|

|

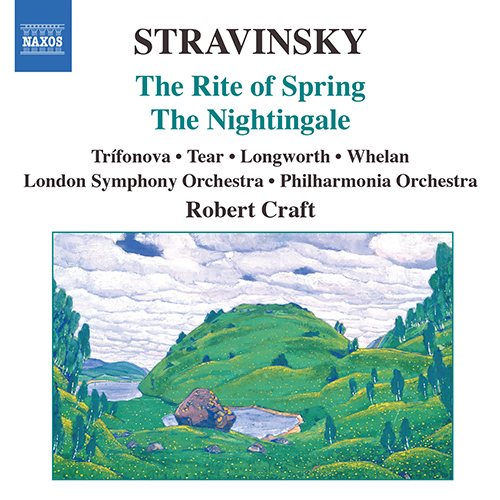

1 CD -

8.557501 - (c) 2005

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

The

Rite of Spring (1911-13)

|

* |

|

31' 58" |

|

|

First Part -

Adoration of the Earth

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Introduction

|

|

3' 19" |

|

1 |

|

-

The Augurs of Spring / Dances of the

Young Girls

|

|

3' 14" |

|

2 |

|

-

Ritual of Abduction

|

|

1' 19" |

|

3 |

|

- Spring

Rounds

|

|

3' 09" |

|

4 |

|

-

Ritual of the Rival Tribes

|

|

3' 10" |

|

5

|

|

-

Dance of the Earth

|

|

1' 18" |

|

6 |

|

Second Part - The

Sacrifice

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Introduction

|

|

3' 31" |

|

7 |

|

-

Mystic Circles of the Young Girls

|

|

3' 08" |

|

8 |

|

-

Glorification of the Chosen One

|

|

1' 37" |

|

9 |

|

-

Evocation of the Ancestors

|

|

0' 41" |

|

10 |

|

-

Ritual action of the Ancestors

|

|

2' 58" |

|

11 |

|

-

Sacrificial Dance

|

|

4' 34" |

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solovei

- The

Nightingale

(1908-9;

1913-14) -

Lyric Tale in Three

Acts after Hans

Christian Andersen |

**

|

|

44' 30" |

|

|

Scene 1 - The

forest at dawn

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Introduction |

|

3' 05" |

|

13 |

|

-

Fisherman

|

|

3' 32" |

|

14 |

|

-

Nightingale's Aria

|

|

3' 01" |

|

15 |

|

-

Chamberlain, Bonze, Cook, Courtiers

|

|

2' 50" |

|

16 |

|

-

Second Entrance of the Nightingale

|

|

0' 47" |

|

17 |

|

-

Chamberlain and Bonze

|

|

0' 24" |

|

18 |

|

-

Nightungale's Second Aria

|

|

0' 44" |

|

19 |

|

-

Chamberlain and Bonze

|

|

0' 52" |

|

20 |

|

-

Fisherman

|

|

1' 26" |

|

21 |

|

Scene 2 - The

porcelain palace of the Chinese

Emperor

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Prelude: Chorus and Orchestra |

|

1' 27" |

|

22 |

|

-

Cook

|

|

0' 20" |

|

23 |

|

-

Reprise of the Prelude

|

|

0' 22" |

|

24 |

|

-

Chinese March

|

|

3' 10" |

|

25 |

|

-

Chamberlain

|

|

0' 14" |

|

26 |

|

-

Song of the Nightingale

|

|

4' 12" |

|

27 |

|

-

The Japanese Envoys

|

|

1' 18" |

|

28 |

|

-

The Mechanical Nightingale

|

|

0' 59" |

|

29 |

|

-

The Emperor, Chamberlain, Courtiers

|

|

0' 59" |

|

30 |

|

-

Reprise of the Chinese March

|

|

0' 50" |

|

31 |

|

-

Fisherman

|

|

0' 59" |

|

32 |

|

Scene 3 - The

Emperor's Bedchamber

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Prelude

|

|

2' 43" |

|

33 |

|

-

Chorus of Ghosts, Emperor

|

|

1' 08" |

|

34 |

|

-

Nightingale |

|

2' 12" |

|

35 |

|

-

Death and the Nightingale

|

|

1' 29" |

|

36 |

|

-

The Nightingale's Aria

|

|

1' 25" |

|

37 |

|

-

Emperor and Nightingale

|

|

1' 41" |

|

38 |

|

-

Funeral Procession

|

|

1' 14" |

|

39 |

|

-

Fisherman |

|

1' 06" |

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

The rite of Spring

LONDON

SYMHPONY ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT

|

Solovei -

The Nightingale

Olga

Trífonova, Soprano

(The Nightingale)

Robert Tear, Tenor

(The Fisherman)

Pippa Longworth,

Soprano (The

Cook)

Paul Whelan, Bass-baritone

(The Emperor)

Stephen Richardson,

Bass (The

Chamberlain)

Andrew Greenan,

Baritone (The

Bonze)

Sally Burgess,

Alto (Death)

Peter Hall, Tenor

(Japanese Envoys 1 and

3)

Simon Preece, Bass

(Japanese Envoy 2)

London Voices

(Courtiers) by Terry

Edwards

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England):

- 1 to 4 July 1995 (The Rite of

Spring)

- 14 to 17 August 1997 (The

Nightingale)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Michael

Fine (The Rite of Spring)

Gregory K. Squires (The

Nightingale)

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Simon

Rhodes (The Rite of Spring)

Michael Sheady (The Nightingale)

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557501 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 76' 28" | (c)

2005 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Koch

International, Vol. II |

3-7359-2 | 1 CD | (p)

1996 | DDD (The Rite of

Spring)

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

MusicMasters,

Vol. X | 01612-67184-2 |

1 CD | (p) 1998 | DDD

(The Nightingale)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Sketch for

the Rite of Spring by

Nicolas Roerich (1874-1947)

(Art Gallery of Astrakhan,

Russia / The Bridgeman Art

Library) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

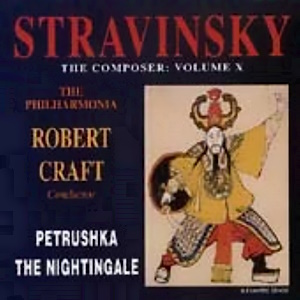

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

1 CD - 01612-67184-2 - Volume

X

(c) 1998 **

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

1 CD -

3-7359-2 - Volume II

1 CD -

3-7359-2 - Volume II

(c) 1996 *

|

‘May

whoever listens to this music

never experience the insult to

which it was subjected and of

which I was the witness in the

Théâtre des Champs-Elysées,

Paris, Spring 1913’, wrote

Stravinsky in 1968, of the

première of his Rite of

Spring. Written for a huge

orchestra to a setting of scenes

from pagan Russia, this

elemental ballet with its

vaulting, violent energy and

assymetrical rhythms almost from

beginning to end, has become a

major landmark of 20th century

music. Stravinsky’s orchestral

palette, different and

distinctive in every work, is

never more exotically colourful

than in his one act opera The

Nightingale, which is a

virtual catalogue of avian

imitations.

The Rite of Spring

“Composing The

Rite, I had only my ear

to help me. I heard and I

wrote what I heard.”- Igor

Stravinsky

Stravinsky

was inspired by a vision of The

Rite of Spring while

completing The Firebird.

His own title for it was Vesna

Svyashchénnaya, Holy

Spring, and he was never

happy with Léon Bakst’s more

memorable Le Sacre du

printemps, believing that

“The Coronation of Spring” was

closer to his original meaning.

Soon after the success of The

Firebird, Stravinsky

contacted Nicolas Roerich,

artist, archaeologist,

ethnologist, whom he met through

his nephew, a fellowpupil of

Rimsky-Korsakov, to share his

vision and to propose

collaboration in a “choreodrama.

“Who else could help me,” he

wrote to the St Petersburg

critic N. F. Findeyzen, “who

else knows the secret of our

ancestors’ close feeling for the

earth?” During the summer of

1910, however, Stravinsky’s

imagination was seized by Petrushka,

and when Dyagilev and Nijinsky

visited him in Lausanne to

discuss Vesna Svyashchénnaya,

they were astonished to hear

sketches for a puppet drama,

which so fascinated Nijinsky

that he persuaded Dyagilev to

postpone The Rite.

Stravinsky explained the

predicament to Roerich, but

urged him to continue with the

scenario, and also to design its

costumes and sets. The following

summer, after the triumph of Petrushka,

Stravinsky returned to The

Rite. Wanting him to see

the Princess Tenisheva’s

collection of Russian ethnic

art, Roerich asked Stravinsky to

meet him at Talashkino, her

country estate near Smolensk, to

plan the structure of the

ballet. En route to the creation

of this prehistoric work,

Stravinsky found himself sharing

the cattle car of a freight

train with a glowering,

slavering bull—a tauromachian

encounter that surely must have

heightened the young composer’s

atavistic imagination. The work

with Roerich, the plan of action

and the titles of the dances,

was quickly completed.

The Rite was conceived as

two equal and complementary

parts, The Adoration of the

Earth, which takes place

in daytime, and The

Sacrifice of the Chosen One,

which takes place at night. The

Introduction to Part One

represents the reawakening of

Nature. The curtain rises at the

end of it for the Augurs of

Spring, in which an old

woman soothsayer is accompanied

by a group of young girls. The

Ritual of Abduction

follows, then the Round-dances

of Spring, the Ritual

of the Two Rival Tribes,

the Procession of the Sage,

the Sage’s Kiss of the Earth,

and the Dance of the Earth.

Part Two, “The Sacrifice,”

or as the composer called it, “The

Great Offering,” begins

after an Introduction to “the

secret night-games of the

maidens on the sacred hill”. The

music accompanying these

mysterious rituals is quiet but

foreboding. After two

intimations of danger,

effectuated first by harsh

chords in muted horns, then by

muted horns and trumpets, and by

eleven savage drum beats, a wild

dance, the Glorification of

the Chosen One, erupts,

leading without pause to the Evocation

of the Ancestors, the Ritual

Dance of the Ancestors,

and the Sacrificial Dance.

The Sacrificial Dance

began with an unpitched notation

of the rhythmic germ written

during a walk with Ravel in

Monte Carlo in the spring of

1912. Pierre Monteux, who would

conduct the riotous première of

The Rite in Paris, 29th

May, 1913, was also in Monte

Carlo, and was present when

Stravinsky played the notyet-

completed score for Dyagilev on

the piano. Monteux wrote to his

wife: “Before Stravinsky got

very far I was convinced he was

raving mad.… The walls trembled

as he pounded away, occasionally

stamping his foot and jumping up

and down.”

In a state of exaltation,

exhaustion, and “with a terrible

toothache”, Stravinsky finished

the composition on 17th

November, 1912. Most of the

instrumentation in score form

was completed by the end of

March 1913. The vaulting energy

of the penmanship close to the

end reflects the force of his

drive to complete his work. The

note-stems, flags, and beams of

the wind instruments, followed

later by those of the strings,

incline steeply toward the

right. The bolder, larger notes

were evidently written at high

speed; simply to see them is to

be swept along with the feeling

that a powerful creation is

coming to its end. After the

last bar, Stravinsky signed and

dated the score 4th April, 1913.

His comment in the

upper-right-hand corner of the

final page translates as

follows:

May whoever

listens to this music never

experience the insult to which

it was subjected and of which

I was the witness in the

Théâtre des Champs-Elysées,

Paris, Spring 1913.- Igor

Stravinsky. Zurich, 11th

October, 1968.

The

Nightingale

Stravinsky had just completed

the first scene of The

Nightingale, a one-act

opera in three scenes, when

Dyagilev invited him to compose

The Firebird. He put the

opera aside for this ballet and

its successors, Petrushka

and The Rite of Spring,

then returned to the vocal work

between July 1913 and 28th

March, 1914. The première took

place in Paris on 26th May,

1914, conducted by Pierre

Monteux.

Stravinsky chose Hans Christian

Andersen’s tale partly because

music itself is the story’s

underlying subject, the power of

music not only to delight and to

move, but also to conquer death,

for The Nightingale is a

version of the Orpheus legend.

Stravinsky loved Andersen’s

stories - Le Baiser de la

fée is based on another -

and he managed to incorporate

some of Andersen’s fantastic

touches into the libretto. He

invited Stepan Stepanovich

Mitusov, a friend from the

Rimsky- Korsakov circle, to

compose the libretto with him.

Mitusov in turn consulted

Vladimir I. Belsky, the

librettist for three

Rimsky-Korsakov operas. On 9th

March, 1908, in Belsky’s St

Petersburg apartment, the

threesome fashioned the

scenario. The original draft of

scene one survives in

Stravinsky’s hand, and is

remarkably close to the final

version.

Scene One: The forest at

dawn. A fisherman is

mending his net and lamenting

his fate, in which his sole

consolation is the singing of

the Nightingale. The Nightingale

arrives and comforts the

Fisherman with its song. The

bird flies away at the approach

of a group of courtiers that

includes the Emperor of China’s

chief retainer (Chamberlain),

Bonze (Chaplain), and Cook, who

tells the Chamberlain that the

Nightingale sings at dawn in

these very trees, and that they

will now hear it. But just then

the Fisherman’s cow begins to

moo (upward glissandos in cellos

and basses) and everyone is

transported. The Fisherman

respectfully reveals that it was

his cow. The Cook confirms this,

but promises that the

Nightingale will start to sing

right away. In the meantime some

frogs croak (oboes). The

Chamberlain lets it be known

that the Emperor wants to see

the Nightingale at court, hear

it sing, and, in the event of

success, reward it with the

order of the golden slipper. The

Nightingale agrees and flies

down onto the Kitchen Maid’s

arm. - Exeunt omnes.

Scene Two: The porcelain

palace of the Chinese Emperor.

The Chamberlain appears and

chases everyone away, for the

Emperor is coming with his

entourage. The procession of the

Chinese Emperor (Chinese March).

The Nightingale is brought out,

the Emperor commands him to

sing, and when he does, the

Emperor’s eyes fill with tears.

Suddenly the Japanese

ambassadors arrive bearing a

gift from their Emperor, an

artificial nightingale. This is

wound up to sing. The offended

real nightingale flies away, and

the offended Emperor angrily

denounces it and bestows the

title “Court Singer on the

Left-hand Night Table of His

Highness” upon the artificial

nightingale. The Emperor orders

the mechanical nightingale to be

wound up again. It starts to

sing, but the music stops

abruptly, the cylinders turn,

hum, squeak, and the machine

falls silent. After a great

commotion, the disappointed

Emperor orders his followers to

their bedchambers. Everyone

retires.

Scene Three: The Emperor’s

Bedchamber. In the

foreground is an anteroom, from

which courtiers appear to ask

the Chamberlain whether the

Emperor has died. He lies on the

bed in spiritual torment. Death

sits upon him, watching him, and

the evil deeds he has committed

hover around him. He wants to be

comforted, calls for help, and

asks his artificial bird to sing

for him, although “there is no

winder to wind you up”.

Unobserved, the real nightingale

flies in from the garden,

perches on a windowsill, and

begins to sing. After one song

Death curls himself into a

shroud, moves away and

disappears, flying out the

window. As the Nightingale sings

on, the ghosts of the Emperor’s

evil deeds also vanish, and he

falls asleep. The Nightingale

finishes, and the Emperor

awakes. He sees the little bird

in the window and begs it to

stay in the palace forever. The

bird cannot accept the offer but

it promises to fly to the

Emperor to inform him of the

sufferings of the poor and of

all that goes on in his Great

Kingdom. The little bird flies

away. The courtiers, thinking

the Emperor already dead,

approach on tiptoe; but the

Emperor meets them, dressed in

royal robes and carrying his orb

and sceptre, which he clutches

to his heart. In the dawn light,

he says “good day” to the

dumbfounded courtiers.

Stravinsky’s orchestral palette,

different and distinctive in

every work, is never more

exotically colourful than in The

Nightingale, which is a

virtual catalogue of avian

imitations: tremolos, trills,

appoggiaturas, gruppetti,

string harmonics, pizzicato

glissandos, flautando and

ponticello effects, harp and

piano arpeggios, harp harmonics,

and the retuning of cello

strings to produce harmonics on

unusual pitches. The voice of

Death is introduced by four icy

high notes in the celesta, and

Death’s aria is accompanied by

the strangulated sound of a

cello playing a double

appoggiatura on the bridge of

the instrument in a high

register. After vanquishing

Death in their vocal duel for

the Emperor’s life, the

Nightingale sweetly sings to him

accompanied by mandolin and

guitar. In the “Chinese March,”

the mandolin doubling the soft

melody of the trumpet is a

previously unheard instrumental

colour, and the percussion

effects explore a greater range

than in any other Stravinsky

work except Les Noces.

Stravinsky also increases the

range of cymbales antiques

of The Rite of Spring from

two to six pitches, five of them

tuned to the “black-key”

pentatonic scale. The high

trumpet in D, another hold-over

from The Rite,

alternates with a second

instrument in E flat. The oboe’s

rapid two-note descending scale

figure (1), representing the

mechanical movement of the

Japanese nightingale, is yet

another brilliant instrumental

invention; no wonder Stravinsky

wrote next to his sketch for the

passage: “I am very pleased with

this”.

Robert

Craft

(1)

Played on this recording by

David Theodore.

|

|

|

|

|