|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 63462 2 - (c) 1999

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 2 in

B Major, Op. 14 "Dedication to

October" |

|

21' 22" |

|

| (Words by Alexander

Bezymensky) |

|

|

|

| -

Largo - allegro - moderato |

21' 22" |

|

|

| Symphony No. 3 in

E-flat Major, Op. 20 "The First of

May" |

|

33' 18" |

|

| (Words by Semion

Kisanov) |

|

|

|

Hamlet, Suite

Op. 32 *

|

|

21' 06" |

|

| Incidental music

to Shakespeare's tragedy |

|

|

|

| - 1. Introduction

and the night watch. Allegro

non troppo - Moderato - Poco

allegretto |

2' 29" |

|

|

| - 2. Funeral

March. Adagio |

1' 43" |

|

|

| - 3. Flourish and

Dance music. Allegro -

Allegretto |

2' 21" |

|

|

| - 4. Chase. Allegro |

2' 22" |

|

|

| - 5. Actor's

pantomime. Presto |

1' 26" |

|

|

| - 6. Procession. Moderato |

0' 58" |

|

|

| - 7. Musical

pantomime. Allegro |

1' 06" |

|

|

| - 8. The feast. Allegro |

1' 13" |

|

|

| - 9. Ophelia's

Song. Allegro |

1' 27" |

|

|

| - 10. Lullaby. Andantino |

1' 10" |

|

|

| - 11. Requiem. Adagio |

2' 07" |

|

|

| - 12. Tournament.

Allegro |

0' 59" |

|

|

| - 13. March of

Fortinbras. Allegretto |

1' 45" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43 |

|

66' 00" |

|

| - Allegretto poco

moderato |

27' 41"

|

|

|

| - Moderato con

moto |

9' 33"

|

|

|

| - Largo -

Allegretto |

28' 46"

|

|

|

Overture

to Erwin Dressel's Opera "Poor

Columbus", Op. 23 *

|

|

3' 31" |

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

Russian State

Academic Choir Cappella

(Opp. 14 & 20)

|

|

| Moscow

Philharmonic Orchestra (Op.

32) |

Stanislav Gusev,

Chorusmaster |

|

| Leningrad

Philharmonic Orchestra (Op.

23)

|

|

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1962 (Op. 32)

- 1983 (Op. 20)

- 1984 (Op. 14)

- 1985 (Op. 43)

Leningrad:

- 1979 (Op. 23)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Severin

Pazhukin (Opp. 14, 20 & 43),

Alexander Grosmann (Op. 32), Igor

Veprintsev (Op. 23) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 63462

2 | 2 CD - 76' 12" - 69' 43" | (c)

1999 | (p) 1962, 1980, 1985-1987 |

DDD/ADD* |

|

|

Note |

|

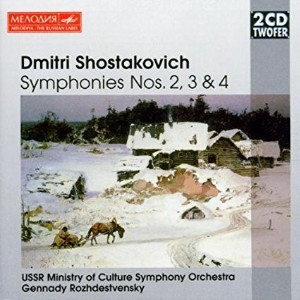

Front

cover: Wassili Dmitryevich

Polenov, "The Winter", 1880 |

|

|

|

|

A

miniature

"Hamletiade"

It was during the early

1980s that Gennady

Rozhdestvensky began his

complete recording of the

symphonies of Dmitri

Shostakovich (1906-1975), while

at the same time performing

apparently lesser works such as

indicental music and

soundtracks. Suddenly the early

symphonies appeared in a new

light: only now was it possible

to see that the formal

experiments of the Second, Third

and Fourth Symphonies were

inspired by the grand vision of

such pioneering directors as

Vakhtangov, Meyerhold and

Taïrov, all of whom sought to

renew the language of art

through the spirit of the

Revolution - what they called

"October in the theatre".

Shortly after the overwhelming

international success of his

First Symphony in 1926, the then

twenty-one-year-old composer was

commissioned to write a new

symphony by the music division

of the Soviet State Publishing

Company. Under the terms of his

contract, he was required to

write a piece commemorating the

tenth anniversary of the October

Revolution. The result was his

Second Symphony in B major op.

14, a work constructed along

traditional dramaturgical lines

with its idea of night giving

way to day - per aspera ad

astra. The opening is

dominated by a sense of sombre

chaos, after which musical

impulses start to form, held

together - as it were - by a

trumpet tune and finally

achoeving a sense of radiant

order. Unusual - at least for a

Soviet commission - is the

musical style, a style which,

with its linearity, atonality,

athematicism and arhythmical

structures, found the composer

very much abreast of his times.

At the start of the final

chorus, a siren is called on to

evoke the symphony's sphere of

reference, namely, the municipal

world of work. The use of such

sirens was by no means unusual

in works of this period, but

here it serves to signal a

particular tryth - that the

October Revolution banked almost

solely on the workers. To

dismiss the farmworkers as an

irrelevance was a basic error of

Communism and, indeed, of the

age as a whole, obsessed, as it

was, with the chimera of

industrialisation.

By contrast, Shostakovich

managed to avoid committing

another of the basic follies of

his age. His depiction of mass

actions (at the start of the

Largo, for example, the image of

crowds converging is conjured up

by means of scalar figures on

the strings rising up pianissimo

from their very lowest register)

never becomes a mere

glorification of the masses. On

the contrary, the middle section

of this movement (an Allegro

molto) is a trio for solo

violin, bassoon and clarinet, in

which intimacy and amity gain

the upper hand. Just as at the

beginning the strings rise up

from the depths, so in the final

chorus the voices emerge from

silence. The text is treated in

a declamatory manner and ends in

a brief spoken chorus. The first

part looks back to the past: "We

went and asked for work and

bread", while the second part

brings insight: "We understood

Lenin, that our fate has a name:

Struggle." In the final section

the work becomes openly

programmatical: "Look, the

banner, October, Communism and

Lenin." The straightforwardness

and serene objectivity of the

October Symphony were in stark

contrast to the romantic

euphoria and pomp of the actual

celebrations held to mark the

Revolution's tenth anniversary -

in this respect, nothing has

changed. First heard in

Leningrad in 1927, the work soon

vanished from Soviet concert

halls and was not restored to

the repertory until the end of

the 1960s.

The thirdt Symphony in E flat

major op. 30 ("The First of

May") received its first

performance on 21 January 1930,

only three days after

Shostakovich's first opera, The

Nose, had been unveiled.

The Leningrad Philharmonic was

conducted by Alexander Gauk.

Here was a work in which, to

quote the composer himself, "not

a single theme was repeated". A

single-movement piece, it ends

with a chorus inspired, in part,

by Beethoven's Choral Fantasy.

(The year 1927 was marked by

large-scale celebrations to

commemorate the centenary of

Beethoven's death.) Shostakovich

creates the atmosphere of a

street carnival, together with

the Dynamism and emotionalism of

popular speakers and the lively

throng of a milling crowd. It

was Meyerhold, after all, who

had argued that the true home of

art was the street.

There is something both

theatrical and cinematic about

this symphony, with its rapid

changes of musical perspective

and its abrupt fading in and out

of individual episodes, from

march to waltz and from

thrusting belligerence to a

cheeky grace and hesitant

groping forward. In the

Andante-Largo section, the Tuba

mirum interpolation and

wide-ranging dialogue between

trumpet on the one hand and the

dissenting voices of cellos and

basses on the other have an

oddly retardative effect. This

is no glittering celebration

that passes off with military

smoothness, but a barbed

occasion at best. This symphony,

too, was accused of formalism

and, like its contemporaries,

was not revived until after

1964, in the wake of the

rehabilitation of the composer's

early works.

Shostakovich's incidental music

for Hamlet was written

in 1932 for a production at

Mosvow's Vakhtangov Theatre. The

highly gifted and perceptive

director Nikolai Akimov

(1901-1968) saw the play as a

tragicomic struggle for survival

within a corrupt and despotic

system. In this he could appeal

to Shakespeare, although the

affinities with his own age and

country could hardly be

overlooked. His Hamlet, like

Shakespeare's, was no aesthete

but an overweight, beer-swilling

glutton who has faked the legend

of his father's ghost in order

to bolster his own position and

give him a hold over the new

king. Ophelia, too, has an eye

on the throne and is drowned

when legless with vodka. The

main character was the informer

Polonius, a parody of

Stanislavsky, bombastically

garrulous and completely above

all everyday cares. The

production was banned and all

that has survived is

Shostakovich's score.

The Hamler Suite for

small orchestra op. 32 is of

inspired simplicity, brevity and

lightness, a Russian answer to

Offenbach, suggesting glittering

ceremonies and raucous enjoyment

on the brink of the abyss. By

the end of 1929 Stalin had

succeeded in removing all his

political opponents from the

Party leadership and in 1930 the

Sixteenth Party Congress voted

for industrialisation along the

lines that he demanded. The

state's capacity for terrirising

its citizens could so easily

become a reality and be

celebrated with glittering pomp.

Societ Russia, too, was on the

brink of the abyss.

Shostakovich was confronted with

Shakespeare's tragedy for a

second time in his career when

his friend and patron, the

theatrical genius Vsevolod

Meyerhold, embarked on plans of

his own to stage the play in

Moscow. In his production,

Hamlet was to be played by two

different actors in order to

bring out the conflict between

the hero's tragic and comic

aspects. In this case, the

production did not even proceed

beyond the planning stage. More

than thirty years later,

Shostakovich wrote the

soundtrack for Grigori

Kozintsev's film version of the

play, a version that won an

award at the 1964 Venice Film

Festival and one, moreover,

which in spite of its

traditional characterisation, is

full of contemporary references.

By a curious coincidence,

Gennady Rozhdestvensky had

recorded Shostakovich's 1932 Hamlet

Suite only two years earlier, in

1962. The play still seemed to

have plenty to say to the Soviet

Union of the 1960s, as the

self-styled "Heirs of the

Vakhtangov Theatre" staged their

own Hamlet at this time,

with the legendary Vladimir

Vysotsky in the title role in

Yuri Lyubimov's modern-dress

productionat the Taganka

Theatre.

With his Fourth Symphony in C

minor op. 43 - composed between

September 1935 and May 1936 .

Shostakovich broke free from the

optimistic belief in the future

implied by his previous

symphonies. The old Bolshevik

governor of Leningrad, Sergey

Mironovich Kirov, had been

assassinated in 1934, allowing

Stalin to use his death as the

pretext for a campaign of

annihilating reprisals which on

this occasion increasingly

affected intellectuals. When his

music was placed on the Index of

Banned Composers in a Pravda

article in January 1936,

Shostakovich withdrew his score

and it was not until 30 December

1961 that it received its first

performance in Moscow under

Kyrill Kondrashin. Gennady

Rozhdestvensky gave its first

foreign performance when he

introduced it to Edinburgh

audiences in 1962.

In writing his Fourth Symphony,

Shostakovich broke with

symphonic convention. Here it is

no longer themes but motifs and

fragments of motifs and even

accompanying figures that

sustain the musical argument:

the seemingly insignificant

gives itself airs and is

invested with greater weight.

Here, too, Polonius supplants

the prince. Romantically

subjective outbursts of emotion

are eschewed and instead

everything is theatricalised -

just as in life itself. The

symphony opens marcatissimo

with three Oriental skirls on

everything but the bass

instruments, followed by

barbaric crescendos to quadruple

and quintuple forte, but

everything sounds mechanical,

like a juggernaut coasting

along, unstoppable, violent and

eerie. Perhaps it is Hamlet's

ghost - a ghost created by human

hand - that haunts this work as

well.

The opera Der arme Kolumbus

by Erwin Dressel (1909-1972)

received its first performance

in Kassel in 1928. In this

particular version of the story.

Columbus is no noble hero but an

adventurer lured by the lustre

of gold. Renamed Kolumbus,

the work received its Soviet

première at Leningrad's Maly

Theatre on 14 March 1929, with

additional music by

Shostakovich, who provided an

overture and finale.

Shostakovich was currently

working closely with the

company, preparing for the first

performance of his opera, The

Nose. His two additional

numbers provide, as it were, a

summation of the musical

mannerisms of his time, with

farting and groaning trombone

glissandi, figurations in the

flutes highest register

suggestive of spirited tightrope

walkers, the vulgar, penetrating

sound of the "singing saw" or

flexatone, bombastic

self-regarding solos, and

crowing marchlike episodes

followed by fleeting fugatos -

all the characteristics, in

short, of a figure like

Polonius. For a long time

Shostakovich's numbers for Kolumbus

were believed to be missing but

were rediscovered by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky and given a

concert performance at Tallinn

in 1977.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

GB)

|

|