|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 53547 2 - (c) 1998

|

|

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

Symphony No. 7 in

C Major, Op. 60 "Leningrad"

|

|

75' 00" |

|

| - Allegretto |

27' 37" |

|

|

| -

Moderato (poco Allegretto) |

10' 59" |

|

|

| - Adagio |

15' 52" |

|

|

| - Allegro non

troppo |

20' 32" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 65 |

|

62' 44" |

|

| - Adagio |

24' 57"

|

|

|

| - Allegretto |

6' 39"

|

|

|

- Allegro non

troppo

|

6' 48"

|

|

|

- Largo

|

10' 28"

|

|

|

| - Allegretto |

13' 52" |

|

|

| Songs

for Shakespear's "King Lear", Op.

58a |

|

12' 33" |

|

| Introduction and

Cordelia's ballad |

3' 56" |

|

|

| Ten Buffon's Songs

(Adaption by Samuil Marshak): |

|

|

|

| - 1. Who has

decided to divide his kingdom

piece by piece may join the

fools... |

0' 24" |

|

|

- 2. It's a sad

day for fools: All the bright

people in the country have lost

their wits and become the likes of

me...

|

0' 52" |

|

|

- 3. Breadseeds

and breadcrusts is what the hungry

little mouse remembers in the

hole...

|

0' 19" |

|

|

| - 4. The sparrow

reared the cuckoo, the homeless

baby bird... |

0' 46" |

|

|

| - 5. High-ranking

and rich fathers are treated

nicely by daughters and

sons-in-law. |

0' 40" |

|

|

| - 6. When the

priest refuses to sell his soul

for the sake of money... |

1' 09" |

|

|

| - 7. The cunning

fox and the king's daughter,

your's would be the rope... |

0' 49" |

|

|

| - 8. The trousers

are necessary, I assure you... |

0' 49" |

|

|

| - 9. Hey! Hi

there! Who keeps his temper when

an ill wind blows: thunder,

lighting and hail... |

0' 54" |

|

|

| - 10. Who is a

soldier of fortune... |

1' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry of

Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

Sergei Grishin,

English horn (Op. 65, mvt. 1) |

|

| Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, conductor |

Natalia

Burnasheva, soprano (Op.

58a, Introduction) |

|

|

Evgeni Nesterenko,

bass (Op. 58a, Ten Buffon's

Songs: 1-10) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1984 (Opp. 60 & 58a)

- 1983 (Op. 65) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Igor

Veprintsev (Opp. 60 & 58a),

Severin Pazhukin (Op. 65) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 53457

2 | 2 CD - 75' 00" - 75' 36" | (c)

1998 | (p) 1984, 1986, 1987 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

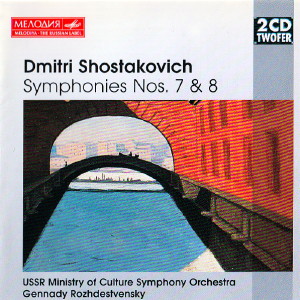

Front

cover: F. Vallotton, "Frozen canal

and bridge near the Heremitage of

St. Petersburg", 1913 |

|

|

|

|

"Music...

it's able to express

everything without a

single word!"

Hardly any other symphony of

the 20th century has become as

popular and yet remained as

unknown, in spite of its

apparent unambiguity, as the Leningrad

Symphony by Dmitry

Shostakovich (1906-1975).

Gennady Rozhdestvensky has only

added it quite late to his

repertoire. The first time he

cunducted Shostakovich was in

1952 (First Symphony). Then,

after the sensational success of

the 9th Symphony with the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra in 1958,

he swiftly included further

symphonies into his repertoire.

Yet it was as late as 1967 that

he first conducted the Leningrad

Symphony, actually at a

concert with the USSR RTV Large

Symphony Orchestra at the

Tchaikovsky Conservatory in

Moscow. By then he had good

reasons to assume, that the

Seventh Symphony would not only

be seens as an anti-war

symphony, but understood to have

a deeper underlying meaning that

finally could be conveyed and

perceived.

The Seventh Symphony has become

a symbol of monumantal war and

funeral music. This is certainly

due to the circumstances of its

genesis and circulation. Though

Shostakovich had started to

compose it in the summer of

1941, while Leningrad was

besieged by German fascist

troops, it had its première on 5

March 1942 in the remote

Kuybyshev (today renamed into

Samara), to which a lot of

artists had been evacuated. Its

music seemed to symbolise the

heroic determination to fight

and survive. As such it was not

only perceived and

enthusiastically celebrated in

the Soviet Union but also

throughout Western Europe.

Conductors such as Arturo

Toscanini, Artur Rodzinski, and

Dmitry Mitropoulus counted it an

honour to perform it. It was in

keeping with the spirit of the

time. The composer himself

honoured it, on the occasion of

the première, by publishing some

programmatic annotations in the

Pravda. Only when

Shostakovich's reputation as a

completely loyal composer was

demystified through Solomon

Volkov's book Svidetelstvo

(testimony), a new

interpretation of this symphony

became possible. This was not

only true for the Soviet union,

but also for the Western World

and had become necessary,

because the Soviet Union had

transformed from a war victim

into an aggressor in the

meantime. Shostakovich has

dedicated his work to Leningrad.

But this city, as Alexander

Solzhenitsyn has pointed out in

his book The Gulag

Archipelago, has served to

populate the "Kolyma", the

Stalinist extermination camp in

the 1930s. Solzhenitsyn reduced

it to the following formula:

"Leningrad was deported from

Leningrad", in fact by its own

people and in peacetime! Neither

does the writer blame the

horrendous number of death on

Hitler alone, but also on those

"who raked in their salaries for

a decade and knew of Leningrad's

exposed position", but did not

do anything to protect the city.

Soviet bureaucracy and Hitler

resulted in the disaster of the

blockade of Leningrad.

Shostakovich's ymphony bears

witness to this gruesome pact

between normal everyday

indolence and extraordinary

criminals, especially in the

first and last movement. Their

unusual quality does not lie so

much in clearly relating and

confronting song-like themes

about patriotism and the love of

peace with march-like themes of

the enemy and the threat they

constitute. Rather their most

outstanding characteristic is

the general ambiguity of all

themes and motifs as well as the

musical emancipation of

triviality. Rozhdestvensky

brings out the details

succinctly and bitingly. In

musical leterature, the

succession of variations in the

first movement, a monotonous

"march motif", which repeats

itself eleven times, has been

erroneously interpreted as "a

theme about the invasion of the

enemies". After its first

appearance this theme is

delicately stippled by the

violins and violas playing

pizzicato and pianissimo. Then

it develops progressively into a

somewhat "indecent chanson"

accompanied by roaring

trombones. In the background

Rozhdestvensky creates the

impression of dancing skeletons:

with the rattling noise of

violin chords beaten by the bow

stick. An impressive fortissimo

opposes the absolute stupidity

of the trivial evil to gestures

of protest. The recapitulation

begins with an Adagio (solo

bassoon) in the style of a

requiem. In the fourth movement,

the separated spheres of public

and private life merge: a

jubilation machinery begins to

work, soon interrupted by

passages of funeral music. Here

we find an allegory of one of

the fundamental experiences of

this century; the simultanelty

of state ordered optimism and

individual grief. The two

central movements don't present

a contrasting idyllic scenery.

In the second movement the music

seems to hold its breath, fear

is presented as a fundamental

form of existence. The third

movement is based on the sharp

tension between "funebre" and

"doloroso". It is dominated by

the deep register, by sonorities

based on fourths and fifths.

Everything here expresses

repressed feelings, until string

cantilenas permit the grief

articulate itself. Especially

Rozhdestvensky's interpretations

of the outer movements are

noteworthy. He has discovered

the Seventh Symphony for his

generation, for those who grew

up with the lies of the former

generation. For this reason he

allows for the turmoils of

survival in a pining and

agony-stricken society.

With the same orchestra as

before, Rozhdestvensky conducted

the Eighth Symphony for the

first time in Moscow in 1965.

The symphony had had its Moscow

première on 4 November 1943, in

honour of the Soviet government

and under the impression that

the battle of Stalingrad

signified the turn of the war.

Since the international success

of his Seventh Symphony,

Shostakovich had advanced to the

most famous Soviet composer, not

to mention the most lucrative

one. The CBS, for example, has

paid 10,000 dollars to the

Soviet Union for the performing

rights of the Eighth Symphony.

The opinion about the Moscow

première was divided. People had

expected a heroic and patriotic

symphony by Shostakovich.

Instead they heard a first

movement which lasted nearly

half an hour, with a disturbing

lamentation, followed by two

strange masquerade.like

movements and a Largo using the

old passacaglia form. The work

ended with a fifth movement

containing a finale "senza

animando" and "morendo". One

heard a poem of grief. In a

creative retrospect from 1946

the composer said: "I wanted to

depict the emotional state of

someone who has been stunned by

the hammer of war. This person

has to face agonising trials and

catastrophes. His path is

neither a bed of roses nor

accompanied by cheerful

drummers..." Of course such a

programme wasn't to the taste of

the official Moscow of 1943.

Thus the absurd attempt was made

to give the symphony the epithet

"Stalingrad". But even then

there were people who understood

Shostakovich's message, like the

writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who wrote

the following about the première

of the Eighth Symphony: "...all

of a sudden the voice of the

antique chorus of Greek tragedy

resounded. Music is so much at

the advantage, it can express

everything without uttering a

single word." Evgeny Mravinsky,

whom the 8th Symphony was

dedicated to, and who conducted

its première, had already

interpreted the third movement

as parable of blind raging fate.

Rozhdestvensky followed his

example in this respect. He,

too, created an oppressive study

about the impotence of the

individual, one of the other

basic experience of the 20th

century. In monotonous

industriousness a "voice" plods

and stumbles around all by

itself, as if ordered about by

chordal whip-lashes and shrill

entries of the winds. One voice

turns into many, victoriously a

trumpet triumphs. After writhing

with pain the lamentation of the

Largo resounds: twelve

variations of a nine-bar bass

theme. Rozhdestvensky turns them

into a study about the

mercilessness of time. Maybe one

of the most impressive sections

is the "standstill of time", the

total disintegration of form at

the end of the symphony, a

disturbing act, which has an

existential as well as a social

meaning: dying, end of time,

devastation.

The songs for Sjakespeare's King

Lear were written for a

performance at the Grand

Dramatic Theatre of Leningrad

(director: Georgi Kozinstsev) in

1940. During the Stalin era a

production of Shakespeare was by

no means a matter of course. The

composer reports: "Everybody

knows that our best Lear was

Mikhoëls from the Yiddish

Theatre. And, everybody knows

how he died, a dreadful end. And

what happened to Pasternak, our

best Shakespeare translator?

These names symbolise tragedies,

which are more tragic than

anything tragic in Shakespeare's

pieces. No, its much better to

have nothing to do with

Shakespeare. Only very careless

people get involved in such a

suicide mission. This

Shakespeare is highly

explosive." Salomon Mikhoëls

(1890-1948), actor and founder

of the Yiddish Theatre in

Moscow, was killed on orders of

the party, the deed disguised as

an act of criminals. The Yiddish

Theatre was closed in 1949.

Between 1936 and 1943 Boris

Pasternak (1890-1960) was hardly

published in Russia and had to

earn his living doing

translations. The fact that

Rozhdestvensky was able to

record Shostakovich's Lear-music

in Moscow in 1984 was only

possible due to Evgeni

Nesterenko's help. Born in 1938,

this bass singer is one of the

most distinguished interpreters

of Russian classical art. apart

from that, he has indomitably

supported Shostakovich's works.

Amongst others, he was the first

to perform the vocal part of the

politically loaded Michelangelo

suite and the Four Poems of

Captain Lebedyakin.

Furthermore, he included the Ten

Buffon's Songs into his

concert repertoire. But although

their texts are from

Shakespeare's Lear, the poet

Samuil Marshak (1887-1964) has

modified them so strongly

according to Russian sentiment,

that one has to consider them

more or less as free

adaptations. Shostakovich

completely restrains himself and

his music is accentuated on ly

by scarce means. Cordelia's

ballad introduces the

composition like a motto. It

describes an empty house, which

had been inhabited once.

Buffeted by Thunder, while

haunted by Merlin, the magician,

it remains silent and empty.

This corresponded with the

situation of many families

during the great waves of

deportation. Shostakovich has

accompanied the ballad with a

low sustaining rhythm,

resembling ghosts riding through

the night. This musical motif

signals threat and hope at the

same time. It is also present in

the fool's songs. The sequence

of the songs follows a

well-considered dramaturgy. Over

and over again the factual case

Lear becomes the object of

ridicule (1, 5, 7, 8). People

lament that wise men become

fools, thereby putting fools out

of work (2). Incidents from the

animal kingdom serve to

illustrate human nature (3, 4).

The fool's prophecy (Lear: III,

3) and his résumé about

friendship and foolishness (II,

4) summarises the tragedy and

constitutes its climax. Stalin's

apprehensions concerning

Shakespeare were well founded,

for the prophecy says: If the

judges would punish those, who

are really guilty for a change,

the state would get out of

joint, but one would be able to

hold up one's head at last.

Shostakovich saw himself as

"yurodivi", as holy simpleton,

who was traditionally entitled

to speak the truth in Russia.

The composer used this right in

his songs.

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

A.

Hofmann)

|

|