|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 59058 2 - (c) 1998

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| "Tale of the

Priest and his Servant Balda",

Suite, Op. 36 |

|

10' 00" |

|

| - 1. Overture |

1' 28" |

|

|

| -

2. Procession of Obscurantists |

1' 09" |

|

|

| - 3.

Merry-Go-Round |

1' 51" |

|

|

| - 4. Bazaar |

1' 26" |

|

|

| - 5. Popovna's

Dream |

2' 41" |

|

|

| - 6. Final |

1' 25" |

|

|

| 2

Fables after Ivan Krylov, Op. 4 |

|

7' 30" |

|

| - 1. The Dragonfly

and the Ant |

2' 48" |

|

|

| - 2. The Ass and

the Nightingale |

4' 42" |

|

|

| 6

Transcriptions for Orchestra |

|

17' 58" |

|

| - 1. Domenico

Scarlatti: Pastorale, Op. 17 |

3' 42" |

|

|

| - 2. Domenico

Scarlatti: Capriccio, Op. 17 |

3' 38" |

|

|

| - 3. Ludwig van

Beethoven: "Es war einmal ein

König..." |

2' 32" |

|

|

| -

4. Johann Strauss II: Vergnügungszug |

2' 10" |

|

|

| - 5. Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov: "Ya dolgo zhdal

tebya" |

2' 36" |

|

|

| - 6. Vincent

Youmans: "Tahiti Trot" ("Tea for

Two"), Op. 16 |

3' 20" |

|

|

| Scherzo for

Orchestra in F-sharp Minor, Op.

1 |

|

5' 02" |

|

| Theme with

Variations in B Major, Op. 3 |

|

15' 32" |

|

| Scherzo for

Orchestra in E-flat Major, Op. 7 |

|

3' 36" |

|

"Alone",

Suite from the Film Score, Op. 26

(Orchestration by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky)

|

|

12' 39" |

|

| - 1. Part I |

4' 19" |

|

|

| - 2. Part II |

2' 18" |

|

|

| - 3. Part III |

6' 02" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| "Big

Lightning", Excerpts from the

Comic Opera |

|

16' 53" |

|

| - 1. Overture - 2.

Scene |

5' 01"

|

|

|

| - 3. Architect's

Song |

4' 03"

|

|

|

| - 4. Scene

(Yankee) |

1' 40"

|

|

|

| - 5. Matofel's Song |

2' 18"

|

|

|

| - 6. Selyan's Song |

1' 04" |

|

|

| - 7. Duet |

0' 47" |

|

|

- 8. Procession of

the Models

|

2' 01" |

|

|

| "Adventures

of Korzinkina", Suite, Op. 59 |

|

9' 14" |

|

| - 1. Overture |

0' 31" |

|

|

| - 2. March |

1' 55" |

|

|

| - 3. Chase |

2' 45" |

|

|

| - 4. Restaurant

Music |

2' 04" |

|

|

| - 5. Intermezzo |

0' 34" |

|

|

| - 6. Finale |

1' 26" |

|

|

| Suite

No. 1 for Jazz Band |

|

8' 36" |

|

| - 1. Waltz |

2' 41" |

|

|

| - 2. Polka |

1' 54" |

|

|

| - 3. Foxtrot |

4' 02" |

|

|

| Romance on

Pushkin's Poem "Spring,

Spring...", Op. 128 |

|

2' 03" |

|

| "Golden Hills",

Suite, Op. 30a |

|

22' 59" |

|

| - 1. Introduction |

1' 27" |

|

|

| - 2. Waltz |

5' 12" |

|

|

| - 3. Fugue |

8' 34" |

|

|

| - 4. Funeral March

- 5. Finale |

7' 46" |

|

|

| "The Bug",

Excerpts from the Play by

Mayakovsky, Op. 19 |

|

10' 07" |

|

| - 1. March |

2' 06" |

|

|

| - 2. Intermezzo |

3' 36" |

|

|

| - 3. Scene on the

Boulevard |

2' 30" |

|

|

| - 4. Final March |

1' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

Chamber Choir of

the Moscow Conservatory (Op.

4: n.2) |

|

| USSR Symphony

Orchestra (Op. 36, 6

Transcriptions for Orchestra: n.

5) |

USSR Ministry of

Culture Chamber Choir ("Big

Lightning"), Op. 59: 6) |

|

| USSR Symphony

Orchestra Soloists Ensemble (Op.

26)

|

Valeri Polyansky,

chorusmaster |

|

| Moscow

Philharmonic Orchestra (Op.

4: n.6, 6 Transcriptions for

Orchestra: n. 4)

|

Galina Borisova,

soprano (Op. 4: n.1) |

|

| Leningrad

Philharmonic Orchestra (6

Transcriptions for Orchestra: n.

6)

|

Alla Ablaberdyeva,

soprano (6 Transcriptions

for Orchestra: n. 5) |

|

| Soloists Ensemble

(6 Transcriptions for

Orchestra: nn. 1-3, Suite No. 1)

|

Evgeni Nesterenko,

bass (6 Transcriptions

for Orchestra: n. 3, Op. 128) |

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor

|

Yuri Friov, tenor

("Big Lightning") |

|

|

Victor Rumyantsev,

tenor ("Big Lightning") |

|

|

Nikolai Myasoedov,

baritone ("Big Lightning") |

|

|

Nikolai Konovalov,

bass ("Big Lightning") |

|

|

Anatoly Obraztsov,

bass ("Big Lightning":

nn. 2-3) |

|

|

Natalia Kordalina,

piano (Op. 59) |

|

|

Mikhail Muntyan,

piano (Op. 59) |

|

|

Nicolai Stepanov,

hawaiien guitar (Op. 30a: n.2) |

|

|

Ludmila Golub,

organ (Op. 30a: n.3) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1979 (Op. 36, Op. 4, 6

Transcriptions for Orchestra nn.

1-5)

- 1982 (Op. 1, Op. 3, Op. 7, Op.

26)

- 1984 ("Big Lightning", Op. 59)

- 1985 (Suite No. 1, Op. 128, Op.

30a, Op. 19)

Leningrad:

- 1979 (6 Transcriptions

for Orchestra n. 6) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Igor

Veprintsev (Op. 36, 6

Transcriptions for Orchestra nn.

1-4, Op. 26, Suite No. 1, Op. 19)

Pyotr Kondrashin (Op. 4 n.1, 6

Transcriptions for Orchestra n.

5)

Severin Pazukhin (Op. 4

n.2, Op. 1, Op. 3, Op. 7, "Big

Lightning", Op. 59, Op. 129, Op.

30a) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 59058

2 | 2 CD - 73' 15" - 70' 34" | (c)

1998 | (p) 1980, 1983, 1984, 1987,

1991 | ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

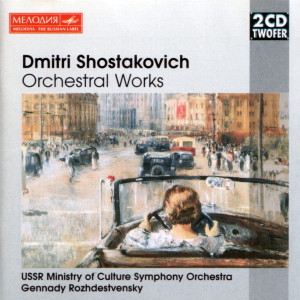

Front

cover: Yuri Ivanovich Pimenov,

"The new Moscow", 1937 |

|

|

|

|

A

must Shostakovich

connoisseurs

The works selected for the

two CDs run from opus 1 of 1919,

a Conservatory exercise by the

13-year-old Shostakovich, to a

work written euìight years

before his death, opus 128. The

concentration is on works from

the Twenties and Thirties,

discovered and in part

reconstructed by Gennady

Rozhdestvensky. From the early

Eighties they were recorded by

Melodiya in the series From

manuscripts of various years.

They are a minor sensation for

musiclovers, a must for

Shostakovich connoisseurs.

The Tale of the priest and

his servant Balda opus 36

was an animated film executed in

1933/35 by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky,

for which Shostakovich composed

the music. The film stock was

destroyed during the war and it

was not until 1978 that

Rozhdestvensky was able to

reconstruct the music from

handwritten drafts of the score,

compiling a concert suite

premiered in 1979. The complete

film music was revived as a

children's opera in 1980 at the

Maly Theatre in Leningrad. In

1986 it was given its first

German performance, to a text

prepared by me from the

original, at the Staatsoper in

Berlin. The story follows

Alexander Pushkin's novel of the

same name. The servant Balda is

looking for work, the village

priest is looking for a servant.

They meet in the bazaar (1:4,

Bazaar). They strike a deal. In

return for ayear's work, the

servant demands the right to

punch his master three times on

the nose. The year passes. The

servant eats enough food for

four and does the work of seven,

always staying cheerful (1:3,

Balda turns the Carousel

to the joy of young and old).

The priest's daughter falls in

love with him (1:5, The

priest's daughter's dream).

Towards the end of the year the

priest gets cunning and sends

his servant to the devil (1:2, Devil's

procession) to claim the

tribute that has been denied,

knowing full well that no

traveller returns from thence.

The servant innocently walks

into the trap but succeeds in

outwitting the devil and

returning to the village with

the tribute, whereupon he takes

his wages, knocking all sense

out of the priest's head. The

score contains all the best

elements of Shostakovich's early

music with its strong emphasis

on instrumental colour. The

servant comes in with heavy

kettledrum tread, heroic

trumpets and emotional trombone

strains, while the priest

squeaks away in the piccolo's

highest registers and gives out

pathetic clarinet quacks and the

priest's daughter dreams to the

homespun common chords of a

guitar and lulls herself with

fashionable saxophone warblings;

the devils surround themselves

with a spooky rattle of

xylophones, flitting in on wild

glissandos, and the carousel

turns to the sweetly ironic

tones of a music-box (flute,

clarinet, oboe and bassoon).

The Two Krylov Fables opus 4 for

mezzosoprano or women's choir

and orchestra were written in

1922 while Shostakovich was

attending the Conservatory and

are classic examples of Russian

"Kryloviana", a form to which

anton Rubinstein and Vladimir

Rebikov had already contributed.

According to Rozhdestvensky,

however, "no-one delved as deep

into Krylovian irony as the

18-year-old Shostakovich". Grasshopper

and Ant (1:7): the

grasshopper sings all summer

through and makes no provision

for the morrow. In winter she is

racked by unger. She asks

Neighbour Ant for food and is

turned away. The grasshopper

argues that in the summer she

entertained the ant with her

song. "Then now you can dance",

the ant tells her. The

mezzo-sopranoìs high register

provides the grasshopper's

voice, the low register the

ant's, in a wonderfully

economical use of vocal

resources. - The ass declares

himself a judge of the

nightingale's song (1:8, Ass

and Nightingale). The

singer shows off her skills in a

springlike song full of trills

and blossoming melody

(Rimsky-Korsakov through and

through). All are silent, even

the winds are subdued. Then we

hear the monotonous notes of the

ass, who upbraids the singer and

recommends lessons from the

cockerel. Shocked, the

nightingale flies off for ever:

"God preserve us from such

judges". At the tender age of

18, Shostakovich foretold his

own future. He too was subject

to the verdict of asinine

judges. Only - he never managed

to fly away from them. The

premiere was held in Moscow in

1974, a year before

Shostakovich's death, under the

baton of Rozhdestvensky.

Shostakovich was a master of

instrumentation. In 1928, he

adapted two harpsichord sonatas

by Domenico Scarlatti (opus 17)

for small wind ensemble and

timpani, masterpieces full of

wit and charm premiered by

Nikolay Malko in Leningrad the

same year. - Beethoven's Song

of the Flea had been

orchestrated by Stravinsky in

1909 at the request of Fyodor

Shalyapin and successfully

premiered in one Ziloti's

concerts in St Petersburg. The

parable of the flea tells how a

flea is appointed minister by

royal edict, brings all his

friends and relations to court

and makes life a misery for all

the people around them, who must

suffer their fate willy-nilly.

This story was as topical as

ever during the Communist era.

At the request of Yevgeny

Nesterenko, Shostakovich

rearranged the work. It was one

of his last compositions. -

Johann Strauss's 1864 Excursion

Train written in honour of

the new railway line from Vienna

to Grinzing was arranged in 1940

for the Maly Opera Theatre of

Leningrad to accompany a dance

interlude in a production of

Rimsky-Korsako's Romance "I

waited for you" is a student

work documenting the

fifteen-year-old's ability to

imitate the style of his

teachers, notably Rimsky. The

punch-line - "You did not

come" - packs more of a

punch, however, than the

preceding generation would have

given it. - The transcription of

the foxtrot Tea for Two

from the musical No No Nanette

by Vincent Youmans was

remarkably popular under its

name of Tahiti Trot. It

was the conductor Nikolay Malko

who was the guilding spirit

behind this masterstroke:

"During one of our concert tours

through the Ukraine (1928)

Mitya" - affectionate form of

Dmitri - "was listening to a

record of the Tahiti Trot.

I said to him: ' Dear Mitya, if

you are really so clever as they

say, then go into the next room,

write out the number from memory

and orchestrate it, and I will

perform it. I will give you -

one hour.'" Forty-five minutes

later, the story goes,

Shostakovich gave Malko the

finished score. And Malko duly

premiered it in Leningrad in

1928.

The Scherzo for Orchestra in

F sharp minor op. 1

(1919), the Theme and

Variations in B major op.

3 (1922) and the Scherzo for

Orchestra in E flat major

op. 7 (1924) are Shostakovich's

earliest orchestral works,

unearthed from the archive by

Rozhdestvensky. - Written in

1919 in his first few month at

the Conservatory, the op. 1 Scherzo

is dedicated to Maximilian

Steinberg (1883-1946), who

taught Shostakovich composition,

harmony and instrumentation.

(Rozhdestvensky conducted the

premiere in Tallinn in 1977.)

Shostakovich returned to the

first theme of his opus 1 in

1944/45 in the sixth piece of

his piano cycle Children's

Album op. 69. Opus 3, Theme

and Variations, is

dedicated to Nikolai Sokolov

(1859-1922), his teacher of

counterpoint, and ots eleven

variations were written the year

he died. Both works could have

been written by a minor

late-nineteenth-century Russian

composer. - It was only with the

E flat Scherzo op. 7 that

Shostakovich threw convention

out of the window. It is the

immediate precursor of his First

Symphony. The solo-status piano

gives tone colour and rhythm,

the bassoon struts and swaggers

in the trio, and the last word

is when the parts diverge

perilously. The main theme of

this Scherzo was re-used

by Shostakovich in his music to

the film The New Babylon

op. 18. (Rozhdestvensky

premiered this fascinating work

in 1981, together with the opus

26 film nusic, in a Leningrad

Philharmonic concert in the

orchestra's home city.)

The 1930 film Alone by

the two famous film directors

Georgy Kozintsev and Lev

Trauberg was half-way to being a

sound film. Although dialogue

was still shown as text on the

screen, the music was already

synchronized with the moving

pictures. As usual with

Kozintsev and Trauberg, the

story was a tragi-comic one: the

unsuccessful attempt by a

village schoolminstrress to

escape her straitened

circumstances. The music played

a part of its own, commenting on

the situations (master-stroke of

a bandstand orchestra,

barrel-organ nostalgia, wailing

of muted trumpets to elegiac

episodes). Instruments are

almost personified,

partecipating in the dialogue,

as in number 4 of the Suite

from the Film Alone op. 26

compiled by Rozhdestvensky.

The Big Lighting was

announced in 1932 as a comic

opera in progress at the Maly

Theatre in Leningrad, but

nothing came of it, because

Shostakovich could not get on

with the libretto.

Rozhdestvensky found the

manuscript score of the

unfinished work in the theatre

library in 1980; the libretto

itself had disappeared, but

probably treated a subject

popular at the time, namely the

experiences of a Soviet citizen

in a fictitious capitalist

country. Shostakovich had

already set a similar subject in

1930 in his ballet The

Golden Age, the journey of

a Soviet football team to the

West. The surviving fragments of

the opera describe the feverish

preparations for the Russian

guests at a hotel (2:1). The

architet prescribes an ambience

à la russe, with

appropriate commentaryfrom the

music. For instance, there are

quotations from Reinhold

Glière's then famous ballet Red

Poppy and the famous folk

song "A birch stood in the

field". The fast-moving American

way of life is illustrated by

the vigorous musical progress in

no. 4 (2:3), the factory owner

serenades his automobile like a

romantic hero of old singing the

praises of his beloved (2:4),

and the American worker

emotionally swears

American-Soviet friendship

(2:5). The opera fragments were

premiered in the Great Hall of

the Leningrad Philharmonic on

February 11, 1981.

The music to the short comic

film The Adventures of

Korzinkina op. 59 was

written in 1940 (and premiered

by Rozhdestvensky in Moscow in

1983). The eponymous heroine is

a station ticket clerk. She has

the warmest sympathy for the

plight of her train travellers

and does her best to help them,

as in the case of a singer

entered for a singing

competition who has fallen in

love with her. When the poor

fellow loses his voice at the

critical moment, she fights her

way onto the stage and insists

against all the rules on a

repeat performance, kissing him

in full view of the public,

whereupon he sings as if

divinely possessed. Shostakovich

drew on the music of the street

(2:9, March) and the

restaurant (2:11), refining and

redrawing it, adding the

fashionable instruments of the

day such as the saxophone and

the muted trumpet, and blending

in "inappropriate" instruments

like a tuba. Persecution

(2:10) is a parody of silent

film music, composed for two

pianos; the finale (2:13) is the

travesty of an apotheosis in

which soloists and choir

tenderly intone the heroine's

first name: Yanya. The closeness

to the word nyanya (nurse) is no

coincidence. Shostakovich, who

earned a living as a cinema

pianist in early life, is in his

element here.

The Suite No. 1 for Jazz

Orchestra was written in

1934 (a second followed four

years later). The premiere was

on March 24, 1934. It is a

curiosity, because the music is

dance music, not jazz,

embellished with witty episodes

and fashionable instruments.

The Romance "Spring, Spring"

op. 128 of 1967 is the last of

Shostakocivh's Pushkin settings

(preceded by Four Romances op.

46 and Four Monologues op. 91

from 1936 and 1952). The hopeful

strain of the opening is

misleading. The piece ends with

the prospect of "long dark

winter nights" in gloomy falling

unison chord patterns.

The music of the Golden

Mountains Suite op. 30a is

taken from the 1931 film of the

same name by Sergey Yutkevich.

The film is set in

pre-Revolutionary times. A

farmer's boy goes off to the

city to seek work and fortune. A

popular song of the day "If I

only had golden mountains" gives

expression to the lad's dreams,

providing a title to the film

and a man theme to the score.

The fanfares of the introduction

(2:18) suggest the departure of

an armed punishment squad. The

waltz (2:19) gained vast

popularity extending far beyond

the film and was transcribed for

brass bands and jazz groups; it

was to be heard on the street

and in cafes and restaurants,

and was arranged for piano by

the composer himself, to be

played as a rousing encore at

concert appearances. The fugue

(2:20) is a brilliant example of

special relationships between

image and sound: the screen

shows column after column of

workers marching up. Strikes

have been called in Baku and

Petrograd, accompanied by

summary executions. The mood is

captured by the funeral march

(2:21). In the finale (no. 6)

Shostakovich picked up the

closing bars of his Third May

Day Symphony (Pervomayskaya).

The suite was premiered in

Moscow in the autumn of 1931

under the baton of Alexander

Melik-Pshayev, at the same time

as the cinema premiere.

The music to Vladimir

Mayakovsky's The Bug (in

Russian "klop", also sometimes

translated as the flea)

was written for Vsevolod

Meyerhold's famous 1929

production. The piece and its

staging brillianty satirized

petty-bourgeois behaviour. The

music is satirical to match,

with its exaggerated four-square

marches, its tendency to lilting

waltz time, its descent into

polka step, and its singing saw

(flexatone) with its invariably

loud wailing tone.

Rozhdestvensky premiered the

Suite to The Bug op. 19

in Moscow in November 1982.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

J

& M Berridge)

|

|