|

|

1 CD -

8.557503 - (c) 2006

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

Pulcinella

(1920) - Ballet in One Act

With Song

|

* |

|

36' 22" |

|

|

-

Ouverture

|

|

1' 56" |

|

1 |

|

-

Serenata: Mentre l'erbetta

(Tenor)

|

|

2' 29" |

|

2 |

|

-

(A) Scherzino; (B) Allegro; (C)

Andantino; (D) Allegro

|

|

6' 00" |

|

3 |

|

-

Allegretto: Contento

forse vivere (Soprano)

|

|

1' 42" |

|

4 |

|

-

Allegro assai

|

|

1' 55" |

|

5

|

|

-

Allegro (alla breve); Con

queste paroline (Bass)

|

|

3' 32" |

|

6 |

|

-

Largo: Sento dire no' ncè pace

(Terzetto)

|

|

1' 02" |

|

7 |

|

-

Chi disse cà la femmena

(Tenor)

|

|

0' 26" |

|

8 |

|

-

Allegro: Ncè sta quaccuna po'

(Soprano and Tenor)

|

|

0' 32" |

|

9 |

|

-

Presto: Una te fa la 'nzemprece

(Tenor)

|

|

1' 04" |

|

10 |

|

-

Larghetto

|

|

0' 25" |

|

11 |

|

-

Allegro alla breve

|

|

1' 11" |

|

12 |

|

-

Allegro moderato: Tarantella

|

|

1' 10" |

|

13 |

|

-

Andantino: Se tu m'ami

(Soprano)

|

|

2' 08" |

|

14 |

|

-

Toccata

|

|

0' 55" |

|

15 |

|

-

Allegro moderato: Gavotta with two

variations (Allegretto, Allegro)

|

|

3' 58" |

|

16 |

|

-

Vivo

|

|

1' 34" |

|

17 |

|

-

Minuet: Pupillette, fiammette

(Terzetto)

|

|

2' 14" |

|

18 |

|

-

Finale: Allegro assai

|

|

2' 09" |

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Fairy's Kiss (1928) |

**

|

|

42' 01" |

|

|

- Scene I

|

|

8' 05" |

|

20 |

|

-

Scene II

|

|

10' 48" |

|

21 |

|

-

Scene III

|

|

18' 32" |

|

22 |

|

-

Scene IV

|

|

4' 36" |

|

23 |

|

|

|

|

Pulcinella

Diana

Montague, Mezzo-soprano

Robin Leggate, Tenor

Mark Beesley, Bass

PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT

|

The Fairy's

Kiss

LONDON

SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England):

- 3 to 5 and 8 January 1995 (The

Fairy's Kiss)

- 31 January and 1 Febraury 1997

(Pulcinella)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Michael

Fine (The Fairy's Kiss)

Gregory K. Squires (Pulcinella)

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Simon

Rhodes (The Fairy's Kiss)

Michael Sheady (Pulcinella)

|

|

|

Assistant

Engineer |

|

David

Flowers (Pulcinella)

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557503 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 78' 23" | (c)

2006 | DDD

|

|

|

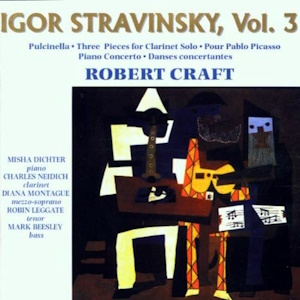

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Koch

International, Vol. III

| 3-7470-2 | 1 CD | (p)

1999 | DDD (Pulcinella)

Koch

International,

Vol. I |

3-7276-2 | 1

CD | (p) 1996

| DDD (The

Fairy's Kiss)

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

MusicMasters,

Vol. IV | 01612-67113-2

| 1 CD | (p) 1993 | DDD

(Agon)

|

|

|

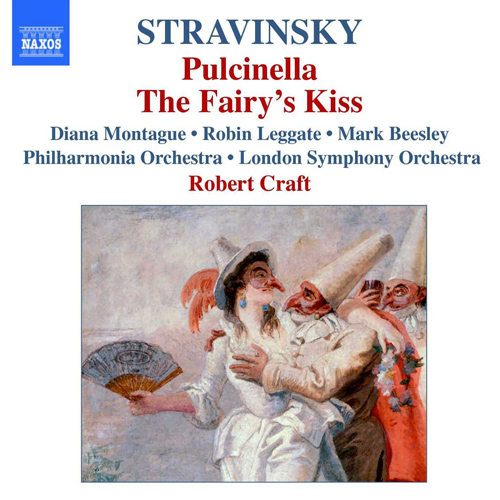

Cover |

|

Pulcinella in

Love, 1793 by Giovanni

Domenico Tiepolo (1727-1804)

(akg-images / Cameraphoto)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

1 CD -

3-7470-2 - Volume III

1 CD -

3-7470-2 - Volume III

(c) 1999 *

1 CD -

3-7276-2 -

Volume I

(c) 1996 **

|

Stravinsky’s

one-act ballet with song, Pulcinella,

is no mere re-working of music

by Pergolesi and other

18th-century Italian composers.

Instead he uses the originals as

a springboard for

experimentation, transforming

the music into a modern work by

means of quirky instrumentation

(for example, the jazzy

glissandos of the double-bass

solo), ostinato melodies, and

other 20th-century devices. The

ballet The Fairy’s Kiss,

at another extreme, is a largely

original composition. Stravinsky

greatly altered, developed, and

elaborated melodies from early

piano pieces and songs by

Tchaikovsky, expanding them into

sizeable ballet numbers to form

a continuous dance symphony.

Pulcinella (1920): Ballet in

One Act with Song

At the time of the first

performance of Pulcinella

the music was attributed to

“Igor Strawinsky d’après

Giambattista Pergolesi”. In fact

fewer than half of the pieces

that Stravinsky arranged for an

orchestra of 33 and three

singers were by Pergolesi

(1710–1736), whose entry in The

New Grove Dictionary of Music

and Musicians lists more

“spurious” and “doubtful”

creations than certifiably

authentic ones. As much material

comes from the trio sonatas of

the Venetian composer Domenico

Gallo (active c. 1730) as from

his Neapolitan contemporary.

Further, the score’s most

popular song, “Se tu m’ami,”

is by Parisotti, not Pergolesi.

The eighteenth-century copies

from which Stravinsky worked are

unsigned. Dyagilev told

Stravinsky that they had come

from a conservatory library in

Naples, but in actuality most of

them were transcribed in the

British Museum.

The libretto is in the hand of

Léonide Massine, who also

choreographed the ballet. The

scene is set in Naples and the

characters are taken from the Commedia

dell’Arte. Rosetta and

Prudenza respond to the

serenading of Caviello and

Florindo by dousing them with

water. A Dottore arrives

and chases the musical pair

away. Pulcinella enters, dances,

and attracts Prudenza, who tries

to embrace him. He rejects her.

Rosetta appears, chaperoned by

her father Tartaglia. She tells

him of her love for Pulcinella,

for whom she dances. He kisses

her, but is seen by Pimpinella,

his mistress, who becomes

jealous. Caviello and Florindo

re-enter in disguise, and

Florindo, jealous of Pulcinella,

stabs him. When the would-be

lovers leave, Pulcinella

cautiously gets up. Four little

Pulcinellas enter, carrying the

body of Furbo disguised as

Pulcinella. They place the body

on the floor. The Doctor and

Tartaglia enter with their

daughters, who are horrified. A

magician appears and revives the

corpse. When the fathers refuse

to believe the miracle, the

magician removes his cloak and

reveals himself as the real

Pulcinella. The revived corpse

is his friend Furbo. Pimpinella

enters but is frightened at the

sight of two Pulcinellas.

Florindo and Caviello return,

disguised as Pulcinellas, hoping

for more satisfaction in their

amorous pursuits. The confusion

caused by four Pulcinellas

prompts Furbo to resume his

disguise as magician. At the

end, the “Pulcinella” couples,

including Pimpinella and the

ballet’s eponymous hero, are

reunited and married.

Further to complicate the

distinction of identities, the

musical numbers do not

correspond to dramatic

situations, and the texts of the

vocal pieces - six of the seven

were borrowed from three

different operas - are unrelated

to the stage action. Some of

them, but not including Contento

forse vivere, from

Metastasio’s Adriano in Siria,

are in Neapolitan dialect.

Unpromising as all of this may

sound, the vocal pieces, one

aria for the bass, three for the

tenor, two for the soprano, one

duet, and two trios, seem to

turn the ballet into an opera

with a cohesive dramatic entity.

Stravinsky’s chief means of

distancing himself from the

eighteenth century is in the

instrumentation, which, almost

alone, transforms the music into

a modern work. The small

orchestra, with strings divided

into ripieni and a concertante

solo quintet, sounds like, but

never completely like, an

eighteenth-century ensemble. One

explanation for this is that the

trombone, employed in the

eighteenth century chiefly in

sacred or solemn music, is here

the instrument of a 1920s jazz

band, as the glissandos confirm.

Other modern instrumental

touches include the use of flute

and string harmonics, and string

effects such as flautando,

saltando, and the

non-arpeggiated double-stop

pizzicato. Still other

twentieth-century orchestral

novelties are the alternation of

string and wind ensembles for

entire pieces, as in,

respectively, the Gavotta

and the Tarantella, the

exploitation of wind-instrument

virtuosity - the whirligig

velocity of the flutes in the C

minor Allegro - and the

high ranges of the double-reeds

(the oboe’s high A, and a

bassoon tessitura fully a fifth

higher than would be expected in

eighteenth-century music). The

contrabass, too, in its

syncopated, jazz-style solo,

explores a higher altitude than

is normal in Old Music, but this

bass riff does not change a note

of the original. Indeed, what is

most surprising about the whole

of Pulcinella is how

closely Stravinsky follows his

melodic and figured-bass

skeletons, and how little he

alters the harmonic and melodic

structure. The bass vocal part

also requires an exceptional

high-register, which the vocal

score wrongly transposes an

octave lower.

The Fairy’s Kiss

Scene I - The lullaby in the

storm:

A mother, lulling her child,

struggles through a storm. The

Fairy’s attendant sprites appear

and pursue her. They separate

her from the infant and carry

him off. The Fairy herself

appears. She approaches the

child and enfolds him with her

tenderness. Then she kisses him

on the forehead and goes away.

Now he is alone. Country folk,

passing, find him, search in

vain for his mother, and, deeply

distressed, take him with them.

Scene II - A village fête:

A peasant dance is in progress,

with musicians on the stage.

Among the dancers are a young

man and his fiancée. The

musicians and the crowd

disperse, and, his fiancée going

away with them, the young man

remains alone. The Fairy

approaches him in the guise of a

gypsy woman. She takes his hand

and tells his fortune, then she

dances, and, ever increasingly,

subjects him to her will. She

talks of his romance and

promises him great happiness.

Captivated by her words, he begs

her to lead him to his fiancée.

Scene III - At the mill:

Guided by the Fairy, the young

man arrives at the mill, where

he finds his fiancée among her

friends playing games. The Fairy

disappears. They all dance; then

the girl goes with her friends

to put on her wedding veil. The

young man is left alone.

Scene IV

The Fairy appears, wearing a

wedding veil. The young man

takes her for his bride. He goes

towards her, enraptured, and

addresses her in the terms of

warmest passion. Suddenly the

Fairy throws off her veil.

Dumbfounded, the young man

realizes his mistake. He tries

to free himself, but in vain; he

is defenseless before the

supernatural power of the Fairy.

His resistance overcome, she

holds him in her power. Now she

will bear him away to a land

beyond time and place, where she

will again kiss him, this time

on the sole of the foot.

The Lullaby of the Eternal

Place:

The Fairy’s attendant sprites

group themselves in slow

movements of great tranquillity

before a wide décor representing

the infinite space of the

heavens. The Fairy and the young

man appear on a ridge. She

kisses him to the sound of her

lullaby.

The young man, of course, is

Tchaikovsky himself, the Fairy

his Mephistophelean muse. The

ending of Stravinsky’s homage to

his beloved forbear, one of the

most moving he ever wrote, is

rarely heard in ballet

performances at present. George

Balanchine’s abbreviated version

of the ballet concludes with the

peasants’ dance, which is in the

dominant, not the tonic, of its

key.

Commentaries on The Fairy’s

Kiss generally attempt to

establish parallels between

Pergolesi– Stravinsky and

Tchaikovsky–Stravinsky, but the

only exact one is that both

unwitting collaborators were

composers of the past. The

unique entirely original music

in Pulcinella is a short

bridge section and the

introduction to the Tarantella.

The Fairy’s Kiss, at

another extreme, is largely

original composition. Stravinsky

greatly altered, developed, and

elaborated melodies from early

piano pieces and songs by

Tchaikovsky, expanding them into

sizable ballet numbers forming a

continuous dance symphony. He

was so familiar with

Tchaikovsky’s stylistic

features, melodic, harmonic, and

instrumental, that he could

compose more Tchaikovsky

himself.

The sketches for The Fairy’s

Kiss do not contain a

single reference to sources in

Tchaikovsky, but perhaps more

than those for any other

Stravinsky work they confirm T.

S. Eliot’s dictum that “the mark

of the master is to be able to

make small changes that will be

highly significant”. In some

instances Stravinsky simply

changes Tchaikovsky’s tempo.

Thus the Scherzo humoresque

becomes the slow-tempo song at

the beginning of Scene III of

the ballet, and Tchaikovsky’s Allegretto

grazioso is wholly

transformed simply by being

played at half tempo: Stravinsky

retains the melody, rhythm, and

even the harmony of the

original. Stravinsky had a

genius for perceiving the

slow-tempo lyrical piece in the

fast-tempo one, the attractive

melody obscured by the dull

rhythm. The male dancer’s

Variation in Scene III changes

Tchaikovsky’s 3/4 Nocturne

to 6/8 and his monotonously

repeated eighthnotes (quavers)

to quarters (crotchets) followed

by eighths (quavers). I should

add that the ballet also

transposes the piece from A down

to G, but that, clearly, was to

accommodate the high notes of

the horn.

The most remarkable

transformation in The

Fairy’s Kiss is that of

the early song “Both Painful and

Sweet” into the Ballad

that concludes Scene II. In the

first five notes of the theme,

Stravinsky reverses the melodic

sequence E, C sharp, D natural,

to E, C natural, D sharp,

thereby changing A major to A

minor, while preserving the

ambitus. He also rewrites

Tchaikovsky’s rhythmic pattern

of quarter-note (crotchet) beats

and eighth-note (quaver)

offbeats to on-the-beat

triplets, with a rest replacing

the third note, as in the piano

and string ostinato in the first

movement of the 1945 Symphony;

this transforms the mood from

resolution to agitation. What

amazes us, however, is the

mileage that Stravinsky gets out

of this fragment in its

development, repeating it in

different octaves, progressively

slower tempos, and longer

note-values, until, at the end

of the scene, the bass clarinet

plays it slowly beneath six

ascending octave scales in the

flute, the first four notes of

which are in Stravinsky’s A

minor, the last four in

Tchaikovsky’s A major, a subtle

collaboration indeed.

Robert

Craft

|

|

|

|

|