|

|

2 CDs

- 74321 49611 2 - (c) 1997

|

|

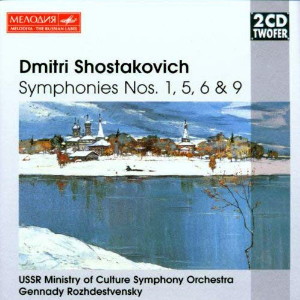

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compact Disc 1 |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 1 in

F Minor, Op. 10 |

|

33' 27" |

|

| - Allegretto -

Allegro non troppo |

8' 42" |

|

|

| -

Allegro |

4' 31" |

|

|

| - Lento |

10' 23" |

|

|

- Allegro molto

|

9' 51" |

|

|

| Symphony No. 6 in

B Minor, Op. 54 |

|

31' 11" |

|

| - Largo |

17' 11" |

|

|

| - Allegro |

6' 39" |

|

|

| - Presto |

7' 20" |

|

|

| Compact Disc 2 |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47 |

|

46' 44" |

|

- Moderato -

Allegro non troppo - Moderato

|

15' 21"

|

|

|

| - Allegretto |

5' 24"

|

|

|

| - Allegro |

14' 11"

|

|

|

- Allegro non troppo

|

11' 03"

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 9 in E flat Major, Op. 70 |

|

26' 39" |

|

| - Allegro |

5' 16" |

|

|

| - Moderato |

7' 37" |

|

|

| - Presto |

3' 01" |

|

|

| - Largo |

4' 05" |

|

|

| - Allegretto |

6' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USSR Ministry

of Culture Symphony Orchestra

|

|

| Gennady Rozhdestvensky,

conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Moscow:

- 1984 (Opp. 10 & 47)

- 1983 (Opp. 54 & 70) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

S.

Pazhukin (Opp. 10 & 70), E.

Shakhnazaryan (Op. 54), I.

Veprintsev & E. Buneyeva (Op.

47) |

|

|

Prime Edizioni

LP |

|

Melodiya |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

BMG

Classics "2 CD Twofer" 74231 49611

2 | 2 CD - 64' 47" - 72' 46" | (c)

1997 | (p) 1983-1985 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Front

cover: Ilya Glazunov, "The first

snow", 1968 |

|

|

|

|

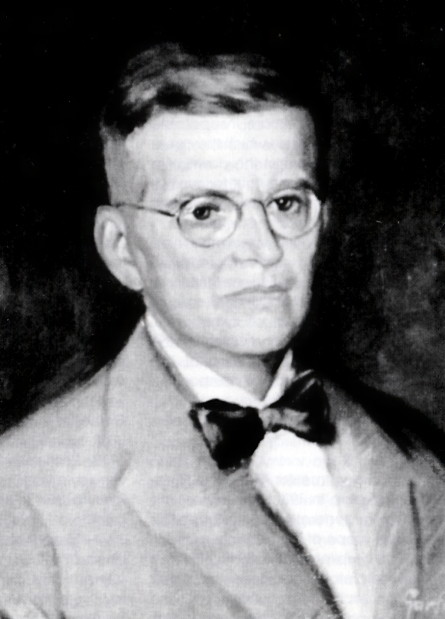

A

conductor of unusual

calibre A

conductor of unusual

calibre

The symphonies of Dmitri

Shostakovich (1906-1975) are

among the classics of the

twentieth century. They are

inseparable from the

circumstances in which they were

composed: enthusiasm at the dawn

of a new era and the ensuing

fight for survival under a cruel

regime. Yet this is not their

message. Each generation has

placed its own interpretation on

these symphonies, the composer's

own contemporaries included.

Conductors like Evgeny Mravinsky

(1903-1988), who conducted the

premieres of most of the

Shostakovich symphonies,

belonged to the generation which

felt the utter powerlessness of

the individual. This led to a

kind of interpretative

"composure", which put details

into sharp, and sometimes

over-precise, docus, to

relentlessness and objectivity.

The opposite is true for Gennady

Rozhdestvensky, born in 1931,

and thus of the succeeding

generation. He placed his faith

in the scope of the subject, and

realized it too, despite many

setbacks. For this reason,

interpretative composure is not

part of his approach, but rather

a surcharged emotionality and

hot-headed, exaggerated clarity,

particularly in the emphasis he

places on black humour and

irony.

While Shostakovich was still

alive, Gennady Rozhdestvensky

performed the miracle of staging

the composer's officially

ostracized first opera The

Nose in Moscow for the

first time in 1974 - forty-four

years after its premiere! The

composer was to reward him well

and lovingly. Following

Shostakovich's death,

Rozhdestvensky concerned himself

with the early works - not

exactly popular with the

authorities - and, using the

composer's manuscripts to

reconstruct the opera The

Gambleers as well as

various pieces of film music,

made them available on a series

of recordings entitled "From the

manuscripts of the early years".

At the same time, he began

working on the largescale

project of recording all the

Shostakovich symphonies with

"his" orchestra, the Orchestra

of the Ministry for Culture of

the USSR, which had been created

for him in 1982. Rozhdestvensky

was at that time already much in

demand as a conductor outside

the Soviet Union (principal

conductor of the Stockholm

Philharmonic, 1974-77, and of

the BBC Symphony Orchestra,

1978-81), and he exploited his

international acclaim by giving

public exposure to the full

breadth and significance of

Shostakovich's work.

His very first international

presentation, of the Symphony

no. 1 in F minor op. 10

with the Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra of London in 1958, was

a sensation. At the time

Rozhdestvensky was 27 years of

age and deputy conductor at the

Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow.

Dmitri Shostakovich had composed

his first symphony as his final

examination piece for the

Conservatoire in 1926, when he

was nineteen. Performed for the

first time by Nikolai Malko and

the Leningrad Philharmonic in

1926, the work was received with

acclaim and was to form the

basis of his reputation as a

composer. Bruno Walter conducted

the work in Berlin in 1926 and

in Vienna and Mannheim in 1930,

while its American premiere took

place under the baton of Leopold

Stokowski in 1928.

This symphony already contains

all the elements which would

characterize the later works:

audacious instrumental subjects,

most particularly the inclusion

of the solo piano (movements 2

and 4), the everpresent

potential for tragic tone in the

tentative melodic developments,

violently explosive scherzo

grotesques that speak of hurt at

the way of the world (second

movement), the sound of the

streets, including march-like

intonations, waltz fragments,

laments. The third movement

(Lento), for example, is based

upon the harmonic and rhythmic

ideogram of the old lament

"Immortal victims". Sublimity

derives from the banal and

trivial, and vice versa. There

is no "unity of mood". Instead,

opposing and generally mutually

exclusive areas of expression

are linked and confronted.

Traditional elements are

incorporated with supreme

mastery. In the final movement,

dark runs in the strings and

chromatic passages create a

"Götterdammerung" mood as in

Richard Wagner and, in the style

of Gustav Mahler, a "cheerful"

execution i straged to drums and

brass. Instead of defining and

presenting these elements under

the guise of "educating the

masses" (as is the case in many

performances), Rozhdestvensky

fuses them in all their

disparity into a compelling

commentary on the state of the

world. A masterpiece in a

masterly interpretation.

Composed in April/May 1937, the

Symphony no. 5 in D minor,

op. 47 assumed the significance

of "fateful symphony" for

Shostakovich. He wrote it at the

time of the worst of Stalin's

"purges", of mass execution and

deportation. The composer had

every reason to fear being

deported. Friends of his, such

as the marshal of the Red Army,

Mikhail Tukhachevsky

(1893-1937), were being shot

under martial law. Shostakovich

himself had fallen out of

Stalin's favour with his opera Lady

Macbeth of Mtsensk at the

beginning of 1936. His works

were deleted from concert

programmes overnight, and he

himself had been declared an

"enemy of the people". He was

given the chance in 1937 to

"rehabilitate" himself with a

new work. Today we know that

this redemption was the result

of Maxim Gorky's personal

written plea to Stalin.

Uncompromising in the music of

his fifth symphony, in the

run-up to its first performance

Shostakovich had nevertheless

verbally declared his adherence

to Socialist Realism and had

given his symphony an

appropriate label: "The growth

of a personality". This token of

allegiance was accepted by the

Societ rulers, yet to sensitive

listeners at the premiere the

discrepancy between word and

worl was apparent. Their

demonstrative applause was for

the codead message. In the

opinion of the Shostakovich

biographer, Solomon Volkov, "an

upright, thinking person is

represented here, who, under

tremendous moral pressure, has

to make a crucial decision.

Neurotic pulse beats run through

the whole symphony, the composer

searching feverishly for a way

out of the labyrinth, only to

find himself, in the finale

(...), in the 'gas chamber of

thoughts' once more".

This symphony is one of the most

popular, and at the same time

one of the most misunderstood of

Shostakovich's works. The

difficulty lies in making its

tragic elements understandable

to people living in

circumstances which are socially

and biographically far from the

tragic. Rozhdestvensky

exaggerates with denunciatory

delight and raging fury the

noisy, idle activism of the

bureaucrats of then and now, and

has the monologues of the solo

instruments sound like intimate

confessions, thereby creating

the necessary musical urgency:

"Everyone should be clear about

what happens in the Fifth. The

jubilation is produced under

duress, as if someone were to

beat us whit a cudgel and at the

same time say 'you should

rejoice, you shoud rejoice'. And

the maltreated person rises,

though his legs can barely hold

him, and marches round murmuring

'we should rejoice, we should

rejoice'." (Shostakovich)

With his Fifth Symphony

Shostakovich succeeded in

placing artistic conformity

against resistance in a kind of

balancing act. He had escaped

the agonies of concentration

camp life and death, but the

inner desperation, the hell of

fear, still remained to be

overcome. This took place in the

Symphony no. 6 in B minor

op. 54, composed between April

and October 1939 and premiered

by Evgeny Mravinsky with the

Leningrad Philharmonic in the

same year. Shostakovich had

carefully prepared the way for

the event by denying any hint of

an "inner" programme and letting

it be known that he was planning

a work dedicated to Lenin. The

reactions at the first

performance on November 5, 1939

were thus understandable. The

official press was disappointed

and confused.

The three-movement symphony

begins, in contravention of the

rule, not with an Allegro but

with a Largo expressing sorrow

over the people who disappeared

in Stalin's camps, murdered in

the name of "a better future".

External expressive devices are

lacking; instead, an internal

harmonic tension prevails and

the music gradually fades out.

Both the number of instruments

and the volume at which they are

to play are progressively

reduced. The second and third

movements contrast most strongly

with this. Here the way of the

world is represented by evil

laughter and lively figure work.

The coda realizes what the close

of the fifth symphony had only

suggested: concentrated

supernatural materialization.

"The thought of waiting to be

executed is something that has

tortured me throughout my life.

Many pages of my music speak of

it," confessed Shostakovich. So

too with the Sixth Symphony.

Trascending the special

circumstances of its conception,

it presents a musical picture of

man's fear of death generally

and of rebellion. Roshdestvensky

lays the interpretative emphasis

on the striking depiction of the

forced clowning of life.

The Symphony no. 9 in E

flat major op. 70 was

composed immediately after the

end of the war, during

July/August 1945. A victory

symphony was expected of

Shostakovich. The first

performance on November 3, 1945,

was therefore a fiasco, since

the composer had departed from

the Beethoven model of a

powerful Ninth and, far worse,

had omitted to pay homage to the

"Leader of the people", its

"dear father" Stalin.

Instead, the Ninth Symphony

contains a charming musical

examination of the century's

"stride of uniformity" - the

march. The march appears as the

symbol of conformism,

"conformism as the mortal sin of

modern man" (Hannah Arendt).

Grotesques suddenly change into

military marches, which in turn

become circus music and

scherzando episodes.

Gifted with wit, humour and

irony, Rozhdestvensky is

absolutely in his element here.

In November 1982, in one of his

now legendary series of concerts

in Moscow presenting modern

Russian composers, he declared

the ninth Symphony to be one of

the most important works in all

Russian music: "Written at a

difficult time, directly after

the end of the war, its

cheerfulness and shrewdness are

in many ways reminiscent of

Haydn and Mozart. But the wounds

which the war had caused were

not yet healed, they still hurt,

and we hear the screams of pain

- in the fourth movement of the

symphony, in the urgent bassoon

monologue."

Sigrid

Neef

(Transl.:

J & M Berridge)

|

|