|

|

1 CD -

8.557499 - (c) 2004

|

|

IGOR

STRAVINSKY | ROBERT CRAFT - Volume 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Igor STRAVINSKY

(1882-1971) |

Oedipus

Rex

|

* |

|

52' 21" |

|

|

-

Prologue

|

|

7' 51" |

|

1 |

|

-

Introducing Creon

|

|

7' 48" |

|

2 |

|

-

Introducing Tiresias

|

|

9' 56" |

|

3 |

|

-

Introducing Jocasta

|

|

11' 04" |

|

4 |

|

-

Introducing the Messenger

|

|

9' 05" |

|

5

|

|

-

Epilogue

|

|

6' 38" |

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Les

Noces

|

**

|

|

24' 10" |

|

|

-

Scene One

|

|

5' 11" |

|

7 |

|

-

Scene Two

|

|

5' 40" |

|

8 |

|

-

Scene Three

|

|

3' 02" |

|

9 |

|

-

Scene Four

|

|

10' 16" |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

Oedipus Rex

Edward

Fox, Speaker

Jennifer Lane, Mezzo-soprano

Martyn Hill, Tenor

Joseph Cornwell, Tenor

David Wilson-Johnson, Bass-baritone

Andrew Greenan, Bass

SIMON JOLY MALE CHORUS

PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA

Robert CRAFT

|

Les Noces

Alison Well, Soprano

Susan Bickley, Mezzo-soprano

Martyn Hill, Tenor

Alan Ewing, Basso-profundo

SIMON JOLY CHORALE

INTERNATIONAL PIANO QUARTET

TRISTAN FRY PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE

Robert CRAFT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded

at: |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England):

- June 2001 (Oedipus Rex)

- 8/9 January 2001 (Les Noces)

|

|

|

Live / Studio

|

|

Studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory

K. Squires

|

|

|

Production

Co-ordinator

|

|

Alva

Minoff

|

|

|

Production

Assistant

|

|

Phyllis

Lanini

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Arne

Akselberg (Oedipus Rex)

Mike Sheady (Les Noces)

|

|

|

Assistant

Engineer

|

|

Mike

Cox

|

|

|

Technical

Engineer

|

|

Dave

Forty

|

|

|

Naxos Editions

|

|

Naxos

| 8.557499 | 1 CD | LC 05537 |

durata 76' 31" | (c)

2004 | DDD

|

|

|

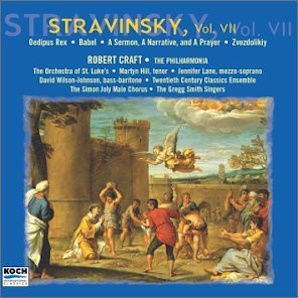

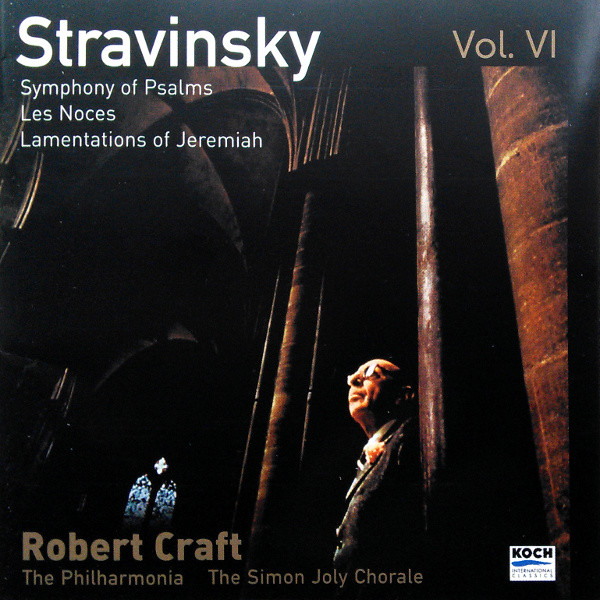

KOCH

(previously released) |

|

Koch

International, Vol. VII |

3-7477-2 | 1 CD | LC 06644 | (p)

2002 | DDD (Oedipus Rex)

Koch International, Vol. VI |

KIC-CD-7514 | 1 CD | LC 06644

| (p) 2002 | DDD (Les Noces)

|

|

|

MusicMasters

(previously released) |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

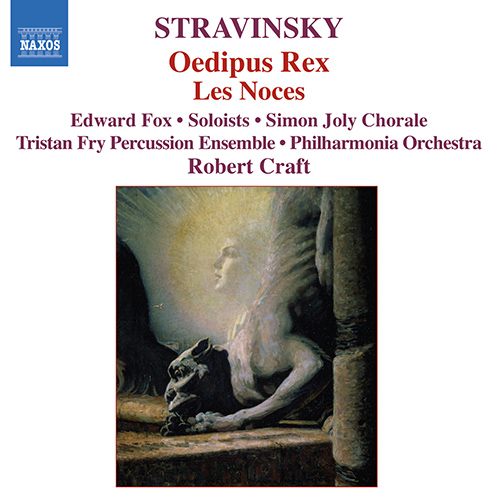

Cover |

|

The Sphinx

and the Chimera, 1906 by

Louis Welden Hawkins (1849-1910)

(Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France /

Bridgeman Art Library) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

MusicMASTERS

CLASSICS

Release (1991-1998)

|

KOCH

INTERNATIONAL

Release (1996-2002)

1 CD - 3-7477-2 - Volume VII

(c) 2002 *

1 CD - KIC-CD-7514

- Volume VI

1 CD - KIC-CD-7514

- Volume VI

(c) 2002 **

|

Oedipus

Rex, based on Sophocles’

tragedy, is an established

twentieth-century classic.

Employing a speaker, male chorus

and orchestra, it represents

Stravinsky’s 1920s

neo-classicism at its peak. Les

Noces, an amalgam of

ballet and dance cantata in four

scenes for solo voices, chorus,

four pianos and seventeen

percussion instruments, depicts

a Russian peasant wedding. One

of only two theatrical works by

Stravinsky to combine music with

a text in his mother tongue, Les

Noces is also his most

Russian work, in which ritual,

symbol and meaning on every

level are part of his direct

cultural heredity.

Oedipus

Rex • Les Noces

Stravinsky conducted the first

performance of Oedipus Rex

(1925-1927) in the Théâtre Sarah

Bernhardt, Paris, on 30th May,

1927, in a double bill with Firebird,

in which George Balanchine

danced the rôle of Kastchei.

Composers - Ravel, Poulenc, and

Roger Sessions among them - were

the first to recognize it as

Stravinsky’s most powerful

dramatic work and one of his

greatest creations. After

hearing Ernest Ansermet conduct

it in London, February 12, 1936,

the young Benjamin Britten noted

in his diary:

‘One of the

peaks of Stravinsky’s output,

this work shows his wonderful

sense of style and power of

drawing inspiration from every

age of music, and leaving the

whole a perfect shape,

satisfying every aesthetic

demand … the established idea

of originality dies so hard.’

Leonard

Bernstein may have been the

first to identify the principal

influence on the music:

‘I remembered

where those four opening notes

of Oedipus come from…

And the whole metaphor of pity

and power became clear; the

pitiful Thebans supplicating

before their powerful king,

imploring deliverance from the

plague … an Ethiopian slave

girl at the feet of her

mistress, Princess of Egypt …

Amneris has just wormed out of

Aida her dread secret … Verdi,

who was so unfashionable at

the time Oedipus was

written, someone for musical

intellectuals of the mid-’20s

to sneer at; and Aida,

of all things, that cheap,

low, sentimental melodrama.

[At the climax of Oedipus’ “Invidia”

aria] the orchestra plays a

diminished-seventh chord …

that favorite ambiguous tool [i.e.,

tool for suggesting ambiguity]

of surprise and despair in every

romantic opera … Aida!

… Was Stravinsky having a

secret romance with Verdi’s

music in those

super-sophisticated mid-’20s?

It seems he was.’ [Charles

Eliot Norton Lectures,

1973]

Bernstein

might also have mentioned the

debt to Verdi in Jocasta’s aria

and her duet with Oedipus. A

photograph of Verdi occupied a

prominent position on the wall

of Stravinsky’s Paris studio in

the 1920s, and on his concert

tours he would go out of his way

to hear Verdi operas, to the

extent of changing the dates of

his own concerts, as he did in

Hanover in December 1931 for a

performance of Macbeth.

In the early 1930s he wrote to

one of his biographers: “If I

had been in Nietzsche’s place, I

would have said Verdi instead of

Bizet and held up The Masked

Ball against Wagner”. In

Buenos Aires, in 1936,

Stravinsky shocked a journalist

by saying: “Never in my life

would I be capable of composing

anything to equal the delicious

waltz in La Traviata”.

Other influences besides Verdi’s

are apparent. The “Gloria”

chorus at the end of Act One,

the Messenger’s music, and the a

cappella choral music in

the Messenger scene are

distinctly Russian, but the

genius of the piece is in the

unity that Stravinsky achieves

with his seemingly disparate

materials.

Les Noces (Svadebka)

ranks high in the by no means

crowded company of indisputable

twentiethcentury masterpieces.

That it does not immediately

come to mind as such may be

attributable to cultural and

linguistic barriers, and to the

ineptitude, partly from the same

causes, of most performances,

for the piece can only be sung

in Russian, both because the

sounds of the words are part of

the music, and because their

rhythms are inseparable from the

musical design. A translation

that satisfied the quantitative

and accentual formulas of the

original could retain no

approximation of its literal

sense. For this reason

Stravinsky, never rigidly averse

to sacrificing the clarity of

sense for sound’s sake,

abandoned an English version on

which he had laboured in the

fall of 1959 and again in

December 1965. It is also the

reason, bizarre as it may seem,

that his own first recording of

Noces was made in English

(1934). No Russian chorus was

available in Paris at the time,

but in any case he abominated

the French version by C. F.

Ramuz, which requires numerous

changes and adjustments in the

musical rhythms.

Performances are infrequent as

well as inadequate. The four

pianos and seventeen percussion

instruments that comprise the

ensemble are not included in the

standard instrumentation of

symphony orchestras. Then, too,

the piece by itself is long

enough for only a short

half-programme, while the few

possible companion works, using

many of the same

instruments—Varèse’s Ionisation,

Bartók’s Sonata for Two

Pianos and Percussion,

Antheil’s Ballet mécanique

(an arrant plagiarism)—derive

from it too obviously as

instrumental example.

As a result of the obstacles of

language and culture, audiences

do not share in the full meaning

of the work, hearing it as a

piece of “pure” music; which, of

course, and as Stravinsky would

say, is its ultimate meaning.

But Stravinsky notwithstanding,

Svadebka is a dramatic

work, composed for the stage,

and informed with more meanings

on the way to that ultimate one

than any other opus by the

composer. The drama is his own,

moreover, and he is responsible

for the choice of the subject,

the form of the stage spectacle,

the ordonnance of the texts. Svadebka

is in fact the only theatrical

work by him, apart from the much

slighter Renard, that

combines music with a text in

his mother tongue, the only work

in which ritual, symbol, meaning

on every level are part of his

direct cultural heredity.

It is also the one Stravinsky

work that underwent extensive

metamorphoses. Svadebka

occupied his imagination

throughout a decade and, in

aggregate, took more of his time

than any other work of the same

length. The sketches, in

consequence, offer a unique

study of his processes of growth

and refinement. The reasons for

the long gestation are, first,

that Stravinsky several times

suspended work to compose other

music, which, in each case, left

his creative mind with altered

perspectives. Second, he was

creating something so new, both

musically, in its heterophonic

vocalinstrumental style, and in

theatrical combination and

genre, an amalgam of ballet and

dramatic cantata, that he was

himself unable to describe it.

“Russian Choreographic Scenes,”

his subtitle on the final score,

neglects to mention that the

subject is a village wedding and

that the four scenes depict the

ritual braiding of the Bride’s

tresses, the ritual curling of

the Groom’s locks, the departure

of the Bride for the church, and

the wedding feast.

Robert

Craft

|

|