|

|

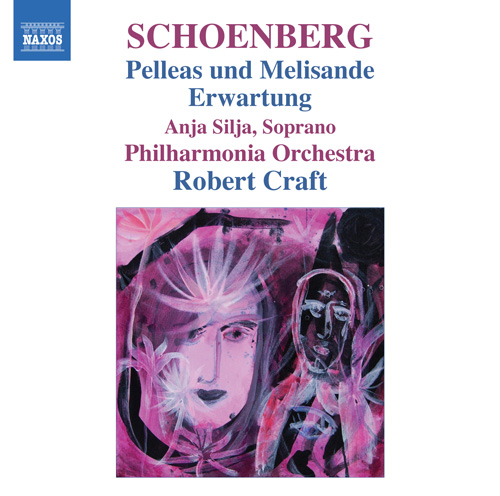

1 CD -

8-557527 - (c) 2008

|

|

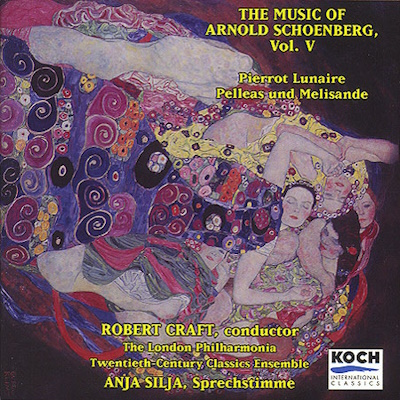

1 CD -

3-7471-2 - (p) 2000 *

|

|

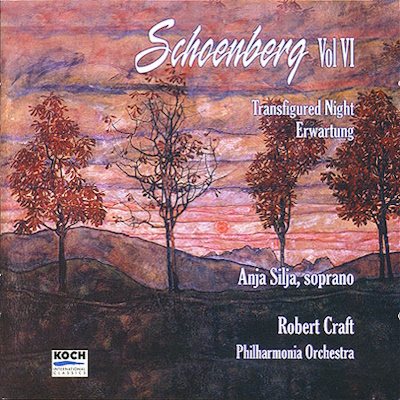

| 1 CD -

3-7473-2 - (p) 2000 ** |

|

| THE ROBERT

CRAFT COLLECTION - The Music of Arnold

Schoenberg - Volume 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arnold

SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) |

Pelleas

und Melisande (1902)

|

*

|

|

40' 23"

|

|

|

-

Beginning

|

|

6' 41" |

|

1 |

|

-

Lebhaft

|

|

4' 00" |

|

2 |

|

-

Sehr rasch

|

|

1' 52" |

|

3 |

|

-

Rehearsal 23

|

|

6' 52" |

|

4 |

|

-

Langsam

|

|

7' 41" |

|

5 |

|

-

Sehr langsam

|

|

5' 45" |

|

6 |

|

-

Sehr langsam |

|

7' 33" |

|

7 |

|

Erwartung,

Op. 17 (1909) |

** |

|

28' 36" |

|

|

-

Scene 1

|

|

2' 56" |

|

8 |

|

-

Scene 2

|

|

2' 45" |

|

9 |

|

-

Scene 3

|

|

2' 23" |

|

10 |

|

-

Scene 4

|

|

20' 32" |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

Anja Silja, Soprano

**

|

PHILHARMONIA

ORCHESTRA

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England):

- 20 August 1999 (Pelleas und

Melisande)

- 16 to 18 February 2000 (Op. 17)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory K.

Squires

|

|

|

Editor |

|

Richard

Price

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Michael

Sheedy

|

|

|

Assistant

engineer

|

|

Chris

Clark

|

|

|

Technical

engineer

|

|

Mark

Rogers (Pelleas und Melisande)

Mark Brown (Op. 17)

|

|

|

Digital editing |

|

Wayne

Hileman

|

|

|

NAXOS Edition |

|

Naxos

- 8.557527 | (1 CD) | LC 05537 |

durata 68' 59" | (c) 2008 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH previously

released |

|

KOCH

International Classics | 3-7471-2

| (1 Cd) | LC 06644 | (p) 2000 |

DDD | (Pelleas und Melisande)

KOCH

International Classics |

3-7473-2 | (1 Cd) | LC 06644 |

(p) 2000 | DDD | (Op. 17)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Black

Rose by Ultich Osterloh

(courtesy of the artist)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Schoenberg’s

polyphonic tone poem Pelleas

und Melisande is often

compared to Debussy’s opera based

on the same text by Maurice

Maeterlinck. According to the

composer, “The first performance,

1905, in Vienna, under my own

direction, provoked riots among

the audience and even the critics.

Reviews were unusually violent and

one of the critics suggested

putting me in an asylum and

keeping music paper out of my

reach. Only six years later, under

Oscar Fried’s direction, it became

a great success, and since that

time has not caused the anger of

the audience”. The most innovative

features of Erwartung, a

“monodrama for soprano and large

orchestra”, are the continual

variation of orchestral textures,

and the constantly changing tempi.

Not only are the instrumental

combinations new, but the

instruments themselves are

required to produce new sounds.

Pelleas und Melisande

Schoenberg began the composition

of his polyphonic tone poem Pelleas

und Melisande in Berlin in

1902 and completed it in Vienna

the following year. According to

the composer, “The first

performance, 1905, in Vienna,

under my own direction, provoked

riots among the audience and even

the critics. Reviews were

unusually violent and one of the

critics suggested putting me in an

asylum and keeping music paper out

of my reach. Only six years later,

under Oscar Fried’s direction, it

became a great success, and since

that time has not caused the anger

of the audience”. However, the

piece was highly praised when

performed in Prague in February

1912, in Amsterdam in November,

and in St Petersburg in December.

Stravinsky, who had just met the

Viennese composer in Berlin, wrote

to musician friends in his native

city extolling the genius of

Schoenberg, though he himself had

not yet heard Pelleas und

Melisande.

The music is often compared to

Debussy’s opera based on the same

text by Maurice Maeterlinck, and

the distinction has been widely

accepted that Schoenberg succeeded

in elevating the same material

from the particular to the

general. Thus he does not attempt

to evoke the sounds and atmosphere

of the first scene in the forest

in Brittany, in which Golaud and

his future wife, Melisande, find

each other, but instead mixes

motives in sombre harmonies and

instrumental colours that

unmistakably convey a sense of

tragic fate. The deep bass

register and the dense harmony at

the beginning are followed by a

solo oboe playing a tender theme

beginning on a high note and

characterizing Melisande. This

theme is developed polyphonically,

as are all of the other themes.

Neither before nor since has any

music for large orchestra offered

so many layers of intertwined

counterpoint. The scene in the

death chamber of Melisande

coincidentally employs the

whole-tone scale for the first

time in the world of German music,

whether or not Schoenberg borrowed

it from Debussy. This most

gorgeous quiet climax in the work

is made beatific by the funereal

brass-instrument chorale in the

middle and lower ranges of the

orchestra.

Erwartung (Expectation)

Monodrama for Soprano and

Large Orchestra

The text of Erwartung, by

Marie Pappenheim, is the interior

monologue of a woman who has

killed the lover with whom,

nevertheless, she is expecting a

tryst. The action, perhaps

dreamed, or composed on a

psychiatrist’s couch, takes place

between twilight and dawn near and

in a forest. It consists of her

search for him, the discovery of

his still-bleeding corpse, and

finally her realisation that

“light will dawn for all others,

but I am all alone in my

darkness”, a line set to the only

tonal music in the work (borrowed

from one of Schoenberg’s early

songs). At the end of the first of

the four scenes, the Woman

overcomes her fears and enters the

forest on a path. Two sharp

timpani notes demarcate the

beginning of the almost equally

short second scene, in which she

feels lost at first, then

remembers that her lover had been

in the same place, the first clue

to her guilt as his murderess. The

second clue is her mistaking a

tree stump for a body. In the

still shorter third scene she

reveals that something black is

dancing in the moonlight,

wondering if it is her lover’s

body—the third clue—but quickly

deciding that it is only a shadow.

The musical tension increases from

quiet agitation to a peak of

orchestral volume, during which

she calls hysterically for her

lover’s help. The scene changes

again during an ostinato, one of

the most prominent in the opus,

partly because the Woman is

offstage and silent, her only

significant rest in the entire

work. The speed of the ostinato

increases, then decreases,

suggesting the chugging of a train

as it approaches and recedes. It

is constructed by the repetition

of a whole-step figure at

different pitches simultaneously,

and in the same even-note rhythm,

of the five string sections, and

by the bassoons repeating a

dotted-note minor-third figure,

and the flutes an eleven-note

figure in octaves in A minor. The

principal motive, in a piercingly

high register, octave-doubled,

suggesting the screech of a night

bird, surmounts this orchestral

accompaniment.

At the beginning of Scene Four,

the Woman emerges onto a road,

from which, in the background, a

house with a balcony becomes

visible in the moonlight. The

music is quiet and virtually

motionless, a chord sustained by

seven instruments, the vocal part

imitating the Woman’s weary

trudging. As she remarks on the

“empty, bloodless moon and

cloudless sky”, a motive in

octaves, bassoon and

contra-bassoon, a hauntingly

hollow sound, introduces an

ostinato—tone-painting of

exquisite subtlety, formed by

bandying five-note chords played

in harmonics by combinations of

solo strings, and by a muted

violin and celesta alternately

playing a quintuplet figure.

The Woman sees a bench and a man’s

body lying on the ground next to

it, glazed eyes staring

lifelessly, blood dripping from a

chest wound. She touches the face,

hair, mouth, and, placing one of

its cold hands on her breast,

recognizes the corpse as her

lover’s. In the

“stream-of-consciousness” text

that follows from here to the end

we learn that the lover had

promised to meet her here tonight,

but he has been less attentive of

late, has not visited her at all

in the last three days, but may

have been seeing another woman,

whose “white arms” the Woman

imagines having seen extended

toward him from the balcony of a

house near the edge of the forest.

Again and again she speaks of the

depths of her love for him,

begging him to “Wake up, wake up.

I love you so”, but these

expressions of tenderness and

fervid passion are mixed with

reproaches. Why, she wonders, have

“they” killed him?, though it is

already clear, since she has

returned magnetically to the scene

of the crime, that she herself, in

a fit of jealousy, is the

murderess. The music confirms that

jealousy was the motive simply by

octave-doubling the melody of her

phrase, “die Frau mit den

weissen Armen”, in the

orchestra, which makes it stand

out more than any other passage in

the remainder of the piece (though

octaves are by no means rare

within the orchestra).

Dawn breaks at the end, and the

nightmare, as Schoenberg called

it, dissolves in a single,

miraculous bar of music. After the

Woman’s last words, “Oh, are you

there?” (shrieked out over the

full orchestra in her minor-third

leitmotiv), followed by

“I’m waiting” (quietly sung in an

ambiguous diminished fifth over

the pianissimo orchestra, which

then evaporates). This ending is

produced by chromatic scales

upward in the higher woodwinds

(fluttertonguing) and strings,

playing in different rhythms,

articulations, and sonorities

(muted violas and cellos,

ponticello, tremolando). Balancing

the ascent, the lower brass,

trombones and tuba (muted and

fluttertonguing) play downward

chromatic scales, while the middle

and upper brass, horns and

trumpets (also muted and

fluttertonguing) provide a

stationary element, entering only

in the latter half of the bar, and

in the middle register, which by

this time has been vacated. The

leading orchestral line is that of

the contrabasses (and

contrabassoon), which also enter

on the second half of the bar, and

in distinction from all the other

instruments, play a descending

whole-tone scale pizzicato, which

increases its distinctness.

Further, the notation - doublets,

triplets, sextuplets, double

sextuplets, and a 48-note

four-octave upward glissando in

the celesta - increases in speed

by subdivision throughout the bar,

whereas the tempo (pulsation)

remains steady. The progressively

higher and lower lines extending

the pitch spectrum from the

beginning of a single note that

begins the piece to the highest

and lowest notes heard at the very

end create the effect of

broadening the musical space. The

change of colour with each

subdivision of the beat is complex

beyond human aural analysis, but

might be compared in the visual

sense to a dense flurry of

confetti.

The most innovative features of

Erwartung are the continual

variation of orchestral textures,

and the constantly changing tempi.

Not only are the instrumental

combinations new, but the

instruments themselves are

required to produce new sounds.

The string players tap with the

wood of their bows, play on or

near the bridge, and perform novel

glissandos (the cellos begin one

of them on a high harmonic and

slide rapidly down the length of

their D strings). All of the wind

instruments fluttertongue and

explore registral extremes (the

bassoon’s sustained high D sharp

at [81] – [88]). The harpist

inserts tissue paper between the

strings at one point, and near the

end of the piece is asked to play

“where possible” a three-note

ostinato figure an octave lower

than where written. The percussion

section is small and sparingly

used, but contributes new effects,

one of them by scraping the rim of

a cymbal with the bow of a string

bass.

The orchestra evokes sounds of

nature - the rustling of the

forest, the noises of its denizens

(a celesta figure suggests a

cricket’s mating song to the

Woman) - but the creation of

atmosphere, moonlit shadows and

such, is less important than the

role of the instruments in

expressing the Woman’s emotions,

her anxieties, yearnings,

desperations, morbid fear and

hatred of her rival, “white arms,”

and especially her always

trancelike mental state. It might

be noted that Schoenberg borrows

her cry for help, high B to low C

sharp, from Kundry’s music in

Parsifal.

The formal structure of Erwartung

depends on the use of ostinati -

repeated figures and sustained

“pedal” notes - and melodic

motives. Not many of the latter

are repeated, but one of them,

identified as much by rhythm as by

intervallic structure, is

especially memorable. It consists

of three notes, a longer first and

third, usually at the same pitch,

with the second a small interval

apart, primarily a minor-second,

above or below. The motive is

heard more frequently at B flat –

A – B flat than at other pitches,

but, lacking a tonal context,

without conveying any tonality.

Since it is heard at the final

climax of the piece, where, to

make the rhythm clearer in the

high register of the violins

intoning it, Schoenberg extends

the interval to and from the

second note to a minor third, it

seems to take precedence as the

Woman’s leitmotif. He increases

its menacing character by

converting the middle note to an

upper minor second and giving it

an upper appoggiatura. This is

most prominent at bars 101, 112,

352, and 375 (without

appoggiatura). The same motive, in

other guises, is recognizable in

the first three notes of the vocal

part; in the tonal (A sharp) flute

melody in bar 9; in the flute and

horn in bars 12–13 (in which the

second note is longer than its

neighbours). It should also be

mentioned that a falling

minor-third, most conspicuously C

sharp – A sharp, is associated

with the Woman from the beginning.

It appears in the oboe melody in

the first full bar of the piece,

but becomes an identifying device

in the vocal part in bar 10, where

the Woman’s phrase concludes with

it, and in bars 19, 23, 28, 38–39,

47–48, as well as in the first

words of Scene Two, where many of

her phrases begin with it. The

same interval is emphasized

countless times later in the

piece.

As for the almost constantly

changing tempi, it must be noted

that in a work of only 427 bars,

the metronome markings shift 111

times, and that between times

instructions are given for more

than eighty additional tempo

controls, fermatas, ritenuti,

accelerandi, etwas

drängend, etwas

beschleunigen, etwas

zurückhaltend, etc. Rarely

does the beat remain constant for

more than a few bars and, at

times, different metronomic

numbers are assigned to several

bars in succession. Still more

fluctuations of tempo are

indicated within the speed of the

orchestra as a whole. Near the

beginning of the fourth scene, for

example, a fast figure that moves

from woodwinds to strings to brass

must be played still faster than

the general beat of the orchestra

(i.e. out of tempo), and at

another place in the same scene

each bass player is required to

play pizzicato at his own

fastest-possible individual speed

(i.e., not together). Obviously no

recorded, and probably no

unrecorded, performance, has as

yet realised most of these tempo

nuances.

Incredibly, the present recording

is the first to include the viola

solo at bars 252–253. It is not

found in any set of the orchestra

parts, an error going back to

1924.

Robert Craft

|

|