|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 63461 2 - (c) 1999

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 10

in E Minor, Op. 93 |

|

53' 18" |

|

| - Moderato |

23' 18" |

|

|

| -

Allegro |

4' 22" |

|

|

| - Allegretto |

13' 02" |

|

|

| - Andante. Allegro |

12' 36" |

|

|

| Four Monologues

on Poens by Alexander Pushkin, Op.

91 (Orchestrated by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky) |

|

12' 46" |

|

| - 1. Fragmnent (Andante) |

5' 05" |

|

|

| - 2. What is my

Name for you (Allegro) |

2' 09" |

|

|

| - 3. In the Depth

of Siberian Ores (Adagio) |

3' 22" |

|

|

| - 4. Farewall (Allegretto) |

2' 10" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 11 in G Minor, Op. 103 "The

Year 1905" |

|

65' 08" |

|

| - The Palace

Square. Adagio |

17' 58"

|

|

|

| - January 9th. Allegro |

22' 26"

|

|

|

| - In Memoriam. Adagio |

9' 59"

|

|

|

| - Tocsin. Allegro

non troppo |

14' 45"

|

|

|

Finale

to Erwin Dressel's Opera "Poor

Columbus", Op. 23 *

|

|

4' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

Anatoli Safiulio,

bass (Op. 23)

|

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor |

USSR Ministry of

Culture Chamber Choir (Op. 23) |

|

|

Valeri Polyansky,

Chorusmaster |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1983 (Opp. 91 & 103)

- 1984 (Op. 23)

- 1986 (Op. 93) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Severin

Pazhukin (Opp. 93 & 23),

Edward Shakhnazaryan (Op. 103),

Igor Veprintsev (Op. 91) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 63461

2 | 2 CD - 66' 17" - 69' 42" | (c)

1999 | (p) 1983, 1985, 1987 |

DDD/ADD* |

|

|

Note |

|

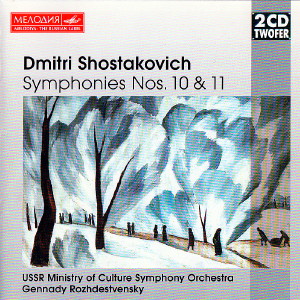

Front

cover: Natalya Gontcharova,

"Fresh-fallen Snow", 1911 |

|

|

|

|

Pushkin

as a Travelling

Companion

Shostakovich's Tenth

Symphony in E minor op. 93 was

written in the summer of 1953,

shortly after the death of

Stalin on 5 March 1953. It was

completed on 25 October and

performed for the first time in

Leningrad on 17 December under

Yevgeny Mravinsky. according to

the composer's own testimony, it

evokes the Stalinist era,

anathematising that age and at

the same time seeking to lay the

tyrant's ghost. The dictator

himself may have been dead, but

the repressive system that he

had created continued to exist;

his reign of terror was not yet

over; and people continued

suffer as before. The opening

Moderato owes its lamento-like

character to a quotation from

the composer's Eighth Symphony,

a work dedicated both to the

victims of state oppression and

to Mravinsky, who was a personal

friend of Shostakovich's. In the

second movement, pounding

rhythms, shrill breaks (here

used in the sense of short

unaccompanied passages in jazz)

and strident orchestra tutti

conjure up the picture of a

typical Asiatic despot.

(Shostakovich claimed that this

Allegro is a portrait of

Stalin.) The main theme is a

quotation from the scene in

Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov

in which the populace is herded

together and made to pay tribute

to its new ruler. Shostakovich

regarded this opera as an

exceptionally faithful and

intelligent account of the

relationship between rulers and

ruled. According to Mussorgsky

and Pushkin (it was on the

latter's historical tragedy of

the same name that Mussorgsky

based his libretto), nothing can

justify the blood guilt of those

who hold the reins of power. The

last two movements mark the

stages in an individual's life

when he is destroyed and

degraded but also when he

discovers his own sense of

identity. (Shostakovich gave

human shape to this particular

individual by means of his own

initials, D-Es-C-H, which can be

respelt using the German system

of notation as D-E flat-C-B.) It

was not only a question of

exorcising the evil spirit of

Stalinism but also of breaking

free from a state of immaturity

that may not have been his own

fault but which (to use a phrase

of Kant's) was none the less

"self-inflicted". In short,

Shostakovich sought to break out

of the vicious circle of

subjection, subordination and

blindness. In the final movement

the composer's signature

returns, now embedded in

shrill-sounding "circus music"

in a deafening unisono,

before the funeral music of the

recapitulation enters.

In March and April 1954 the

Union of Soviet Composers met to

consider how best to respond to

Shostakovich's Tenth Symphony,

and at the end of its three-day

session rebranded the composer

an "enemy of the people". By

now, however, his opponents -

the champions of "Socialist

Realism" - had lost their

position of power and it was not

long before it became clear that

the outlawed composer could

begin to look forward to his

rehabilitation.

Gennady Rozhdestvensky belongs

to the generation of Russians

who grew up in the shadow of the

Terror. He soon took the Tenth

Symphony into his repertory,

performing it for the first time

with the Moscow Philharmonic in

1955, when he was still only

twenty-four years old. He

approached this music mindful of

Bertolt Brecht's dictum that the

womb from which this

dictatorship crawled has not

lost its ability to bear

children.

Shostakovich's Four Romances op.

46 date from 1936/37 and were

his first settings of poems by

Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837).

Fifteen years later, in October

1952, he wrote his Four

Monologues op. 91 within the

space of a mere four days.

Another fifteen years were to

pass before his final setting of

a poem by Pushkin, Spring,

Spring op. 128, which

dates from August 1967. These

settings thus reflect three

stages in the composer's life

when, profoundly demoralised, he

turned to poetry in an attempt

to ward off despair. And in

Pushkin's verse he found the

supreme expression of

existential experiences of

transience, fame, artistic pride

and the consolation afforded by

love. Originally set for voice

and piano, these songs were

later orchestrated by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky and introduced to

Moscow audiences in 1982. The

soloist was Anatoli Safiulin.

The Monologues are less

emotionally charged than the

Romances but tend to be pensive

and restrained, ending on a note

of serene composure with no. 4,

"Farewell", an admission of the

transiet nature of our lives. In

"Fragment" (no. 1) the everyday

life of a Jewish family is seen

to symbolise a life beset by

fear. The father reads the

Bible, the mother prepares a

meal and the daughter cries over

an empty cradle.The bells in the

town begin to toll the midnight

hour, but sleep continues to

shun this outcast family. There

is a knock at the door and a

stranger enters. At this point

the monologue ends. For

Shostakovich and thousands of

his fellow Russuans, waiting to

be arrested by Stalin's

henchmen, who invariably arrived

at midnight or at dawn, this was

an elemental fact of life. "What

is my name for you?" (no. 2) is

an attempt on this poet's part

to assure himself of his own

innate merits and dignity,

qualities that no one else needs

by way of confirmation. "In the

depth of Siberian ores" (no. 3)

contains a clear political

message as well as a pointer to

Shostakovich's own life. His

grandfather and

great-grandfather were both of

Polish extraction and were

exiled to Siberia by the tsar on

account of their political

activities. Pushkin expresses

the certain knowledge that the

word "freedom" is noempty

illusion, lending the hackneyed

and much-abused term its ancient

dignity and meaning and taking

its part in the face of attempts

by those in power to subvert

that essential meaning.

The title of Shostakovich's

Eleventh Symphony in G minor op.

103 - "The Year 1905" - refers

to an historical event, the

massacre of peaceful

demonstrators in St Petersburg

on the orders of the tsar on

Bloody Sunday, 9 January 1905.

The events of 1956/57, when the

symphony was written, seemed to

the composer to invite this

parallel. Al the people whom the

victors refuse to honour. "It is

still the victor who writes the

history of the defeated," wrote

Brecht in Die Verurteilung

des Lukullus. "The

club-wielding victor distorts

the features of the man that he

clubs to death. The weaker man

quits the world, and all that

remains is a lie." Shostakovich

wrote his Eleventh Symphony in

the language and from the

perspective of the victims. This

emerges with particular force

from his treatment of his

themes, which are borrowed from

well-known folksongs and

revolutionary songs, including

thye funeral anthem You Fell

Victims in The Fateful

Struggle and the marching

songs Bravely in Step,

Comrades and The Girl

from Warsaw. In Soviet

Russia, these were officially

sanctioned songs designed to

uphold tradition. But just as in

real life the ideals of the

Revolution were misused and

distorted by the country's

rulers, so they now sound

shrill, harsh and dissonant in

Shostakovich's hands, before

seeming to cry out for help, but

returning in all their former

glory, as if these songs had a

soul.

The symphony's four movements

can be interpreted from the

standpoint of outward events.

The hollow fourths and fifths of

the opening movement ("The

Palace Square") suggest silence

and coldness - a large empty

space, while the mounting

tension of the second movement

("The Ninth of January") could

be an attempt to describe a

crowd of people gathering, with

the salvos on the percussion

that fill the sudden silence (a

fermata in the orchestra)

imitating the sound of gunshots.

In this apparently unambiguously

historical second movement,

however, Shostakovich has

included a self-quotation from

one of his Ten Choral Poems

on Revolutionary Texts of

1951, in which we encounter the

lines: "Look around you, Grandpa

Tsar, thanks to your servants we

have no lives left, we have

nothing at all". The third

movement ("In memoriam")

consists of an ostinato

variation on the funeral anthem

You Fell Victims in the

Fateful Struggle,

heard first on the violas and

suggesting the sort of music

that might accompany a funeral

procession, while the final

movement ("Tocsin"), in which

two revolutionary songs, Rage,

you Tyrants and The

Girl from Warsaw, are

combined together, might be

taken to depict the workers"

struggle against their

oppressors.

But things are not quite so

straightforward as this-

Shostakovich's symphony does not

simply set out to describe

historical events but examines

the impoverishment of the spirit

that is always bound up with

tyranny and that leads history

to repeat itself. "Our family

discussed the Revolution pf 1905

constantly," Shostakovich told

Solomon Volkov. "I think that it

was a turning point - the people

stopped believing in the tsar.

(...) But a lot of blood must be

shed for that. In 1905 they were

carting a mound of murdered

children on a sleigh. The boys

had been sitting in the trees,

looking at the soldiers, and the

soldiers shot them - just like

that, for fun. (...) I think

that many things repeat

themselves in Russian history.

(...) I wanted to show this

recurrence in the Eleventh

Symphony. I wrote it in 1957 and

it deals with contemporary

themes even though it's called

1905. It's about the people, who

have stopped believing because

the cup of evil has run over."

This loss of faith led

inexorably to violence and to

the constant recurrence of

violence.

The opera Der arme Kolumbus

by the German composer Erwin

Dressel (1909-1972) received its

first performance at Kassel in

1928. Shostakovich's finale to

the opera owes its existence to

the work's Soviet première at

the Maly Theatre in Leningrad in

1929, when the piece was staged

in modern dress. Shostakovich

was working closely with the

company at this time, helping to

prepare the first performance of

his own opera, The Nose,

and was asked to write the music

for a new epilogue and for the

cartoon film that was to

accompany it. Its title was

"What does modern America

represent?" In order to

understand the work, one needs

to know Shostakovich's comments

on the sequence of shots in the

film: "Armoured cruiser, ships,

airplanes", "The picture

contracts to a dot", "The dot

turns into a dollar",

"Gunshots", "The cost of the war

effort in the USA" and so on.

The next sequences appear under

the motto "Rejection of war. All

decide to take the road to

peace" and are accompanied by a

choral appeal: "Mir! Mir!

Mezhdunarodny mir" (Peace!

Peace! International Peace!).

For the sequence appearing

beneath the title "Arrival of

the Yankees", Shostakovich used

a trumpet tune that he was to

recycle in 1933 in the final

movement of his First Piano

Concerto op. 35.

This is an occasional

composition, an example of

functional music. For a long

time the score was believed to

be lost until it was

rediscovered by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky and given its

first performance in concert

form in the Great Hall of the

Leningrad Philharmonic on 1

February 1981.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

GB)

|

|