterpiece fails to

convey what perhaps should have

been proclaimed at the outset,

namely that it is powerfully

dramatic, and that the three

shouts of "Hosanna" in

the Sanctus are one of

Stravinsky's most thrilling

climaxes.

In January 1949, Stravinsky

received the five volumes of W.

H. Auden's and Norman Pearson's

Poets of the English Language.

He began to read in it from the

latter part of Volume One,

Langland to Spenser. His musical

ear brought him to a halt at the

Elizabethan bridal song "The

Maidens Came," which he

determined to set to music, and

did so on finishing The

Rake's Progress in

February–March 1951. He was not

aware that, of the many versions

of the poem, Auden had chosen

the one by the Chaucer scholar

E. Talbot Donaldson, whose text

Stravinsky followed:

The maidens

came

When

I was in my mothers bower;

I

hade all that I wolde.

The

baily beryth the bell away;

The

lilly, the rose, the rose I

lay.

The

silver is whit, red is the

golde,

The

robes they lay in fold.

The

baily beryth the bell away;

The

lilly, the rose, the rose I

lay;

And

through the glasse window

Shines

the sone.

How

should I love and I so

young?

The

baily beryth the bell away;

The

lilly, the rose, the rose I

lay.

For

to report it were now

tedius:

We

will therfor now sing no

more

Of

the games joyus.

Right

mighty and famus

Elizabeth,

our queen princis,

Prepotent

and eke victorius,

Virtuos

and bening,

Lett

us pray all

To

Christ Eternall,

Which

is the hevenly King,

After

ther liff grant them

A

place eternally to sing.

Amen.

The

speaker is presumably a young

bride awaiting her bridegroom,

but the identity of the bailey

and why he bears the bell away

is not known. The poem is an

excerpt from a much longer one,

printed in full only in 1901 in

Volume 107 of the Archiv für

neuere Sprechen und

Literaturen, by the

scholar Bernhard Fehr of

Southgate-on-Sea. The date of

the poem is assumed to be soon

after Elizabeth's victory over

the Armada (1588). More recent

scholarship associates the poem

with May Day festivities in and

around Durham Castle; the

"glasse window" probably refers

to the East Window of Durham

Cathedral. A musical setting

from the period reveals that the

first line is really the title,

and that the last line of the

first stanza should be a

repetition of the penultimate

line. An earlier, ribald version

of a fragment of the poem is

found in John Taverner's XX

Songes (1530). Here the refrain

"the baily beryth the bell away"

has been interpreted as "We

maidens beareth the bell," i.e.,

we take the prize. The bell

probably refers to the swelling

of pregnancy.

At the end of January 1952,

after a six-month hiatus from

creative work, Stravinsky began

to compose Ricercar II,

"Tomorrow Shall Be My Dancing

Day" (taken from Sandy's

Christmas Carols, London

1839). Webern's Orchestra

Variations, heard in

Baden-Baden in October 1951,

made a profound impression on

Stravinsky, but the Cantata

employs neither "serialism" nor

"atonality," and could not have

been written if these

developments had not occurred.

The first notation for the

cantus cancrizans of Ricercar

II is dated 8 February

1952, and the movement was

completed two weeks later on 22

February. The duet "Westron

Wind," beginning with the

rhythmic figure now appearing at

the end, was composed before the

Ricercar, in the week

beginning 2 February, but was

not fully scored until 22 March.

Work was interrupted by another

European concert tour in late

April–June, after which the Lyke-Wake

Dirge was written in

California in July. Stravinsky's

first plan was to compose a

prelude, interludes, and a

postlude for instruments, but,

impatient to begin work on the Septet,

he decided instead on the less

time-consuming repeated

choruses.

One of Stravinsky's most moving

creations, the Cantata

followed naturally from The

Rake's Progress, and was

in fact composed (the duet and

the tenor Ricercar) with

the voices of Jennie Tourel and

Hugues Cuénod in mind,

respectively Baba the Turk and

Sellem in the Venice production

of the opera. (Stravinsky may

even have thought of the line, "The

Devil bade me make stones my

bread," in Ricercar II,

as a link to the bread machine

in the opera.)

Most of "The maidens came …"

is accompanied by the woodwind

quartet, without the cello,

which is silent under the pairs

of winds at the words "how

should I love?" (note the

oboe high-"C") as it is again

near the end of the prayer that

concludes this lovely lyric. In

the dramatic recitative, "right

mighty and famus Elizabeth"

- which could only refer to the

triumph over the Spanish Armada

- the instruments provide

chordal punctuation. "The

maidens came …" was

originally scored for flutes and

cello alone, but to enrich the

polyphony and relieve the

timbres, Stravinsky added oboes

and an English horn. The seven

short sections of the song

switch back and forth between

the tonalities of C and B flat

and their related minors, until

the last phrase, when, at the

words "after life," the

tonal centre lifts stunningly to

the remote key of B.

The Cantata's

centrepiece and most innovative

movement is the tenor Ricercar,

in which Christ foretells His

Crucifixion on the morrow,

calling it "my dancing day."

The music contains only five

different pitches, and is

exposed in a one-bar

introduction in which the cello

doubles the first flute in a

high register, a sonority

suggesting Renaissance

instruments, while the second

flute doubles the melody an

octave lower. The tenor repeats

the subject with changes in

rhythm, then sings it in

retrograde order (more rhythmic

changes), inverted order, and

retrograde inverted order, in

which a sixth pitch emerges. The

oboes and cello play a drone

accompaniment in the cantus

cancrizans, and provide the

counterpoint in the nine canons

that comprise the body of the

piece.

The three cantus cancrizans are

in one tempo, the ritornelli

and canons in another. The music

of the first two ritornelli

is an abbreviated form of the ritornelli

between the canons, which are

the same throughout, as are the

odd-numbered canons, 1, 3, 5, 7,

9. The even-numbered ones, in

contrasting tonalities and, in

canons 4 and 6, new rhythms,

expose dramatic musical images

of the text. The beginnings of

canons 6 and 8 return to the

original tonality and melodic

form of the cantus cancrizans.

Canons 2 and 4 also derive from

the cantus cancrizans. Canon 4,

in a remote tonality, is marked

"in motu contrario" - in

the manuscript sketch Stravinsky

drew isobar lines showing the

relationships. The intervals are

inverted (the third becoming a

sixth, etc.), and jagged dotted

rhythms and harsh dissonances

are introduced programmatically.

Canon 6 employs still wider

leaps and more agitated

figurations in the cello; it

begins in C and ends in D sharp

major. The most affecting

harmonic event in the piece

occurs near the end of Canon 8

when, at the words "And rose

again on the third day,"

the tonal centre rises from C to

C sharp major.

Ricercar II marks a new

departure in Stravinsky's music

and, together with the Septet,

the Shakespeare Songs,

and the In Memoriam Dylan

Thomas that followed, he

entered new territory.

Babel [Heb: = confused]

in the Bible is the place where

Noah's descendants (who spoke

only one language) tried to

build a tower reaching up to

heaven to make a name for

themselves. For this

presumption, the speech of the

builders was confused, thus

ending the project. The story

was perhaps originally an

etiological tale explaining the

diversity of languages and

cultures, but owing to Israel's

experience of exile, it is now

interpreted as a polemic against

the presumption of Babylon,

which is Babel in Hebrew.

Stravinsky composed his cantata,

Babel, on words taken

from the first Book of Moses,

chapter 11, in April 1944. A

music publisher, Nathaniel

Shilkret, had commissioned a

number of composers to

contribute to a suite based on

early chapters in Genesis.

Schoenberg wrote the first

piece, called Prelude,

and Stravinsky the last, on the

subject of the building and

destruction of the tower of

Babel. The story is both

narrated, by David

Wilson-Johnson in this

recording, and sung by a male

chorus. The length of the piece

determined its form, which

begins with a passacaglia in

which a fugue serves as one of

the variations. The use of oboe

and harp in the orchestra

creates an oriental atmosphere

and the faster tempo and

rhythmic style of the

mid-section is an effectively

programmatic picture of the

scattering abroad of the people

for their "presumption."

Pasted to the flyleaf of the

lined notebook containing the

sketches for the Symphony of

Psalms is a newspaper

cut-out picture of Christ on the

Cross with spokes of light

emanating from His head and a

board above it inscribed in

Latin letters, "IMRI," which

means "Judahite" in the Hebrew

Bible; the base of the Cross

bears the caption "Adveniat

Regnum Tuum". The picture

disturbs us, partly because it

is devoid of artistic merit, a

specimen of Bondieuserie,

and partly because the Hebrew

Psalms are not the most

appropriate place for it.

The first notation for the Symphony,

the triplet upbeat figure

followed by the dotted half-note

(minim) and quarter-note

(crotchet) (bar 4 of [5]),

occurs near the beginning of the

orchestral allegro in the last

movement; the sketch is

harmonized and scored for

trumpets and horns, as in the

final score. The first dated

entries, "24-XII-1929, 6-I-1930"

(in the Julian calendar, which

Stravinsky used until his

American period), were intended

for the first movement. Among

the ten notations subsumed under

these dates are the ostinato

figure of minor thirds connected

by a major third, used in the

final score a minor-third

higher, and the octave leap

upward followed by a whole-step

down used in the choral chant at

[10], but here assigned to

horns. Three more pages of

sketches for the same Psalm

follow, dated 4 March, none of

them resembling the final form

of the music. (During January

and February Stravinsky had been

concertizing in Berlin, Leipzig,

Vienna, Bucharest, Budapest, and

Prague.)

On 10 March, he composed the

opening three bars of the last

movement, first in abbreviated

form and without the G in the

bass against the A flat for the

third syllable of "Alleluia",

then on seven staves, with

the G and as we know the setting

today. He wrote the Vulgate text

on the facing page, adding a

French translation in small

letters under the words "secundum

multitudinem magnitudinis"

- "selon la grandeur de son

magnificence" - for no

reason that I can discover

except to confound future

scholars, since it is impossible

that he did not know the meaning

of the Latin. The handwriting

here, exuberantly larger than

that for the text of Psalm 39,

suggests that composing the

"Alleluia" had been an epiphanic

experience for him. He drafted

the music from here to the end

of the movement in the order we

know, with a minimum of

correcting and rewriting and

none at all in the section for

full chorus before and through

the second "Alleluia".

After completing the movement,

27 April, he wrote it out in

condensed score form.

Resuming the composition with

the first movement on 10 May,

Stravinsky wrote the first

choral entrance over the

minor-thirds accompaniment

figure, but he interrupted his

work for concerts in Amsterdam.

In June he abandoned the first

movement once again and began

the second, writing out the

fugue subject a half-step lower

than we know it (starting on B

rather than C), an infrequent

instance of this in his

sketches, in which the pitch is

most often the same as in the

final score. On 21 June he

discovered the subject of the

choral fugue, combined it with

the instrumental subject in the

bass, and composed from there in

sequence to the end, which is

dated 17 July. After writing the

condensed score, he accompanied

Mme Sudeykina on a holiday to

Avignon, Vaucluse, and

Marseilles.

The composition of Psalm 39 was

begun in earnest on 29 July with

the writing of a Russian

translation under every word of

the text, conceivably in this

instance because he was seeking

further perspectives of meaning

in his mother tongue. On

completing the movement, he drew

a Russian-style cross in the

manuscript as an envoi and dated

it, in French, "15 August, The

Feast of the Assumption in the

Roman Church". Having composed

the piece in Nice and under the

same roof as his wife,

Catherine, he invited her to

attend the première, in

Brussels, on 13 December 1930.

On 14 December, after her

departure, Mme Sudeykina arrived

and Stravinsky, resuming the

other side of his divided life,

went with her to Amsterdam for

more concerts.

© Robert

Craft 2006

|

|

|

|

|