|

|

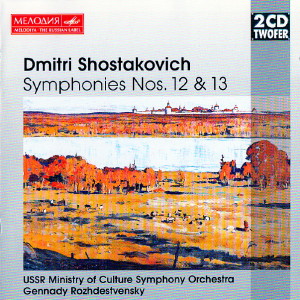

2 CDs

- 74321 63460 2 - (c) 1999

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 12

in D Minor, Op. 112 "The Year

1917" (Dedicated to the memory of

Vladimir Lenin) |

|

41' 35" |

|

- Revolutionary

Petrograd. Moderato - Allegro

|

13' 49" |

|

|

| -

Razliv. Allegro -

Adagio |

12' 39" |

|

|

| - Cruiser

"Aurora". L'istesso tempo -

Allegro |

4' 33" |

|

|

| - The Dawn of

Mankind. Allegro - Allegretto |

10' 34" |

|

|

Concerto for Violoncello

and Orchestra No. 1 in E-flat

Major, Op. 107 *

|

|

26' 09" |

|

| - Allegretto |

5' 53" |

|

|

| - Moderato |

10' 28" |

|

|

| - Cadenza. Allegro -

Allegretto |

5' 00" |

|

|

| - Allegro con moto |

4' 48" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 13 in B-flat

Minor, Op. 113 -

For Bass-Solo, Male Chorus and

Symphony Orchestra |

|

62' 55" |

|

| - Baby Yar. Adagio |

16' 46"

|

|

|

| - Humour. Allegretto |

8' 07"

|

|

|

| - In the Grocery. Adagio |

13' 50"

|

|

|

| - Fears.

Largo |

12' 07"

|

|

|

| - A

Career. Allegretto |

12' 05" |

|

|

| Eight Preludes, Op. 34 |

|

13' 23" |

|

| - No. 7 in A Major - Andante |

1' 31" |

|

|

| - No. 10 in C-sharp Minor -

Moderato non troppo |

1' 45" |

|

|

| - No. 22 in

G Minor - Adagio |

2' 28" |

|

|

| - No. 8 in F-sharp Minor -

Allegretto |

1' 04" |

|

|

| - No. 14 in E-flat Minor -

Adagio |

2' 21" |

|

|

| - No. 24 in D Minor - Allegretto |

1' 26" |

|

|

| - No. 17 in A-flat Major -

Largo |

2' 09" |

|

|

| - No. 5 in D Major - Allegro

vivace |

0' 39" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra (Op.

113, Op. 34)

|

Mikhail Khomister,

violoncello (Op. 107) |

|

| USSR RTV Large

Symphony Orchestra (Op.

112, Op. 107) |

Anatoli Safiulin,

bass (Op. 113) |

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor

|

Male Chorus of

the State Academic Russian Chorus

(Op. 113) |

|

|

Stanislav Gusev,

chorusmaster |

|

|

Alexander Suptal,

solo-violin (Op. 113) |

|

|

Olga Mnozhina,

solo-viola (Op. 113) |

|

|

Vasili Gorbenko,

solo-trumpet (Op. 113) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1968 (Op. 107)

- 1983 (Op. 34)

- gennaio 1984 (Op. 112)

- 1985 (Op. 113)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Igor

Veprintsev (Op. 112, Op. 107, Op.

34)

Severin Pazukhin

(Op. 113) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 63460

2 | 2 CD - 67' 57" - 76' 31" | (c)

1999 | (p) 1970, 1983, 1984, 1987

| DDD/ADD* |

|

|

Note |

|

Front

cover: Ilya Glazunov, "Rus", 1968 |

|

|

|

|

"For

Jew-haters I am a

Jew..." "For

Jew-haters I am a

Jew..."

Dmitri Shostakovich

(1906-1975) first conceived the

idea of writing a Lenin Symphony

as early as 1938, but it was not

until 1961 that he unveiled the

resultant piece at the

Twenty-Second Congress of the

Soviet Communist Party, a

congress at which the parallel

processes of de-Stalinisation

and Leninisation reached a

gruesome simultaneous climax.

Shostakovich openly admitted

that he had started out with one

particular portrait of Lenin in

mind but had reached a totally

different conclusion from the

one originally envisaged. What

had happened in the meantime?

With the political thaw of the

1950s, Shostakovich had assumed

a number of high-ranking state

appointments and, having walked

the corridors of power, had come

to see that there was no

essential difference between ine

ruler and the next. What was

true of Stalin was no less true

of his successors. According to

Shostakovich, they possessed "no

trace of ideology, no ideas, no

theories and no principles. They

exploited existing conditions on

an ad hoc basis in order

to tyrannise their subjects with

optimal effectiveness".

Narrow-minded, despotic, wilful

and pragmatic - such epithets

could sum up Khrushchev, too.

And so Shostakovich lost any

illusions that a wise leader

might actually exist. And he did

so when he recalled "The Year

1917", to quote the subtitle of

his Twelfth Symphony. Premièred

in Leningrad under Yevgeny

Mravinsky on 1 October 1961, it

was interpreted in East and West

alike as an act of compliance

with Communist doctrine and

either praised or criticised

accordingly. Gennady

Rozhdestvensky took it into his

repertory in 162.

Thematically speaking, the work

is circular in structure,

revolving, as it does, around

the ideas of manifestation,

resolution and return. There are

no musical contrasts, no

conflictual struggles, no traces

of parody. The opening movement

("Revolutionary Petrograd")

opens with the statement of a

motto theme that is also heard

in the following movements and

that is the only one to be

developed in full: all the

others remain mere fragments.

Razliv (the heading of the

second movement) was Lenin's

hideout in Karelia, where he

wrote many of his revolutionary

tracts. A salvo from the

armoured cruiser Aurora

(the title of the third

movement) gave the signal for

the capture of the Winter Palace

that is generally regarded as

the start of the October

Revolution. (To describe this

quasi-legendary event as the

"storming of the Winter Palace"

is to fly in the face of

history, as the Palace was not

defended.) The title of the

fourth movement, "The Dawn of

Humanity", can be taken as a

simple celebration of the

Revolution or as an invitation

to break free from the cult of a

leader like Lenin.

Shostakovich's own

interpretation is clear from a

self-quotation from his Second

Symphony of 1927, a work

dedicated "To Occtober": it was

still not possible to break free

from what Kant had called

"self-inflicted immaturity".

The First Cello Concerto in E

flat major op. 107 was written

in the summer of 1959 and

received its first performance

in Leningrad on 4 October 1959.

(Shostakovich's only other

contribution to the medium dates

from 1966.) The conductor was

again Mravinsky and the soloist

Mstislav Rostropovich, who also

gave the North American première

on 7 November 1959, when the

Philadelphia Orchestra was

conducted by Eugene Ormandy.

The concerto was soon described,

notentirely seriously, as a

"symphony with obbligato cello",

a description that emphasised

its dense thematic writing and

conceptual ambitions. For the

rest, however, this term is

completely misleading, inasmuch

as the piece is all about the

expression of individuality, an

individuality which, in keeping

with tradition, is championed by

the soloist who literally sets

the tone. It is the soloist,

after all, who opens the

concerto with a motto theme that

recurs in every movement and

that is both cheekily energetic

and at the same time harried.

With the exception of a horn in

F, Shostakovich gets by in this

piece entirely without brass

instruments, an abstemiousness

that is all the more surprising

in that grotesque capers on

trumpets and trombones had

become a hallmark of his style.

In the opening Allegro in E flat

major, the horn follows hard on

the heels of the cello, trying

its hand at the latter's

melodies and clearly proving

that when two people do the same

thing, the result is by no means

identical. In other words,

Shostakovich is here speaking

out against the current practice

of confusing legitimate

egalitarianism with the desire

to reduce the whole of mankind

to the lowest common

denominator. The second movement

is in A minor and opens with a

brief and mystical passage on

the strings suggestive of

nothing so much as a sarabande.

Here the horn has a quite

different function, and the c

ello reacts to its lushly

Romantic calls with a deeply

heartfelt melody that finally

dies away as though in the

furthest distance. All that

remains are signs that time

itself is slipping away on the

cello and celesta. The third

movement is a cadenza entrusted

to the soloist alone. One has

the impression that the soloist

ist brooding on the preceding

themes as he takes them up and

develops them in a technically

highly demanding passage

involving multiple stopping,

chords, polyphonic writing and

left-hand pizzicati. The final

movement is cast in the form of

a rondo, a harried orchestral

Allegro in which the soloist has

to struggle to maintain his

superiority. Gennady

Rozhdestvensky conducted the

piece for the first time in

Moscow in 1960, when the soloist

was Mstislav Rostropovich. The

present recording was made eight

years later, with Mikhail

Khomister as the soloist.

Shostakovich's Symphony no. 13

in B flat minor op. 113 for bass

soloist, bass chorus and

orchestra dates from 1962. A

setting of poems by Yevgeny

Yevtushenko (born 1933), it is

both a warning and a reminder of

Jewish pogroms both past and

present. To the surprise of many

onlookers, anti-Fascism and

anti-Semitism were by no means

mutually exclusive in Soviet

Russia. Fascism was officially

declared a morbid manifestation

of capitalism, and capitalism

alone. Anti-Semitism, by

contrast, continued to serve its

age-old function of providing a

scapegoat in times of crisis.

Thus there arose the paradoxical

situation whereby the Red Army

freed the world - and, hence,

the Jews - from Fascism at the

very time that the Soviet state

was hounding its own Jewish

citizens.

As a poet, Yevtushenko came to

prominence with his public

readings of his anti-Stalinist

poems and was enormously popular

with young audiences in the

early 1960s. Shostakovich sought

to ground his music in words

since, by his own admission,

words offered him "a certain

safeguard against absolute

stupidity". Many of hir earlier

symphonies had been

misunderstood or reinterpreted

and misappropriated by the

powers-that-be, and he was

determined that this would not

happen again. Like Yevtushenko,

Shostakovich was not Jewish, but

"for Jew-haters I am a Jew", to

quote from the symphony's

opening movement- Babi Yar is

the name of the ravine near Kiev

where 34,000 local Jews were

murdered by German soldiers from

the SS and Wehrmacht on

29 September 1941. Words and

music recall different stages in

the annihilation of the Jews

from ancient Egypt to

20th-century Soviet society.

Included here are an allegretto

episode associated with Anne

Frank and a scherzo that

suggests nothing so much as a

caricature of racism and

nationalism. The second movement

is headed "Humour", in this case

the folk wit before which even

the greatest dictator is bound

to capitulate, while the third

movement ("In the Store") is an

Adagio that tells of the heroism

of women, of their twofold

occupations at home and at work,

their tolerance of official

bullying and the brutalisation

of morals. In the fourth

movement, "Fears", Shostakovich

conjures up a sense of torment

in a cold and glassy Largo. And

in the final movement

("Career"), the lives of artists

and scholars are passed in

review: careers that are

dedicated to the pursuit of

power are rejected, while those

devoted to compassion receive

the aythor's blessing. Existing

values are overturned in a kind

of Last Judgement. Celesta and

bells remind us of death and of

the irrevocable passage of time.

The Thirteenth Symphony was an

appeal for tolerance. Above all,

however, it asked probing

questions as to the why and

wherefore of materialistically

orientated, ideologically

indocrinated Soviet society and

expressed a sense of concern

about basic values. This meaning

was immediately clear to the

audience at the work's

triumphant first performance in

Moscow, under Kyrill Kondrashin,

in December 1962, hence the fact

that for the next few years all

further performances were banned

by the authorities. Gennady

Rozhdestvensky conducted it for

the first time in Chicago,

although not until 1985 was he

able to record it in Moscow.

Shostakovich was also a

brilliant pianist and at the

beginning of his career wrote a

number of works for his own in

the concert hall. The very title

of his 24 Preludes op. 34 of

1932/33 clearly recalls their

model, Johann Sebastian Bach. It

was, in fact, by no means an

obvious model to choose, in that

the Thomaskantor - a

quintessentially German composer

of essentially sacred works -

was out of favour with the

Russian cultural authorities,

and it was not until many years

later that Shostakovich could

officially mark the bicentenary

of Bach's death with his

pianistic masterpiece, his 24

Preludes and Fugues op. 87 of

1950/51.

Shostakovich's op. 34 Preludes

immediately caught the attention

of such internationally

acclaimed pianists as Heinrich

Neuhaus, Lev Oboroin and Artur

Rubinstein, all of whom took the

piece into their repertory. As

with almost all of

Shostakovich's works from this

period, these 24 Preludes

present a paradox, combining, as

they do, apparently

irreconcilable opposites, being

both poetic and prosaic in

expression, mischievously witty

and daintily playful, profoundly

constructivist and at the same

time pared down to their barest

essentials. Their expressive

precision, the transparency of

their part-writing and the

colourful nature of their

melodic and harmonic writing

immediately invited

transcriptions and

orchestrations. A violin

transcription by Dmitri

Tsyganov, the first violinist of

the Beethoven Quartet (itself

the dedicatee of the composer's

Twelfth String Quartet of 1968),

proved particularly popular, in

addition to earning

Shostakovich's approval. The

version heard here is by the

internationally acclaimed

Croatian composer and pupil of

Messiaen, Milko Kelemen (born

1924), who orchestrated eight of

these Preludes and assembled

them in the form of a suite.

The Seventh Prelude in A major

serves as an andante

introduction, its pastoral tone

underscored by solo writing for

the cello. The combination of

gracefulness, cheekiness and

naivety in the C sharp minor

Prelude no. 10 are brought out

in the surprisingly prominent

piano part in Kelemen's

transcription. One of

Shostakovich's most popular

pieces, this was also one of the

composer's own personal

favourites and, as such, a piece

that he frequently played. In

no. 22 in G minor, two voices

enter into dialogue in a

contemplative, pastoral Adagio

that stands in stark contrast to

the polka-like strains of the

Prelude no. 8 in F sharp minor,

with bassoon and muted trunpet

tripping the light fantastic in

Kelemen's transcription. The

Prelude no. 14 in E flat minor

provides the cycle with its

tragic climax, an Adagio that

Leopold Stokowski, too, was

later to orchestrate and include

in his concert programmes.

Shostakovich himself

instrumented in 1943 and

incorporated it into his

soundtrack for the film Zoya.

The D minor Allegretto (no. 24)

proves a wide-ranging piece in

Kelemen's orchestration,

extending, as it does, from

braying brass to the ethereal

sounds of the celesta. With its

pianissimo and espressivo

amoroso, the Largo of no.

17 in A flat major is a serenely

carefree piece that becomes a

kind of moto perpetuo in

the ensuing Allegro vivace (no.

5 in D major) that brings the

cycle to its fleet.footed close.

Kelemen's suite received its

forst performance in Soviet

Russia in 1982. The conductor

was Gennady Rozhdestvensky.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

U.K.)

|

|