|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 59057 2 - (c) 1998

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 14

for Soprano, Bass, String

Orchestra and Percussion, Op. 135 |

|

48' 40" |

|

| - 1. De Profundis (Federico

García-Lorca) |

4' 20" |

|

|

| -

2. Malaguena (Federico

García-Lorca) |

2' 48" |

|

|

| - 3. Loreley (Guillaume

Apollinaire) |

8' 49" |

|

|

| - 4. The Suicide (Guillaume

Apollinaire) |

6' 34" |

|

|

| - 5. On Watch (Guillaume

Apollinaire) |

3' 14" |

|

|

| - 6. Madam! Look (Guillaume

Apollinaire) |

1' 43" |

|

|

| - 7. In the Santé

(Guillaume Apollinaire) |

8' 49" |

|

|

| - 8. The

Zaporogian Cossack's Reply to the

Sultan of Constantinople (Guillaume

Apollinaire) |

2' 00" |

|

|

| - 9. O Delvig,

Delvig! (Wilhelm Küchelbecker) |

4' 31" |

|

|

| - 10. Death of the

Poet (Rainer Maria Rilke) |

4' 46" |

|

|

| - 11. Conclusion (Rainer

Maria Rilke) |

1' 07" |

|

|

6

Romances to Texts by Japanese

Poets, Op. 21 *

|

|

13' 06" |

|

| - 1. Love |

2' 56" |

|

|

| - 2. Before the

Suicide |

1' 43" |

|

|

| - 3. Immodest

Glance |

1' 07" |

|

|

| - 4. For the First

and the Last Time |

2' 56" |

|

|

| - 5. Hopeless Love |

2' 11" |

|

|

| - 6. The Death |

2' 15" |

|

|

| 4

Romances after Pushkin, Op. 46 |

|

12' 24" |

|

| - 1. Renaissance |

1' 53" |

|

|

| - 2. Jealous

Maiden |

1' 36" |

|

|

| - 3. Premonition |

3' 41" |

|

|

| - 4. Stances |

5' 14" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 |

|

43' 01" |

|

| - Allegretto |

7' 46"

|

|

|

| - Adagio - Largo -

Adagio - Largo |

16' 23"

|

|

|

- Allegretto

|

4' 33"

|

|

|

| - Adagio -

Allegretto - Adagio - Allegretto |

14' 20"

|

|

|

| 6

Romances to Texts by British

Poets, Op. 62a |

|

15' 09" |

|

| - 1. To a Song (Walter

Raieigh) |

3' 55" |

|

|

| - 2. In the Fields

(Robert Burns) |

3' 30" |

|

|

| - 3.

MacPherson before his

Execution (Robert

Burns)

|

2' 10" |

|

|

| - 4. Jenny (Robert

Burns) |

1' 45" |

|

|

| - 5. Sonnet No. 66

(William Shakespeare) |

3' 04" |

|

|

| - 6. The King's

Campaign (Trad. Children's

Song) |

0' 46" |

|

|

| 8

English and American Folk Songs |

|

16' 50" |

|

| - 1. The Sailor's

Bride (English) |

2' 58" |

|

|

| - 2. John

Andersson (English) |

2' 32" |

|

|

| - 3. Billy Boy (English) |

1' 32" |

|

|

| - 4. O, my Ash and

Oak (American) |

2' 55" |

|

|

| - 5. King Arthur's

Servants (English) |

0' 50" |

|

|

| - 6. Seems She

walked along the Rye (English) |

1' 58" |

|

|

| - 7. Spring Round

Dance (English) |

2' 00" |

|

|

| - 8. Jonny will

come Home again (American) |

2' 06" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

Makvala

Kasrashvili, soprano (Op.

135) |

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor |

Alexei

Maslennikov, tenor (Op.

21) |

|

|

Anatoly Saifulin,

bass (Opp. 135, 46 & 62a) |

|

|

Elena Ivanova,

soprano (8 English and American

Folk Songs: 11-17) |

|

|

Sergei Yakovenko,

baritone (8 English and American

Folk Songs: 18) |

|

|

Alexander Suptel,

violin (Op. 141) |

|

|

Irina Lozben,

flute (Op. 141) |

|

|

Vladimir

Pushkarev, trumpet (Op.

141) |

|

|

Sergei Minozhin,

cello (Op. 141) |

|

|

Valentin Savin,

doublebass (Op. 141) |

|

|

Rashid Galeyev,

trombone (Op. 141) |

|

|

Andrei Lysenko,

xilophone (Op. 141) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1982 (Op. 21)

- 1983 (Opp. 46 & 141)

- 1985 (Op. 135)

- 1986 (Op. 62a)

- 1989 (8 English and American

Folk Songs)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Igor

Veprintsev (Opp. 21, 46 &

62a), Severin Pazhukin (Opp. 135,

141 & 8 English and American

Folk Songs) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 59057

2 | 2 CD - 74' 31" - 75' 21" | (c)

1998 | (p) 1983, 1984, 1986, 1991

| DDD/ADD° |

|

|

Note |

|

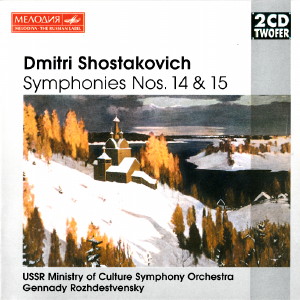

Front

cover: F. Vallotton, "Frozen canal

and bridge near the Heremitage of

St. Petersburg", 1913 |

|

|

|

|

"I

am dying because I

cannot live without

love"

The premiere of the 14th

Symphony op. 135 in 1969

caused a sensation in Moscow. A

generally taboo subject had been

made the subject pf public

deliberation: death. It was only

ten years later that

Rozhdestvensky ventured to

perform this outstanding work,

conducting it for the first time

in 1979 with the BBC

Symphony Orchestra in

Manchester.

Shostakovich himself had turned

to the phenomenon of death at an

early stage and devoted a number

of chamber-music works to the

subject since the Thirties. In

the 14th Symphony, however, he

made death the central theme in

the form of destructive force.

In 1968 the Prague Spring had

withered in the icy breath of

the Brezhnev doctrine. The 14th

Symphony is a cycle of eleven

songs (on texts by various poets

of different eras) for soprano

and baritone, small string

orchestra and percussion, in

which the music retains an

intimate dimension while

simultaneously capable of

expressive, eruptive outbursts.

The old second-interval

lamentation motif is

omnipresent, as is a theme

derived from the Dies irae

(the day of wrath in the

medieval requiem). This leads

into the symphony and introduces

the tenth movement, thereby

forming a circle. The eight song

takes the place of the

traditional scherzo: a dictator

is mocked (reply of the Zaporogian

Cossacks to the Sultan of

Constantinople by

Guillaume Apollinaire). The

scherzo is followed by the

lament, for banishment is the

poet's lot (O Delvig, Delvig!

by Wilhelm Küchelbecker).

Through the last two poems (by

Rainer Maria Rilke) the

phenomenon of death is elevated

to the level of a general

tragedy. The last words of the

symphony are: "Death is

great / We are his / With a

laughing mouth. / When we

think we're in the prime of

life / He dares to cry / In

our midst." European

civilisation is becoming an

ant-like activity, seeking to

avoid thoughts of death, and for

this reason this symphony has

earned a special status.

Shostakovich composed Six

Romances to texts by Japanese

poets Op. 21 for tenor and

orchester between 1928 and 1932.

They were not premiered until

April 24, 1966 in Leningrad and

Rozhdestvensky conducted them

for the first time in 1980 in

London. These romances are

dedicated to Nina Varsar, whom

Shostakovich passionately

pursued and married in 1932. For

the successful composer who

until then had only concentrated

on his work, love for this

beautiful and self-assured woman

brought Shostakovich his first

experience of how passion can

sometimes fail. The first three

texts are from an anthology of

Japanese lyric poetry published

in 1912 in St Petersburg which

Igor Stravinsky had used in

1912/13 for his Three

Japanese Songs. The tonal

space remains unspecified,

indeed vague, in this cycle,

with the vocal part

characterized by restrained

expressivity. This is no

light-hearted, rejoicing "Love"

(no. 1). Even the admission of

joy is articulated in a tragic

minor key. The second romance ("Before

the suicide") is of linear

stringency. Only the wild and

onomatopoeic imitated scream of

passing wild geese pulls

everything up short, since this

cry will survive beyond death.

The xylophone imagines "dark

dreams" and is to be found

frequently in this guise in

Shostakovich's works. There

follows an impressionistic

homage to the wind, allowing an

"Indiscret look" (no. 3)

at the girls' legs. This image

of light-hearted sensuality is

followed by the metaphors of

passionate union ("For the

first and last time", no.

4), while wan strings introduce

"Death" (no. 6). What

remains is a lonely, plaintive

voice: "I am dying because I

cannot live without love". This

dependence on the love of his

nearest and dearest, manifested

here for the first time in

textual and musical terms, was

to be a constant source of joy

and fear in Shostakovich's life;

it dominates his oeuvre in equal

measure with the fear of social

repression.

This is also subject of the Four

Romances after Pushkin op.

46, composed at the end of 1936.

Originally planned as a cycle of

six romances to mark the

centenary in 1937 of the

poet's death, the four romances

which were eventually finished

were only premiered in 1940,

since the cultural bureaucracy

had fatefully interfered

in Shostakovich's life in

1936 and banned some of his

works. The first romance takes

this conflict as its theme: Vozrozhdeniye

(rebirth). This is meant

literally (and not, as some

translations would have us

believe, as a representation of

the cultural Renaissance eraI.

Pushkin puts forward the thesis

that art barbarians may be able

to destroy a painting by a

genius, but that it remains in

the memory, to be recalled in

their minds, being as it were

spiritually reborn. Shostakovich

could identify fully with this

statement, since he had had to

withdraw the premiere of his

fourth symphony, a fact which

remained unforgotten in the

consciousness of the

music-loving public, so that the

work, "destroyed" by a Party

decree, was eventually able to

experience a triuphant rebirth

decades later. "Weeping

bitterly, the jealous girl

scolds the boy", is how

the second romance begins.

However, when the boy's head

sinks wearily onto the girl's

shoulder she smiles happily and

she cries only softly. The

lovers' tiff ends in

reconciliation, the painful

lamentation motif in seconds

giving way to a calming

stillness. "Black storm

clouds are again ahnging

threateningly above me"

(no. 3: Premonition). In the

battle between the artist and

the power of the state there is

only a temporary armistice,

according to Pushkin, and

similarly with Shostakovich.

Intervals of fourths build up

before memory of the loved one

brings release, brightness and

light. Readers will search in

vain for the title Stanzas in

Pushkin's brilliant verses of

the fourth romance because the

poem is unnamed: "Brozhu li

ya vdol' ulits shumnykh" (Whether

I wander through the noise of

the lanes). The poet was

thirty years old when he wrote

this poem in 1829 and

Shostakovich was the same age

when, in 19366, he set it to

music. This is no coincidence.

In both there is an expression

of existential experience of

transitoriness: of fame, art,

love. The last of the romances

is the best of this cycle from a

musical point of view; perhaps

it is even a key work in the

whole of Shostakovich's entire

oeuvre. Gennady Rozhdestvensky

orchestrated the songs which

were originally written for

piano accompaniment and

premiered his version in Moscow

in 1982.

The 15th Symphony op. 141,

Shostakovich's last, was

composed in 1971 and is a

masterpiece by a fatally sick

man. The first three movements

remind us of the turbulence of

life. The first movement,

described by Shostakovich as a

"toy shop" introduces a wealth

of fleet and commonplace topics

including the head motif of

Rossini's William Tell

overture, which is constantly

repeated. The fate motif from

Richard Wagner's The

Valkyrie, intertwined with

the "love, suffering and longing

motif" from Tristan und

Isolde dominates and

structures the last movement. In

the finale motives from the

composer's own early works are

quoted, especially from those

which had been regulated and

forbidden, such as the

percussion interlude from his

opera The Nose of 1928

and the notorius trombone

glissandi imitating sexual union

from the opera Lady Macbeth

of Mtsensk banned in 1936.

The close proximity of innocuous

gaiety and deathly seriousness

shocked the audience at the 1972

premiere in Moscow. Gennady

Roshdestvensky conducted the

symphony in the same year; both

then and later he did not soften

the musical allusions,

preferring to give them pride of

place. This lends presence and

emphasis to the banal figures of

the first movements, crowing

with the Rossini quote, while

giving weight to all the sounds

which are the harbingers of the

sombre fate motif from the

Valkyries. "Only the doomed

deserve my gaze: ho who looks

upon me takes leave of the

light of life", is

Wagner's parallel passage.

Unlike the great old master of

Russian conducting, Mravinsky,

Rozhdestvensky does not develop

the coda, with its pedal point

in the strings, into a "musica

angelica". Bells, xylophone and

celesta conjure up a soft, yet

relentless time-count: the

ticking of an expiring clock.

The Six Romances to texts by

Raleigh, Burns and Shakespeare,

op. 62 were written in 1942 in

Kuybyshev (now Samara), to where

Shostakovich had been evacuated

during the Leningrad blockade.

The first three romances were

actually premiered in Kuybyshev,

with Shostakovich himself at the

piano, on November 4, 1942,

while the entire cycle was first

premiered on June 6, 1943 in the

Small Hall of the Moscow

Conservatory (again with the

composer at the keyboard).

Shostakovich completed a version

for large orchestra (op. 62a) in

1943 which was however never

played in his lifetime and which

is to be heard on the present

recording. The chamber-orchestra

version (op. 140) composed in

1971 was premiered in Moscow on

November 30, 1973. In Samuil

Marshak and Boris Pasternak,

Shostakovich had found the best

possible translators of the

English texts. The romance To

the Son (2:5, Walter

Raleigh) warns of allowing three

things to unite: wood, a rope

and a scoundrel. Perhaps the son

himself was the scoundrel,

hanged on the gallows for

"higher ends". To denounce

someone as a scoundrel was

certainly a common practice both

in Elizabethan England and in

the Societ era, and remains so

to this day the world over.

Shostakovich dedicated the

romance to his friend, the

composer Lev Atovmyan

(1901-1973). In Robert Burns' On

Snowcovered fields (2:6)

one person assures another that

he will support him no matter

what the weather, in snow, wind

or rain, persecution or any

other need. The composer

dedicated this romance to his

first wife Mina (who died in

1954). MacPherson's farewell

(2:7, Robert Burns) is an

ironical paraphrase about death.

MacPherson, never one to miss a

battle, goes willingly to his

execution. Shostakovich had this

to say about the topic: "The

poet Shoshchenko said that if

someone writes ironically about

death, then he loses his fear of

it. For a while I agreed with

Shoshchenko, I even wrote a

romance about it called

MacPherson before his execution

(...). But later I realized that

even Shoshchenko could not

liberate himself from the fear

of death. (...) And so my

attitude to this problem

changed." The romance is

dedicated to Isaak Glikmann. Jenny

(2:8, Burns) is an ironic tale

of a courtship and dedicated to

Shostakovich's friend and

fellow-composer Yuri (Georgy)

Sviridov (1915-1998). The focal

point of the cycle is the fifth

romance (2:9), the setting of

William Shakespeare's 66th

Sonnet, dedicated to the

brilliant aesthetician and

friend of Shostakovich, Ivan

Sollertinsky (1902-1944).

Sustained chords in the strings

and the sound of bells conjure

up the dull passing of time:

"Tir'd with all these, for

restful death I cry ... And

needy nothing trimm'd in

jollity, And gilded honour

shamefully misplac'd, (...) And

art made tonguetied by

authority, And folly -

doctor-like - controlling skill,

(...) Tir'd with all these, from

these would I be gone, Save

that, to die, I leave my love

alone." The finale (2:10) is

provided by the English

children's song Royal

Procession: "The King of

France went up the hill with

twenty thousand men, / The King

of France came down the hill and

never went up again." (Marshak:

Po sklonu vverkh korol' povel

polki svoikh strelkov. Po sklonu

vniz korol' soshol, no tol'ko

bez polkov.) Shostakovich

dresses the biting wit in a

sharp allegretto tempo and polka

mode. This time the dedicatee is

another fellow-composer,

Vissaryon Shebalin (1902-1963).

Rozhdestvensky conducted the

cycle for the first time in 1978

in Austria.

The Setting of Eight English

and American Folk Songs

was probably written in 1944.

Ever since the premiere in 1942

of his colossal anti-war

symphony, the seventh,

Shostakovich had become the most

popular of all Russian composers

abroad. After the work's

American premiere in July 1942

under Arturo Toscanini there

were a further 60 performances

on the American continent (in

the USA, Canada, Mexico,

Argentina, Uruguay and Peru) and

this was the reason why

Shostakovich turned to arranging

folk songs, as a way of

expressing the fraternal unity

of all peoples.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

J

& M Berridge)

|

|