|

|

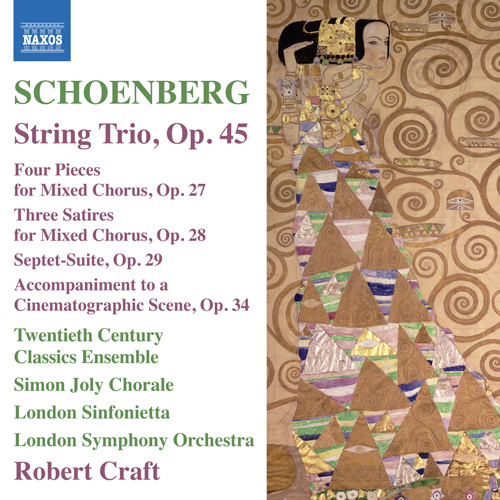

1 CD -

8-557529 - (c) 2010

|

|

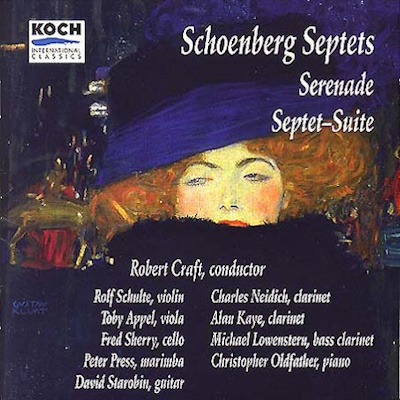

1 CD -

3-7334-2 - (p) 1997 *

|

|

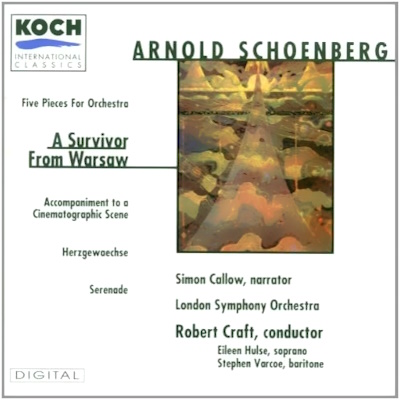

| 1 CD -

3-7263-2 - (p) 1995 ** |

|

| THE ROBERT

CRAFT COLLECTION - The Music of Arnold

Schoenberg - Volume 11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arnold

SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) |

String

Trio, Op. 45 (1946)

|

|

|

18' 53"

|

|

|

-

Part 1

|

|

1' 58" |

|

1 |

|

-

1st Episode

|

|

5' 28" |

|

2 |

|

-

Part 2 |

|

3' 22" |

|

3 |

|

-

2st Episode |

|

2' 45" |

|

4 |

|

-

Part 3 |

|

5' 20" |

|

5 |

|

Four

Pieces for Mixed Churus, Op. 27

(1925) |

|

|

11' 01" |

|

|

-

No. 1 Unentrinnbar

|

|

1' 39" |

|

6 |

|

-

No. 2 Du sollst nicht, du musst |

|

1' 19" |

|

7 |

|

-

No. 3 Mond und Menschen |

|

3' 33" |

|

8 |

|

-

No. 4 Der Wunsch des Liebhabers

|

|

4' 30" |

|

9 |

|

Three

Satires for Mixed Chorus, Op. 28

(1925-26)

|

|

|

11' 28" |

|

|

-

No. 1 Am Scheideweg

|

|

1' 08" |

|

10 |

|

-

No. 2 Vielseitigkeit

|

|

0' 39" |

|

11 |

|

-

No. 3 Der neue Klassizismus

|

|

9' 41" |

|

12 |

|

Septet-Suite,

Op. 29 (1925-26) |

*

|

|

29' 12" |

|

|

-

1. Ouverture. Allegretto

|

|

8' 38" |

|

13 |

|

-

2. Tanzschritte. Moderato

|

|

7' 41" |

|

14 |

|

-

3. Thema mit Variationen

|

|

5' 46" |

|

15 |

|

-

4. Gigue

|

|

7' 07" |

|

16 |

|

Accompaniment

to a Cinematographic Scene, Op. 34

(Threatening Danger, Fear,

Catastrophe) (1929-30)

|

** |

|

8' 38" |

17 |

|

|

|

|

String Trio,

Op. 45

Rolf

Schulte, Violin

Richard O'Neill, Viola

Fred

Sherry, Cello

|

Four Pieces for

Mixed Churus, Op. 27

SIMON JOLY

CHORALE

Members of the

LONDON SINFONIETTA

- Mark van de Wiel, Clarinet

- Alison Stephens, Mandolin

- David Alberman, Violin

- Timothy Gill, Cello

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

Three Satires,

Op. 28

SIMON JOLY

CHORALE

Members

of the

LONDON SINFONIETTA

- Paul

Silverthorne, Viola

- Timothy Gill, Cello

- John Constable, Piano

Robertrt CRAFT,

conductor |

Septet-Suite,

Op. 29

Christopher

Oldfather, Piano

Charles

Neidich, Clarinet

Alan R. Kay,

Clarinet

Michael Lowenstern,

Bass clarinet

Rolf Schulte, Violin

Toby Appel, Viola

Fred Sherry, Cello

|

Cinematographic

Scene, Op. 34

LONDON SYMPHONY

ORCHESTRA

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

American

Academy of Arts and Letters, New

York (USA) - 20 November 2005 (Op.

45)

Abbey Road Studio One, London

(England):

- 9 June 2006 (Opp, 27, 28)

- 28/29 May 1994 (Op. 34)

Master Sound Astoria Studios,

Astoria, New York (USA) - February

1995 (Op. 29)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Philip Traugott

(Opp. 45, 27, 28)

Michael Fine (Opp. 29, 34)

|

|

|

Editing |

|

Tim

Martyn (Op. 45)

Raphaël Mouterde (Opp. 27, 28)

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Tim

Martyn (Op. 45)

Mike Hatch (Opp. 27, 28)

Ben Rizzi (Op. 29)

Simon Rhodes (Op. 34)

|

|

|

NAXOS Edition |

|

Naxos

- 8.557529 | (1 CD) | LC 05537 |

durata 79' 12" | (c) 2010 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH previously

released |

|

KOCH

International Classics | 3-7334-2

| (1 Cd) | LC 06644 | (p) 1997 |

DDD | (Op. 29)

KOCH

International Classics | 3-7263-2

| (1 Cd) | LC 06644 | (p) 1995 |

DDD | (Op. 34)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Expectation

by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918)

(MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied

Arts), Vienna, Austria / The

Bridgeman Art Library)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Naxos’s Robert Craft

Collection has been acclaimed as

‘one of the most enticing

Schoenberg collections around’ (MusicWeb

on 8.557523), with Fanfare

proclaiming that ‘Craft outshines

them all’ (8.557526), to mention

only two critical commendations.

He has twice won the Grand Prix du

Disque, as well as the Edison

Prize for his landmark recordings

of Schoenberg, Webern and Varèse,

and countless other awards.

Craft’s consummate artistry and

unique insight continue to bear

fruit with this volume featuring

diverse works spanning more than

twenty years of Schoenberg’s

controversial and highly

influential career.

String Trio, Op. 45

In a burst of creativity following

a near fatal collapse on 2 August

1946, Arnold Schoenberg composed

three important works in a row, String

Trio, A Survivor from

Warsaw, and Phantasy.

Although the Trio was written

after the collapse, the commission

from A. Tillman Merrit of Harvard

University came earlier;

Schoenberg had already begun plans

for the piece in June 1946.

Musicians and audiences have

speculated about the

“autobiographical” nature of this

composition, but it is good to

know what Arnold Schoenberg wrote,

in 1949, about what he jokingly

called “my fatality”:

I awoke with a

terrible pain in my chest. I

sprang from the bed and sat

down in my armchair. (I must

correct this, for I just

remembered that it was

different: I awoke with an

extremely unpleasant feeling,

but without a definite pain,

but I hurried in spite of it

(!) to my armchair.) I became

continually worse. We called

doctors…I had believed that I

had a heart attack or heart

spasm. But Dr Jones determined

that this was not the case and

gave me an injection of

Dilaudid ‘in order to bring

the patient at ease’. It

worked very quickly. The pain

went away. Then I must have

lost consciousness. For the

last thing that I heard was my

wife saying ‘you take his feet

and I will take his

shoulders’, and apparently

they returned me to the bed. I

do not know how long I was

unconscious. It must have been

several hours, for the first

thing I remember was that a

man with coal-black hair was

bending over me and making

every effort to feed me

something. My wife said (to

keep me from being alarmed!)

‘This is the doctor!’ But I

remember having been

astonished since Dr Jones had

silver-white hair. It was

Gene, the male nurse. An

enormous person, a former

boxer, who could pick me up

and put me down again like a

sofa cushion.

The Trio,

which Schoenberg described to many

people as “a ‘humorous’

representation of my sickness”,

was begun on 20 August, only three

weeks after the episode, and was

completed on 23 September 1946.

The sketches include the writing

and re-writing of the twelve-note

set on which the piece is based.

Schoenberg often started in this

fashion, but atypically there is a

detailed chart, measure by

measure, of the form of the piece.

The Trio contains some of the most

virtuosic string writing in his

entire output, which the composer

recognized by providing various

ossias in all three parts. Thomas

Mann, in his account of the

origins of Doctor Faustus,

reported a conversation with

Schoenberg:

The work was extremely

difficult to play, he said, in

fact almost impossible or at

best only for three players of

virtuoso rank; but, on the

other hand, the music was very

rewarding because of its

extraordinary tonal effects.

The music is

deep enough to bear up to any kind

of listening. It can be heard in

the context of common practice

harmony, as a melodic and textural

essay, or as a story which

describes a near death experience,

an injection to the heart, and

Gene, the male nurse.

Four Pieces for Mixed Chorus,

Op. 27

Schoenberg, who was a master of

all forms of music, excelled at

choral writing. Friede auf

Erden, Gurrelieder,

Moses und Aron, Six

Pieces for Male Choir, as

well as the Four Pieces for

Mixed Chorus, Op. 27, all

point to his genius. The composer

wrote the texts for the first

piece, Unentrinnbar

(Inescapable) and the second, Du

sollst nicht, du musst (You

should not, you must). The texts

for the third, Mond und

Menschen (Moon and Mankind),

by Tschan-Jo-Su, and the fourth,

Der Wunsch des Liebhabers

(The Lover’s Wish), by

Hung-So-Fan, are from Hans

Bethge’s Die chinesiche Flöte (The

Chinese Flute). It is important to

note that the second piece is

often cited as early evidence of

the composer’s plan to return to

Judaism which he finally realized

on 24 July 1933. (He had become a

Protestant on 21 March 1898.) In a

letter to Berg on 16 October 1933,

Schoenberg wrote:

It wasn’t until 1

October that my going to

America became the kind of

certainty I could believe in

myself. Everything that

appeared in the newspapers

both before and since was

founded on fantasy, just as

are the purported ceremonies

and the presence of ‘tout

Paris’ at my so-called return

to the Jewish faith. (tout

Paris was, besides the rabbi

and myself: my wife and a Dr

Marianoff, with whom all these

dreadful tales probably

originated.) As you have

surely observed, my return to

the Jewish faith took place

long ago and is even

discernible in the published

portions of my work (“Du

sollst nicht…du musst…”)

Schoenberg’s

choral music can be understood as

part of the long tradition of

German choral music. Although much

of his music has been labelled as

“modern”, the composer himself

felt that the part-writing in the

first piece “follows in the

tradition of the proven balance of

design and sound. The melody

submits to principles of

simplicity: two series of

canonical forms are intertwined,

the basic form, and its inverse

transposition a fifth lower”.

Throughout his career as a

composer Schoenberg saw himself as

a traditionalist. All of his

harmonic, rhythmic and

orchestrational advances were

necessary in order for him to

create music in his own image.

These two aphorisms by Schoenberg

suggest some of his attitudes

about composition:

1. The man is what he

experiences; the artist

experiences only what he is.

2. My

inclinations developed more

rapidly from the moment that I

started to become clearly

conscious of my aversions.

Three

Satires for Mixed Chorus, Op. 28

The Three Satires for Mixed

Chorus, Op. 28 (1925–26),

present problems for some and

provide joy for others. In a

letter to Amadeo de Filippi, 13

May 1949, Schoenberg stated: “I

wrote them when I was very much

angered by attacks of some of my

younger contemporaries at this

time and I wanted to give them a

warning that it is not good to

attack me”. In the Foreword he

describes the type of composer he

is satirizing:

My targets were all

those who seek their personal

salvation by taking the middle

course. For the middle course

is the only one not leading to

Rome. But it is taken by those

who nibble at dissonances,

wanting to pass for modern but

are too cautious to draw to

the consequences, consequences

resulting not from the

dissonances but also and even

more so, from the consonances.

I aim at

those who pretend to strive back

to…Such a person should not

attempt to make people believe

that it rests with him to decide

how far back he will soon find

himself. Or even intimate that by

this process he is coming one step

closer to one of the great

masters.

I take pleasure in making the

folklorists my target as well, who

apply a technique, which only

suits a complicated way of

thinking, to the naturally

primitive ideas of folk music,

either because they have to (since

they have no themes of their own

at their command) or because they

do not have to (since an existing

musical culture and tradition

could eventually bear them, too).

Finally all…ists in whom I

can see only mannerists. Their

music is enjoyed most by people

who constantly think of the slogan

intended to keep them from

thinking of anything else, while

they are listening to the music.

Schoenberg wrote the texts to the

Satires himself so he was able to

hurl double darts - words and

music - at his attackers. No. 1, Am

Scheideweg (At the

Crossroads), for a cappella

chorus, confronts the

apparent dichotomy between tonal

and atonal music. No. 2, Vielseitigkeit

(Versatility), also for a cappella

chorus, makes fun of “little

Modernsky”, a composer with an

old-fashioned haircut and a

misconception about his own music.

No. 3, Der neue Klassizismus

(The New Classicism) is “A Little

Cantata” for mixed chorus

accompanied by viola, cello and

piano that lampoons a composer who

flirts with different musical

styles and finally decides on a

“pure and perfect” classical

style.

Although Schoenberg expressed his

concern about “the greater danger:

that some of the people at who I

am aiming these Satires might

wonder whether they should

consider themselves my targets”,

on 30 May 1926, Alban Berg wrote

to him:

Oh, how happy your

‘Foreword’ made me, dearest

esteemed friend. You really

have finished off Krenek with

this and with him half—what am

I saying—9/10 of the U.E.

catalogue!

In a telling

statement from 1929, Schoenberg,

when asked to comment on the

current musical situation for the

journal Der Querschnitt,

responded:

I want to hurry

answering this question,

otherwise I shall get there

too late, as happened with the

Satires that I wrote four

years ago about what was then

current: they had scarcely

been printed when they became

obsolete, faster than anything

else by me.

We can only

guess who were Schoenberg’s

attackers, and we do not need to

know. Perhaps today we can strip

away the “programme” and enjoy the

Three Satires as we can the

Bach Cantata No. 201,

The Battle between Phoebus and

Pan, without worrying about

the name of the music critic who

was Bach’s target.

Fred Sherry

Septet-Suite, Op. 29

In its playfulness and sustained

high spirits, the Septet-

Suite, Op. 29 resembles the

Serenade. Five of the seven

instruments—the trio of strings

and two of the clarinets—are

employed in both pieces, and both

embody neoclassic forms and Ländler

styles. A typewritten note

fastened to the sketchbook for the

Suite indicates that, again like

the Serenade, Schoenberg

originally had a work of seven

movements in mind, though from his

description of them only the first

two are recognizable in the

finished four movement piece: “1.

(Movement) 6/8, light, elegant,

gay, bluff. 2. Jojo. Foxtrot.”

Schoenberg began the composition

at the end of October 1924 with a

sketch of bars 5–12 of the first

movement. He then turned to the

second movement, written between 1

January and 19 July 1925, and the

third, which is dated 19 July–15

August 1925. Meanwhile, on 17

June, he resumed work on the first

movement, and, on 17 August,

started on the fourth. Movements

one and four were completed on,

respectively, 1 March 1926 and 15

April 1926. Since the choruses Op.

27 and Op. 28 were composed in the

autumn of 1925, most of the Septet-Suite

is closer in time to them than the

separation by opus numbers

implies. E flat (Es, or S, in

German) and G, the initials of the

composer and his wife, Gertrud,

are the first two notes of the

combinatorial twelve-tone row with

which the Suite is

constructed. The two notes are

also referential pitches

throughout, providing a kind of

tonal bracket for the whole work.

The E flat is sustained in unison

toward the end of the first

movement and in the bass clarinet

alone near the beginning of the

second, both doubtless being

intended as private jokes. The E

flat and G are also the two top

notes of the first chord of the

second movement, Dance the

foxtrot of Schoenberg’s

original title, and the first two

notes of its main theme; they are

also the first two harmonic notes

of the third movement and the

first two melodic notes

(unaccompanied) of the last.

Schoenberg’s biographer, H.H.

Stuckenschmidt, classifies the Ouverture

(first movement) as an example of

sonata-form, with its two themes,

development, reprise and coda, and

it is true that the exposition of

the first section is sonata-like,

as are its recapitulations. But

the three-metre Ländler

episodes, which account for

considerably more than half of the

playing time, suggest that the

title was intended to evoke the

opening movement of an early

eighteenth-century dance suite.

The introduction is defined by

four chords without piano, each

one containing six pitches and

each followed by six piano notes

containing the other six. The

four-chord pattern reappears in

the cello (bars 14–17); viola with

cello (bars 27–29); viola alone

(bars 53–55), and in all three

strings, playing pizzicato at

first (bars 125–127; 133–136),

then arco (bars 137–139 and in the

coda). After the opening chords,

shorter motives lead to the two

principal themes, played by violin

and viola simultaneously.

The fast, jagged section gives way

to a gentle, broader, melodically

sustained one introduced by the

violin alone. A return to the

music of the first tempo follows,

developing the second principal

theme, then a still slower section

with an extended Ländler melody in

the muted viola. The upper

register clarinet repeats the

viola melody an octave higher.

Later the violin plays it in the

home “key” of E flat, in a

development that extensively

exploits harmonics in all three

strings. In the next episode, a

reprise of the first-tempo music,

the clarinets restate the first

principal theme in its original

and inverted forms, while the

strings play triple stop chords

mounting to a climax marked by a

pause. A return to the

broader-tempo melody follows, this

time in the cello, then again the

music of the first tempo and a

final excerpt of the Ländler. In

the coda, the strings play the

first theme in unison and the

movement ends, like the other

three, on the offbeat. The Ouverture

is in 6/8, with 3/4 counter

rhythms one of them identical with

a figure in Liszt’s C minor Transcendental

Etude. (Some conductors

actually beat the 3/4 bars in

three, thereby vitiating the

cross-rhythm that Schoenberg

clearly intended.) The rhythmic

vocabulary is remarkably simple:

dotted figures in the first theme,

then successions of sixteenth

notes (semiquavers) and eighths

(quavers); the piano part is

confined to sixteenths in the

first 24 bars and Morse code-like

syncopation in the first etwas

breiter (broader) section. Triplet

figures occur in only one bar and

not prominently there.

The piano, the principal solo

instrument in the Suite,

though the earliest sketches do

not include it, engages in

dialogues with both the clarinet

and string groups, which alternate

in playing each other’s music.

Twice in the movement the piano

provides transitional interludes

from slower sections back to those

in the first tempo; the second of

them, bridging the Ländler excerpt

and the coda, resembles the one

between Parodie and Mondflec Dance

Steps, like the Ouverture,

alternates sections of fast and

slow music of contrasting

character. In one passage (bars

56–58) the piano accompaniment

recalls the effect, in the slow

movement of Haydn’s Sonata No. 46

in A flat, of making the rhythm

appear twice as fast by steady

syncopation between the left hand

music and the right hand music.

Rapid repeated note figures with

wide leaps on accented offbeats

are a feature of Dance Steps, as

are string harmonics and strings

playing with bouncing bow and by

tapping with the wood of the bow.

The middle register clarinet

exposes the long, easy-to-follow

main theme in both the original

and, without break, reverse

orders.

The third movement, Theme and

Variations, demonstrates that a

tonal-centred melody, Friedrich

Silcher’s popular song, Ännchen

von Tharau, is not incompatible

with atonal twelve-tone music. The

melody is first heard in the bass

clarinet in E major. Since its

third note is the same as its

first, the remaining ten notes of

the chromatic scale are sounded

before the repeated note, a rule

of twelve-tone composition at the

time (1925). Accordingly, the ten

notes are comprised in the piano

accompaniment to the first two

bass clarinet notes. The same

method is employed throughout the

movement. At the beginning the

harmony consists entirely of

sixths and thirds, the piano

forming one of each of these by

combining with the two bass

clarinet notes. Each of the

variations Allegro molto, mässige,

Langsam, Moderato is radically

different in character, the range

of contrasts greater than in the

other movements. In Variation 1,

the piano interjects sprinklings

of loud notes between groups of

fast-tempo figures in strings and

clarinets alternating and playing

softly. Variation 2 is a piano

solo, Variation 3 a solo by the

high register clarinet accompanied

by 128th notes at the top of the

piano register, together with

still higher violin harmonics.

Variation 4, a 6/8 Bach dance,

leads to the coda, the first part

of which, in the same tempo as the

beginning, recapitulates the

Ännchen melody in the lower

register of the piano. In the fast

3/4 second part each clarinet

plays a single explosive note in a

rotation that sounds the rhythm in

every bar.

The subject of the fugal Gigue,

played first by the middle

register clarinet, exposes the

twelve pitches of the principal

theme of the first movement, but

in equal note values. The bass

clarinet responds, playing the

inversion of the same notes in

counterpoint to the continuing

middle register clarinet, followed

by the high register clarinet

restating the opening form of the

subject an octave higher. The

middle register clarinet also

introduces the second theme,

Ländler in character, which is

broken into phrases with rests

between. The four-beat pulsation

gives way to six beats and the

polyphonic first part of the

movement to block harmonies; from

here to the end, the two rhythms

and styles alternate and combine.

The first half of the movement

concludes startlingly, in a C

sharp major triad. The more

densely contrapuntal second half

employs the inversion of the

interval of the first half. The

slow section that precedes the

ending consists of a long-line

melody in the violin, returning,

in the cello, to the Ännchen song

of the third movement, and a

stratospheric conversation between

the piano and the high register

clarinet, each speaking in

six-note phrases.

The standard study of the

Septet-Suite is Martha Hyde’s

Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Harmony:

The Suite Op. 29 and the

Compositional Sketches, University

of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor,

1981. The listener seeking to

understand the “harmonic problem”,

which, Ms Hyde concedes, “has been

and remains the major problem in

both the theory and the practice

of twelve-note composition”,

should consult her book. Its title

is misleading in that she analyzes

only the first movement, on

grounds that the sketch material

for it is more extensive than that

for the other three. She explains

that Schoenberg characteristically

“worked out certain harmonic

structures or designs that he used

again in varied forms throughout

the composition” (which does not

accord with the chronology of the

composition). Ms Hyde remarks,

perceptively, that the sketches

“reflect a self-consciousness

often not apparent” in

Schoenberg’s later works. But her

most interesting chapter is

devoted to the theory of

correspondence between metre and

harmony in the piece.

In a copy of the manuscript which

was consulted for the recording,

Fred Sherry pointed out a nota

bene, in what appears to be the

composer’s handwriting, underneath

bar 129 in the fourth movement. It

reads: “NB die Arpeggien ohne

rit.” which suggested to the

present performers that while the

music is in “molto rit.” the

crossing strings figures in the

violin, viola and cello are to be

played in tempo. The recorded

performance of the première, which

Schoenberg conducted on 15

December 1927, makes a slight

accelerando starting in bar 129,

leading the listener to believe

that the connection between the

slow music and the faster coda was

of greatest importance to the

composer.

Accompaniment to a

Cinematographic Scene, Op. 34

Schoenberg began to compose his

Accompaniment to a Cinematographic

Scene, Op. 34, music for an

imaginary film, on 15 October

1929, and finished it on 14

February 1930. The first

performance, on 28 April 1930, was

by the Frankfurt Radio Orchestra,

conducted by Hans Rosbaud. It

might be said that the classical

dramatic formula of the subtitle

provided the composer with the

perfect vehicle for his

“expressionist” style. The

structure is the easiest to hear

and follow of any of his pieces

employing twelve-tone technique,

partly because the nine episodes

leading to the Catastrophe are

delineated by successively faster

tempos and/or rhythmic units. At

the Catastrophe the pulsation

slows to the same tempo as the

beginning which is not the only

symmetry in the construction of

the piece. In the first and last

segments, the tonality of E flat

minor is sustained throughout in

the lower strings, and E flat is

the emphasized referential pitch

in the middle as well, most

prominently at the climax (mm.

144–152), first in the bass

instruments, then repeated four

octaves higher in the violins.

Robert Craft

|

|